Foreskin

| Foreskin | |

|---|---|

|

Foreskin partially retracted over the glans penis, with a ridged band visible at the end of the foreskin | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | Genital tubercle, urogenital folds |

| Artery | Dorsal artery of the penis |

| Vein | Dorsal veins of the penis |

| Nerve | Dorsal nerve of the penis |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Praeputium |

| MeSH | A05.360.444.492.362 |

| TA | A09.4.01.011 |

| FMA | 19639 |

In male human anatomy, the foreskin is a double-layered fold of smooth muscle tissue, blood vessels, neurons, skin, and mucous membrane that covers and protects the glans penis and the urinary meatus. It is also described as the prepuce, a technically broader term that also includes the clitoral hood in women, to which the foreskin is embryonically homologous. The highly innervated mucocutaneous zone of the penis occurs near the tip of the foreskin. The foreskin is mobile, fairly stretchable, and acts as a natural lubricant.

The foreskin of adults is typically retractable over the glans. Coverage of the glans in a flaccid and erect state varies depending on foreskin length. The foreskin is attached to the glans at birth and is generally not retractable in infancy.[1] The age at which a boy can retract his foreskin varies, but research found that 95% of males were able to fully retract their foreskin by adulthood.[2] Inability to retract the foreskin in childhood should not be considered a problem unless there are other symptoms.[3]

The World Health Organization debates the precise functions of the foreskin, which may include "keeping the glans moist, protecting the developing penis in utero, or enhancing sexual pleasure due to the presence of nerve receptors".[4]

The foreskin may become subject to a number of pathological conditions.[5] Most conditions are rare, and easily treated. In some cases, particularly with chronic conditions, treatment may include circumcision, a procedure where the foreskin is partially or completely removed.

Description

The outside of the foreskin is a continuation of the skin on the shaft of the penis, but the inner foreskin is a mucous membrane like the inside of the eyelid or the mouth. The mucocutaneous zone occurs where the outer and inner foreskin meet. The ridged band of highly innervated tissue is located just inside the tip of the foreskin. Like the eyelid, the foreskin is free to move after it separates from the glans, which usually occurs before or during puberty. The foreskin is attached to the glans by a frenulum.

Taylor et al. (1996) reported the presence of Krause end-bulbs and a type of nerve ending called Meissner's corpuscles.[6] Their density is reportedly greater in the ridged band (a region of ridged mucosa at the tip of the foreskin) than in the larger area of smooth mucosa.[6] They are affected by age: their incidence decreases after adolescence.[7] Meissner's corpuscles could not be identified in all individuals.[8] Bhat et al studied Meissner's corpuscles at a number of different sites, including the "finger tips, palm, front of forearm, sole, lips, prepuce of penis, dorsum of hand and dorsum of foot". They found the lowest Meissner's Index (density) in the foreskin, and also reported that corpuscles at this site were physically smaller. Differences in shape were also noted. They concluded that these characteristics were found in "less sensitive areas of the body".[9] In the late 1950s, Winkelmann suggested that some receptors had been wrongly identified as Meissner's corpuscles.[10][11]

The College of Physicians and Surgeons of British Columbia has written that the foreskin is "composed of an outer skin and an inner mucosa that is rich in specialized sensory nerve endings and erogenous tissue."[12]

Development

Eight weeks after fertilization, the foreskin begins to grow over the head of the penis, covering it completely by 16 weeks. At this stage, the foreskin and glans share an epithelium (mucous layer) that fuses the two together. It remains this way until the foreskin separates from the glans.[13]

According to a 1949 study by Gairdner, the foreskin is usually still fused with the glans at birth.[13] As childhood progresses, they gradually separate.[14] There are differing reports on the age at which the foreskin can be retracted. Thorvaldsen and Meyhoff (2005) reported that 21% of 7-year-old boys in their study had non-retractable foreskins and this proportion dropped to 7% at puberty, with first retraction at an average age of 10.4 years[15] but Gairdner (1949) reported that only 10% of 3-year-old boys had non-retractable foreskins,[13] however, Gairdner was wrong about development of foreskin retraction.[1][16] Wright (1994) argues that forcible retraction of the foreskin should be avoided and that the child himself should be the first one to retract his own foreskin.[1] Attempts to forcibly retract it can be painful and may cause injury.[17]

