Gordon (slave)

| Gordon | |

|---|---|

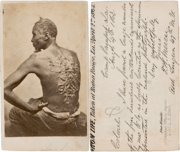

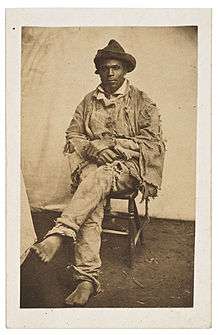

Gordon; an escaped, African-American man, in 1863, just after he reached a Union Army camp, in Baton Rouge, Louisiana | |

| Other names | Whipped Peter, Peter – Gordon is possibly a surname[1] |

| Known for | Pivotal figure in exposing the brutality of slavery |

|

Military career | |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/branch |

|

| Rank | Sergeant |

| Unit | Corps d'Afrique |

| Battles/wars | |

Gordon, or "Whipped Peter", was an enslaved African American who escaped from a Louisiana plantation in March 1863, gaining freedom when he reached the Union camp near Baton Rouge. He became known as the subject of photographs documenting the extensive scarring of his back from whippings received in slavery. Abolitionists distributed these carte de visite photographs of Gordon throughout the United States and internationally to show the abuses of slavery.[2]

In July 1863 these images appeared in an article about Gordon published in Harper's Weekly, the most widely read journal during the Civil War.[3] The pictures of Gordon's scourged back provided Northerners with visual evidence of brutal treatment of slaves and inspired many free blacks to enlist in the Union Army.[4] Gordon joined the United States Colored Troops soon after their founding, and served as a soldier in the war.[5]

Escape

Gordon escaped in March 1863 from the 3,000-acre (12 km2) plantation of John and Bridget Lyons, who owned him and nearly forty other slaves at the time of the 1860 census.[6][7] The Lyons plantation was located along the west bank of the Atchafalaya River in St. Landry Parish, between present-day Melville and Krotz Springs, Louisiana.[8]

In order to mask his scent from the bloodhounds that were chasing him, Gordon took onions from his plantation, which he carried in his pockets. After crossing each creek or swamp, he rubbed his body with these onions in order to throw the dogs off his scent. He fled over 40 miles (64 km)[9] over the course of ten days before reaching Union soldiers of the XIX Corps who were stationed in Baton Rouge.[10]

Arrival at Union camp

Upon arrival at the Union camp, Gordon underwent a medical examination on April 2, 1863, which revealed severe keloid scars from several whippings. Itinerant photographers William D. McPherson and his partner Mr. Oliver, who were in camp at the time, produced carte de visite photos of Gordon showing his back.[11]

During the examination, Gordon is quoted as saying,

"Ten days from to-day I left the plantation. Overseer Artayou Carrier whipped me. I was two months in bed sore from the whipping. My master come after I was whipped; he discharged the overseer."[12] My master was not present. I don't remember the whipping. I was two months in bed sore from the whipping and my sense began to come – I was sort of crazy. I tried to shoot everybody. They said so, I did not know. I did not know that I had attempted to shoot everyone; they told me so. I burned up all my clothes; but I don't remember that. I never was this way (crazy) before. I don't know what make me come that way (crazy). My master come after I was whipped; saw me in bed; he discharged the overseer. They told me I attempted to shoot my wife the first one; I did not shoot any one; I did not harm any one. My master's Capt. JOHN LYON,[13] cotton planter, on Atchafalya, near Washington, Louisiana. Whipped two months before Christmas."[14]

Service in Union Army

Gordon joined the Union Army as a guide three months after the Emancipation Proclamation allowed for the enrollment of freed slaves into the military forces. On one expedition, he was taken prisoner by the Confederates; they tied him up, beat him, and left him for dead. He survived and once more escaped to Union lines.[15]

Gordon soon afterwards enlisted in a U.S. Colored Troops Civil War unit. He was said to have fought bravely as a sergeant in the Corps d'Afrique during the Siege of Port Hudson in May 1863.[16] It was the first time that African-American soldiers played a leading role in an assault.[17]

Legacy

The Atlantic's editor-in-chief James Bennet in 2011 noted, "Part of the incredible power of this image I think is the dignity of that man. He's posing. His expression is almost indifferent. I just find that remarkable. He's basically saying, 'This is a fact.'"[18]

I enclose a picture taken by an artist here, from life, of a Negro's back, exhibiting the scars from an old whipping. Few sensation writers ever depicted worse punishments than this man must have received, though nothing in his appearance indicates any unusual viciousness — but on the contrary, he seems INTELLIGENT and WELL-BEHAVED. [Towle's emphasis]

—Dr. Samuel Knapp Towle, Surgeon, 30th Regiment of Massachusetts Volunteers, in a letter dated 16 April 1863 to William Johnson Dale, Surgeon-general of the State of Massachusetts. Dr. Towle was in charge of the 900-bed United States General Hospital, Baton Rouge in 1863.

