Types of cheese

There are several types of cheese, which are grouped or classified according to criteria such as length of ageing, texture, methods of making, fat content, animal milk, country or region of origin, etc. The method most commonly and traditionally used is based on moisture content, which is then further narrowed down by fat content and curing or ripening methods.[1][2] The criteria may either be used singly or in combination,[3] but with no single method being universally used.[4] The combination of types produces around 500 different varieties recognised by the International Dairy Federation,[1] over 400 identified by Walter and Hargrove, over 500 by Burkhalter, and over 1,000 by Sandine and Elliker.[5] Some attempts have been made to rationalise the classification of cheese; a scheme was proposed by Pieter Walstra that uses the primary and secondary starter combined with moisture content, and Walter and Hargrove suggested classifying by production methods. This last scheme results in 18 types, which are then further grouped by moisture content.[1]

Fresh, whey, and stretched curd cheeses

The main factor in categorizing these cheeses is age. Fresh cheeses without additional preservatives can spoil in a matter of days.

For these simplest cheeses, milk is curdled and drained, with little other processing. Examples include cottage cheese, cream cheese, curd cheese, farmer cheese, caș, chhena, fromage blanc, queso fresco, paneer, and fresh goat's milk chèvre. Such cheeses are soft and spreadable, with a mild flavour.

Whey cheeses are fresh cheeses made from whey, a by-product from the process of producing other cheeses which would otherwise be discarded. Corsican brocciu, Italian ricotta, Romanian urda, Greek mizithra, Cypriot anari cheese and Norwegian Brunost are examples. Brocciu is mostly eaten fresh, and is as such a major ingredient in Corsican cuisine, but it can also be found in an aged form.

Traditional pasta filata cheeses such as Mozzarella also fall into the fresh cheese category. Fresh curds are stretched and kneaded in hot water to form a ball of Mozzarella, which in southern Italy is usually eaten within a few hours of being made. Stored in brine, it can easily be shipped, and it is known worldwide for its use on pizza.

Moisture: soft to hard

Categorizing cheeses by moisture content or firmness is a common but inexact practice. The lines between "soft", "semi-soft", "semi-hard", and "hard" are arbitrary, and many types of cheese are made in softer or firmer variants. The factor that controls cheese hardness is moisture content, which depends on the pressure with which it is packed into moulds, and upon aging time.

- Soft cheese

Cream cheeses are not matured. Brie and Neufchâtel are soft-type cheeses that mature for more than a month.

- Semi-soft cheese

Semi-soft cheeses, and the sub-group Monastery, cheeses have a high moisture content and tend to be mild-tasting. Some well-known varieties include Havarti, Munster and Port Salut.

- Medium-hard cheese

Cheeses that range in texture from semi-soft to firm include Swiss-style cheeses such as Emmental and Gruyère. The same bacteria that give such cheeses their eyes also contribute to their aromatic and sharp flavours. Other semi-soft to firm cheeses include Gouda, Edam, Jarlsberg, Cantal, and Cașcaval. Cheeses of this type are ideal for melting and are often served on toast for quick snacks or simple meals.

- Semi-hard or hard cheese

Harder cheeses have a lower moisture content than softer cheeses. They are generally packed into moulds under more pressure and aged for a longer time than the soft cheeses. Cheeses that are classified as semi-hard to hard include the familiar Cheddar, originating in the village of Cheddar in England but now used as a generic term for this style of cheese, of which varieties are imitated worldwide and are marketed by strength or the length of time they have been aged. Cheddar is one of a family of semi-hard or hard cheeses (including Cheshire and Gloucester), whose curd is cut, gently heated, piled, and stirred before being pressed into forms. Colby and Monterey Jack are similar but milder cheeses; their curd is rinsed before it is pressed, washing away some acidity and calcium. A similar curd-washing takes place when making the Dutch cheeses Edam and Gouda.

Hard cheeses — "grating cheeses" such as Parmesan and Pecorino Romano—are quite firmly packed into large forms and aged for months or years.

Source of milk used

Some cheeses are categorized by the source of the milk used to produce them or by the added fat content of the milk from which they are produced. While most of the world's commercially available cheese is made from cow's milk, many parts of the world also produce cheese from goats and sheep. Well-known examples include Roquefort (produced in France) and Pecorino (produced in Italy) from ewe's milk. One farm in Sweden also produces cheese from moose's milk.[6] Sometimes cheeses marketed under the same name are made from milk of different animal—Feta style cheeses, for example, are made from sheep's milk in Greece and from cow's milk elsewhere.

Double cream cheeses are soft cheeses of cow's milk enriched with cream so that their FDM is 60–75% or, in the case of triple creams, at least 75%.

Mold

There are three main categories of cheese in which the presence of mold is an important feature: soft ripened cheeses, washed rind cheeses and blue cheeses.

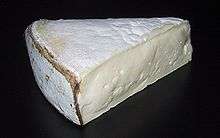

- Soft-ripened

Soft-ripened cheeses begin firm and rather chalky in texture, but are aged from the exterior inwards by exposing them to mold. The mold may be a velvety bloom of P. camemberti that forms a flexible white crust and contributes to the smooth, runny, or gooey textures and more intense flavors of these aged cheeses. Brie and Camembert, the most famous of these cheeses, are made by allowing white mold to grow on the outside of a soft cheese for a few days or weeks. Goat's milk cheeses are often treated in a similar manner, sometimes with white molds (Chèvre-Boîte) and sometimes with blue.