In children, the foreskin usually covers the glans completely but in adults it may not. Schöberlein (1966) conducted a study of 3,000 young men from Germany and found that 49.6% had the glans fully covered by foreskin, 41.9% were partially covered and 8.5% were uncovered - around half of which (4%) had the foreskin atrophied spontaneously without previous surgery.[18] During erection, the degree of automatic foreskin retraction varies considerably; in some adults, the foreskin remains covering all or some of the glans until retracted manually or by sexual activity. This variation was regarded by Chengzu (2011) as an abnormal condition named 'prepuce redundant'. Frequent retraction and washing under the foreskin is suggested for all adults but particularly for those with a long, or 'redundant' foreskin.[19] When the foreskin is longer than the erect penis, it will not spontaneously retract upon erection.

It is shown that manual foreskin retraction during childhood or even adulthood serves as a stimulant to normal development and automatic retraction of the foreskin, which suggests that many conditions affecting the foreskin may be prevented or cured behaviorally.[20] Some males, according to Xianze (2012), may be reluctant for their glans to be exposed because of discomfort when it chafes against clothing, although the discomfort on the glans was reported to diminish within one week of continuous exposure.[21] Guochang (2010) states that for those whose foreskins are too tight to retract or have some adhesions, forcible retraction should be avoided since it may cause injury.[22]

Functions

The World Health Organization state that there is "debate about the role of the foreskin, with possible functions including keeping the glans moist, protecting the developing penis in utero, or enhancing sexual pleasure due to the presence of nerve receptors".[23] The foreskin helps provide sufficient skin during an erection.[24] The Nordic Association of Clinical Sexology states that the foreskin "contributes to the natural functioning of the penis during sexual activity."[25]

Sexual

The foreskin is specialised tissue that is packed with nerves and contains stretch receptors.[6][26][27] Sorrells et al. (2007) reported the areas of the penis most sensitive to fine touch are on the foreskin.[28]

The foreskin enables the penis to slip in and out of the vagina non-abrasively inside its own sheath of self lubricating, movable skin.[29]

Taylor et al. (1996) described the foreskin in detail, documenting a ridged band of mucosal tissue. They stated: "This ridged band contains more Meissner's corpuscles than does the smooth mucosa and exhibits features of specialized sensory mucosa."[6] In 1999, Cold and Taylor stated: "The prepuce is primary, erogenous tissue necessary for normal sexual function."[26] Boyle et al. (2002) state that "the complex innervation of the foreskin and frenulum has been well documented, and the genitally intact male has thousands of fine touch receptors and other highly erogenous nerve endings."[30] The American Academy of Pediatrics noted that the work of Taylor et al. (1996) "suggests that there may be a concentration of specialized sensory cells in specific ridged areas of the foreskin."[31]

The World Health Organization (2007) states that "Although it has been argued that sexual function may diminish following circumcision due to the removal of the nerve endings in the foreskin and subsequent thickening of the epithelia of the glans, there is little evidence for this and studies are inconsistent."[32] Fink et al. (2002) reported "although many have speculated about the effect of a foreskin on sexual function, the current state of knowledge is based on anecdote rather than scientific evidence."[33] Masood et al. (2005) state that "currently no consensus exists about the role of the foreskin."[34] Schoen (2007) states that "anecdotally, some have claimed that the foreskin is important for normal sexual activity and improves sexual sensitivity.

