Goethe–Schiller Monument (Syracuse)

| German: Goethe und Schiller | |

| |

| Artist | Ernst Rietschel |

|---|---|

| Year | 1911 |

| Type |

copper electrotyping (from original 1857 bronze in Weimar) |

| Location | Syracuse |

| 43°4′10.5″N 76°8′30″W / 43.069583°N 76.14167°WCoordinates: 43°4′10.5″N 76°8′30″W / 43.069583°N 76.14167°W | |

The Goethe–Schiller Monument in Syracuse, New York incorporates a copper double-statue of the German poets Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832) and Friedrich Schiller (1759–1805). It was erected by the German-American organizations of Syracuse and Onondaga County, and was unveiled on October 15, 1911.[1] Schiller, who is on the reader's right in the photograph, was called the "poet of freedom" in the US, and he had an enormous 19th Century following.[2][3][4][5] The Syracuse monument was the last of 13 monuments to Schiller that were erected in US cities.[6][7][8] Goethe was the "supreme genius of modern German literature";[9] he and Schiller are paired in the statue because they had a friendship "like no other known to literature or art."[10] As Paul Zanker writes, in the statue a "fatherly Goethe gently lays his hand on the shoulder of the restless Schiller, as if to quiet the overzealous passion for freedom of the younger generation."[4] Goethe is holding a laurel wreath in his right hand, and Schiller's right hand is reaching towards it.

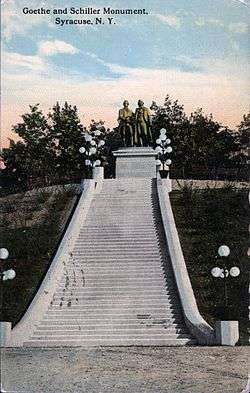

The Goethe–Schiller Monument in Syracuse was modeled on the 1857 monument in Weimar, Germany. Ernst Rietschel had been commissioned to create a cast bronze double-statue for Weimar, which was exactly copied for the Syracuse and for three earlier US monuments. The Syracuse monument is in Schiller Park, which had been renamed in 1905, the centennial of Schiller's death.[11] The statue tops a large black marble pedestal; it is at the top of a steep slope, and is approached by a formal stairway (see postcard and photo).

The US monuments were costly and took years of fundraising and effort to erect. Their dedications drew large crowds. The 1907 dedication of the Goethe–Schiller monument in Cleveland, Ohio drew 65,000 attendees.[12] For the dedication in Syracuse, The Syracuse Herald reported that:[1]

Impressive ceremonies marked the unveiling of the Schiller–Goethe monument in Schiller park yesterday afternoon. Thousands of German citizens of Syracuse and thousands of others who appreciate the gift German residents have made to the city were present when Miss Lulu E. Dopffel pulled the cord that released the flags and exposed the beautiful memorial to view.

It was a scene long to be remembered. The plateau of Schiller park, rising high above its surroundings and topped with the bronze figures of the German poets, was thronged with men and women and children. Hundreds were there who had never visited Schiller park. Scores of banners of the marching societies, American flags and brilliant uniforms added to the beauty of the scene.

19th century context

As Paul Zanker describes it, the original Weimar monument helped launch a "veritable cult" of zeal for the poets and of monument building.[4] The monument was very unusual for its time. It was rare until the 1850s to erect costly monuments to poets and intellectuals. Double monuments were also unusual, as was the choice to depict the poets in contemporary dress. The resulting monument was considered highly successful,[4] and set a style for the numerous monuments to the poets that followed. By 1859, the centenary of Schiller's birth and the occasion for 440 celebrations in German lands, Schiller in particular had emerged as the "poet of freedom and unity" for German citizens. Rüdiger Görner has illustrated the origins of Schiller's reputation with a speech from the "famous" tenth scene of the third act of Schiller's 1787 play, Don Carlos: "Look all around at nature's mastery, / Founded on freedom. And how rich it grows, / Feeding on freedom."[13] Ute Frevert has written of the celebrations,[14] "It did not matter who spoke, a Hamburg plumber, a political emigrant in Paris, an aristocratic civil servant in Münster, a writer in Wollenbüttel, they unanimously invoked Schiller as a singer of freedom and the prophet of German unity."

