Gallaecian language

| Gallaecian | |

|---|---|

| Native to | Iberian Peninsula |

| Era | attested beginning of the first millennium CE |

|

Indo-European

| |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 |

None (mis) |

| Glottolog | None |

Northwestern Hispano-Celtic or Gallaecian is an extinct Celtic language, and was one of the Hispano-Celtic languages.[1] It was spoken at the beginning of the first millennium CE, in the northwest corner of the Iberian Peninsula that became the Roman province of Gallaecia, and is now divided between the modern regions of Galicia, western Asturias, León and northern Portugal.[2][3][4][5]

Overview

As with the Illyrian and Ligurian languages, the surviving corpus of Gallaecian is composed of isolated words and short sentences contained in local Latin inscriptions or glossed by classical authors, together with a number of names – anthroponyms, ethnonyms, theonyms, toponyms – contained in inscriptions, or surviving as the names of places, rivers or mountains. In addition, many isolated words of Celtic origin preserved in the present-day Romance languages of north-west Spain and Portugal, are likely to have been inherited from ancient Gallaecian.[6]

Classical authors such as Pomponius Mela and Pliny the Elder wrote about the existence of Celtic[7] and non-Celtic populations in Gallaecia and Lusitania, but several modern scholars have postulated Lusitanian and Gallaecian as a single archaic Celtic language.[8] Others point to major unresolved problems for this hypothesis, such as the mutually incompatible phonetic features, most notably the proposed preservation of *p in Lusitanian and the inconsistent outcome of the vocalic liquid consonants, so addressing Lusitanian as a non-Celtic language and unrelated to Gallaecian, although cultural influences were likely.[9][10][11]

Characteristics

Some of the main characteristic of Gallaecian shared with Celtiberian and the other Celtic languages were (reconstructed forms are Proto-Celtic unless otherwise indicated):

- Indo-European *-ps- and *-ks- became *-xs- and were then reduced to -s-: place name AVILIOBRIS from *Awil-yo-brix-s < Proto-Celtic *Awil-yo-brig-s 'Windy hill(fort)',[12][13] modern place name Osmo (Cenlle, Osamo 928 AD) from *Uχsamo- 'the highest one'.[14]

- Original PIE *p has disappeared, having become a *φ sound before being lost completely:[15][16] place names C(ASTELLO) OLCA from *φolkā- 'Overturned', C(ASTELLO) ERITAECO from *φerito- 'surrounded, enclosed', personal name ARCELTIUS, from *φari-kelt-y-os; place name C(ASTELLO) ERCORIOBRI, from *φeri-kor-y-o-brig-s 'Overshooting hillfort'; place name C(ASTELLO) LETIOBRI,[17] from *φle-tyo-brig-s 'wide hillfort', or *φlei-to-brig-s 'grey hillfort';[18] place name Iria Flavia, from *φīweryā- (nominative *φīwerī) 'fertile' (feminine form, cf. Sanskrit feminine pīvari- "fat");[19] place name ONTONIA, from *φont-on- 'path';[20] personal name LATRONIUS,[21] to *φlā-tro- 'place; trousers'; personal name ROTAMUS, to *φro-tamo- 'foremost';[22] modern place names Bama (Touro, Vama 912) to *uφamā-[23] 'the lowest one, the bottom' (feminine form), Iñobre (Rianxo) to *φenyo-brix-s[24] 'Hill(fort) by the water', Bendrade (Oza dos Ríos) to *Vindo-φrātem 'White fortress', and Baiordo (Coristanco) to *Bagyo-φritu-, where the second element is proto-Celtic for 'ford'.[25] Galician appellative words leira 'flat patch of land' from *φlāryā,[26] lavego 'plough' from *φlāw-aiko-,[27] laxe 'flagstone', from medieval lagena, from *φlagĭnā,[28] rega and rego 'furrow' from *φrikā.[29]

- The frequent instances of preserved PIE /p/ are assigned by some authors, namely Carlos Búa[30] and Jürgen Untermann, to a single and archaic Celtic language spoken in Gallaecia, Asturia and Lusitania, while others (Francisco Villar, Blanca María Prósper, Patrizia de Bernado Stempel, Jordán Colera) consider that they belong to a Lusitanian or Lusitanian-like dialect or group of dialects spoken in northern Iberia along with (but different from) Western Hispano-Celtic:[31]

- in Galicia: divinity names and epithets PARALIOMEGO, PARAMAECO, POEMANAE, PROENETIAEGO, PROINETIE, PEMANEIECO, PAMUDENO, MEPLUCEECO; place names Lapatia, Paramo, Pantiñobre if from *palanti-nyo-brig-s (Búa); Galician appellative words lapa 'stone, rock' (cfr. Lat. lapis) and pala 'stone cavity', from *palla from *plh-sa (cfr. germ. fels, o.Ir. All).