There has lately come to us, from Baton Rouge, the photograph of a former slave—now, thanks to the Union army, a freeman. It represents him in a sitting posture, his stalwart body bared to the waist, his fine head and intelligent face in profile, his left arm bent, resting upon his hip, and his naked back exposed to full view. Upon that back, horrible to contemplate! is a testimony against slavery more eloquent than any words. Scarred, gouged, gathered in great ridges, knotted, furrowed, the poor tortured flesh stands out a hideous record of the slave-driver's lash. Months have elapsed since the martyrdom was undergone, and the wounds have healed, but as long as the flesh lasts will this fearful impress remain. It is a touching picture, an appeal so mute and powerful that none but hardened natures can look upon it unmoved. However much men may depict false images, the sun will not lie. From such evidence as this there is no escape, and to see is to believe. Many, therefore, desired a copy of the photograph, and from the original numerous copies have been taken.

The surgeon of the First Louisiana regiment, (colored,) writing to his brother in the city, encloses this photograph, with these words: –

"I send you the picture of a slave as he appears after a whipping. I have seen, during the period I have been inspecting men for my own and other regiments, hundreds of such sights—so they are not new to me; but it may be new to you. If you know of any one who talks about the humane manner in which the slaves are treated, please show them this picture. It is a lecture in itself."

"Picture of a Slave". The Liberator. Boston, Massachusetts. 12 June 1863. p. 2.

We received from Baton Rouge the photographic likeness of a slave's naked back, lacerated by the whip [...] We look on the picture with amazement that cannot find words for utterance. Amazement at the cruelty which could perpetrate such an outrage as this; at the brutal folly, the stupid ignorance, that could permit such a piece of infatuation; at the absence not only of humane feeling, but of economical prudence of common sense, of ordinary intelligence, displayed in such frantic thoughtlessness. Among what sort of people are such things possible? [...] This card-photograph should be multiplied by the hundred thousand, and scattered over the states. It tells the story in a way that even Mrs. Stowe cannot approach; because it tells the story to the eye. If seeing is believing — and it is in the immense majority of cases — seeing this card would be equivalent to believing things of the slave states which Northern men and women would move heaven and earth to abolish!

Theodore Tilton, ed. (28 May 1863). "The Scourged Back". The Independent (New York). XV (756): 4.

Reprint: "The Scourged Back". The Liberator. Boston, Massachusetts. June 19, 1863. p. 1.

In popular culture

- In the 2012 film Lincoln, Abraham Lincoln's son Tad viewed a glass plate of Gordon's medical examination photo by candlelight.[19]

Gallery

|

References

Notes

- ↑ Abruzzo, Margaret (March 29, 2011). Polemical Pain: Slavery, Cruelty, and the Rise of Humanitarianism. JHU Press. p. 309.

- ↑ "The Scourged Slave's Back," The Liberator (Boston, Massachusetts). September 4, 1863. p. 3

- ↑ Heidler 2002

- ↑ Goodyear III, Frank H. "Photography changes the way we record and respond to social issues". Smithsonian Institution

- ↑ Rymer, Eric. "Ten days from today I left the plantation". Historylink101

- ↑ Abruzzo, Margaret (March 29, 2011). Polemical Pain: Slavery, Cruelty, and the Rise of Humanitarianism. JHU Press, p. 309.

- ↑ Population schedules of the eighth census of the United States, 1860, Louisiana

- ↑ Lyons Shaw, Adonica. "Captain John Lyons of St Landry Parish"

- ↑ "Civil War CDV of African American Contraband, Baton Rouge, La.". Cowan's Auctions.

- ↑ "A Typical Negro," Harper's Weekly: 429. July 4, 1863.

