Gatchina

| Gatchina (English) Гатчина (Russian) | |

|---|---|

| - Town[1] - | |

Roshchinskaya Street in Gatchina | |

.svg.png) Location of Leningrad Oblast in Russia | |

Gatchina | |

|

| |

.svg.png) |

|

|

| |

| Town Day | Third Saturday of September[2] |

| Administrative status (as of June 2013) | |

| Country | Russia |

| Federal subject | Leningrad Oblast[1] |

| Administrative district | Gatchinsky District[1] |

| Settlement municipal formation | Gatchinskoye Settlement Municipal Formation[1] |

| Administrative center of | Gatchinsky District,[1] Gatchinskoye Settlement Municipal Formation[1] |

| Municipal status (as of May 2010) | |

| Municipal district | Gatchinsky Municipal District[3] |

| Urban settlement | Gatchinskoye Urban Settlement[3] |

| Administrative center of | Gatchinsky Municipal District,[4] Gatchinskoye Urban Settlement[3] |

| Statistics | |

| Population (2010 Census) | 92,937 inhabitants[5] |

| - Rank in 2010 | 184th |

| Time zone | MSK (UTC+03:00)[6] |

| First mentioned | 1499[7] |

| Town status since | 1796[7] |

| Previous names |

Khotchino,[7] Gatchina (until February 14, 1923),[8] Trotsk (until August 2, 1929),[9] Krasnogvardeysk (until January 28, 1944)[9] |

| Postal code(s)[10] | 188300-188310, 188319, 188399 |

| Dialing code(s) | +7 81371[11] |

|

| |

| Gatchina on Wikimedia Commons | |

Gatchina (Russian: Га́тчина) is a town and the administrative center of Gatchinsky District in Leningrad Oblast, Russia, located 45 kilometers (28 mi) south of St. Petersburg by the road leading to Pskov. Population: 92,937 (2010 Census);[5] 88,420 (2002 Census);[12] 79,714 (1989 Census).[13]

It is a part of the World Heritage Site Saint Petersburg and Related Groups of Monuments.[14]

Early history

Khotchino (old name of Gatchina) was first documented in 1499 as a village in possession of Novgorod the Great.[7] In the 17th century, in a series of wars, it passed to Livonia, then to Sweden, and was returned to Russia during the Great Northern War.[7] At that time, Gatchina was a southern vicinity of the new Russian capital, St. Petersburg. In 1708, Gatchina was given by Peter the Great to his sister Natalya Alexeyevna, and after her death, Peter founded an Imperial Hospital and Apothecary here.[15] In 1765, it became the property of Count Orlov.[7] Between 1766 and 1788, Count Orlov built a sombre castle with 600 rooms [16] and laid out an extensive English landscape park over 7 square kilometers (2.7 sq mi), with an adjacent zoo and a horse farm. A triumphal arch was erected to a design by the architect of Gatchina, Antonio Rinaldi (1771, built 1777-1782), forming a monumental entrance.

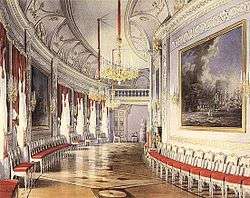

Gatchina Palace was expanded several times by several imperial owners. Rococo interiors were designed by Rinaldi and Vincenzo Brenna and executed by Italian stuccoworkers and Russian craftsmen. Interiors were highlighted with parquetry floors, painted ceilings, and distinctly Italian furniture.[17]

Imperial residence

Catherine the Great took such a great liking to the Gatchina Palace and park that at Orlov's death in 1783 she bought Gatchina and granted it to her son, the Grand Duke Paul (the future Emperor Paul I).[7] Paul I remained the owner of Gatchina for eighteen years.[7] He invested many resources as well as using his experience from his travels around Europe to make Gatchina an exemplary town and residence. During the 1790s Paul expanded and rebuilt much of the palace and renovated palatial interiors in the sumptuous Neoclassical style (illustration, left). Paul graced the park with numerous additions, bridges, gates, and pavilions, such as "The Isle of Love", "The Private garden", "The Holland garden", and "The Labyrinth", among many other additions. In November 1796, following the death of his mother, Catherine the Great, Paul became Emperor Paul I of Russia, and granted Gatchina the status of the Imperial City—an official residence of the Russian Emperors.