- in Asturias the ethnic name Paesici; personal names PENTIUS, PROGENEI; divinity name PECE PARAMECO; in León and Bragança place names PAEMEIOBRIGENSE, Campo Paramo, Petavonium.

- in other northwestern areas: place names Pallantia, Pintia, Segontia Paramica; ethnic name Pelendones.

- Indo-European sonants between vowels, *n̥, and *m̥ have become an, am; *r̥, and *l̥ have become ri, li:[32] place name Brigantia from *brig-ant-yā < Proto-Celtic *br̥g-n̥t-y-ā < post-Proto-Indo-European (post-PIE) *bʰr̥gʰ-n̥t-y-ā 'The towering one, the high one'; modern place names Berganzo, Berganciños, Bergaña;[33] ancient place names NEMETOBRIGA, COELIOBRIGA, TALABRIGA with second element *brigā < Proto-Celtic *br̥g-ā < post-PIE *bʰr̥gʰ-ā 'high place',[34] and AVILIOBRIS, MIOBRI, AGUBRI with second element *bris < *brix-s < Proto-Celtic *brig-s < *br̥g-s < PIE *bʰr̥gʰ-s 'hill(fort)';[35] cf. English cognate borough < Old English burg "fort" < Proto-Germanic *burg-s < PIE *bʰr̥gʰ-s.

- Reduction of diphthong *ei to ē: theonym DEVORI, from *dēwo-rīg-ē < Proto-Celtic *deiwo-rēg-ei 'To the king of the gods'.[36]

- Lenition of *m in the group *-mnV- to -unV-:[37][38] ARIOUNIS MINCOSEGAECIS, dative form from *ar-yo-uno- *menekko-seg-āk-yo- 'To the (deities of the) fields of the many crops' < Proto-Celtic *ar-yo-mno- ... .[39]

- Assimilation *p .. kʷ > *kʷ .. kʷ: tribe name Querquerni from *kʷerkʷ- < PIE *perkʷ- 'oak, tree'.[40] Although this name has also been interpreted as Lusitanian by B. M. Prósper,[41] she proposed recently for that language a *p .. kʷ > *kʷ .. kʷ > *p .. p assimilation.[42]

- Reduction of diphthong *ew to *ow, and eventually to ō:[43] personal names TOUTONUS / TOTONUS 'of the people' from *tout- 'nation, tribe' < PIE *teut-; personal names CLOUTIUS 'famous', but VESUCLOTI 'having good fame' < Proto-Celtic *Kleut-y-os, *Wesu-kleut(-y)-os;[44] CASTELLO LOUCIOCELO < PIE *leuk- 'bright'.[45] In Celtiberian the forms toutinikum/totinikum show the same process.[46]

- Superlatives in -is(s)amo:[47] place names BERISAMO < *Berg-isamo- 'The highest one',[48] SESMACA < *Seg-isamā-kā 'The strongest one, the most victorious one'.[49] The same etymology has been proposed for the modern place names Sésamo (Culleredo) and Sísamo (Carballo), from *Segisamo-;[50] modern place name Méixamo from Magisamo- 'the largest one'.[51]

- Syncope (loss) of unstressed vowels in the vicinity of liquid consonants: CASTELLO DURBEDE, if from *dūro-bedo-.[52]

- Reduction of Proto-Celtic *χt cluster to Hispano-Celtic *t:[53] personal names AMBATUS, from Celtic *ambi-aχtos, PENTIUS < *kwenχto- 'fifth'.

Some characteristics of this language not shared by Celtiberian:

- In contact with *e or *i, intervocalic consonant *-g- tends to disappear:[43] theonym DEVORI from *dēworīgē 'To the king of the gods'; adjective derived of a place name SESMACAE < *Seg-isamā-kā 'The strongest one, the most victorious one'; personal names MEIDUENUS < *Medu-genos 'Born of mead', CATUENUS < *Katu-genos 'Born of the fight';[54] inscription NIMIDI FIDUENEARUM HIC < *widu-gen-yā.[47] But Celtiberian place name SEGISAMA and personal name mezukenos show preservation of /g/.[55]

- *-lw- and *-rw- become -lβ-, -rβ- (as in Irish):[15] MARTI TARBUCELI < *tarwo-okel- 'To Mars of the Hill of the Bull', but Celtiberian TARVODURESCA.

