Fairchild v Glenhaven Funeral Services Ltd

| Fairchild v Glenhaven Funeral Services Ltd | |

|---|---|

| |

| Court | House of Lords |

| Full case name | Fairchild v Glenhaven Funeral Services Ltd (t/a GH Dovener & Son); Pendleton v Stone & Webster Engineering Ltd; Dyson v Leeds City Council (No.2); Matthews v Associated Portland Cement Manufacturers (1978) Ltd; Fox v Spousal (Midlands) Ltd; Babcock International Ltd v National Grid Co Plc; Matthews v British Uralite Plc |

| Decided | 20 June 2002 |

| Citation(s) | [2002] UKHL 22, [2003] 1 AC 32, [2002] 3 WLR 89, [2002] 3 All ER 305, [2002] ICR 798, [2002] IRLR 533 |

| Court membership | |

| Judge(s) sitting | Lord Bingham of Cornhill; Lord Nicholls of Birkenhead; Lord Hoffmann; Lord Hutton; Lord Rodger of Earlsferry |

| Keywords | |

| Causation, employer liability, material increase in risk | |

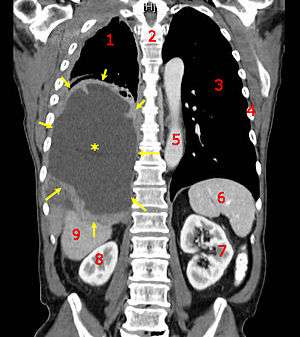

Fairchild v Glenhaven Funeral Services Ltd [2002] UKHL 22 is a leading case on causation in English tort law. It concerned malignant mesothelioma, a deadly disease caused by breathing asbestos fibres. The House of Lords approved the test of "materially increasing risk" of harm, as a deviation in some circumstances from the ordinary "balance of probabilities" test under the "but for" standard.

Facts

Mr Fairchild had worked for a number of different employers, as a subcontractor for Leeds City Council, all of whom had negligently exposed him to asbestos. Mr Fairchild contracted pleural mesothelioma. He died, and his wife was suing the employers on his behalf for negligence. A number of other claimants were in similar situations, and joined in on the appeal. The problem was, a single asbestos fibre, inhaled at any time, can trigger mesothelioma. The risk of contracting an asbestos related disease increases depending on the amount of exposure to it. However, because of long latency periods (it takes 25 to 50 years before symptoms of disease become evident) it is impossible to know when the crucial moment was. It was impossible therefore for Mr Fairchild to point to any single employer and say "it was him". Moreover, because the traditional test of causation is to show that "on the balance of probabilities" X has caused Y harm, it was impossible to say that any single employer was the cause at all. While it was possible to say "it was one of them" it was impossible to say which. Under the normal causation test, none of them would be found, on the balance of probabilities to have caused the harm.

Judgment

The House of Lords held that, following McGhee v National Coal Board[1] the appropriate test in this situation, was whether the defendant had materially increased the risk of harm toward the plaintiff. The employers were joint and severally liable against the plaintiff (though amongst themselves they could sue one another for different contributions).

Lord Bingham, in particular, noted that in this case it was not possible to speak of "probabilities" in a simple way, because,

"It is on this rock of uncertainty, reflecting the point to which medical science has so far advanced, that the three claims were rejected by the Court of Appeal and by two of the three trial judges."[2]

Moreover,

"The overall object of tort law is to define cases in which the law may justly hold one party liable to compensate another."[3]

It was wrong to deny the claimants any remedy at all. Therefore, the appropriate test of causation is whether the employers had materially increased the risk of harm to the claimants.

Significance

The cost of this ruling was enormous. It is estimated that this single judgment was worth £6.8bn. Approximately 13 Britons die every day from asbestos related diseases, and the rate of deaths are increasing.

In this context, another asbestos related case came before the House of Lords in Barker v Corus [2006] UKHL 20. This time the question was whether, if one of the employers that was responsible for the materially increasing the risk of harm had gone insolvent, should the solvent employers pick up the proportion for which that insolvent employer was responsible? The House of Lords accepted the argument that the solvent employer should not. So for example, Mr B has worked for employers X, Y, and Z for ten years each. X, Y and Z have all exposed Mr B to asbestos, and it is not possible to say with which employer Mr B had contracted a disease. But now X and Y have gone insolvent, and Mr B is suing Z. The House of Lords held that Z would only have to pay one third of the full compensation for Mr B's disease, in other words, Z has only "proportionate liability" for that part which he materially increased the risk of Mr B's harm. This outcome was advocated by a number of academics.[4]

The essential decision to be made is whether a tortfeasor or a claimant should bear the risk of other tortfeasors going insolvent. It is important to keep in mind, that in the example above, Z may not have actually caused any harm. Moreover, it might have been that Z in fact caused all the harm. After the decision in Barker there was a swift and fierce political backlash, with large numbers of workers, families, trade unions, and Members of Parliament calling for the reversal of the ruling. This was on the basis that it would undermine full compensation for working people and their families. Soon enough the Compensation Act 2006[5] was introduced, specifically to reverse the ruling. However the Act only applies to mesothelioma. What remains to be seen is whether the "proportionate liability" idea will crop up in other situations.

See also

- Barker v. Corus

- Asbestos and the law

- Negligence

- English tort law

- Causation

- McGhee v National Coal Board

- Legislation cited

- Factories Act 1961 (c 34) ss 63 and 155

Notes

External links

- Full judgment from the House of Lords.