G.fast

G.fast is a digital subscriber line (DSL) protocol standard for local loops shorter than 500 m, with performance targets between 150 Mbit/s and 1 Gbit/s, depending on loop length.[1] High speeds are only achieved over very short loops. Although G.fast was initially designed for loops shorter than 250 meters, Sckipio in early 2015 demonstrated G.fast delivering speeds over 100 megabits nearly 500 meters and the EU announced a research project that is Gigabits Over the Legacy Drop (GOLD) project.[2]

Formal specifications have been drafted as ITU-T G.9700 and G.9701, with approval of G.9700 granted in April 2014 and approval of G.9701 granted on December 5, 2014.[1][3][4][5] Development was coordinated with the Broadband Forum's FTTdp (fiber to the distribution point) project.[6][7] The name G.fast is an acronym for fast access to subscriber terminals;[8] the letter G stands for the ITU-T G series of recommendations. Limited demonstration hardware was demonstrated in mid-2013.[9] The first chipsets were introduced in October 2014, with commercial hardware introduced in 2015, and first deployments started in 2016.[10][11][12]

Technology

Modulation

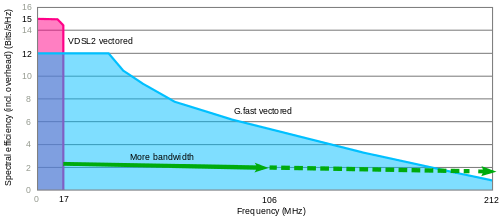

In G.fast, data is modulated using discrete multi-tone (DMT) modulation, as in VDSL2 and most ADSL variants.[13] G.fast modulates up to 12 bit per DMT frequency carrier, reduced from 15 in VDSL2 for complexity reasons.[14]

The first version of G.fast will specify 106 MHz profiles, with 212 MHz profiles planned for future amendments, compared to 8.5, 17.664, or 30 MHz profiles in VDSL2.[1] This spectrum overlaps the FM broadcast band between 87.5 and 108 MHz, as well as various military and government radio services. To limit interference to those radio services, the ITU-T G.9700 recommendation, also called G.fast-psd, specifies a set of tools to shape the power spectral density of the transmit signal;[8] G.9701, codenamed G.fast-phy, is the G.fast physical layer specification.[6][15] To enable co-existence with ADSL2 and the various VDSL2 profiles, the start frequency can be set to 2.2, 8.5, 17.664, or 30 MHz, respectively.[1]

Duplex

G.fast uses time-division duplexing (TDD), as opposed to ADSL2 and VDSL2, which use frequency-division duplexing.[1] Support for symmetry ratios between 90/10 and 50/50 is mandatory, 50/50 to 10/90 is optional.[1] The discontinuous nature of TDD can be exploited to support low-power states, in which the transmitter and receiver remain disabled for longer intervals than would be required for alternating upstream and downstream operation. This optional discontinuous operation allows a trade-off between throughput and power consumption.[1]

Channel coding

The forward error correction (FEC) scheme using trellis coding and Reed-Solomon coding is similar to that of VDSL2.[1] FEC does not provide good protection against impulse noise. To that end, the impulse noise protection (INP) data unit retransmission scheme specified for ADSL2, ADSL2+, and VDSL2 in G.998.4 is also present in G.fast.[1] To respond to abrupt changes in channel or noise conditions, fast rate adaptation (FRA) enables rapid (<1 ms) reconfiguration of the data rate.[1][16]

Vectoring

Performance in G.fast systems is limited to a large extent by crosstalk between multiple wire pairs in a single cable.[13][14] Self-FEXT (far-end crosstalk) cancellation, also called vectoring, is mandatory in G.fast. Vectoring technology for VDSL2 was previously specified by the ITU-T in G.993.5, also called G.vector. The first version of G.fast will support an improved version of the linear precoding scheme found in G.vector, with non-linear precoding planned for a future amendment.[1][13] Testing by Huawei and Alcatel shows that non-linear precoding algorithms can provide an approximate data rate gain of 25% compared to linear precoding in very high frequencies; however, the increased complexity leads to implementation difficulties, higher power consumption, and greater costs.[13] Since all current G.fast implementations are limited to 106 MHz, non-linear precoding yields little performance gain. Instead, current efforts to deliver a gigabit are focusing on bonding, power and more bits per hertz.

Performance

In tests performed in July 2013 by Alcatel-Lucent and Telekom Austria using prototype equipment, aggregate (sum of uplink and downlink) data rates of 1.1 Gbit/s were achieved at a distance of 70 m and 800 Mbit/s at a distance of 100 m, in laboratory conditions with a single line.[14][17] On older, unshielded cable, aggregate data rates of 500 Mbit/s were achieved at 100 m.[14]

| Distance | Performance target[B] |

|---|---|

| <100 m, FTTB | 500–1000 Mbit/s |

| 100 m | 500 Mbit/s |

| 200 m | 200 Mbit/s |

| 250 m | 150 Mbit/s |

| 500 m | 100 Mbit/s[18] |

- A A straight loop is a subscriber line (local loop) without bridge taps.