About four dozen monuments to Schiller or Goethe were erected in German-speaking Europe between 1850 and the outbreak of World War I in 1914.[15] In the same era, four million German-speakers emigrated to the United States.[16] Schiller continued to have great significance to these immigrants; his work "was the best expression of that side of German character which most qualified the German despite his distinctiveness to become a true American citizen".[17] By the late 1800s, the German-Americans had also become prodigious monument builders, and they erected at least fifteen additional monuments to the poets prior to World War I.[6][15]

In 1900, the total population of Syracuse and Onondaga County was 168,000.[18] Nearly 10,000 had been born in German-speaking countries of Europe; with their children, it was estimated at the time that there were more than 25,000 German-speakers.[19] There were extensive observances in May, 1905 of the centennial of Schiller's death.[20] Round Top Park was renamed Schiller Park on July 3, 1905, and planning commenced for the Goethe–Schiller Monument.[1][11]

The monument they erected was costly. In Syracuse, the 1908 Deutscher Tag (German Day) celebration was raising funds for the monument,[21] as did the subsequent 1909 and 1910 German Days. The 1908 Goethe–Schiller Monument in Milwaukee cost $15,000 to erect,[22] and presumably the cost for the Syracuse monument three years later was about the same. For comparison, the cost of building the sizable 1901 Deutsche Evangelische Friedenskirche (German Evangelist Peace Church) in Syracuse was also about $15,000.[23]

Ultimately, about 60 monuments to Schiller and to Goethe were built in German-speaking Europe and the United States.[6][15][24] The 1911 Syracuse monument was one of the last in the style that had been largely established by the Weimar original 54 years earlier. Christiane Hertel has suggested that the lavishness of the late monuments and their celebrations in the US were "a German-American farewell to the Schiller cult, at least in this form and with this popular, inclusive scope."[5] While the Weimar monument is still "one of the most famous and most beloved monuments in all of Germany",[6] the original significance of the US monuments is now largely forgotten.[25]

Fabrication and restoration of the monument

The first three Goethe–Schiller monuments in the US were in San Francisco (1901), Cleveland (1907), and Milwaukee (1908). They all incorporated bronze sculptures cast at the foundry in Lauchhammer, Germany;[7][26] the original sculpture in Weimar is also a bronze casting. The statue in Syracuse is not a casting; it consists of thin copper pieces that are joined together.[27] The statue has a small plaque attached to its base that reads "Galvanoplastik-Geislingen St.",[28] which indicates that it was made by the Abteilung für Galvanoplastik (Galvanoplastic Division) of the WMF Company in Geislingen an der Steige, Germany. Galvanoplastik is a German word encompassing both electrotyping and electroforming.[29][30] The pieces were fabricated using the electrotyping process, which involves the depositing of copper metal from a solution of chemicals onto the inside of a mold. The process is activated by electrical currents flowing between wires immersed in the solution and a coating on the mold; the coating and the solution both conduct electricity.[31] As in the Syracuse statue, large electrotyped sculptures typically consist of electrotyped copper pieces that are joined together, most likely by soldering.[27][32] The individual pieces in electrotyped sculptures are a fraction of an inch thick, and one surface conforms very exactly to the details of the mold. The Syracuse sculpture is apparently the only copy of Rietschel's statue that was produced using copper electrotyping, and may be the only public artwork in the United States that was produced by WMF.[33]

As can be seen by comparing the 1913 postcard and the contemporary photograph, at some point the decorative electrical lighting fixtures on the staircase leading to the monument were removed. By 2001 the condition of the monument had become very poor due both to weathering and to vandalism.[34] The German-American Society of Central New York undertook a project to restore the monument, in cooperation with the city government of Syracuse.[35] In 2003, the statue was restored by Sharon BuMann,[36] who described the construction of the statue in an interview the same year.[27] At the same time the masonry pedestal for the statue was cleaned, the stairway leading to the statue was repaired, and decorative iron fencing was installed around the statue and pedestal.[27]

References

- 1 2 3 "Poets Are Honored; Thousands See Unveiling Ceremony at Schiller-Goethe Monument". The Syracuse Herald. Syracuse. October 16, 1911. Online version posted by Michelle Stone.

- ↑ There are many 19th Century references to Schiller as the "poet of freedom". One example: "Schiller". The Literary World. Boston: S.R. Crocker. 15: 228. July 12, 1884.

