Gothic War (376–382)

- See also Gothic War (535–554) for the war in Italy.

| Gothic War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Relief panel on the Ludovisi Battle sarcophagus depicting a battle between Goths and Romans, circa 260. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Eastern Roman Empire Western Roman Empire |

Therving Goths Greuthungi Goths Alanic raiders Hunnish raiders | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Valens † Gratian Theodosius I |

Fritigern Alatheus Saphrax | ||||||

The Gothic War is the name given to a Gothic uprising in the Eastern Roman Empire in the Balkans between about 376 and 382. The war, and in particular the Battle of Adrianople, is commonly seen as a major turning point in the history of the Roman Empire, the first in a series of events over the next century that would see the collapse of the Western Roman Empire, although its ultimate importance to the Empire's eventual fall is still debated.[1][2]

Background

In the summer of 376, a massive number of Goths arrived on the Danube River, the border of the Roman Empire, requesting asylum from the Huns.[3] They came in two distinct groups: the Thervings led by Fritigern and Alavivus, and the Greuthungi led by Alatheus and Saphrax.[4] Eunapius states their number as 200,000 including civilians, but Peter Heather estimates that the Thervings may have had only 10,000 warriors and 50,000 people in total, with the Greuthungi about the same size.[5] The Cambridge Ancient History places modern estimates at around 90,000 people total.[6]

The Goths sent ambassadors to the Eastern Roman Emperor Valens requesting permission to settle their people inside the Empire.[7] It took them some time to reach him, however, for the Emperor was in Antioch preparing for a campaign against the Sasanian Empire over control of Armenia and Iberia. The bulk of his forces were thus stationed in the East, far away from the Danube.[8] Ancient sources are unanimous that Valens was pleased at the appearance of the Goths, as it offered the opportunity of new soldiers at low cost.[9] But since Valens was heavily committed to action on the Eastern frontier, the appearance of a large number of barbarians meant his skeletal force in the Balkans were outnumbered.[10] Valens must have appreciated the danger when he ultimately gave the Thervings permission to enter the Roman Empire, and the terms he gave them were highly favorable. This was not the first time barbarian tribes had been settled within the Roman Empire. The usual course was that some would be recruited into the army and the rest would be broken up into small groups and resettled across the Empire at the Emperor's discretion. This would keep them from posing a unified threat and assimilate into the greater Roman population. The agreement differed with the Thervings by allowing them to choose the place of their settlement, Thrace, and allowed them to remain as one large group. During the negotiations, the Thervings also expressed a willingness to convert to Christianity. As for the Greuthungi, Roman army and naval forces blocked the river and denied them entry.[11]

The Thervings were probably allowed to cross at or near the fortress of Durostorum.[12] They were ferried by the Romans in boats, rafts, and in hollowed tree-trunks, and "diligent care was taken that no future destroyer of the Roman state should be left behind, even if he were smitten by a fatal disease," according to Ammianus Marcellinus. Even so, the river swelled with rain and many drowned.[13] The Goths were to have their weapons confiscated, but the Romans in charge accepted bribes to allow the Goths to retain their weapons, or perhaps due to there being so many Goths and so few Roman soldiers, not all of them could be adequately checked.[14][15][n 1] The Romans placed the Thervings along southern bank of the Danube in Lower Moesia as they waited for the land allocations to begin.[17] In the interim, the Roman state was to provide them food.[18]

Breakout

So many people in so small an area caused a food shortage, and eventually the Thervings began to starve.[19] Roman logistics could not cope with the vast numbers, and the officials on the ground, under the command of Lupicinus, simply sold off much of the food before it reached the hands of the Goths. Desperate, Gothic families sold many of their children into slavery to Romans for dog meat at the price of one child per one dog.[20][21]