- B The listed values are aggregate (sum of uplink and download) data rates.

Deployment scenarios

The Broadband Forum is investigating architectural aspects of G.fast and has, as of May 2014, identified 23 use cases.[1] Deployment scenarios involving G.fast bring fiber closer to the customer than traditional VDSL2 FTTN (fiber to the node), but not quite to the customer premises as in FTTH (fiber to the home).[12][19] The term FTTdp (fiber to the distribution point) is commonly associated with G.fast, similar to how FTTN is associated with VDSL2. In FTTdp deployments, a limited number of subscribers at a distance of up to 200–300 m are attached to one fiber node, which acts as DSL access multiplexer (DSLAM).[12][19] As a comparison, in ADSL2 deployments the DSLAM may be located in a central office (CO) at a distance of up to 5 km from the subscriber, while in some VDSL2 deployments the DSLAM is located in a street cabinet and serves hundreds of subscribers at distances up to 1 km.[12][14] VDSL2 is also widely used in fiber to the basement.[20]

A G.fast FTTdp fiber node has the approximate size of a large shoebox and can be mounted on a pole or underground.[12][21] In a FTTB (fiber to the basement) deployment, the fiber node is in the basement of a multi-dwelling unit (MDU) and G.fast is used on the in-building telephone cabling.[19] In a fiber to the front yard scenario, each fiber node serves a single home.[19] The fiber node may be reverse-powered by the subscriber modem.[19] For the backhaul of the FTTdp fiber node, the Broadband Forum's FTTdp architecture provides GPON, XG-PON1, EPON, 10G-EPON, point-to-point fiber Ethernet, and bonded VDSL2 as options.[7][22]

Former FCC chief of staff Blair Levin has expressed skepticism that US ISPs have enough incentives to adopt G.fast technology.[23]

GOLD project

The Gigabits Over the Legacy Drop (GOLD) project is the third project of the 4GBB trilogy of EUREKA CELTIC cluster projects with the overall goal to move broadband deployment forward closing the gap between existing DSL solutions and an all-optical access network. It is coordinated by Lund University, Sweden and has 14 partners from 8 countries including service providers Deutsche Telekom (Germany), British Telecom (UK), Orange S.A. (France); equipment vendors ADTRAN GmbH (Germany), Alcatel-Lucent Bell Labs (Belgium), Ericsson (Sweden), SAGEMCOM (France), and TELNET Redes Inteligentes SA (Spain); chip vendors Marvell (Spain) and Sckipio Technologies (Israel); and researchers at Lund University (Sweden), Southampton University (UK), Newcastle University (UK) and TNO (Netherlands).[24][25]

The GOLD project will continue the work on the G.fast standard and boost its usability in dense city areas. The goal is to develop alternative backhauling options based on copper instead of fibre. This could lead to significant cost reductions in the network, particularly within dense urban areas in Europe.[26][27]

The goal of the GOLD project is to:

- Continue the work on G.fast standards to develop the planned second version of the G.fast standard.

- Further develop and spread know-how around deployment practices in order to ensure that G.fast becomes a market success.

- Boost the usability of G.fast towards dense city areas by developing an alternative backhauling option based on copper instead of fibre. This simplifies G.fast deployment significantly (less fibre digging) and opens a potential mass market for G.fast.

- Go beyond the first standard by initiating the planned second version of the standard promising a doubling of the bandwidth reaching 200 MHz, by exploring multiple-gigabit copper access.

The 3-year project started in January 2015 and will run until December 2017.

XG-fast

Traditionally, copper network operators complement a fiber-to-the-home (FTTH) strategy with a hybrid fiber-copper deployment in which fiber is gradually brought closer to the consumer, and digital subscriber line (DSL) technology is used for the remaining copper network.

Bell Labs, Alcatel-Lucent proposed the system concepts of XG-FAST, the 5th generation broadband (5GBB) technology capable of delivering a 10 Gb/s data rate over short copper pairs. With a hardware proof-of-concept platform, it is demonstrated that multi-gigabit rates are achievable over typical drop lengths of up to 130 m, with net data rates exceeding 10 Gb/s on the shortest loops.[28]

The XG-FAST technology will make fiber-to-the-frontage (FTTF) deployments feasible, which avoids many of the hurdles accompanying a traditional FTTH roll-out. Single subscriber XG-FAST devices would be an integral component of FTTH deployments, and as such help accelerate a worldwide roll-out of FTTH services. Moreover, an FTTF XG-FAST network is able to provide a remotely managed infrastructure and a cost-effective multi-gigabit backhaul for future 5G wireless networks.[28][29][30]

G.fast internet service providers

Swisscom

On 2016-10-18 Swisscom (Switzerland) Ltd launched G.fast in Switzerland after a more than four-year project phase. In a first step G.fast will be deployed in the FTTdp environment. Swisscom works together with its technology partner Huawei which is the supplier of the G.fast micro-nodes (DSLAMs) that are installed in the manholes.