- Washed-rind

Washed-rind cheeses are soft in character and ripen inwards like those with white molds; however, they are treated differently. Washed-rind cheeses are periodically cured in a solution of saltwater brine and/or mold-bearing agents that may include beer, wine, brandy and spices, making their surfaces amenable to a class of bacteria Brevibacterium linens (the reddish-orange "smear bacteria") that impart pungent odors and distinctive flavors, and produce a firm, flavorful rind around the cheese.[7] Washed-rind cheeses can be soft (Limburger), semi-hard, or hard (Appenzeller). The same bacteria can also have some impact on cheeses that are simply ripened in humid conditions, like Camembert. The process requires regular washings, particularly in the early stages of production, making it quite labor-intensive compared to other methods of cheese production.

- Smear-ripened

Some washed-rind cheeses are also smear-ripened with solutions of bacteria or fungi, most commonly Brevibacterium linens, Debaryomyces hansenii, and/or Geotrichum candidum[8]) which usually gives them a stronger flavor as the cheese matures.[8] In some cases, older cheeses are smeared on young cheeses to transfer the microorganisms. Many, but not all, of these cheeses have a distinctive pinkish or orange coloring of the exterior. Unlike with other washed-rind cheeses, the washing is done to ensure uniform growth of desired bacteria or fungi and to prevent the growth of undesired molds.[9] Notable examples of smear-ripened cheeses include Munster and Port Salut.

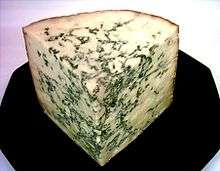

- Blue

So-called blue cheese is created by inoculating a cheese with Penicillium roqueforti or Penicillium glaucum. This is done while the cheese is still in the form of loosely pressed curds, and may be further enhanced by piercing a ripening block of cheese with skewers in an atmosphere in which the mold is prevalent. The mold grows within the cheese as it ages. These cheeses have distinct blue veins, which gives them their name and, often, assertive flavors. The molds range from pale green to dark blue, and may be accompanied by white and crusty brown molds. Their texture can be soft or firm. Some of the most renowned cheeses are of this type, each with its own distinctive color, flavor, texture and aroma. They include Roquefort, Gorgonzola and Stilton.

Brined

Brined or pickled cheese is matured in a solution of brine in an airtight or semi-permeable container. This process gives the cheese good stability, inhibiting bacterial growth even in hot countries.[10] Brined cheeses may be soft or hard, varying in moisture content, and in colour and flavour, according to the type of milk used; though all will be rindless, and generally taste clean, salty and acidic when fresh, developing some piquancy when aged, and most will be white.[10] Varieties of brined cheese include bryndza, feta, halloumi, and sirene.[10] Brined cheese is the main type of cheese produced and eaten in the Middle East and Mediterranean areas.[11]

Processed

Processed cheese is made from traditional cheese and emulsifying salts, often with the addition of milk, more salt, preservatives, and food colouring. Its texture is consistent, and melts smoothly. It is sold packaged and either pre-sliced or unsliced, in several varieties. Some are sold as sausage-like logs and chipolatas (mostly in Germany and USA), and some are moulded into the shape of animals and objects. It is also available in aerosol cans in some countries.

Some, if not most, varieties of processed cheese are made using a combination of real cheese waste (which is steam-cleaned, boiled and further processed) whey powders, and various mixtures of vegetable and/or palm oils and fats. Some processed "cheese" slices contain as little as 2-6% cheese; some have smoke flavours added.

References

- 1 2 3 Patrick F. Fox, P. F. Fox. Fundamentals of cheese science. Springer, 2000. p. 388. Retrieved 21 March 2011.

- ↑ "Classification of Cheese". www.egr.msu.edu. Retrieved 23 March 2011.

- ↑ "Classification of cheese types using calcium and pH". www.dairyscience.info. Retrieved 23 March 2011.

- ↑ Barbara Ensrud, (1981) The Pocket Guide to Cheese, Lansdowne Press/Quarto Marketing Ltd., ISBN 0-7018-1483-7

- ↑ Patrick F. Fox, P. F. Fox. Cheese: chemistry, physics and microbiology, Volume 1. Springer, 1999. p. 1. Retrieved 23 March 2011.

- ↑ "Moose milk makes for unusual cheese". The Globe and Mail. 26 June 2004. Retrieved 27 August 2007.

- ↑ Washed Rind Cheese at Practically Edible Food Encyclopedia

- 1 2 Fox, Patrick. Cheese: Chemistry, Physics and Microbiology. p. 199.

- ↑ Fox, Patrick. Cheese: Chemistry, Physics and Microbiology. p. 200.

- 1 2 3 A. Y. Tamime. Brined cheeses. Wiley-Blackwell, 2006. p. 2. Retrieved 21 March 2011.

- ↑ A. Y. Tamime. Feta and Related Cheeses. Woodhead Publishing, 1991. p. 9. Retrieved 21 March 2011.