Gong (band)

| Gong | |

|---|---|

|

Gong live in Tel Aviv, 31 October 2009 Steve Hillage, Gilli Smyth, Chris Taylor, Dave Sturt, Daevid Allen (from left to right) | |

| Background information | |

| Origin | Paris, France |

| Genres | Psychedelic rock, space rock, jazz rock[1] |

| Years active | 1967-1968, 1969–1976, 1977, 1990, 1992–2001, 2003–2006, 2007–present |

| Labels | BYG Actuel, Virgin, Charly, Snapper |

| Associated acts | Daevid Allen, Soft Machine, Pierre Moerlen's Gong, Steve Hillage, Here & Now |

| Website |

www |

| Members |

Fabio Golfetti Dave Sturt Ian East Kavus Torabi Cheb Nettles |

| Past members | See article |

Gong is an international psychedelic rock band known for incorporating elements of jazz and space rock into its musical style.[2] The group was formed in Paris in 1967 by Australian musician Daevid Allen and English vocalist Gilli Smyth. Notable band members have included Didier Malherbe, Pip Pyle, Steve Hillage, Mike Howlett, Pierre Moerlen, Bill Laswell and Theo Travis. Others who have played on stage with Gong include Don Cherry,[3] Chris Cutler, Bill Bruford, Brian Davison, Dave Stewart and Tatsuya Yoshida.

Gong released its debut album, Magick Brother, in 1970, which featured a psychedelic pop sound.[4] By the following year, the second album, Camembert Electrique, featured the more psychedelic rock/space rock sound with which they would be most associated.[1] Between 1973 and 1974, Gong released their best known work, the allegorical Radio Gnome Invisible trilogy, describing the adventures of Zero the Hero, the Good Witch Yoni and the Pot Head Pixies from the Planet Gong.

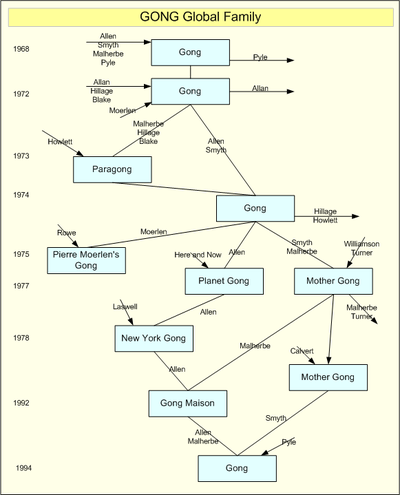

In 1975, Daevid Allen & Gilli Smyth left the band, which continued without them, releasing a series of jazz rock albums under the leadership of drummer Pierre Moerlen. This incarnation of the band became known as Pierre Moerlen's Gong. Meanwhile, Smyth formed Mother Gong while Allen initiated a series of spin-off groups, including Planet Gong, New York Gong and Gongmaison, before returning to lead Gong once again in 1990 until his death in 2015. With Allen's encouragement, the band decided to continue and released the album Rejoice! I'm Dead! on 16 September 2016.[5]

History

Protogong (1967–68)

In September 1967, Australian singer and guitarist Daevid Allen, a member of the English psychedelic rock band Soft Machine, was denied re-entry to the United Kingdom for 3 years following a French tour, because his visa had expired.[6] He settled in Paris, where he and his partner, London-born Sorbonne professor Gilli Smyth, established the first incarnation of Gong (later referred to by Allen as "Protogong"[7]) along with Ziska Baum on vocals and Loren Standlee on flute.[8] However, the nascent band came to an abrupt end during the May 1968 student revolution, when Allen and Smyth were forced to flee the country after a warrant was issued for their arrest. They headed for Deià in Majorca, where they had lived for a time in 1966.

Gong 'proper' begins (1969–71)

In August 1969, film director Jérôme Laperrousaz, a close friend of the pair, invited them back to France to record a soundtrack for a motorcycle racing movie which he was planning. This came to nothing at the time, but they were subsequently approached by Jean Karakos of the newly-formed independent label BYG Actuel to record an album, and so set about forming a new electric Gong band in Paris, recruiting their first rhythm section of Christian Tritsch (bass) and Rachid Houari (drums & percussion) and re-connecting with a saxophonist called Didier Malherbe whom they had met in Deià.[9] However, Tritsch was not ready in time for the sessions and so Allen played the bass guitar himself. The album, entitled Magick Brother, was completed in October.