[31]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Van der Putten, Frank (2014-05-20). "Overview of G.fast: Summary overview and timeline" (PDF). G.fast Summit 2014. Retrieved 2014-10-09.

- ↑ "100+ megabits 400 meters.". G.fast News. Fast Net News. February 4, 2015.

- ↑ "G.9700 : Fast access to subscriber terminals (G.fast) - Power spectral density specification". ITU-T. 2014-12-19. Retrieved 2015-02-03.

- ↑ "G.9701 : Fast access to subscriber terminals (G.fast) - Physical layer specification". ITU-T. 2014-12-18. Retrieved 2015-02-03.

- ↑ "G.fast broadband standard approved and on the market". ITU-T. 2014-12-05. Retrieved 2015-02-03.

- 1 2 "New ITU broadband standard fast-tracks route to 1Gbit/s". ITU-T. 2013-12-11. Retrieved 2014-02-13.

- 1 2 Starr, Tom (2014-05-20). "Accelerating copper up to a Gigabit in the Broadband Forum" (PDF). G.fast Summit 2014. Broadband Forum. Retrieved 2015-03-13.

- 1 2 "ITU-T work programme - G.9700 (ex G.fast-psd) - Fast access to subscriber terminals (FAST) - Power spectral density specification". ITU-T. 2014-01-29. Retrieved 2014-02-14.

- ↑ Ricknäs, Mikael (2013-07-02). "Alcatel-Lucent gives DSL networks a gigabit boost". PCWorld. Retrieved 2014-02-13.

- ↑ "Sckipio Unveils G.fast Chipsets". lightreading.com. 2014-10-07. Retrieved 2014-10-09.

- ↑ Hardy, Stephen (2014-10-22). "G.fast ONT available early next year says Alcatel-Lucent". lightwaveonline.com. Retrieved 2014-10-23.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Verry, Tim (2013-08-05). "G.fast Delivers Gigabit Broadband Speeds To Customers Over Copper (FTTdp)". PC Perspective. Retrieved 2014-02-13.

- 1 2 3 4 "G.fast: Moving Copper Access into the Gigabit Era". Huawei. Retrieved 2014-02-13.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Spruyt, Paul; Vanhastel, Stefaan (2013-07-04). "The Numbers are in: Vectoring 2.0 Makes G.fast Faster". TechZine. Alcatel Lucent. Retrieved 2014-02-13.

- ↑ "ITU-T work programme - G.9701 (ex G.fast-phy) - Fast Access to Subscriber Terminals (G.fast) - Physical layer specification". ITU-T. 2014-01-07. Retrieved 2014-02-14.

- ↑ Brown, Les (2014-05-20). "Overview of G.fast: Key functionalities and technical overview of draft Recommendations G.9700 and G.9701" (PDF). G.fast Summit 2014. Retrieved 2015-03-13.

- ↑ Ricknäs, Mikael (2013-12-12). "ITU standardizes 1Gbps over copper, but services won't come until 2015". IDG News Service. Retrieved 2014-02-13.

- ↑ "Suddenly, G.fast is 500 meters, not 200 meters".

- 1 2 3 4 5 Wilson, Steve (2012-08-14). "G.fast: a question of commercial radio, manholes, prison sentences and indoor vs outdoor engineers". telecoms.com. Retrieved 2014-02-13.

- ↑ "Planning of Fibre to the Curb Using G. Fast in Multiple Roll-Out Scenarios - Volume 2, No.1, March 2014 - Lecture Notes on Information Theory". LNIT. Retrieved 2014-07-19.

- ↑ Maes, Jochen (2014-05-20). "The Future of Copper" (PDF). G.fast Summit 2014. Alcatel-Lucent. Retrieved 2015-03-13.

- ↑ Gurrola, Elliott (2014-08-01). "PON/xDSL Hybrid Access Networks". PON/xDSL Hybrid Access Networks. Elsevier Optical Switching and Networking.

- ↑ Talbot, David (2013-07-30). "Adapting Old-Style Phone Wires for Superfast Internet: Alcatel-Lucent has demonstrated fiber-like data-transfer speeds over telephone wiring—but will ISPs adopt it?". MIT Technology Review. Retrieved 2014-02-13.

- ↑ "GOLD project: Gigabits over the Legacy Drop". 4GBB.eu.

- ↑ "Project GOLD: Gigabits Over the Legacy Drop". CelticPlus.eu.

- ↑ "Multi-gigabit access via copper". CelticPlus.eu.

- ↑ "HFCC/G.fast – Hybrid fibre-copper connectivity using G.fast technology". Eurescom.eu.

- 1 2 "IEEE Xplore Document - XG-fast: the 5th generation broadband". IEEE.org.

- ↑ "NBN Co shoots for faster copper speeds with XG.FAST trial". itnews.com.au.

- ↑ "XG.FAST won't obviate need for copper replacement, says Internet Australia". Delimiter.com.au.

- ↑ "Swisscom press release 2016/10/18". swisscom.com.