Golden spike

Coordinates: 41°37′4.67″N 112°33′5.87″W / 41.6179639°N 112.5516306°W

The golden spike (also known as The Last Spike[1]) is the ceremonial final spike driven by Leland Stanford to join the rails of the First Transcontinental Railroad across the United States connecting the Central Pacific and Union Pacific railroads on May 10, 1869, at Promontory Summit, Utah Territory. The term last spike has been used to refer to one driven at the usually ceremonial completion of any new railroad construction projects, particularly those in which construction is undertaken from two disparate origins towards a meeting point. The spike now lies in the Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University.[2]

History

Completing the last link in the transcontinental railroad with a spike of gold was the brainchild of David Hewes, a San Francisco financier and contractor.[3] The spike had been manufactured earlier that year especially for the event by the William T. Garratt Foundry in San Francisco. Two of the sides were engraved with the names of the railroad officers and directors.[3] A special tie of polished California laurel was chosen to complete the line where the spike would be driven.[3] The ceremony was originally to be held on May 8, 1869 (the date actually engraved on the spike), but it was postponed two days because of bad weather and a labor dispute that delayed the arrival of the Union Pacific side of the rail line.[3]

On May 10, in anticipation of the ceremony, Union Pacific No. 119 and Central Pacific No. 60 (better known as the Jupiter) locomotives were drawn up face-to-face on Promontory Summit.[4] It is unknown how many people attended the event; estimates run from as low as 500 to as many as 3,000; government and railroad officials and track workers were present to witness the event.[3]

Before the last spike was driven, three other commemorative spikes, presented on behalf of the other three members of the Central Pacific's Big Four who did not attend the ceremony, had been driven in the pre-bored laurel tie:

- a second, lower-quality gold spike, supplied by the San Francisco News Letter was made of $200 worth of gold and inscribed: With this spike the San Francisco News Letter offers its homage to the great work which has joined the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans.

- a silver spike, supplied by the State of Nevada; forged, rather than cast, of 25 troy ounces (780 g) of unpolished silver.

- a blended iron, silver and gold spike, supplied by the Arizona Territory, engraved: Ribbed with iron clad in silver and crowned with gold Arizona presents her offering to the enterprise that has banded a continent and dictated a pathway to commerce.[5] This spike was given to Union Pacific President Oliver Ames following the ceremony. It is on display at the Union Pacific Museum in Council Bluffs, Iowa.[6]

The golden spike was made of 17.6-karat (73%) copper-alloyed gold, and weighed 14.03 troy ounces (436 g). It was dropped into a pre-drilled hole in the laurel ceremonial last tie, and gently tapped into place with a silver ceremonial spike maul. The spike was engraved on all four sides:

- The Pacific Railroad ground broken January 8, 1863, and completed May 8, 1869.

- Directors of the C. P. R. R. of Cal. Hon. Leland Stanford. C. P. Huntington. E. B. Crocker. Mark Hopkins. A. P. Stanford. E. H. Miller Jr.

- Officers. Hon. Leland Stanford. Presdt. C. P. Huntington Vice Presdt. E. B. Crocker. Atty. Mark Hopkins. Tresr. Chas Crocker Gen. Supdt. E. H. Miller Jr. Secty. S. S. Montague. Chief Engr.

- May God continue the unity of our Country, as this Railroad unites the two great Oceans of the world. Presented by David Hewes San Francisco.[3]

A second golden spike, exactly like the one from the ceremony, was cast and engraved at the same time. It was held, unknown to the public, by the Hewes family until 2005. This second spike is now on permanent display, along with Thomas Hill's famous painting The Last Spike, at the California State Railroad Museum in Sacramento.[7]

With the locomotives drawn so near, the crowd pressed so closely around Stanford and the other railroad officials that the ceremony became somewhat disorganized, leading to varying accounts of the actual events. Contrary to the myth that the Central Pacific's Chinese laborers were specifically excluded from the festivities, A.J. Russell stereoview No. 539 shows the "Chinese at Laying Last Rail UPRR". Eight Chinese laid the last rail, and three of these men, Ging Cui, Wong Fook, and Lee Shao, lived long enough to also participate in the 50th anniversary parade. At the conclusion of the ceremony, the Chinese participating were honored and cheered by the CPRR officials and that road's construction chief, J.H Strobridge, at a dinner in his private car.[8]

To drive the final spike, Stanford lifted a silver spike maul and drove the spike into the tie, completing the line. Stanford and Hewes missed the spike, but the single word "done" was nevertheless flashed by telegraph around the country. In the United States, the event has come to be considered one of the first nationwide media events. The locomotives were moved forward until their "cowcatchers" met, and photographs were taken. Immediately afterwards, the golden spike and the laurel tie were removed, lest they be stolen, and replaced with a regular iron spike and normal tie. At exactly 12:47 pm, the last iron spike was driven, finally completing the line.[3]

After the ceremony, the Golden Spike was donated to the Stanford Museum (now Cantor Arts Center) in 1898. The last laurel tie was destroyed in the fires caused by the 1906 San Francisco earthquake.[3]

A.J. Russell image of the celebration following the driving of the "Last Spike" at Promontory Summit, U.T., May 10, 1869. Because of temperance feelings the liquor bottles held in the center of the picture were removed from some later prints.