The re-born Gong played its debut gig at the BYG Actuel Festival in the small Belgian town of Amougies, on 27 October 1969, joined by Danny Laloux on hunting horn & percussion, and Dieter Gewissler & Gerry Fields on violin, and was introduced to the stage by bemused compere Frank Zappa.[10] Magick Brother was released in March 1970, followed in April by a non-album single, "Est-Ce Que Je Suis; Garçon Ou Fille?" b/w "Hip Hip Hypnotise Ya", which again featured Laloux and Gewissler.[11] In October, the band moved into an abandoned 12-room hunting lodge called Pavillon du Hay, near Voisines and Sens, 120 km south-east of Paris. They would be based there until early 1974.[12]

Houari left the band in the spring of 1971 and was replaced by English drummer Pip Pyle, whom Allen had been introduced to by Robert Wyatt during the recording of his debut solo album, Banana Moon. The new line-up recorded a soundtrack for Laperrousaz's movie, now entitled Continental Circus, and played at the second Glastonbury Festival, later documented on the Glastonbury Fayre album.[13] Next, they began work on their second studio album, Camembert Electrique, later referred to by Allen as "the first real band album".[14] It established the progressive, space rock sound which would make their name, leading, in the autumn, to their first UK tour. However, by the end of the year Pyle had left the group, to be replaced by another English drummer, Laurie Allan.[15]

The Radio Gnome Invisible trilogy (1972–74)

1972 saw the start of increasing line-up disruption for Gong. Laurie Allan left in April to be replaced by Mac Poole, then Charles Hayward and then Rob Tait, before returning again late in the year. Gilli Smyth left for a time to look after her and Daevid Allen's baby son and was replaced by Diane Stewart, who was the partner of Tait and the ex-wife of Graham Bond. Christian Tritsch moved to guitar and was replaced on bass by former Magma member Francis Moze, while the band's sound was expanded with the addition of synthesizer player Tim Blake.

In October they were one of the first acts to sign to Richard Branson's fledgling Virgin Records label, and in late December traveled to Virgin's Manor Studio in Oxfordshire, England, to record their third album, Flying Teapot. As they settled in, they were played a rough mix of Mike Oldfield's Tubular Bells, then already in production.[16] Towards the end of their recording sessions they were joined by English guitarist Steve Hillage, whom they had met a few weeks earlier in France playing with Kevin Ayers, and who had replaced Oldfield in Ayers' band. He arrived too late to contribute much to the album,[17] but would soon become a key component in the Gong sound.

Flying Teapot was released on 23 May 1973, the same day as Tubular Bells, and was the first installment of the Radio Gnome Invisible trilogy, which expounded upon the (previously only hinted at) Gong mythology developed by Allen. The second part, Angel's Egg, followed in December, now featuring the 'classic' rhythm section of Mike Howlett on bass and Pierre Moerlen on drums. In early 1974 both Moerlen and Smyth left for a time and were replaced once again by Rob Tait and Diane Stewart, and the band moved from their French base at Pavillon du Hay to an English one, at Middlefield Farm, near Witney, Oxfordshire.[18] Moerlen and Smyth returned to complete the trilogy with You, but by the time of its release, in October 1974, Moerlen had departed once again to work with the French contemporary ensemble Les Percussions de Strasbourg. He was initially replaced by a succession of stand-ins (Chris Cutler, Laurie Allan & Bill Bruford) before former Nice drummer Brian Davison took the job, staying until July 1975.[19]

In June 1974, Camembert Electrique was given a belated UK release by Virgin, priced at 59p, the price of a typical single at the time; a promotional gimmick which they had used before for Faust and would use again for a reggae compilation in 1976. These ultra-budget albums sold in large quantities because of the low price, but this pricing made them ineligible for placement on the album charts. The intention was that purchasers would be encouraged to buy the groups' other albums at full price.