A remarkable monument of Paul's reign is the Priory Palace on the shore of the Black Lake. Constructed for the Russian Grand Priory of the Order of St John, it was presented to the Order by a decree of Paul I dated August 23, 1799.

After Paul's death his widow, Maria Fyodorovna owned the grand palace and park from 1801 to 1828.[7] Then Emperor Nicholas I took over ownership from 1828 to 1855. He made the most significant expansion of the palaces and parks, adding the Arsenal Halls to the main palace. The Arsenal Halls served as the summer residence of Tsar Nicholas I and his court. In 1851, Tsar Nicholas I opened the monument to his father, Paul I, in front of the Gatchina Palace. In 1853 the railroad between St. Petersburg and Gatchina opened.[7] At that time, Gatchina's territory was expanded by incorporation of several villages and vicinity.

Tsar Alexander II used Gatchina Palace as his second residence. He built a hunting village and other additions for his Imperial Hunting Crew and turned the areas south of Gatchina into his retreat, where the Tsar and his guests could indulge in living country-style among unspoiled the wilderness and woods of north-western Russia. Alexander II made updates and renovations in the Main Gatchina Palace. Tsar Alexander III, after experiencing the shock and stress of his father's assassination, made Gatchina his prime residence. The palace became known as "The Citadel of Autocracy" after the Tsar's reactionary policies. He lived most of his time in Gatchina Palace. During his reign, Alexander III introduced major technological modernization in the Gatchina Palace and parks, such as electric lights, telephone network, non-freezing water pipes, and a modern sewage system.

Nicholas II, the last Russian Tsar, spent his youth in the Gatchina Palace. His mother, the Dowager Empress Maria Fyodorovna, widow of Alexander III, was the patron of the city of Gatchina and Gatchina Palace and parks.

An erotic cabinet, ordered by Catherine the Great, seems to have been adjacent to her suite of rooms in Gatchina. The furniture was highly eccentric, with tables that had large penises for legs. The walls were covered in erotic art. There are photographs of this room and a Russian eye-witness has described the interior but the Russian authorities have always been very secretive about this peculiar Tsarist heritage. The rooms and the furniture were seen by two Wehrmacht-officers but they seem to have vanished since then.[18][19] A documentary by Peter Woditsch suggests that the cabinet was in the Peterhof Palace and not in Gatchina.[20]

20th century

Gatchina was honored as the best-kept city of Russia at the 1900 World's Fair in Paris (Exposition Universelle). The quality of life, education, medical services, and public safety in Gatchina were recognized as the best, and it was recommended as an example for other cities in Russia.

One of the first airfields in Russia was established in Gatchina in 1910.[7] The pilot Pyotr Nesterov was trained at Gatchina airfield and made his first long-distance flight from Gatchina to Kiev in the 1900s. At that time, an aviation industry was developing in Gatchina, eventually becoming one of the first centers of aviation and engine technology in Russia.

During the 1900s, Gatchina remained one of the official Imperial Residences of Tsar Nicholas II, who was presiding over annual military parades and celebrations of the Imperial Russian Army garrisons, stationed in Gatchina until 1917.

During World War I, major medical hospitals in Gatchina were patronized by the Tsar Nicholas II and Empress Maria Fyodorovna, the mother of Nicholas II, his wife the Empress Alexandra Fyodorovna, as well as their daughters: the Grand Duchess Olga, the Grand Duchess Tatiana, the Grand Duchess Maria, and the Grand Duchess Anastasia.

In May 1918, in the former imperial palace, one of the first museums in the country was opened "for the victorious popular masses of the Russian Revolution".[21] From 1918 to 1941, the Gatchina Palace and parks were open to public as a national museum.