The term 'gliding action' is used to describe the way the foreskin moves during sexual intercourse. This mechanism was described by Lakshamanan & Prakash (1980), stating that "[t]he outer layer of the prepuce in common with the skin of the shaft of the penis glides freely in a to and fro fashion..."[35] Several people have argued that the gliding movement of the foreskin is important during sexual intercourse. Warren & Bigelow (1994) state that gliding action would help to reduce the effects of vaginal dryness and that restoration of the gliding action is an important advantage of foreskin restoration.[36] O'Hara (2002) describes the gliding action, stating that it reduces friction during sexual intercourse, and suggesting that it adds "immeasurably to the comfort and pleasure of both parties".[37] Taylor (2000) suggests that the gliding action, where it occurs, may stimulate the nerves of the ridged band,[38] and speculates (2003) that the stretching of the frenulum by the rearward gliding action during penetration triggers ejaculation.[39] It is argued that removal of the foreskin results in a thickening of the glans because of chafing and abrasion from clothing, leading to loss of sensation. Removal of the foreskin can lead to trauma of the penis (friction irritation) during masturbation due to the loss of the gliding action of the foreskin and greater friction, requiring artificial lubrication. During sex, the loss of gliding action is also thought to cause pain, dryness and trauma of the vagina.[36] The trauma and abrasions of the vagina can lead to easier entry of sexually transmitted diseases.[27] One study showed that the loss of the foreskin resulted in decreased masturbatory pleasure and sexual enjoyment.[40] The gliding action of the foreskin is an aid to masturbation. The Nordic Association of Clinical Sexology states that the foreskin has numerous sexual functions and that "during sexual activity the foreskin is a functional and highly sensitive, erogenous structure, capable of providing pleasure to its owner and his potential partners."[25] The Royal Dutch Medical Association (2010) states that many sexologists view the foreskin as "a complex, erotogenic structure that plays an important role 'in the mechanical function of the penis during sexual acts, such as penetrative intercourse and masturbation'."[41]

Protective and immunological

The Nordic Association of Clinical Sexology (2013) states the foreskin has numerous important protective functions including protecting the penile glans from trauma.[25] Gairdner (1949) states that the foreskin protects the glans.[13] The foreskin can protect the glans from ammonia and feces for infants in diapers, and protect the glans from abrasions and trauma throughout life.[24] The fold of the prepuce maintains sub-preputial wetness, which mixes with exfoliated skin to form smegma. The American Academy of Pediatrics (1999) state that "no controlled scientific data are available regarding differing immune function in a penis with or without a foreskin."[42] Inferior hygiene has been associated with balanitis,[43] though excessive washing can cause non-specific dermatitis.[44]

Evolution

In primates, the foreskin is present in the genitalia of both sexes and likely has been present for millions of years of evolution.[45] The evolution of complex penile morphologies like the foreskin may have been influenced by females.[46][47][48]

The foreskin is also suggested to aid in the absorption of vaginal secretions, which contain hormones like vasopressin, that helps induce pair bonding and protective behaviors in the male.[49]

Conditions

Simmons et al. (2007) report that the foreskin's presence "frequently predisposes to medical problems, including balanitis, phimosis, sexually transmitted infection and penile cancer", and additionally state that "because we now are able to effectively treat foreskin related maladies, some societies are shifting toward foreskin preservation."[50]

Frenulum breve is a frenulum that is insufficiently long to allow the foreskin to fully retract, which may lead to discomfort during intercourse. Phimosis is a condition where the foreskin of an adult cannot be retracted properly. Before adulthood, the foreskin may still be separating from the glans.[51] Phimosis can be treated by stretching of the foreskin, by changing masturbation habits,[52] using topical steroid ointments, preputioplasty, or by the more radical option of circumcision. Posthitis is an inflammation of the foreskin.

A condition called paraphimosis may occur if a tight foreskin becomes trapped behind the glans and swells as a restrictive ring. This can cut off the blood supply, resulting in ischemia of the glans penis.

Lichen sclerosus is a chronic, inflammatory skin condition that most commonly occurs in adult women, although it may also be seen in men and children. Topical clobetasol propionate and mometasone furoate were proven effective in treating genital lichen sclerosus.[53]

Aposthia is a rare condition in which the foreskin is not present at birth.

Surgical and non-surgical modifications of the foreskin

Non-surgical stretching of the foreskin

The foreskin responds to the application of tension to cause expansion by creating new skin cells though the process of mitosis. The tissue expansion is permanent. Non-surgical stretching of the foreskin may be used to widen a narrow, non-retractable foreskin.[54] Stretching may be combined with the use of a steroid cream.[55][56] Beaugé recommends manual stretching for young males in preference to circumcision as a treatment for non-retractile foreskin because of the preservation of sexual sensation.[52]

Non-surgical foreskin restoration techniques (developed to help circumcised men 'regrow' a skin covering for the glans by tissue expansion) can be used by men with short foreskins to lengthen the natural foreskin so that it covers the glans.[57]

Surgical modifications

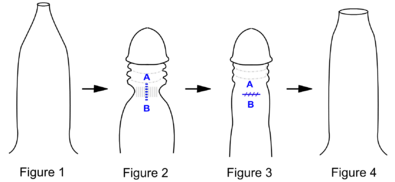

Fig 1. Penis with tight phimotic ring making it difficult to retract the foreskin.