A.J. Russell image of the celebration following the driving of the "Last Spike" at Promontory Summit, U.T., May 10, 1869. Because of temperance feelings the liquor bottles held in the center of the picture were removed from some later prints. The Jupiter leads the train that carried Leland Stanford, one of the "Big Four" owners of the Central Pacific Railroad, and other railway officials to the Golden Spike Ceremony.

The Jupiter leads the train that carried Leland Stanford, one of the "Big Four" owners of the Central Pacific Railroad, and other railway officials to the Golden Spike Ceremony. May 10, 1869 Celebration of completion of the Transcontinental Railroad

May 10, 1869 Celebration of completion of the Transcontinental Railroad

Aftermath

Although the Promontory event marked the completion of the transcontinental railroad line, it did not actually mark the completion of a seamless coast-to-coast rail network: neither Sacramento nor Omaha was a seaport, nor did they have rail connections until after they were designated as the termini. The Mossdale Bridge, which was the final section across the San Joaquin River near Lathrop, California, was finally completed in September 1869 connecting Sacramento in California.[9] Passengers were required to cross the Missouri River between Council Bluffs, Iowa, and Omaha, Nebraska, by boat until the building of the Union Pacific Missouri River Bridge in 1872. In the meantime, a coast-to-coast rail link was achieved in August 1870 in Strasburg, Colorado, by the completion of the Denver extension of the Kansas Pacific Railway.[10]

In 1904 a new railroad route called the Lucin Cutoff was built by-passing the Promontory location to the south. By going west across the Great Salt Lake from Ogden, Utah, to Lucin, Utah, the new railroad line shortened the distance by 43 miles and avoided curves and grades. Main line trains no longer passed over Promontory Summit.

In 1942, the old rails over Promontory Summit were salvaged for the war effort; the event was marked by a ceremonial "undriving" of the last iron spike. The original event had been all but forgotten except by local residents, who erected a commemorative marker in 1943. The following year a commemorative postage stamp was issued to mark the 75th anniversary. The years after the war saw a revival of interest in the event; the first re-enactment was staged in 1948.

In 1957, Congress established the Golden Spike National Historic Site to preserve the area around Promontory Summit as closely as possible to its appearance in 1869. O'Connor Engineering Laboratories in Costa Mesa, California, designed and built working replicas of the locomotives present at the original ceremony for the Park Service. These engines are drawn up face-to-face each Saturday during the summer for a re-enactment of the event.[11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18][19]

For the May 10, 1969, centennial of the driving of the last spike, the High Iron Company ran a steam-powered excursion train round trip from New York City to Promontory. The Golden Spike Centennial Limited transported over 100 passengers including, for the last leg into Salt Lake City, actor John Wayne. The Union Pacific Railroad also sent a special display train and the US Army Transportation Corp sent a steam-powered 3-car special from Fort Eustis, Virginia.

On May 10, 2006, on the anniversary of the driving of the spike, Utah announced that its state quarter design would be a depiction of the driving of the spike. The Golden Spike design was selected as the winner from among several others by Utah's governor, Jon Huntsman, Jr., following a period during which Utah residents voted and commented on their favorite of three finalists.[20]

A replica of the Jupiter (CP# 60) at the Golden Spike National Historic Site

A replica of the Jupiter (CP# 60) at the Golden Spike National Historic Site A replica of UP# 119 at Golden Spike N.H.S.

A replica of UP# 119 at Golden Spike N.H.S. The current site of the Golden Spike National Historic Site, with replicas of No. 119 and the Jupiter facing each other to re-enact the driving of the Golden Spike.

The current site of the Golden Spike National Historic Site, with replicas of No. 119 and the Jupiter facing each other to re-enact the driving of the Golden Spike.