- ↑ Shumard, Ann. "Bound for Freedom's Light". Civil War Trust

- ↑ "Scars of slavery". The National Archives

- ↑ Lyons Shaw, Adonica. "Captain John Lyons of St Landry Parish"

- ↑ Rymer, Eric. "Ten days from today I left the plantation". Historylink101

- ↑ "A Typical Negro," Harper's Weekly: 429. July 4, 1863.

- ↑ "A Picture for the Times". The Liberator (Boston). July 3, 1863. p. 3

- ↑ Shumard, Ann. "Bound for Freedom's Light". Civil War Trust

- ↑ Norris, Michele (December 5, 2011). "'The Atlantic' Remembers Its Civil War Stories," NPR

- ↑ "Lincoln Script". IMSDb. Retrieved January 19, 2015.

Tad, in fancy military uniform, sits on the bed, Gardener's box of glass negatives open beside him. He holds up a plate to a lamp:

Bibliography

- "A Picture for the Times". The Liberator. Boston. July 3, 1863. p. 3. Retrieved October 16, 2014 – via Newspapers.com.

- "A Typical Negro". Harper's Weekly: 429. July 4, 1863. Retrieved October 22, 2014.

- Abruzzo, Margaret (Mar 29, 2011). Polemical Pain: Slavery, Cruelty, and the Rise of Humanitarianism. JHU Press. p. 309. ISBN 9781421401270. Retrieved July 30, 2014.

- "Civil War CDV of African American Contraband, Baton Rouge, La.". Cowan's Auctions. Archived from the original on October 22, 2014. Retrieved October 22, 2014.

Civil War CDV of African American Contraband, Baton Rouge, La., 2008, Historic Americana Auction, Dec 4 & 5 with imprint of McPherson & Oliver, Baton Rouge, and verso inked inscription Contraband that marched 40 miles to get to our lines. An exceptional image.

- "Copy photograph of Gordon, a runaway slave.". Yale University Library Catalog. Retrieved September 24, 2014.

- Goodyear III, Frank H. "Photography changes the way we record and respond to social issues". Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on May 1, 2013. Retrieved August 26, 2013.

- Heidler, David Stephen; Heidler, Jeanne T.; Coles, David J. (2002). Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 931. ISBN 039304758X.

- Lyons Shaw, Adonica (n.d.). "Captain John Lyons of St. Landry Parish". Lyons Family website.

- Norris, Michele (December 5, 2011). "'The Atlantic' Remembers Its Civil War Stories". NPR. Retrieved August 24, 2013.

- Population schedules of the eighth census of the United States, 1860, Louisiana. Reel 431 – St. Landry Parish. 1965 [1860]. p. 111. OCLC 22655687. Retrieved January 4, 2015.

- Rymer, Eric. "Ten days from today I left the plantation". Historylink101. Archived from the original on July 28, 2014. Retrieved October 22, 2014.

- "Scars of slavery". The National Archives. Retrieved August 26, 2013.

- "The Scourged Slave's Back". The Liberator. Boston, Massachusetts. September 4, 1863. p. 3. Retrieved August 25, 2014 – via Newspapers.com.

- Shumard, Ann. "Bound for Freedom's Light". Civil War Trust. Retrieved August 24, 2013.

- Silkenat, David (August 8, 2014). ""A Typical Negro": Gordon, Peter, Vincent Coyler, and the Story Behind Slavery's Most Famous Photograph". American Nineteenth Century History. 15: 169–186. doi:10.1080/14664658.2014.939807. Retrieved June 23, 2015.

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gordon (slave). |

- Edwards, Ron. "The Whipping Scars On The Back of The Fugitive Slave Named Gordon". US Slave Blog. Retrieved August 24, 2013.

- Goodyear III, Frank. "The Scourged Back: How Runaway Slave and Soldier Private Gordon Changed History". America's Black Holocaust Museum. Archived from the original on January 5, 2015. Retrieved January 5, 2015.

- Paulson Gage, Joan (September 30, 2009). "A Slave Named Gordon". The New York Times. Retrieved August 24, 2013.

- Paulson Gage, Joan (August 5, 2013). "Icons of Cruelty". The New York Times. Retrieved August 24, 2013.

- Bostonian (December 3, 1863). "The Realities of Slavery". New-York Daily Tribune. p. 4. Retrieved June 27, 2015.