Schiller's title to special regard in this country and throughout the English-speaking world rests, moreover, on the fact that he is in a special sense the poet of freedom. No poet of the last hundred years has been a more impassionled lover of liberty, political and social, intellectual and moral, than was the author of Wallenstein and William Tell.

- ↑ Billington, Michael (29 January 2005). "The German Shakespeare:Schiller used to be box-office poison. Why are his plays suddenly back in favour, asks Michael Billington". The Guardian.

- 1 2 3 4 Zanker, Paul (1996). The Mask of Socrates: The Image of the Intellectual in Antiquity. Alan Shapiro (Trans.). University of California Press. pp. 3–6. ISBN 978-0-520-20105-7.

There arose a true cult of the monument ... the Germans began to see themselves, faute de mieux, as "the people of poets and thinkers." ... This is especially true of the period of the restoration, and in particular, the years after the failed revolution of 1848, when monuments to famous Germans, above all Friedrich von Schiller, sprouted everywhere. ... The great men were deliberately rendered not in ancient costume, and certainly not nude, but in contemporary dress and exemplary pose.

Translation of Die Maske des Sokrates. Das Bild des Intellektuellen in der Antiken Kunst. C. H. Beck. 1995. ISBN 3-406-39080-3.

Perhaps the most famous of those monuments — and the one considered most successful by people of the time — was the group of Goethe and Schiller by Ernst Rietschel, set up in 1857 in front of the theater in Weimar. A fatherly Goethe gently lays his hand on the shoulder of the restless Schiller, as if to quiet the overzealous passion for freedom of the younger generation. - 1 2 Hertel, Christiane (2003). "The Nineteenth-Century Schiller Cult: Centennials, Monuments, and Tableaux Vivants". Yearbook of German-American Studies. 38: 155–204.

The Schiller cult generally lessened toward the end of the nineteenth century and this development, too, is worthy of comparative attention. Here the differences between the German and German-American perspectives manifest themselves in a temporal delay. While in 1905 and 1907 German-Americans in Chicago and Cleveland engaged in yet another elaborate homage to Schiller, it appears that in Germany the popular simplified image of Schiller as "Nationaldichter" was already eroding in the late 1870s and 1880s. There were few important sculpture commissions, for example. This is in contrast to the United States. And yet there is something about the very sumptuousness of the 1905 and 1907 celebrations that suggests a grand finale and thus also a German-American farewell to the Schiller cult, at least in this form and with this popular, inclusive scope.

Not available online. - 1 2 3 4 Pohlsander, Hans A. (2010). German monuments in the Americas: bonds across the Atlantic. Peter Lang. p. 84. ISBN 978-3-0343-0138-1.

The city of Weimar boasts one of the most famous and most beloved monuments in all of Germany, the Goethe–Schiller monument in front of the Nationaltheater.

- 1 2 The Smithsonian Institution lists twelve public monuments to Schiller; they are in New York (1859), Philadelphia (1886), Chicago (1886), Columbus (1891), St. Louis (1898), San Francisco (1901), Cleveland (1907), St. Paul (1907), Rochester (1907), Detroit (1908), Milwaukee (1908), and Syracuse (1911). See "Search Results for Schiller Johann Christoph Friedrich von". Smithsonian Institution Collections Search Center. Retrieved August 14, 2011.

- ↑ Beyond the 12 US monuments to Schiller listed by the Smithsonian, a thirteenth monument was built in Omaha in 1905. See Federal Writers' Project; Boye, Alan (2005). Nebraska: a guide to the Cornhusker State. University of Nebraska Press. p. 252. ISBN 978-0-8032-6918-7.

RIVERVIEW PARK, ... A MONUMENT TO SCHILLER, designed by Johannes Maihoefer, shows the poet holding a book in his left hand and a pen in the right. The figure, about four feet tall, is mounted on a granite pedestal of four and one half feet, which, in turn, stands on a wide base formed in three low steps. On the front of the pedestal is a bronze lyre within a laurel wreath. The monument stands on a crest in the park, commanding a view of the area. In 1917, stimulated by World War propaganda, vandals attempted to destroy the monument because it was in honor of a German. After the war, the stone was restored. The Omaha Schwaben Society and other citizens of German birth or descent erected the monument in 1905.

This book is a reprinting of the 1939 original. - ↑ Boyle, Nicholas (1986). Goethe, Faust, Part 1. Cambridge University Press. p. 1. ISBN 0-521-31412-7.