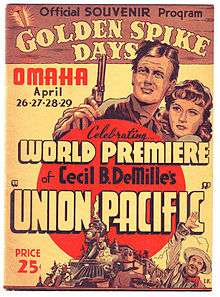

"Golden Spike Days Celebration" (1939)

An elaborate four-day event called the "Golden Spike Days Celebration" was held in Omaha, NE, from April 26 to 29, 1939, to commemorate the 70th anniversary of the joining of the UP and CPRR rails and driving of the Last Spike at Promontory Summit, UT, in 1869. The center piece event of the celebration occurred on April 28 with the World Premiere of the Cecil B. DeMille feature motion picture Union Pacific which took place simultaneously in the city's Omaha, Orpheum, and Paramount theaters. The film features an elaborate reenactment of the original Golden Spike ceremony (filmed in Canoga Park, CA) as the motion picture's closing scene for which DeMille borrowed the actual Golden Spike from Stanford University to be held by Dr. W.H. Harkness (Stanley Andrews) as he delivered his remarks prior to its driving to complete the railroad. (A prop spike was used for the actual hammering sequence.)[21]

Also included as a part of the overall celebration's major attractions was the Golden Spike Historical Exposition, a large assemblage of artifacts (including the Golden Spike itself), tools, equipment, photographs, documents, and other materials from the construction of the Pacific Railroad that were put on display at Omaha's Municipal Auditorium. The four days of events drew over 250,000 people to Omaha during its run, a number roughly equivalent to the city's then population.[22] The celebration was opened by President Franklin D. Roosevelt who inaugurated it by pressing a telegraph key at the White House in Washington, DC.[23][24][25]

On the same day as the premiere of the movie, a still standing gold-colored concrete spike called the "Golden Spike Monument" and measuring some 56 feet (17 m) in height was also unveiled at 21st Street and 9th Avenue in Council Bluffs, IA, adjacent to the UP's main yard, the location of milepost 0.0 of that road's portion of the Pacific Railroad.[26][27]

In popular culture

Artwork

- In 2012, Artist Greg Stimac used the original "golden spike", on display at the Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University, to produce a series of photograms, or cameraless photographs.[28][29]

Films

- The first motion picture depiction of the driving of the golden spike occurred in The Iron Horse 1924, a silent film directed by John Ford and produced by Fox Film.[30] In 2011, this film was deemed "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant" by the United States Library of Congress and selected for preservation in the National Film Registry.[31]

- In the fictional action adventure comedy film Wild Wild West (1999), the joining ceremony is the setting of an assassination attempt on then U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant by the film's antagonist Dr. Arliss Loveless. (In reality Grant did not attend the Golden Spike ceremony.) The extensive Promontory Summit set for the film's Golden Spike ceremony scenes was built at the 20,000-acre Cook's Ranch near Santa Fe, New Mexico.[32]

- The Golden Spike Ceremony is depicted in the movie adaptation of The Lone Ranger (2013) starring Johnny Depp.

Television

- Hell on Wheels presents a multi-season arc on the construction of the transcontinental railroad. In Season 5, Episode 11, a flash forward sequence includes a picture of the railroad ceremony and a main character claiming to possess a ring made of gold crafted from part of the ceremonial golden spike. [33]

- In Lisa's Substitute, (The Simpsons, Season 2, Episode 19, 1991), Leland Stanford's driving of the golden spike is mentioned in a brief, romantic, portrayal of the railroad in the United States. [34]

Toys

In 2015, a Lego model depicting the golden spike ceremony was submitted to the Lego Ideas website.[35][36]

Music

- Railroad Earth, a bluegrass band, frequently performs a song about the event, titled "The Jupiter and the 119".[37][38]

Trains

- The Inyo, a 4-4-0 steam locomotive built for the Virginia & Truckee Railroad (V&T #22) in 1875 by the Baldwin Locomotive Works in Philadelphia, appeared in both the Golden Spike ceremony scene in Union Pacific (1939) and in the 1960s TV series The Wild Wild West. In May, 1969, the Inyo participated in the Golden Spike Centennial at Promontory, Utah, and then served as the replica of the Central Pacific's Jupiter (CPRR #60) at the Golden Spike National Historical Site, until the current replica was built in 1979. Purchased by the Nevada State Railroad Museum in Carson City, Nevada, in 1974, it was eventually brought back to Nevada and fully restored there in 1983, where it still runs today.[39]

See also

References

- ↑ "The Last Spike" by Thomas Hill, 1881 The Central Pacific Photographic History Museum

- ↑ Family Collections at the Cantor Arts Center Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Bowman, J.N. "Driving the Last Spike at Promontory, 1869", California Historical Society Quarterly, Vol. XXXVI, No. 2, June 1957, pp. 96–106, and Vol. XXXVI, No. 3, September 1957, pp. 263–274.

- ↑ "Ceremony at "Wedding of the Rails," May 10, 1869 at Promontory Point, Utah". World Digital Library. 1869-05-10. Retrieved 2013-07-20.

- ↑ "Deseret Morning News". April 24, 2007.