On February 14, 1923, the town was renamed Trotsk (Троцк),[8] after Leon Trotsky. After Stalin became General Secretary of the Communist Party and Trotsky was exiled, the town was renamed Krasnogvardeysk (Красногварде́йск; lit. the Red Guard City) on August 2, 1929.[9] During the German occupation, which lasted from September 13, 1941 to January 26, 1944, the town was known as Lindemannstadt, after the Wehrmacht general Georg Lindemann.[22] The original name was returned on January 28, 1944[9] and the town has been called Gatchina ever since.

The Nazi Germans looted much of the Gatchina palace collections of art, while occupying the palace for almost three years during World War II. The Gatchina Palace and park was severely burnt, vandalized, and destroyed by the retreating Germans. The extent of devastation was extraordinary and initially was considered irreparable damage. Restoration works continued for over 60 years after the war. Some pieces of the art collection were recovered after the war and returned to Gatchina. One section of the Gatchina Palace is partially completed and certain state rooms and the Arsenal Halls are now open to the public. Other areas of the Palace, including those of Tsar Alexander III, remain closed and unrestored.

Administrative and municipal divisions

Within the framework of administrative divisions, Gatchina serves as the administrative center of Gatchinsky District.[1] As an administrative division, it is incorporated within Gatchinsky District as Gatchinskoye Settlement Municipal Formation.[1] As a municipal division, Gatchinskoye Settlement Municipal Formation is incorporated within Gatchinsky Municipal District as Gatchinskoye Urban Settlement.[3]

Economy

Industry

In Gatchina, there are several enterprises related to timber industry, including a paper mill, and to food industry.[23]

Transportation

Gatchina is an important railway node. One railway, running north to south, connects the Baltiysky railway station in St. Petersburg with Dno and Nevel. Within the town limits, suburban trains in this direction stop at the platform of Tatyanino and the station of Gatchina-Varshavskaya. Another railway, also from the Baltiysky railway station, arrives to Gatchina from the northwest and has two stops, Mariyenburg and Gatchina-Passazhirskaya-Baltiyskaya. Yet another railway runs south of the town center from east to west and connects Mga via Ulyanovka with Volosovo. The railway station on this line in Gatchina is Gatchina-Tovarnaya-Baltiyskaya.

The M20 Highway connecting St. Petersburg and Pskov, crosses Gatchina from north to south. South of Gatchina, it crosses the A120 Highway, which encircles St. Petersburg. A paved road connects Gatchina with Kingisepp via Volosovo. There are also local roads.

Science

Gatchina is the site of the Petersburg Nuclear Physics Institute.[24]

Twin cities

References

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Oblast Law #32-oz

- ↑ Гатчина готовится к Дню города (in Russian). Администрация МО «Город Гатчина». Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Law #115-oz

- ↑ Law #113-oz

- 1 2 Russian Federal State Statistics Service (2011). "Всероссийская перепись населения 2010 года. Том 1" [2010 All-Russian Population Census, vol. 1]. Всероссийская перепись населения 2010 года (2010 All-Russia Population Census) (in Russian). Federal State Statistics Service. Retrieved June 29, 2012.

- ↑ Правительство Российской Федерации. Федеральный закон №107-ФЗ от 3 июня 2011 г. «Об исчислении времени», в ред. Федерального закона №271-ФЗ от 03 июля 2016 г. «О внесении изменений в Федеральный закон "Об исчислении времени"». Вступил в силу по истечении шестидесяти дней после дня официального опубликования (6 августа 2011 г.). Опубликован: "Российская газета", №120, 6 июня 2011 г. (Government of the Russian Federation. Federal Law #107-FZ of June 31, 2011 On Calculating Time, as amended by the Federal Law #271-FZ of July 03, 2016 On Amending Federal Law "On Calculating Time". Effective as of after sixty days following the day of the official publication.).

