Far-sightedness

| Far-sightedness | |

|---|---|

| hypermetropia, hyperopia, longsightedness[1] | |

|

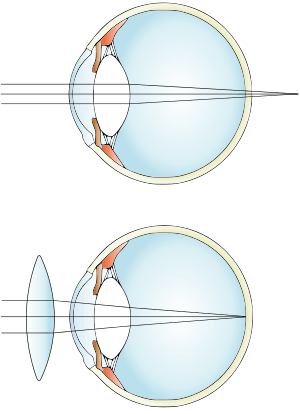

Far-sightedness lens correction | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | Ophthalmology |

| ICD-10 | H52.0 |

| ICD-9-CM | 367.0 |

| DiseasesDB | 29644 |

| MedlinePlus | 001020 |

| MeSH | D006956 |

Far-sightedness, also known as hyperopia, is a condition of the eye in which light is focused behind, instead of on, the retina.[2] This causes close objects to be blurry, while far objects may appear normal.[2] As the condition worsens, objects at all distances may be blurred.[2] Other symptoms may include headaches and eye strain.[2] People with hyperopia can also experience accommodative dysfunction, binocular dysfunction, amblyopia, and strabismus,[3]

The cause is an imperfection in the eye: often when the eyeball is too short, or the lens cannot become round enough.[4] It is a type of refractive error.[2]

Correction is usually achieved by the use of convex corrective lenses. For near objects, the eye has to accommodate even more. Depending on the degree of hyperopia and the age of the person, which directly relates to the eye's accommodative ability, the symptoms can be different.[1]

Far-sightedness primarily affects young children, with rates of 8% at 6 years and 1% at 15 years.[5]

Signs and symptoms

The signs and symptoms of far-sightedness are blurry vision, headaches, and eye strain.[4] The common symptom is eye strain. Difficulty seeing with both eyes (binocular vision) may occur, as well as difficulty with depth perception.[1]

Causes

As hyperopia is the result of the visual image being focused behind the retina, it has two main causes:[4]

- Low converging power of eye lens because of weak action of ciliary muscles

- Abnormal shape of the cornea

Far-sightedness is often present from birth, but children have a very flexible eye lens, which helps make up for the problem.[6] In rare instances hyperopia can be due to diabetes, and problems with the blood vessels in the retina.[1]

Diagnosis

A diagnosis of farsightedness can be made via a slit-lamp test which examines the cornea, conjunctiva, and iris.[7][8]

In severe cases of hyperopia from birth, the brain has difficulty in merging the images that each individual eye sees. This is because the images the brain receives from each eye are always blurred. A child with severe hyperopia can never see objects in detail. If the brain never learns to see objects in detail, then there is a high chance of one eye becoming dominant. The result is that the brain will block the impulses of the non-dominant eye. In contrast, the child with myopia can see objects close to the eye in detail and does learn at an early age to see detail in objects.

Classification

Hyperopia is typically classified according to clinical appearance, its severity, or how it relates to the eye's accommodative status.[3]

- Simple hyperopia

- Pathological hyperopia

- Functional hyperopia

Other common types of refractive errors are near-sightedness, astigmatism, and presbyopia.[2]

Treatment

Treatment of far-sightedness includes the use of contact lenses and eyeglasses.[9][10] Other treatments are:

- PRK: the removal of a minimal amount of the corneal surface[11][12]

- LASIK: laser eye surgery to reshape the cornea, so that glasses or contact lenses are no longer needed.[12][13]

- Refractive Lens Exchange: a variation of cataract surgery; the difference is the existence of abnormal ocular anatomy which causes a high refractive error.[14]

- LASEK: resembles PRK, but uses alcohol to loosen the corneal surface.[11]

Complications

Farsightedness can have rare complications such as strabismus and amblyopia. At a young age, severe farsightedness can cause the child to have double vision as a result of "over-focusing".[15]

References

- 1 2 3 4 "Long Sight - Hypermetropia. Causes of longsightedness | Patient". Patient. Retrieved 2016-02-26.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Facts About Refractive Errors". NEI. October 2010. Retrieved 30 July 2016.

- 1 2 American Optometric Association. Optometric Clinic ef_error_pres.htm "Refractive Error and Presbyopia." Refractive Source.com Accessed September 20, 2006.

- 1 2 3 "Facts About Hyperopia | National Eye Institute". nei.nih.gov. Retrieved 2016-02-26.

- ↑ Castagno, VD; Fassa, AG; Carret, ML; Vilela, MA; Meucci, RD (23 December 2014). "Hyperopia: a meta-analysis of prevalence and a review of associated factors among school-aged children.". BMC ophthalmology. 14: 163. PMID 25539893.

- ↑ "Normal, nearsightedness, and farsightedness: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia Image". www.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2016-02-26.

- ↑ "Farsightedness: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". www.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2016-02-26.

- ↑ "Slit-lamp exam: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". www.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2016-02-26.

- ↑ Chou, Roger; Dana, Tracy; Bougatsos, Christina (2011-02-01). "Introduction". PubMed Health.

- ↑ Information, National Center for Biotechnology; Pike, U. S. National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville; MD, Bethesda; Usa, 20894. "Farsightedness (Hyperopia): Treatments - National Library of Medicine". PubMed Health. Retrieved 2016-02-26.

- 1 2 Choices, NHS. "Long-sightedness - Treatment - NHS Choices". www.nhs.uk. Retrieved 2016-02-26.

- 1 2 Settas, George; Settas, Clare; Minos, Evangelos; Yeung, Ian Yl (2012-01-01). "Photorefractive keratectomy (PRK) versus laser assisted in situ keratomileusis (LASIK) for hyperopia correction". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 6: CD007112. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007112.pub3. ISSN 1469-493X. PMID 22696365.

- ↑ "Laser Eye Surgery: MedlinePlus". www.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2016-02-26.

- ↑ Alió, Jorge L; Grzybowski, Andrzej; Romaniuk, Dorota (2014-12-10). "Refractive lens exchange in modern practice: when and when not to do it?". Eye and Vision. 1. doi:10.1186/s40662-014-0010-2. ISSN 2326-0254. PMC 4655463

. PMID 26605356.

. PMID 26605356. - ↑ Choices, NHS. "Long-sightedness - Complications - NHS Choices". www.nhs.uk. Retrieved 2016-02-26.

Further reading

- Kulp, Marjean Taylor; Ying, Gui-shuang; Huang, Jiayan; Maguire, Maureen; Quinn, Graham; Ciner, Elise B.; Cyert, Lynn A.; Orel-Bixler, Deborah A.; Moore, Bruce D. (2014-04-01). "Associations between Hyperopia and other Vision and Refractive Error Characteristics". Optometry and vision science: official publication of the American Academy of Optometry. 91 (4): 383–389. doi:10.1097/OPX.0000000000000223. ISSN 1040-5488. PMC 4051821

. PMID 24637486.

. PMID 24637486. - Wilson, Edward M.; Saunders, Richard; Rupal, Trivedi (2008-11-14). Pediatric Ophthalmology: Current Thought and A Practical Guide. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9783540686323.

External links

- "National Institutes of Health releases data from largest pediatric eye study | National Eye Institute". nei.nih.gov. Retrieved 2016-02-26.