Daevid Allen's departure and Shamal (1975–76)

At a gig in Cheltenham in April 1975, Allen refused to go on stage, claiming that a "wall of force" was preventing him, and left the band.[20] With both Smyth, who wanted to spend more time with her two children, and synth player Tim Blake having already left in previous months, this marked the end of the 'classic' line-up.

Pierre Moerlen was persuaded to return once again in August, and the band continued, adding Mireille Bauer on percussion and Jorge Pinchevsky on violin. They toured the UK in November 1975, as documented on the 2005 release Live in Sherwood Forest '75, and worked on material for their next album, Shamal. However, Hillage became increasingly uncomfortable without Allen and with now being seen as the band's de facto leader. He and his partner Miquette Giraudy, who had taken over from Smyth in late 1974, left before Shamal was released in February 1976, although they had participated in it as guests.[21] Both re-joined Gong briefly for the 1977 reunion concert in Paris, along with Allen, Smyth, Malherbe, Blake, Howlett and Moerlen, as documented on the live album Gong est Mort, Vive Gong.

Pierre Moerlen's Gong and other 70s offshoots (1976–80)

Drummer Pierre Moerlen, who had been persuaded by Virgin to rejoin Gong in 1975 as co-leader, gradually took over sole leadership after Mike Howlett left in 1976. When Malherbe, the only remaining founding member, left in 1977, Moerlen formed a new percussion-based line-up with American bassist Hansford Rowe and percussionists Mireille Bauer and his brother Benoit Moerlen. To avoid confusion, it became known as Gong-Expresso and then, from 1978 onwards, as Pierre Moerlen's Gong. Their last album, Pentanine, was recorded in 2002 and Moerlen died unexpectedly in May 2005, aged 53.

Daevid Allen continued to develop the Gong mythology in his solo albums and with two new bands: Planet Gong (1977), which comprised Allen and Smyth playing with the British festival band Here & Now, and New York Gong (1979), comprising Allen and the American musicians who would later become known as Material. At the same time, Gilli Smyth formed Mother Gong with English guitarist/producer Harry Williamson and Didier Malherbe, and played in Spain and England. Allen delighted in this proliferation of groups and considered his role at this time to be that of an instigator, traveling around the world leaving active Gong-related bands in his wake.

Gongmaison and reunion (1989–92)

After spending most of the Eighties in his native Australia, Allen returned to the UK in 1988 with a new project, The Invisible Opera Company of Tibet, whose revolving cast included violinist Graham Clark and Gong saxophonist Didier Malherbe. This morphed into Gongmaison in 1989, which added Harry Williamson from Mother Gong and had a techno-influenced sound with electronic beats, as well as live percussion from Shyamal Maïtra. In 1990 the Gong name was revived for a one-off U.K. T.V. appearance with a line-up featuring Allen, Smyth and Malherbe, plus early 70s drummer Pip Pyle and three members of Here & Now: Stephen Lewry (lead guitar), Keith Bailey (bass) and Paul Noble (synth). In April 1992, Gongmaison became Gong permanently with the combined line-up of Allen, Malherbe, Bailey and Pyle, plus Graham Clark and Shyamal Maïtra from Gongmaison. Together they recorded the album Shapeshifter (subsequently dubbed Radio Gnome Invisible, Part 4) and toured extensively.[22]

25th anniversary celebration (1994) and worldwide touring (1996–2001)

In 1994, Gong celebrated its 25th birthday with a show in London which featured the return of Gilli Smyth, bassist Mike Howlett and lead guitarist Stephen Lewry of Here & Now. This formed the basis of the band which toured worldwide from 1996 to 2001, with Pierre Moerlen replacing Pip Pyle on drums from 1997 through 1999.[23] The album Zero to Infinity was released in 2000, by which time the line-up had changed again to Allen, Smyth, Malherbe and Howlett, plus new recruits Theo Travis on sax and Chris Taylor on drums. This line-up was unique in the band's history in having two sax/flute players.