Fig 2. Foreskin retracted under anaesthetic with the phimotic ring or stenosis constricting the shaft of the penis and creating a "waist".

Fig 3. Incision closed laterally.

Fig 4. Penis with the loosened foreskin replaced over the glans.

Preputioplasty is a minor procedure designed to relieve a tight foreskin without resorting to circumcision.

Circumcision is the removal of the foreskin, either partially or completely. It may be done for religious requirements or personal preferences surrounding hygiene and aesthetics. A non-surgical circumcision technique was introduced in 2009 with the Prepex device that induces necrosis of the foreskin with no cutting of live tissue.[58] Circumcision alters the penis's appearance, sensitivity, and function.[25]

Other practices include genital piercings involving the foreskin and slitting the foreskin.[59]

Langerhans cells

Langerhans cells are immature dendritic cells that are found in all areas of the penile epithelium,[60] but are most superficial in the inner surface of the foreskin.[60] Langerhans cells are also known to express the c-type lectin langerin.[60]

Foreskin-based medical and consumer products

Foreskins obtained from circumcision procedures are frequently used by biochemical and micro-anatomical researchers to study the structure and proteins of human skin. In particular, foreskins obtained from newborns have been found to be useful in the manufacturing of more human skin.[61]

Human growth factors derived from newborns' foreskins are used to make a commercial anti-wrinkle skin cream, TNS Recovery Complex.[62]

Foreskins of babies are also used for skin graft tissue,[63][64][65] and for β-interferon-based drugs.[66]

Foreskin fibroblasts have been used in biomedical research.[67]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Wright JE. Further to "the further fate of the foreskin". Update on the natural history of the foreskin. Med J Aust. 1994;160(3):134–5. PMID 8295581.

- ↑ Øster J. Further fate of the foreskin: Incidence of preputial adhesions, phimosis, and smegma among Danish schoolboys. Arch Dis Child. April 1968;43(228):200–202. doi:10.1136/adc.43.228.200. PMID 5689532.

- ↑ "Phimosis (tight foreskin)". NHS Choices. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

- ↑ "Male circumcision: Global trends and determinants of prevalence, safety and acceptability" (PDF). World Health Organization. 2007.

- ↑ Manu Shah (January 2008). The Male Genitalia: A Clinician's Guide to Skin Problems and Sexually Transmitted Infections. Radcliffe Publishing. pp. 37–. ISBN 978-1-84619-040-7.

- 1 2 3 4 Taylor, JR; Lockwood, AP; Taylor, AJ (1996). "The prepuce: specialized mucosa of the penis and its loss to circumcision". Br J Urol. 77 (2): 291–5. doi:10.1046/j.1464-410X.1996.85023.x. PMID 8800902.

- ↑ Dong G, Sheng-mei X, Hai-yang J, et al. Observation of Meissner's corpuscle on fused phimosis. J Guangdong Medical College. 2007.

- ↑ Haiyang J, Guxin W, Guo Dong G, Mingbo T et al.. Observation of Meissner's corpuscle in abundant prepuce and phimosis. J Modern Urol. 2005.

- ↑ Bhat GM, Bhat MA, Kour K, Shah BA. Density and structural variations of Meissner's corpuscle at different sites in human glabrous skin. J Anat Soc India. 2008;57(1):30–33.

- ↑ Winkelmann RK. The cutaneous innervation of human newborn prepuce. J Investigative Dermatol. 1956;26(1):53–67. doi:10.1038/jid.1956.5. PMID 13295637.

- ↑ Winkelmann RK. The mucocutaneous end-organ: the primary organized sensory ending in human skin. AMA Arch Dermatol. 1957;76(2):225–35. doi:10.1001/archderm.1957.01550200069015. PMID 13443512.