This treatment caused the Therving Goths to grow rebellious, and Lupicinus decided to move them south to Marcianople, his regional headquarters.[22] To guard the march south, Lupicinus was forced to pull out the Roman troops guarding the Danube, which allowed the Greuthungi to cross promptly into Roman territory. The Thervings then deliberately slowed their own march to allow the Greuthungi to catch up.[23] As the Thervings neared Marcianople, Lupicinus invited Fritigern, Alavivus, and a small group of their attendants to dine with him inside the city. The bulk of the Goths were encamped some distance outside, with Roman troops between them and the city. Due to the persistent refusal of the Roman soldiers to allow the Goths to buy supplies in the town's market, fighting broke out and several Roman soldiers were killed and robbed. Lupicinus, having received the news as he sat at the banquet with the Gothic leaders, responded by ordering the executions of Fritgern's and Alavaivus' attendants and holding the leaders hostage. This was done in secret, but news of the killings came to the Goths outside, and they prepared to assault Marcianopole's walls. Fritigern advised Lupicinus that the best way to calm the situation was to allow Fritigern to rejoin his people and show them that he was still alive. Lupicinus, indecisive as to what to do, agreed and set him free. Alavivus is not mentioned again in the sources, and his fate is unknown.[24][25]

Having survived the chaos of the night and the earlier humiliations, Fritigern and the Thervings decided it was time to break the treaty and rebel against the Romans. The Greuthungi immediately joined them. Fritigern led the Goths away from Marcianopole towards Scythia. Lupicinus and his army pursued them fourteen kilometers from the city and fought a battle, but were annihilated. All the junior officers were killed, the military standards were lost, and the bodies of dead Romans provided the Goths with new weapons and armor. Lupicinus survived and escaped back to Marcianopole. The Thervings then raided and pillaged throughout the region.[26][27]

At Adrianople a small Gothic force, employed by the Romans, were garrisoned under the command of Sueridus and Colias. The two Goths had received news of the events, but had preferred to remain in place "considering their own welfare the most important thing of all."[28] The Emperor, afraid of having a Roman garrison under Gothic control so close to a Gothic rebellion, ordered Sueridus and Colias to march east to Hellespontus. The two commanders asked for food and money for the journey, as well as a postponement of two days to prepare. The local Roman magistrate, angry at this garrison for having earlier pillaged his suburban villa, armed people from the city and stirred them against the garrison. The mob demanded that the Goths follow orders and leave immediately. The men under Sueridus and Colias initially stood still, but when they were pelted with curses and missiles from the mob, they attacked and killed many. The garrison left the city and joined Fritigern, and the Goths besieged Adrianople. But lacking the equipment and the experience to conduct a siege, and losing many men to missiles, they abandoned the city. Fritigern declared he now "kept peace with walls". The Goths once again dispersed to loot the rich and undefended countryside. Using prisoners and Roman traitors, the Goths were led to hidden hoards, rich villages, and such places.[29]

| “ | For without distinction of age or sex all places were ablaze with slaughter and great fires, sucklings were torn from the very breasts of their mothers and slain, matrons and widows whose husbands had been killed before their eyes were carried off, boys of tender or adult age were dragged away over the dead bodies of their parents. Finally many aged men, crying that they had lived long enough after losing their possessions and their beautiful women, were led into exile with their arms pinioned behind their backs, and weeping over the glowing ashes of their ancestral homes.[30] | ” |

377: Containing the Goths

Many Goths inside Roman territory joined Fritigern, as did assorted slaves, miners, and prisoners.[31] Roman garrisons in fortified towns held out, but those outside of them were easy prey. The Goths created a vast wagon train to hold all the loot and supplies pillaged from the Roman countryside, and they had much rage against the Roman population for what they had endured. Those who had started as starving refugees had transformed into a powerful army.[32][33]

Valens, now recognizing the seriousness of the situation from his base in far away Antioch, sent general Victor to negotiate an immediate peace with the Sassanids. He also began to transfer the Eastern Roman army to Thrace. While the main army mobilized, he sent ahead an advance force under Traian and Profuturus. Valens also reached out to the Western Roman Emperor Gratian, his co-emperor and nephew, for aid. Gratian responded by sending the comes domesticorum Richomeres and the comes rei militaris Frigeridus, to guard the western passes through the Haemus mountains to contain the Goths from spreading westward and for eventual linkup with the Eastern army. These huge movements of troops, and the cooperation of the West, spoke to the grave threat the Goths posed.[34][35]