- ↑ Rohwer, Tim (October 18, 2015). "The Daily Nonpareil". Retrieved July 8, 2016.

- ↑ California State Parks

- ↑ San Francisco Newsletter & California Advertiser Vol IX, No. 15. Transcontinental Railroad Postscript Supplement, p. 4. May 15, 1869

- ↑ Mildred Brooke Hoover, Douglas E. Kyle (2002). Historic spots in California. Stanford University Press. p. 378. ISBN 978-0-8047-4482-9.

- ↑ Forrest, Kenton; Albi, Charles (1981). Denver's railroads : the story of Union Station and the railroads of Denver. Golden, Colo.: Colorado Railroad Museum. pp. 1–2. ISBN 9780918654311.

- ↑ Pentrex, 1997.

- ↑ "Colored Steam Locomotives," SteamLocomotive.com (http://www.steamlocomotive.com/colored/) Retrieved 8-17-2011.

- ↑ "Question: Engineering Drawings for the Jupiter and No. 119," CPRR Discussion Group (http://discussion.cprr.net/2005/10/question-engineering-drawings-for.html), Retrieved 8-17-2011.

- ↑ "Golden Spike," National Park Service, Dept. of the Interior, Golden Spike National Historic Site, Brigham City, UT (http://www.nps.gov/gosp/historyculture/upload/jupiter%202.pdf), Retrieved 8-17-2011.

- ↑ "Union Pacific's 119" Golden Spike Pictures (http://users.tns.net/~path/GS119.html), Retrieved 8-17-2011.

- ↑ Gest, Gerald M., Promontory's Locomotives, pp. 12-43, Golden West Books, San Marino, CA, 1980.

- ↑ "Central Pacific Jupiter and Union Pacific 119 at Promontory, UT, 6-8-09" YouTube video, Retrieved 11/24/11.

- ↑ Dowty, Robert R., Rebirth of the Jupiter and the 119: Building the Replica Locomotives at Golden Spike, pp. 5-46, Southwest Parks & Monuments Ass'n., 1994.

- ↑ "Promontory Locomotive Project: Plans for the Jupiter and No. 119," DVD, Western National Parks Ass'n.

- ↑ Roche, Lisa Riley (11 May 2006). "Utahns pick railroad quarter". Deseret News. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ↑ "DeMille Borrows Golden Spike" The United Press (Wire Service), January 19, 1939

- ↑ "Omaha Goes Ballyhoo for Hollywood in Great Style" The United Press (Wire Service), April 27, 1939

- ↑ "Golden Spike Days" The Official Souvenir Program celebrating the World Premiere of Cecil B. DeMille's "Union Pacific" Omaha April 26-27-28-29". Golden Spike Days Celebration, Inc., April, 1939

- ↑ "Golden Spike Days - Omaha, Nebraska - April 26 - 29, 1939" HistoricOmaha.com

- ↑ "Cecil B. DeMille 1939 film "Union Pacific" Golden Spike Days Brass Novelty Railroad Spike" CPRR.org

- ↑ "Golden Spike Monument Council Bluffs Department of Parks, Recreation and Public Safety

- ↑ "Golden Spike Monument, Council Bluffs, IA" rgusrail.com

- ↑ Stanford Arts arts.stanford.edu

- ↑ School of the Art Institute of Chicago photoblobby.wordpress.com

- ↑ "Progressive Silent Film List: The Iron Horse". Silent Era. Retrieved 2008-03-01.

- ↑ 2011 Additions to the National Film Registry Library of Congress, December 28, 2011

- ↑ The Wild Wild West Re-enactor Credits Leavey Foundation for Historic Preservation (ushist.com)

- ↑ http://www.vulture.com/2016/07/hell-on-wheels-recap-season-5-episode-11.html

- ↑ http://www.simpsonsworld.com/video/288011331912

- ↑ Lego Ideas - Golden Spike Ceremony

- ↑ Salt Lake Tribune - How this Utah monument could become a new Lego set

- ↑ http://www.hobocompanion.org/songs/the-jupiter-and-the-119

- ↑ Railroad Earth - Jupiter & the 119 on YouTube

- ↑ V&T No. 22 "INYO" Nevada State Railroad Museum

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Golden Spike National Historic Site. |

- Golden Spike National Historic Monument

- The Golden Spike Centennial Limited of 1969 at ThemeTrains.com.

- Golden Spike Tower and Visitors Center (Nebraska)

- Virtual Museum of the City of San Francisco: Driving the Last Spike

- Fort Ogden web site showing reenactment

- Central Pacific Railroad Photographic History Museum

- Chinese at Promontory, May 10, 1869.

- A New Look at the Golden Spike

- Catalog record for the Golden spike at the Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University