- ↑ College of Physicians; Surgeons of British Columbia (2009). "Circumcision (Infant Male)". Archived from the original (PDF) on May 31, 2012. Retrieved April 22, 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 Gaidner D. Fate of the Foreskin. BMJ. 1949;2(4642):1433–7. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.4642.1433. PMID 15408299.

- ↑ Øster J. Further fate of the foreskin: incidence of preputial adhesions, phimosis, and smegma among Danish Schoolboys. Arch Dis Child. 1968;43:200–3. doi:10.1136/adc.43.228.200. PMID 5689532.

- ↑ Thorvaldsen MA, Meyhoff H. Phimosis: Pathological or Physiological?. Ugeskrift for Læger. 2005;167(17):1858–62. PMID 15929334.

- ↑ Denniston GC, Hill G. Gairdner was wrong.. Can Fam Physician. 2010;56(1):986-7. PMID 20944034. PMC 2954072.

- ↑ "Circumcision of infant males" (PDF). RACP. p. 7.

- ↑ "The Significance and Frequency of Phimosis and Smegma". Male-initiation.net. 1966. Retrieved 2013-04-16.

- ↑ Chengzu, Liu (2011). "Health Care for Foreskin Conditions". Epidemiology of Urogenital Diseases. Beijing: People's Medical Publishing House.

- ↑ "Best Way to Cure Phimosis / Tight Foreskin". ehealthforum.com. 2007. Retrieved 2013-10-21.

- ↑ Xianze, Liang (2012). Tips on Puberty Health. Beijing: People's Education Press.

- ↑ Guochang, Huang (2010). General Surgery. Beijing: People's Medical Publishing House.

- ↑ "Male circumcision: Global trends and determinants of prevalence, safety and acceptability" (PDF). World Health Organization. p. 13.

- 1 2 3 4 Nordic Association of Clinical Sexologists. Statement on Non-therapeutic circumcision of boys; 10 October 2013 [Retrieved 6 January 2016].

- 1 2 Cold CJ, Taylor JR. The prepuce. BJU Int. 1999;83(Suppl. 1):34–44. doi:10.1046/j.1464-410x.1999.0830s1034.x. PMID 10349413.

- 1 2 Vern L. Bullough; Bonnie Bullough (14 January 2014). Human Sexuality: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 120–. ISBN 978-1-135-82502-7.

- ↑ Sorrells ML, Snyder JL, Reiss MD et al.. Fine-touch pressure thresholds in the adult penis.. BJU Int. 2007;99(4):864-9. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06685.x. PMID 17378847.

- ↑ Fleiss P, Hodges F, Van Howe RS. Immunological functions of the human prepuce. Sex Transm Infect. 1998;94(5):364-7. doi:10.1136/sti.74.5.364. PMID 10195034. PMC 1758142.

- ↑ Boyle, G; Goldman, R; Svoboda, J; Fernandez E (2002). "Male Circumcision: Pain, Trauma and Psychosexual Sequelae". Journal of Health Psychology. 7 (3): 329–343. doi:10.1177/135910530200700310. PMID 22114254.

- ↑ "American Academy of Pediatrics: Circumcision Policy Statement". Pediatrics. 103 (3): 686–693. March 1999. doi:10.1542/peds.103.3.686. PMID 10049981. Archived from the original on January 22, 2007.

- ↑ "Male circumcision: Global trends and determinants of prevalence, safety and acceptability" (PDF). World Health Organization. p. 16.

- ↑ Fink KS, Carson CC, DeVellis RF (May 2002). "Adult circumcision outcomes study: effect on erectile function, penile sensitivity, sexual activity and satisfaction". J. Urol. 167 (5): 2113–6. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(05)65098-7. PMID 11956453.

- ↑ Masood S, Patel HR, Himpson RC, Palmer JH, Mufti GR, Sheriff MK (2005). "Penile sensitivity and sexual satisfaction after circumcision: are we informing men correctly?". Urol. Int. 75 (1): 62–6. doi:10.1159/000085930. PMID 16037710.

- ↑ Lakshmanan S, Prakash S (1980). "Human prepuce: some aspects of structure and function". Indian Journal of Surgery. 44: 134–137.

The outer layer of the prepuce in common with the skin of the shaft of the penis glides freely in a to and fro fashion and has to be delicate and thin, as was observed in this study. [...] The inner lining of the projecting tubular part has the structure of the outer layer and adds to the thin gliding skin when retracted.