Goethe is the supreme genius of modern German literature, and the dominant influence on German literary culture since the middle of the eighteenth Century.

- ↑ Steiner, George (30 January 2000). "More than just an old Romantic: The second volume of Nicholas Boyle's impressive life of Goethe covers thirteen years in 949 pages". The Guardian.

The Goethe–Schiller nexus, beginning in July 1794, the collaborative rivalry and loving tension between the two men in Jena and Weimar, is like no other known to literature or art. No single thread can do justice to the intricacies of Goethe's inner evolution during these seminal years. But Boyle does trace the change in Goethe from an earlier Romantic radicalism, from a Promethean rebelliousness, to that Olympian conservatism which was to become his hallmark. A deep sense of domesticity, of familial pleasures, of emotional balance took over in 1793 and 1794 from the Sturm und Drang of an earlier sensibility.

- 1 2 "Round Top is Schiller Park". The Post-Standard. Syracuse, New York. July 4, 1905. Paid online access.

- ↑ Rowan, Steven W., ed. (1998). Cleveland and its Germans (1907 Edition). Western Reserve Historical Society Publication No. 185. Western Reserve Historical Society. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-911704-50-1. Translation from the German of Cleveland und Sein Deutschtum. Cleveland, Ohio: German-American Biographical Pub. Co. 1907.

- ↑ Görner, Rüdiger (November 2009). "Schiller's Poetics of Freedom". Standpoint.

Look all around at nature's mastery, / Founded on freedom. And how rich it grows, / Feeding on freedom.

In the quote, the Marquis de Posa is imploring Philip II, the King of Spain. The original German text is: Sehen Sie sich um / In seiner herrlichen Natur! Auf Freiheit / Ist sie gegründet - und wie reich ist sie / Durch Freiheit! See Schiller, Friedrich (1907). Schillers Don Karlos, Infant von Spanien. Ein dramatisches Gedicht. Paderborn: Ferdinand Schöningh. p. 151. See also "Prof Rüdiger Görner". Queen Mary University of London. - ↑ Frevert, Ute (2007). "A Poet for Many German Nations". In Kerry, Paul E. Friedrich Schiller: playwright, poet, philosopher, historian. Peter Lang. p. 311. ISBN 978-3-03910-307-2.

- 1 2 3 24 monuments to Schiller were built in German-speaking parts of Europe prior to World War I, and 13 were built in the US. 22 additional monuments to Goethe were built in Europe, and two in the US. See List of Schiller Monuments and List of Goethe Monuments (in German).

- ↑ Adams, Willi Paul; Rippley, LaVerne J.; Reichmann, Eberhard (1993). The German Americans: An Ethnic Experience. Indiana University-Purdue University at Indianapolis. Translation of the book Adams, Willi Paul (1990). Die Deutschen im Schmelztiegel der USA: Erfahrungen im grössten Einwanderungsland der Europäer (in German). Die Ausländerbeauftragte des Senats von Berlin.

- ↑ Conzen, Kathleen Neils (1989). "Ethnicity as Festive Culture: Nineteenth-Century German America on Parade". In Sollors, Werner. The Invention of Ethnicity. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-505047-9.

... the freedom that Schiller celebrated was the freedom that Germans had found in America. Schiller, proclaimed a speaker at New York's celebration, was the best expression of that side of German character which most qualified the German despite his distinctiveness to become a true American citizen

- ↑ 1900 US census data for Onondaga County retrieved from "National Historical Geographical Information System". Retrieved 2011-09-14.. Login required.

- ↑ Loos, J. (March 19, 1897). "Syracuse's Foreign Born Population — Some Statistics". The Syracuse Herald. p. 28. Online version posted by Michelle Stone.

- ↑ "Large Throng Attends The Schiller Observance. Fifteen Hundred Persons at Turn Hall Listen to a Programme in Memory of the Great Poet.". The Post-Standard. May 10, 1905. Posted by Michelle Stone.

- ↑ "Editorial: German Day in Syracuse". The Syracuse Herald. August 3, 1908. Posted by Michelle Stone.

- ↑ Buck, Diane M.; Palmer, Virginia A. (1995). Outdoor Sculpture in Milwaukee: A Cultural and Historical Guidebook. The State Historical Society of Wisconsin, Madison. p. 158. ISBN 978-0-87020-276-6. Not accessible online.