Acid Mothers Gong (2003–04)

2003 saw a radical new line-up including Acid Mothers Temple members Kawabata Makoto and Cotton Casino, plus University of Errors guitarist Josh Pollock. Allen and Smyth's son Orlando drummed on the 2004 studio album Acid Motherhood, but for the subsequent live dates the rhythm section was Ruins drummer Tatsuya Yoshida and Acid Mothers Temple bassist Tsuyama Atsushi. A live album recorded by this line-up in 2004 was released as Acid Mothers Gong Live Tokyo and they played a few more more one-off shows in 2006 and 2007.

Gong Family Unconventions (2004–06)

The European version of Gong had retired from regular touring in 2001, but there were subsequent one-off reunions, most notably at the "Gong Family Unconventions" (Uncons), the first of which was held in 2004 in the Glastonbury Assembly Rooms as a one-day event and featured many ex-members and Gong family bands including Here & Now, House of Thandoy, Thom the Poet, Invisible Opera Company, Andy Bole, Bubbledub and Joie Hinton. The 2005 Uncon was a 2-day affair featuring several Gong-related bands such as Here & Now, System 7, House of Thandoy and Kangaroo Moon. The next Uncon was a 3-day event held at the Melkweg in Amsterdam on 3–5 November 2006, with practically all Gong-related bands present: 'Classic' Gong (Allen, Smyth, Malherbe, Blake, Howlett, Travis, Taylor, plus the return of Steve Hillage and Miquette Giraudy), System 7, The Steve Hillage Band, Hadouk, Tim Blake & Jean-Philippe Rykiel, University of Errors, Here & Now, Mother Gong, Zorch, Eat Static, Sacred Geometry Band, Acid Mothers Gong and many others. These events have all been compèred by Thom the Poet (now "Thom Moon 10").[24]

Gong Global Family (2007)

In November 2007, Daevid Allen held a series of concerts in Brazil with a new band which he called Gong Global Family. This consisted of Allen on vocals and guitar, Josh Pollock on guitar, Fabio Golfetti (of Violeta de Outono) on guitar, Gabriel Costa (also from Violeta de Outono) on bass, Marcelo Ringel on flute and tenor saxophone, and Fred Barley on drums. He also performed with his other band, University of Errors (Allen, Pollock, Barley & Michael Clare). These shows took place in São Paulo on 21 and 22 November and São Carlos on 24 November. The 21 November show was filmed and released in the UK on DVD and CD by Voiceprint Records. These musicians, minus Marcelo, also recorded some new songs at Mosh studio, São Paulo.

Continuing to record, tour and evolve (2008–14)

In June 2008, Gong played two concerts in London, at Queen Elizabeth Hall on the South Bank (opening Massive Attack's Meltdown festival) and at The Forum, with a line-up of Allen, Smyth, Hillage, Giraudy, Howlett, Taylor and Travis. This line-up then released a new album, 2032, in 2009 and toured in support, including the Glade stage at Glastonbury Festival. They played at The Big Chill festival in the UK on 9 August 2009 with Allen, Smyth, Hillage, Giraudy, Travis, Taylor and new bassist Dave Sturt, as well as the Beautiful Days festival in Devon and the Lounge On The Farm festival near Canterbury.

Gong played four UK live shows in September 2010 with Allen, Smyth, Hillage, Giraudy, Sturt, Taylor and new wind player Ian East. Support for these shows was provided by Nik Turner's Space Ritual.

Gong toured Europe in the fall of 2012 with the line-up of Allen, Smyth, Sturt & East, plus Orlando Allen (Acid Mothers Gong) on drums, and Fabio Golfetti (Gong Global Family) on guitar.[25] It would be Gilli Smyth's final tour with the band.

They played in Brazil in May 2013 and again in 2014, this time with the addition of Kavus Torabi on guitar.

The 2014 line-up released a new studio album entitled I See You on 10 November, with Gilli Smyth guesting.[26] However, Daevid Allen had been diagnosed with a cancerous cyst in his neck and had to undergo radiation therapy followed by an extensive period of recuperation. The I See You tour went ahead without him, and the line-up of Sturt, East, Golfetti, Torabi and a "mystery drummer" (revealed to be Cheb Nettles) played five dates in France and two in the UK.