- 1 2 Warren, J; Bigelow J (September–October 1994). "The case against circumcision". Br J Sex Med: 6–8.

- ↑ O'Hara K (2002). Sex as Nature Intended It: The Most Important Thing You Need to Know about Making Love, but No One Could Tell You Until Now. Turning Point Publications. p. 72.

During intercourse, the natural penis shaft actually glides within its own shaft skin covering. This minimizes friction to the vaginal walls and opening, and to the shaft skin itself, adding immeasurably to the comfort and pleasure of both parties.

Friction is not entirely eliminated during natural intercourse but it is largely eliminated. Friction can take place in the lower vagina, but only if the man uses a stroke that exceeds the (forward and backward) gliding range of the shaft's extra skin. And in such a case, there will be friction only to the extent that the shaft exceeded its extra skin, which is uncommon since the natural penis has a propensity for short strokes. Primarily, it is the penis head that makes frictional contact with the vaginal walls, usually in the upper vagina where there is ample lubrication. [...] The gliding principle of natural intercourse is a two-way street—the vagina glides on the shaft skin while the shaft skin massages the penis shaft as it glides over it. - ↑ Taylor, J (2000). "Back and Forth". Pediatrics News. 34 (10): 50.

- ↑ Taylor JR (December 2003). "Evidence sketchy on circumcision and cervical cancer link". Can Fam Physician. 49: 1592. PMC 2214164

. PMID 14708921.

. PMID 14708921. - ↑ Kim; Pang (March 2007). "The effect of male circumcision on sexuality". BJU Int. 99 (3): 619–622. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06646.x. PMID 17155977.

- ↑ "Non-therapeutic circumcision of male minors (2010)". KNMG. 12 June 2010.

- ↑ "Circumcision policy statement. American Academy of Pediatrics. Task Force on Circumcision". Pediatrics. 103 (3): 686–93. March 1999. doi:10.1542/peds.103.3.686. PMID 10049981.

- ↑ O'Farrell N, Quigley M, Fox P. Association between the intact foreskin and inferior standards of male genital hygiene behaviour: a cross-sectional study. Int J STD AIDS. 2005;16(8):556–9. doi:10.1258/0956462054679151. PMID 16105191. O'Farrell N, Quigley M, Fox P (2005). "Association between the intact foreskin and inferior standards of male genital hygiene behaviour: a cross-sectional study". Int J STD AIDS. 16 (8): 556–9. doi:10.1258/0956462054679151. PMID 16105191.

- ↑ Birley HDL, Luzzi GA, Bell R. Clinical features and management of recurrent balanitis; association with atopy and genital washing. Genitourin Med. 1993;69(5):400–3. doi:10.1136/sti.69.5.400. PMID 8244363.

- ↑ Martin, Robert D. (1990). Primate Origins and Evolution: A Phylogenetic Reconstruction. New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-08565-4.

- ↑ Diamond, Jared M. (1997). Why Sex is Fun: The Evolution of Human Sexuality. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0-465-03126-9.

- ↑ Darwin, Charles (1871). The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex. London: Murray. ISBN 1-148-75093-2.

- ↑ Short, RV (1981). "Sexual selection in man and the great apes". Graham CE, ed. Reproductive Biology of the Great Apes: Comparative and Biomedical Perspectives. New York: Academic Press.

- ↑ Bowman, Edwin A. (2010). "An Explanation for the Shape of the Human Penis" (PDF). Arch Sex Behav. 43 (39): 216–216. doi:10.1007/s10508-009-9567-6. Retrieved October 1, 2013.

- ↑ Simmons MN, Jones JS. Male genital morphology and function: an evolutionary perspective. J Urol. 2007;177(5):1625–31. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2007.01.011. PMID 17437774. Simmons MN, Jones JS (May 2007). "Male genital morphology and function: an evolutionary perspective". J. Urol. 177 (5): 1625–31. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2007.01.011. PMID 17437774.

- ↑ Kayaba H, Tamura H, Kitajima S, et al. Analysis of shape and retractability of the prepuce in 603 Japanese boys. J Urol. 1996;156(5):1813–5. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(01)65544-7. PMID 8863623.