- ↑ 1903 Syracuse city directory, as reported by Stone, Michelle. "German Churches". Retrieved 2011-09-09.

- ↑ Pohlsander, Hans A. (2008). National Monuments and Nationalism in 19th Century Germany. pp. 117–119. ISBN 978-3-03911-352-1. Hans A. Pohlsander is professor emeritus at the University of Albany, where he previously served as the chairman of the Department of Classics. See "Hans Pohlsander". University at Albany. Retrieved July 11, 2011.

- ↑ High, Jeffrey L. (2011). "Introduction: Why is this Schiller [Still] in the United States?". In High, Jeffrey L.; Martin, Nicholas; Oellers, Norbert. Who Is This Schiller Now?: Essays on His Reception and Significance. Camden House. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-57113-488-2.

Though Schiller's US prominence was nearly erased by the World Wars, ... artists and intellectuals remain less likely to judge a book cover by its nation of initial publication, than to read it first. As a result, Schiller never really left the US cultural scene.

- ↑ "Historische Referenzen" [Historical References] (in German). Die Kunstgießerei Lauchhammer. Retrieved 2015-04-13.

- 1 2 3 4 Case, Dick (September 3, 2003). "Park Monument Work Something to Look Up To". The Syracuse Post-Standard. p. B1. Paid online access.

- ↑ "Search Results for Goethe Schiller, sculpture". Smithsonian Institution Collections Search Center. Retrieved 2011-09-05.

- ↑ Lüer, Hermann (1902). "VIII. Die Galvanoplastik". Technik der Bronzeplastik (in German). Leipzig: Hermann Seeman Nachfolger. p. 130.

- ↑ Meißner, Birgit; Doktor, Anke (2000). "Galvanoplastik – Geschichte einer Technik aus dem 19. Jahrhundert" [Galvanoplastik - History of a Technology from the 19th Century]. In Meißner, Birgit; Doktor, Anke; Mach, Martin. Bronze- und Galvanoplastik: Geschichte – Materialanalyse – Restaurierung (PDF) (in German). Landesamt für Denkmalpflege Sachsen. pp. 127–137.

- ↑ Bassett, Jane; Fogelman, Peggy (1997). Looking at European sculpture: a guide to technical terms. Getty Publications. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-89236-291-2.

The process of using an electric current to deposit metal into a mold or negative impression of a desired form, in order to create a three-dimensional relief. A similar technique, electroforming, builds a metal shell onto a positive pattern. ... Electrotyping was developed in the mid-nineteenth century and gave rise to the mass production of affordable works of art and decoration for the general public.

- ↑ Scott, David A. (2002). Copper and bronze in art: corrosion, colorants, conservation. Getty Publications. ISBN 978-0-89236-638-5.

Large objects would be electrotyped in pieces, which were then soft-soldered together, followed by a recoating with copper to disguise the join.

- ↑ "Search Results for "Galvano Plastik" OR Galvanoplastik". Smithsonian Collections Search Center. Retrieved 2011-10-15.

- ↑ English, Molly (May 2, 2001). "Monumental Stupidity: Syracuse's once-glorious statues now stand as testaments to neglect.". Syracuse New Times.

- ↑ "Goethe und Schiller Monument". German-American Society of Central New York. Retrieved 2015-04-13.

- ↑ "Sharon BuMann - Technical Restoration Services". Retrieved 2013-08-21.

Further reading

- Adamova, Mila. "Rezeption Schillers (und besonders der "Räuber") in den USA." (in German).

- Haber, Georg J.; Heimler, Maximilian (1994). "Kupfergalvanoplastik: Geschichte, Herstellungstechniken und Restarierungproblematik kunst-industrieller Katalogware" [Copper Electrotyping: History, Fabrication Technology, and Restoration Problems of Art-industry Catalogwares]. In Heinrich, Peter; Syndram, Dirk. Metallrestaurierung, Beiträge zur Analyse, Konzeption und Technologie (in German). Callwey. pp. 160–181. ISBN 978-3-7667-0999-8.

- Jackson, Theodore (2006). "A Struggle for Recognition: The Saint Louis Schillerverein" (PDF). Focus on German Studies. 13: 87–97.

- McMillan, Walter George (1890). A treatise on electro-metallurgy. C. Griffin and company. p. 178.