The passing of Daevid Allen and Gilli Smyth (2015–16)

On 5 February 2015, Daevid Allen released a statement announcing that the cancer had returned to his neck and had also spread to his lungs, and that he was "not interested in endless surgical operations", leaving him with "approximately six months to live".[27][28] Just over a month after the initial announcement, on 13 March 2015, Daevid's son Orlando announced through Facebook that Allen had died in Byron Bay, Australia, aged 77.[29]

On 11 April 2015, it was revealed that Allen had written an email to the band prior to his death, expressing his wish that the five remaining members continue performing following his passing and suggesting that Kavus Torabi become the new frontman of the band.[30]

Gilli Smyth passed away on 22 August 2016, aged 83. She had been admitted to hospital in Byron Bay with pneumonia a couple of days previously.[31]

Post-Daevid Allen: Rejoice! I'm Dead! (2016–present)

On 5 July 2016, it was announced that the band had recorded a new album, Rejoice! I'm Dead!, featuring Kavus Torabi, Fabio Golfetti, Dave Sturt, Ian East and Cheb Nettles. It features guest appearances from Steve Hillage and Didier Malherbe, and Daevid Allen's vocals appear on two tracks. The album was released on 16 September 2016 through Snapper Music.[5]

Music and lyrics

Style and influences

Gong's music fuses many influences into a distinctive style which has been variously described by critics and journalists as experimental rock,[32] jazz fusion,[33] jazz rock,[34][35] progressive rock,[33][36][37][38][39][40] psychedelic rock[33][40][41] and space rock.[42][43] Gong has also been associated with the Canterbury scene of progressive rock bands.[36]

Rolling Stone described Gong's music as combining "psychedelic English whimsy, German kosmische space jams and Gallic libertine fusion."[44]

Daevid Allen's guitar playing was influenced by Syd Barrett.[45]

Mythology

The Gong mythology is a humorous collection of recurring characters and allegorical themes which permeate the albums of Gong and Daevid Allen, and to a lesser extent the early works of Steve Hillage. The characters were often based on, or used as pseudonyms for, band members, while the story itself was based on a vision which Allen had during the full moon of Easter 1966, in Deià, Majorca, in which he claimed he could see his future laid out before him.[46] This mythology was hinted at through Gong's earlier albums but was not the central theme until the Radio Gnome Invisible trilogy of 1973/74. It contains many similarities to concepts from Buddhist philosophy, e.g. optimism, the search for self, the denial of absolute reality and the search for the path to enlightenment. There are frequent references to the production and consumption of "tea", perhaps suggesting mushroom tea, although the word has also long been used to describe cannabis, especially in the 1940s and 1950s.

Flying Teapot: Radio Gnome Invisible, Part 1 (1973)

The story begins on the album Flying Teapot (1973), when a pig-farming Egyptologist called Mista T. Being is sold a "magick ear ring" by an "antique teapot street vendor & tea label collector" called Fred the Fish. The ear ring is capable of receiving messages from the Planet Gong via a pirate radio station called Radio Gnome Invisible. Being and Fish head off to the Hymnalayas of Tibet (sic) where they meet the "great beer yogi" Banana Ananda in a cave. Ananda tends to chant "Banana Nirvana Mañana" a lot and gets drunk on Foster's Australian Lager. (This latter development mirrors the real-life experience of band members Daevid Allen and Gilli Smyth who met their saxophonist, Didier Malherbe, in a cave in Majorca.)

Meanwhile, the mythology's central character, Zero the Hero, is going about his everyday life when he suddenly has a vision in Charing Cross Road, London. He is compelled to seek heroes and starts worshiping the Cock Pot Pixie, one of a number of Pot Head Pixies from the Planet Gong. These pixies are green, have propellers on their heads, and fly around in teapots (inspired by [Bertrand] Russell's teapot).[47]

Zero is soon distracted by a cat to whom he offers his fish and chips. The cat is actually The Good Witch Yoni, and she gives Zero a potion in return.