- Late preservation of *(-)φl- which becomes (-)βl- and only later is reduced to a simple (-)l- sound:[56][57] place names BLETISAM(AM), BLETIS(AMA), modern Ledesma (Boqueixón) < *φlet-isamā 'widest'; BLANIOBRENSI,[58] medieval Laniobre < *φlān-yo-brigs 'hillfort on the plain'.[59] But Celtiberian place name Letaisama.[60]

- *wl- is maintained:[61] VLANA < PIE *wl̥Hn-eh₂ 'wool', while Celtiberian has l-: launi < PIE *wl̥H-mn-ih₂ 'woolly' (?).

- Sometimes *wo- appears as wa-:[62] VACORIA < *(d)wo-kor-yo- 'who has two armies', VAGABROBENDAM < *uφo-gabro-bendā 'lower goat mountain' (see above).

- Dative plural ending -bo < PIE *bʰo, while Celtiberian had -bos:[57] LUGOUBU/LUCUBO 'To (the three gods) Lug'.

Gallaecian appears to be a Q-Celtic language, as evidenced by the following occurrences in local inscriptions: ARQVI, ARCVIVS, ARQVIENOBO, ARQVIENI[S], ARQVIVS, all probably from IE Paleo-Hispanic *arkʷios 'archer, bowman', retaining proto-Celtic *kʷ.[63] It is also noteworthy the ethnonyms Equaesi ( < PIE *ek̂wos 'horse'), a people from southern Gallaecia,[64] and the Querquerni ( < *perkʷ- 'oak'). Nevertheless, some old toponyms and ethnonyms, and some modern toponyms, have been interpreted as showing kw / kʷ > p: Pantiñobre (Arzúa, composite of *kʷantin-yo- '(of the) valley' and *brix-s 'hill(fort)') and Pezobre (Santiso, from *kweityo-bris),[65] ethnonym COPORI "the Bakers" from *pokwero- 'to cook',[66] old place names Pintia, in Galicia and among the Vaccei, from PIE *penkwtó- > Celtic *kwenχto- 'fifth'.[53][67]

- Some local Roman inscriptions incorporating autochthonous names, appellatives, and phrases

-

Anthropomorphic stele with Latin inscription, and local anthroponyms (from Verín, Ourense, Galicia): LATRONIUS CELTIATI F(ilius) H(ic) S(itus) E(st)

-

Stele with Latin inscription (from Mera town, Lugo, Galicia): APANA AMBOLLI F(ilia) CELTICA SVPERTAM(arica) [Castello] MIOBRI AN(norum) XXV H(ic) S(itus) E(st) APANVS FR(ater) F(aciendum) C(uravit).

-

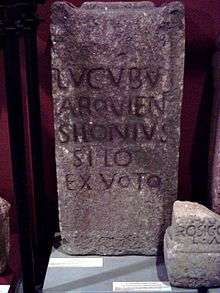

Votive inscription to Lug (from Sinagogas town, Lugo, Galicia): LUCOUBU ARQUIEN(obu) SILONIUS SILO EX VOTO

-

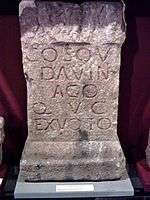

Votive inscription to the local deity Coso (from Meiras town, A Coruña, Galicia): COSOU DAVINIAGO Q(uintus) V() C() EX VOTO

-

Inscriptions in Braga, Portugal: [Ce]LICUS FRONTO ARCOBRIGENSIS AMBIMOGIDUS FECIT; and TONGOE NABIAGOI CELICUS FECIT FRONT[o]

-

Galician Latin inscription (from Lugo city, Galicia): VECIUS VEROBLII F(ilius) PRICE[ps ...] CIT(...) C(ASTELLO) CIRCINE AN(norum) LX [...]O VECI F(ilius) PRINCEPS CO[...]

See also

- Celtic place names in Galicia

- Celtiberian language

- Continental Celtic languages

- List of Galician words of Celtic origin

- Galician Institute for Celtic Studies

References

- ↑ "In the northwest of the Iberian Peninula, and more specifically between the west and north Atlantic coasts and an imaginary line running north-south and linking Oviedo and Merida, there is a corpus of Latin inscriptions with particular characteristics of its own. This corpus contains some linguistic features that are clearly Celtic and others that in our opinion are not Celtic. The former we shall group, for the moment, under the label northwestern Hispano-Celtic. The latter are the same features found in well-documented contemporary inscriptions in the region occupied by the Lusitanians, and therefore belonging to the variety known as LUSITANIAN, or more broadly as GALLO-LUSITANIAN. As we have already said, we do not consider this variety to belong to the Celtic language family." Jordán Colera 2007: p.750

- ↑ Prósper, Blanca María (2002). Lenguas y religiones prerromanas del occidente de la península ibérica. Ediciones Universidad de Salamanca. pp. 422–427. ISBN 84-7800-818-7.