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Энциклопедия Города России. Moscow: Большая Российская Энциклопедия. 2003. p. 104. ISBN 5-7107-7399-9.

- 1 2 Гатчинский уезд (февраль 1923 г. - август 1927 г.) (in Russian). Система классификаторов исполнительных органов государственной власти Санкт-Петербурга. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Троцкий район (август 1927 г. - август 1929 г.), Красногвардейский район (август 1929 г. - январь 1944 г.), Гатчинский район (январь 1944 г.) (in Russian). Система классификаторов исполнительных органов государственной власти Санкт-Петербурга. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ↑ Почта России. Информационно-вычислительный центр ОАСУ РПО. (Russian Post). Поиск объектов почтовой связи (Postal Objects Search) (Russian)

- ↑ Гатчина и Гатчинский район Справочная информация (in Russian). gatchina.biz. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ↑ Russian Federal State Statistics Service (May 21, 2004). "Численность населения России, субъектов Российской Федерации в составе федеральных округов, районов, городских поселений, сельских населённых пунктов – районных центров и сельских населённых пунктов с населением 3 тысячи и более человек" [Population of Russia, Its Federal Districts, Federal Subjects, Districts, Urban Localities, Rural Localities—Administrative Centers, and Rural Localities with Population of Over 3,000] (XLS). Всероссийская перепись населения 2002 года [All-Russia Population Census of 2002] (in Russian). Retrieved August 9, 2014.

- ↑ Demoscope Weekly (1989). "Всесоюзная перепись населения 1989 г. Численность наличного населения союзных и автономных республик, автономных областей и округов, краёв, областей, районов, городских поселений и сёл-райцентров" [All Union Population Census of 1989: Present Population of Union and Autonomous Republics, Autonomous Oblasts and Okrugs, Krais, Oblasts, Districts, Urban Settlements, and Villages Serving as District Administrative Centers]. Всесоюзная перепись населения 1989 года [All-Union Population Census of 1989] (in Russian). Институт демографии Национального исследовательского университета: Высшая школа экономики [Institute of Demography at the National Research University: Higher School of Economics]. Retrieved August 9, 2014.

- ↑ UNESCO World Heritage Centre. "Historic Centre of Saint Petersburg and Related Groups of Monuments". unesco.org. Retrieved November 6, 2015.

- ↑ Peter the Great: His Life and World (Knopf, 1980) by Robert K. Massie, ISBN 0-394-50032-6 (also Wings Books, 1991, ISBN 0-517-06483-9)

- ↑ photo

- ↑ St. Petersburg: Architecture of the Tsars. Abbeville Press, 1996. ISBN 0-7892-0217-4

- ↑ Igorʹ Semenovich Kon and James Riordan, Sex and Russian Society page 18.

- ↑ http://www.trouw.nl/tr/nl/4512/Cultuur/archief/article/detail/1775415/2003/12/06/Het-Geheim-van-Catherina-de-Grote.dhtml Article in Trouw by Peter Dekkers. Retrieved 8 july 2014

- ↑ http://www.deproductie.nl/films/het-geheim-van-catherina-de-grote/ Trailer of the documentary by Peter Woditsch. Retrieved 8 july 2014

- ↑ (Russian) Гатчинский дворец, годы испытаний

- ↑ Max Schafer (2011), Jahrgang 1924, p. 44 ISBN 3-8423-1113-3

- ↑ Комитет экономики и инвестиций (in Russian). Гатчинский муниципальный район. Retrieved February 7, 2013.

- ↑ "Petersburg Nuclear Physics Institute. National Research Centre "Kurchatov Institute"". pnpi.spb.ru. Retrieved November 6, 2015.