Angel's Egg: Radio Gnome Invisible, Part 2 (1973)

The second part, Angel's Egg (1973), begins with Zero falling asleep under the influence of the potion and finding himself floating through space. After accidentally scaring a space pilot called Captain Capricorn, Zero locates the Planet Gong, and spends some time with a prostitute who introduces him to the moon goddess Selene.

Zero's drug-induced trip to the Planet Gong continues, and the Pot Head Pixies explain to him how their flying teapots fly: a system known as Glidding. He is then taken to the One Invisible Temple of Gong.

Inside the temple, Zero is shown the Angel's Egg, the physical embodiment of the 32 Octave Doctors (descendants of the Great God Cell). The Angel's Egg is the magic-eye mandala that features on much of the band's sleeve-art. It is also a sort of recycling plant for Pot Head Pixies.

A grand plan is revealed to Zero: there will be a Great Melting Feast of Freeks which Zero must organise on Earth. When everyone is enjoying the Feast, a huge global concert, the Switch Doctor will turn everybody's third eye on, ushering in a New Age on Earth. The Switch Doctor is the Earth's resident Octave Doctor, who lives near Banana Ananda's cave, in a "potheadquarters" called the Compagnie d'Opera Invisible de Thibet (C.O.I.T.) and transmits all the details to the Gong Band via the Bananamoon Observatory.

You: Radio Gnome Invisible, Part 3 (1974)

In the third instalment, You (1974), Zero must first return from his trip. He asks Hiram the Master Builder how to structure his vision and build his own Invisible Temple. Having done this, Zero establishes that he must organise the Great Melting Feast of Freeks on the Isle of Everywhere: Bali.

The event is going well, and the Switch Doctor switches on everyone's third eyes except for Zero's, for he is out the back, indulging in Earthly pleasures ("fruitcake").

Zero has missed out on the whole third eye revelation experience and is forced to continue his existence spinning around on the wheel of births and deaths and slowly converging on the Angel's Egg in a way which, to a certain extent, resembles Buddhist reincarnation.

Continuations (1992–2009)

The album Shapeshifter (1992) is the fourth installment in the saga, in which Zero meets an urban shaman who agrees to take him to the next level of awareness on the proviso that Zero spends nine months on an aeroplane traveling where he wants, but not using money or eating anything other than airline food. Zero eventually dies in Australia under mysterious circumstances.

The next installment is the album Zero to Infinity (2000), which sees Zero's spirit enjoying a body-free and virtual existence. During the course of this he becomes an android spheroid Zeroid. With the help of a strange animal called a gongalope, he learns that all the wisdom of the world exists within him and practices Lafta yoga and tea making. At the end he becomes one with an Invisible Temple and has a lot of fun.

The final installment of the story, 2032 (2009), is set in that year, one which Daevid Allen had seen as significant for the enlightenment of humanity. The Planet Gong now serves as more of a digital portal for a humanity still grappling with contemporary issues of life.

Influence on other artists

Gong's influence has been seen in artists such as Ozric Tentacles[48][49] and Insane Clown Posse, whose member Violent J listened to Gong's music for inspiration during the recording of ICP's 2009 album Bang! Pow! Boom![50] Gong's music has also found fandom in the ambient music scene.[51]

American hard rock band Raging Slab has covered Gong's "The Pot Head Pixies" for NORML's Hempilation release. Japanese psych-rock band Acid Mothers Temple frequently covers Gong's "Master Builder", titled as "Om Riff", and have released 2 full albums dedicated to album-length renditions of the song; 2005's "IAO Chant From The Cosmic Inferno" and 2012's "IAO Chant From The Melting Paraiso Underground Freak Out".

Hip hop artists have sampled Gong's music.[52] Madlib samples Gong's music frequently, including "Eat That Phone Book Coda" on his song ""Maingirl", "You Never Blow Yr Trip Forever" on "Bullyshit", and "Shamal" on "Mr. Two-Faced". Insane Clown Posse has also frequently sampled Gong, including "The Pot Head Pixies" on "Ringmaster's Word" and "Toy Box", as well as "Selene" on "The Dead One" and "Bambooji" on "For The Maggots".