- ↑ Prósper, B.M. (2005). Estudios sobre la fonética y la morfología de la lengua celtibérica in Vascos, celtas e indoeuropeos. Genes y lenguas (coauthored with Villar, Francisco). Ediciones Universidad de Salamanca, pp. 333-350. ISBN 84-7800-530-7.

- ↑ Jordán Colera 2007:p.750

- ↑ Koch, John T. (2006). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 481.

- ↑ Galician words such as crica ('vulva, ribbon'), from proto-Celtic *kīkwā ('furrow'), laxe ('stone slab') from proto-Celtic *φlagēnā ('broad spearhead'), leira ('patch, field') from proto-Celtic *φlāryo- ('floor'), and alboio ('shed, pen') from proto-Celtic *φare-bowyo- ('around-cows').

- ↑ Among them the Praestamarci, Supertamarci, Nerii, Artabri, and in general all people living by the seashore except for the Grovi of southern Galicia and northern Portugal: 'Totam Celtici colunt, sed a Durio ad flexum Grovi, fluuntque per eos Avo, Celadus, Nebis, Minius et cui oblivionis cognomen est Limia. Flexus ipse Lambriacam urbem amplexus recipit fluvios Laeron et Ullam. Partem quae prominet Praesamarchi habitant, perque eos Tamaris et Sars flumina non longe orta decurrunt, Tamaris secundum Ebora portum, Sars iuxta turrem Augusti titulo memorabilem. Cetera super Tamarici Nerique incolunt in eo tractu ultimi. Hactenus enim ad occidentem versa litora pertinent. Deinde ad septentriones toto latere terra convertitur a Celtico promunturio ad Pyrenaeum usque. Perpetua eius ora, nisi ubi modici recessus ac parva promunturia sunt, ad Cantabros paene recta est. In ea primum Artabri sunt etiamnum Celticae gentis, deinde Astyres.', Pomponius Mela, Chorographia, III.7-9.

- ↑ cf. Wodtko 2010: 355-362

- ↑ Prósper 2002: 422 and 430

- ↑ Prósper 2005: 336-338

- ↑ Prósper 2012: 53-55

- ↑ Curchin 2008: 117

- ↑ Prósper 2002: 357-358

- ↑ Prósper 2005: 282

- 1 2 Prósper 2005: 336

- ↑ Prósper 2002: 422

- ↑ Curchin 2008: 123

- ↑ Prósper 2005: 269

- ↑ Delamarre 2012: 165

- ↑ Delamarre 2012: 2011

- ↑ Vallejo 2005: 326

- ↑ Koch 2011:34

- ↑ Cf. Koch 2011: 76

- ↑ Prósper 2002: 377

- ↑ Búa 2007: 38-39

- ↑ cf. DCECH s.v. lera

- ↑ cf. DCECH s.v. llaviegu

- ↑ cf. DCECH s.v. laja

- ↑ cf. DCECH s.v. regar

- ↑ Búa 2007

- ↑ Prósper, Blanca M. "Shifting the evidence: new interpretation of Celtic and non-Celtic personal names of Western Hispania": 1. Retrieved 13 March 2014.

- ↑ Prósper 2005: 342.

- ↑ Moralejo 2010: 105

- ↑ Luján 2006: 727-729

- ↑ Prósper 2002: 357-382

- ↑ Prósper 2005: 338; Jordán Cólera 2007: 754.

- ↑ Prósper 2002: 425-426.

- ↑ Prósper 2005: 336.

- ↑ Prósper 2002: 205-215.

- ↑ Luján 2006: 724

- ↑ Prósper 2002: 397

- ↑ Prósper, B. M.; Francisco Villar (2009). "NUEVA INSCRIPCIÓN LUSITANA PROCEDENTE DE PORTALEGRE". EMERITA, Revista de Lingüística y Filología Clásica (EM). LXXVII (1): 1–32. Retrieved 11 June 2012.

- 1 2 Prósper 2002: 423.

- ↑ Prósper 2002: 211

- ↑ González García, Francisco Javier (2007). Los pueblos de la Galicia céltica. Madrid: Ediciones AKAL. p. 409. ISBN 9788446036210.

- ↑ Jordán Cólera 2007: 755

- 1 2 Wodtko 2010: 356

- ↑ Prósper 2005: 266, 278

- ↑ Prósper 2002: 423

- ↑ Prósper 2005: 282.