Sources

- Законодательное собрание Ленинградской области. Областной закон №32-оз от 15 июня 2010 г. «Об административно-территориальном устройстве Ленинградской области и порядке его изменения», в ред. Областного закона №23-оз от 8 мая 2014 г. «Об объединении муниципальных образований "Приморское городское поселение" Выборгского района Ленинградской области и "Глебычевское сельское поселение" Выборгского района Ленинградской области и о внесении изменений в отдельные Областные законы». Вступил в силу со дня официального опубликования. Опубликован: "Вести", №112, 23 июня 2010 г. (Legislative Assembly of Leningrad Oblast. Oblast Law #32-oz of June 15, 2010 On the Administrative-Territorial Structure of Leningrad Oblast and on the Procedures for Its Change, as amended by the Oblast Law #23-oz of May 8, 2014 On Merging the Municipal Formations of "Primorskoye Urban Settlement" in Vyborgsky District of Leningrad Oblast and "Glebychevskoye Rural Settlement" in Vyborgsky District of Leningrad Oblast and on Amending Various Oblast Laws. Effective as of the day of the official publication.).

- Законодательное собрание Ленинградской области. Областной закон №113-оз от 16 декабря 2004 г. «Об установлении границ и наделении соответствующим статусом муниципального образования Гатчинский муниципальный район и муниципальных образований в его составе», в ред. Областного закона №17-оз от 6 мая 2010 г «О внесении изменений в некоторые областные законы в связи с принятием федерального закона "О внесении изменений в отдельные законодательные акты Российской Федерации в связи с совершенствованием организации местного самоуправления"». Вступил в силу через 10 дней со дня официального опубликования (27 декабря 2004 г.). Опубликован: "Вести", №147, 17 декабря 2004 г. (Legislative Assembly of Leningrad Oblast. Oblast Law #113-oz of December 16, 2004 On Establishing the Borders of and Granting an Appropriate Status to the Municipal Formation of Gatchinsky Municipal District and to the Municipal Formations It Comprises, as amended by the Oblast Law #17-oz of May 6, 2010 On Amending Various Oblast Laws Due to the Adoption of the Federal Law "On Amending Various Legislative Acts of the Russian Federation Due to the Improvement of the Organization of the Local Self-Government". Effective as of after 10 days from the day of the official publication (December 27, 2004).).

- Законодательное собрание Ленинградской области. Областной закон №115-оз от 22 декабря 2004 г. «Об установлении границ и наделении статусом городского поселения муниципального образования город Гатчина в Гатчинском муниципальном районе», в ред. Областного закона №43-оз от 27 июня 2013 г. «О присоединении деревни Большая Загвоздка к городу Гатчина и о внесении изменений в некоторые Областные законы в сфере административно-территориального устройства Ленинградской области». Вступил в силу через 10 дней со дня официального опубликования (2 января 2005 г.). Опубликован: "Вести", №149, 23 декабря 2004 г. (Legislative Assembly of Leningrad Oblast. Oblast Law #115-oz of December 22, 2004 On Establishing the Borders of and Granting Urban Settlement Status to the Municipal Formation of the Town of Gatchina in Gatchinsky Municipal District, as amended by the Oblast Law #43-oz of June 27, 2013 On Merging the Village of Bolshaya Zagvozdka into the Town of Gatchina and on Amending Various Oblast Laws on the Subject of the Administrative-Territorial Structure of Leningrad Oblast. Effective as of after 10 days from the day of the official publication (January 2, 2005).).

Further reading

- St. Petersburg: Architecture of the Tsars. Abbeville Press, 1996. ISBN 0789202174

- Knopf Guide: St. Petersburg. New York: Knopf, 1995. ISBN 0-679-76202-7

- Glantz, David M. The Battle for Leningrad, 1941-1944. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2002. ISBN 0-7006-1208-4

- Radzinsky, Edvard. Alexander II: The Last Great Tsar. New York: The Free Press, 2005. ISBN 0-7432-7332-X

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gatchina. |

- Official website of Gatchina (Russian)

- Art monuments & History of former residence of the Russian Emperors

- Gatchina over the Centuries (Russian)

- Views of Gatchina Park

- Gatchina Humanitarian Portal (Russian)