Actor Sherman Hemsley, best known for his role on The Jeffersons, was an avowed Gong fanatic, going so far as to have a Flying Teapot room in his house. The room, which had darkened windows, played Flying Teapot continuously via tape loops.[53]

Personnel

- Current members

- Fabio Golfetti – lead guitar (2007, 2012–present)

- Dave Sturt – bass (2009–present)

- Ian East – saxophone, flute (2010–present)

- Kavus Torabi – guitar, vocals (2014–present)

- Cheb Nettles – drums (2014–present)

Discography

Gong

(* Usually regarded as a transitional album between Daevid Allen's incarnation of the band and the Pierre Moerlen-led fusion line-up of the late 1970s.) Planet Gong

New York Gong

Gongmaison

Pierre Moerlen's Gong

|

Mother Gong

Live albums

|

Compilation albums

|

Other appearances

|

Filmography

- 2015: Romantic Warriors III: Canterbury Tales (DVD)

References

- 1 2 David Ross Smith (20 November 2007). "Camembert Électrique - Gong | Songs, Reviews, Credits". AllMusic. Retrieved 2 January 2016.

- ↑ Muggs, Joe (2016-08-25). "The silliness ran deep in Gong, but they could groove like mothers, too". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2016-08-26.

- ↑ Lucky, Jerry. Progressive Rock. Burlington, Ontario: Collector's Guide Publishing, Inc., 2000. p.61

- ↑ "Allmusic ((( Magick Brother > Overview )))". Allmusic. Retrieved 29 October 2009.

- 1 2 "Madfish". www.burningshed.com. Retrieved 2016-08-09.

- ↑ Allen, Daevid. Gong Dreaming 1. SAF Publishing, 2007, p.64.

- ↑ Allen, Daevid. Gong Dreaming 1. SAF Publishing, 2007, p.76.

- ↑ "planet gong bazaar". planetgong.co.uk. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- ↑ Allen, Daevid. Gong Dreaming 2. SAF Publishing, 2009, p.13.

- ↑ Allen, Daevid. Gong Dreaming 2. SAF Publishing, 2009, p.31.

- ↑ Allen, Daevid. Gong Dreaming 2. SAF Publishing, 2009, p.34.

- ↑ Allen, Daevid. Gong Dreaming 2. SAF Publishing, 2009, pgs.52, 67, 291.

- ↑ Allen, Daevid. Gong Dreaming 2. SAF Publishing, 2009, p.110-115.

- ↑ Allen, Daevid. Gong Dreaming 2. SAF Publishing, 2009, p.116.

- ↑ Allen, Daevid. Gong Dreaming 2. SAF Publishing, 2009, p.124-141.

- ↑ Allen, Daevid. Gong Dreaming 2. SAF Publishing, 2009, p.184.

- ↑ Allen, Daevid. Gong Dreaming 2. SAF Publishing, 2009, p.188.

- ↑ Allen, Daevid. Gong Dreaming 2. SAF Publishing, 2009, p.291.

- ↑ See in the gigs section of Planet Gong's website

- ↑ Allen, Daevid. Gong Dreaming 2. SAF Publishing, 2009, p.413.

- ↑ "GONG-Chronology". calyx.perso.neuf.fr/gong. 2014. Retrieved 22 November 2014.

- ↑ "Shapeshifter Gong - Daevid Allen (chant, guitare), Didier Malherbe (saxophones, flûtes, chant), Keith Bailey (basse), Pip Pyle (batterie), Shyamal Maïtra (percussions, tablas), Graham Clark (guitare, violon). Concert enregistré le 1er mai 1992. - À l'écoute des Archives départementales de Saône-et-Loire". Audio.archives71.fr. Retrieved 2 January 2016.

- ↑ "Pierre Moerlen – 1952–2005". planetgong.co.uk. 2014. Retrieved 22 November 2014.

- ↑ "Thom the Poet (now Thom Moon 10)". www.worldpoetry.org. 5 September – 15 October 2011. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- ↑ "Current News". Planet Gong. Retrieved 25 June 2013.

- ↑ "I See You (CD)". Gong Official website. November 2014. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- ↑ "Gong founder Daevid Allen has six months to live". the Guardian. Retrieved 5 February 2015.