- ↑ Moralejo 2010: 107

- ↑ Prósper, Blanca M. "Shifting the evidence: new interpretation of Celtic and non-Celtic personal names of Western Hispania": 6–8. Retrieved 13 March 2014.

- 1 2 John T., Koch (2015). "Some Palaeohispanic Implications of the Gaulish Inscription of Rezé (Ratiatum)". Mélanges en l’honneur de Pierre-Yves Lambert: 333–46. Retrieved 16 July 2015.

- ↑ Prósper 2005: 266

- ↑ Jordán Cólera 2007: 763-764.

- ↑ Prósper 2002: 422, 427

- 1 2 Prósper 2005: 345

- ↑ Sometimes it has been read ELANIOBRENSI

- ↑ Luján 2006: 727

- ↑ Jordán Cólera 2007: 757.

- ↑ Prósper 2002: 426

- ↑ Prósper 2005: 346

- ↑ Koch, John T (2011). Tartessian 2: The Inscription of Mesas do Castelinho ro and the Verbal Complex. Preliminaries to Historical Phonology. Oxbow Books, Oxford, UK. pp. 53–54,144–145. ISBN 978-1-907029-07-3.

- ↑ Cf. Vallejo 2005: 321, who wrongly assign them to the Astures.

- ↑ Prósper 2002: 422, 378-379

- ↑ Prósper, Blanca M. "Shifting the evidence: new interpretation of Celtic and non-Celtic personal names of Western Hispania": 10. Retrieved 13 March 2014.

- ↑ de Bernardo Stempel, Patrizia (2009). "El nombre -¿céltico?- de la "Pintia vaccea"" (PDF). BSAA Arqueología: Boletín del Seminario de Estudios de Arqueología (75). Retrieved 14 March 2014.

Bibliography

- Búa, Carlos (2007) O Thesaurus Paleocallaecus, in Kremer, Dieter (ed.) (2007). Onomástica galega : con especial consideración da situación prerromana : actas do primeiro Coloquio de Trier 19 e 20 de maio de 2006. Santiago de Compostela: Universidade de Santiago de Compostela. ISBN 978-84-9750-794-3.

- Curchin, Leonard A. (2008) Estudios GallegosThe toponyms of the Roman Galicia: New Study. CUADERNOS DE ESTUDIOS GALLEGOS LV (121): 109-136.

- DCECH = Coromines, Joan (2012). Diccionario crítico etimológico castellano e hispánico. Madrid: Gredos. ISBN 978-84-249-3654-9.

- Delamarre, Xavier (2012). Noms de lieux celtiques de l'Europe ancienne (-500 / +500): dictionnaire. Arles: Errance. ISBN 978-2-87772-483-8.

- Jordán Cólera, Carlos (March 16, 2007). "Celtiberian" (PDF). e-Keltoi. 6. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- Koch, John T. (2011). Tartessian 2 : The inscription of Mesas do Castelinho ro and the verbal complex preliminaries to historical phonology. Aberystwyth: University of Wales, Centre for Advanced Welsh and Celtic Studies. ISBN 978-1-907029-07-3.

- Luján Martínez, Eugenio R. (2006) The Language(s) of the Callaeci. e-Keltoi 6: 715-748.

- Moralejo, Juan José (2010). "TOPÓNIMOS CÉLTICOS EN GALICIA" (PDF). Paleohispánica. 10. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- Prósper, Blanca María (2002). Lenguas y religiones prerromanas del occidente de la península ibérica. Ediciones Universidad de Salamanca. pp. 422–427. ISBN 84-7800-818-7.

- Prósper, Blanca María and Francisco Villar (2005). Vascos, Celtas e Indoeuropeos: Genes y lenguas. Ediciones Universidad de Salamanca. ISBN 978-84-7800-530-7.

- Prósper, Blanca María (2012). "Indo-European Divinities that Protected Livestock and the Persistence of Cross-Linguistic Semantic Paradigms: Dea Oipaingia". The Journal of Indo-European Studies. 40 (1-2): 46–58. Retrieved 25 February 2013.

- Vallejo Ruiz, José María (2005). Antroponimia indígena de la Lusitania romana. Vitoria-Gasteiz: Univ. del País Vasco [u.a.] ISBN 8483737469.

- Wodtko, Dagmar S. (2010) The Problem of Lusitanian, in Cunliffe, Barry, and John T. Koch (eds.) (2010). Celtic from the West. Oxford, UK: Oxbow books. ISBN 978-1-84217-475-3.