- 1 2 Beaugé M. The causes of adolescent phimosis. Br J Sex Med. 1997;(September–October):26.

- ↑ Chi C, Kirtschig G, Bakio M, et aL.. Topical interventions for genital lichen sclerosus. Cochrane. 2011. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008240.pub2. PMID 22161424.

- ↑ Dunn HP. Non-surgical management of phimosis. Aust N Z J Surg. 1989;59(12):963. doi:10.1111/j.1445-2197.1989.tb07640.x. PMID 2597103.

- ↑ Zampieri N, Corroppolo M, Giacomello L, et al.. Phimosis: Stretching methods with or without application of topical steroids?. J Pediatr. 2005;147(5):705-6. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.07.017. PMID 16291369.

- ↑ Ghysel C, Vander Eeckt K, Bogaert GA.. Long-term efficiency of skin stretching and a topical corticoid cream application for unretractable foreskin and phimosis in prepubertal boys. Urol Int. 2009;82(1):81-8. doi:10.1159/000176031. PMID 19172103.

- ↑ Collier R. Whole again: the practice of foreskin restoration. CMAJ. 2011;183(18):2092-3. doi:10.1503/cmaj.109-4009. PMID 22083672.

- ↑ Adams, Patrick. "In One Simple Tool, Hope for H.I.V. Prevention". The New York Times Company. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- ↑ "Paraphimosis : Article by Jong M Choe, MD, FACS". eMedicine. Retrieved 2012-07-16.

- 1 2 3 McCoombe SG, Short RV. Potential HIV-1 target cells in the human penis. AIDS. 2006;20(11):1491–5. doi:10.1097/01.aids.0000237364.11123.98. PMID 16847403.

- ↑ McKie, Robin (1999-04-04). "Foreskins for Skin Grafts". The Toronto Star.

- ↑ "SkinMedica Seeks Niche in Skin-Care Drugs, Products". Orange County Business Journal. August 5, 2002. Retrieved February 11, 2011.

- ↑ High-Tech Skinny on Skin Grafts; 1999-02-16 [archived October 10, 2008; Retrieved 2008-08-20].

- ↑ Grand DJ. Medscape. Skin Grafting; August 15, 2011 [Retrieved August 18. 2012].

- ↑ Amst, Catherine; Carey, John (July 27, 1998). "Biotech Bodies". www.businessweek.com. The McGraw-Hill Companies Inc. Retrieved 2008-08-20.

- ↑ Cowan, Alison Leigh (April 19, 1992). "Wall Street; A Swiss Firm Makes Babies Its Bet". New York Times:Business. New York Times. Retrieved 2008-08-20.

- ↑ Hovatta O, Mikkola M, Gertow A, et al.. A culture system using human foreskin fibroblasts as feeder cells allows production of human embryonic stem cells. Hum Reprod. 2003;18(7):1404–9. doi:10.1093/humrep/deg290. PMID 12832363.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Foreskin. |

- Foreskin.org - Many detailed pictures of the human male foreskin

- Infant foreskin care at Kidshealth.org.nz

- Our son is not circumcised. When will his foreskin retract? by American Academy of Pediatrics

- Management of foreskin conditions - Statement from the British Association of Paediatric Urologists on behalf of the British Association of Paediatric Surgeons and The Association of Paediatric Anaesthetists (2007).

- Davenport M (1996). "ABC of general surgery in children. Problems with the penis and prepuce". British Medical Journal. 312 (7026): 299–301. doi:10.1136/bmj.312.7026.299. PMC 2349890

. PMID 8611792.

. PMID 8611792. - Fleiss P, Hodges F, Van Howe RS. Immunological functions of the human prepuce. Sex Transm Infect. 1998;94(5):364-7. doi:10.1136/sti.74.5.364. PMID 10195034. PMC 1758142.

- Cold CJ, Taylor JR. The prepuce. BJU Int. 1999;83(Suppl. 1):34-44. doi:10.1046/j.1464-410x.1999.0830s1034.x. PMID 10349413.

- Cold CJ, McGrath KA. Anatomy and histology of the penile and clitoral prepuce in primates. Male and Female Circumcision 1999

- Anatomy photo:42:01-0107 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center - "The Male Perineum and the Penis: The Surface Anatomy of the Penis"