- ↑ "planet gong news : : Current News". planetgong.co.uk. Retrieved 5 February 2015.

- ↑ "Gong founder Daevid Allen has died, aged 77". The Guardian. Theguardian.com. 13 March 2015. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- ↑ "Daevid Allen's Farewell Message To Gong". uDiscover. Retrieved 2 January 2016.

- ↑ "Gilli Smyth 1933-2016". Planet Gong. Retrieved 23 August 2016.

- ↑ "Legendary rocker Daevid Allen dies". Msn.com. Retrieved 2 January 2016.

- 1 2 3 "R.I.P. Daevid Allen, founder of Gong and Soft Machine, has died". Consequence of Sound. Retrieved 2 January 2016.

- ↑ "Rock Obituaries – Knocking On Heaven's Door". Books.google.com. Retrieved 2 January 2016.

- ↑ "The New Rolling Stone Encyclopedia of Rock & Roll". Books.google.com. Retrieved 2 January 2016.

- 1 2 "A guide to the best (and a bit of the worst) of prog rock". Avclub.com. Retrieved 2 January 2016.

- ↑ "Gong, Soft Machine Founder Daevid Allen Dead at 77". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 2 January 2016.

- ↑ David Ross Smith. "Camembert Électrique". AllMusic. Retrieved 2 January 2016.

- ↑ "Daevid Allen, Guitarist and Singer in Progressive Rock, Dies at 77". The New York Times. 18 March 2015. Retrieved 2 January 2016.

- 1 2 "Daevid Allen, Founder of Gong and Soft Machine, Dead at 77". Pitchfork. Retrieved 2 January 2016.

- ↑ "Daevid Allen, Frontman of Psychedelic Rock Groups Gong and Soft Machine, has Six Months to Live, Issues Emotional Statement". Classicalite. Retrieved 2 January 2016.

- ↑ Chris Nickson. "Shapeshifter". AllMusic. Retrieved 2 January 2016.

- ↑ Graham St John. "The Local Scenes and Global Culture of Psytrance". Books.google.com. p. 129. Retrieved 2 January 2016.

- ↑ "Gong, 'You' (1974)". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 2 January 2016.

- ↑ DeRogatis, Jim. Turn On Your Mind: Four Decades of Great Psychedelic Rock. Hal Leonard Publishing, 2003

- ↑ Allen, Daevid. Gong Dreaming 1. SAF Publishing, 2007, p.7.

- ↑ Allen, Daevid. Gong Dreaming 2. SAF Publishing, 2009, p.5.

- ↑ "PEPPERMINT IGUANA ozric tentacles interview". Peppermintiguana.co.uk. 21 June 1984. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- ↑ "Get Ready to ROCK! Interviews with Ed Wynne of progressive ambient rock band Ozric Tentacles". Getreadytorock.com. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- ↑ Graham, Adam (11 May 2009). "Insane Clown Posse takes on busiest year yet". The Detroit News.

- ↑ Chris Nickson. "Shapeshifter". AllMusic. Retrieved 2 January 2016.

- ↑ "Gong". WhoSampled. Retrieved 2 January 2016.

- ↑ Myers, Mitch (5 March 2009). "GEORGE JEFFERSON: WORLD'S BIGGEST GONG FAN?". Magnet Magazine. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

Further reading

- Allen, Daevid. Gong Dreaming 1. SAF Publishing, 2007 ISBN 978-0-946719-82-2

- Allen, Daevid. Gong Dreaming 2. SAF Publishing, 2009 ISBN 978-0-946719-56-3

- Brown, Brian. "Gong: Angel's Egg", (Crawdaddy!) 26 March 2008

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gong (band). |

- Official web site for Gong, GAS & Gliss

- Gong at Calyx, The Canterbury Music Website, by Aymeric Leroy - includes detailed chronology

- "Not Just Another Gong Website" – comprehensive tapeography

- The Archive – Archival photos of Gong, Mother Gong, Steve Hillage, Nik Turner, Here & Now, Hawkwind and many Free Festivals from the 1960s–1980s

- Acid Motherhood voted weirdest album cover of all time