Traian and Profuturus arrived leading troops of Armenians. Frigeridus, leading the Pannonian and the transalpine auxiliaries, fell ill from gout. Richomeres, having led a force cut from Gratian's palatine army, by the mutual consent of the other leaders took command of the combined forces, probably at Marcianople.[36][37][38] The Goths withdrew north of the Haemus mountains, and the Romans moved to engage.[39] At a place called Ad Salices[n 2] ("The Willows"), they fought the Battle of the Willows. The Romans were outnumbered, and during the battle their left wing began to collapse. Only with hasty reinforcements and Roman discipline was the situation retrieved. The battle lasted until dusk when the opposing armies broke off, the Goths withdrawing into their wall of wagons, leaving the battle a bloody draw. Both sides counted heavy losses, including Profuturus who was slain on the battlefield.[41][42]

After the battle the Romans retreated to Marcianople. The Goths of Fritigern spent seven days within their wagon fort before moving out. Frigeridus destroyed and enslaved a band of marauding Goths under Farnobius and sent the survivors to Italy. In the fall, Richomeres returned to Gaul to collect more troops for the next year's campaign. Valens meanwhile sent magister equitum Saturninus to Thrace to linkup with Traian. Saturninus and Traian erected a line of forts in the Haemus passes to block the Goths. The Romans hoped to weaken the enemy with the rigors of winter and starvation, and then lure Fritigern into open battle on the plains between the Haemus mountains and the Danube to finish him off. The Goths, once again hungry and desperate, repeatedly tried to break through the passes but were repulsed each time. Fritigern then enlisted the aid of mercenary Huns and Alans, who boosted his strength. Saturninus, realizing he could no longer hold the passes against them, abandoned the blockade and retreated. The Goths were thus free to raid anew, reaching as far as the Rhodope Mountains and the Hellespont.[43][44]

| “ | Then there were to be seen and to lament acts most frightful to see and to describe: women driven along by cracking whips, and stupefied with fear, still heavy with their unborn children, which before coming into the world endured many horrors; little children too clinging to their mothers. Then could be heard the laments of high-born boys and maidens, whose hands were fettered in cruel captivity. Behind these were led last of all grown-up girls and chaste wives, weeping and with downcast faces, longing even by a death of torment to forestall the imminent violation of their modesty. Among these was a freeborn man, not long ago rich and independent, dragged along like some wild beast and railing at thee, Fortune, as merciless and blind, since thou hadst in a brief moment deprived him of his possessions, and of the sweet society of his dear ones; had driven him from his home, which he saw fallen to ashes and ruins, and sacrificed him to a bloody victor, either to be torn from limb to limb or amid blows and tortures to serve as a slave.[45] | ” |

Archaeology finds in this region and dated to this period reveal Roman villas with signs of abandonment and deliberate destruction.[46] The devastation forced Valens to officially reduce taxes on the populations of Moesia and Scythia.[47]

378: The Battle of Adrianople

Valens finally extracted himself from the Eastern front, after granting many concessions to the Persians, and arrived with most of his army in Constantinople in the 30 May, 378. His entry into the city caused small riots against him.[48][49][50] According to the Historia Ecclesiastica of Socrates Scholasticus, the citizens of the capital accused Emperor Valens of neglecting their defense, exposing them to the raids of the Goths who now threatened Constantinople itself, and urged him to leave the city and confront the invaders with battle instead of continuing to delay.[51] Valens left the city after twelve days and moved with his army to his imperial villa Melanthias, west of Constantinople, on 12 June. There he distributed pay, supplies, and speeches to his soldiers to boost morale.[52][53][54]

Blaming Traian for the bloody draw at The Willows, Valens demoted him and appointed Sebastianus, who had arrived from Italy, to command and organize the Eastern Roman army. Sebastianus set out with a small force, drawn from the Emperor's own Scholae Palatinae,[n 3] to engage separated Gothic raiding bands. He went first to Adrianople and, such was the fear of the roving Goths, the city needed much persuasion to open its gates to him. After this, Sebastianus scored a few small victories. In one instance, he waited until nightfall to ambush a sleeping Gothic warband along the river Hebrus and slaughtered most of them. The loot Sebastianus brought back was, according to Ammianus, too much for Adrianople to hold. Sebastianus' success convinced Fritigern to recall his raiding parties to the area of Cabyle, lest they be picked off piecemeal.[56][57]

Western Roman Emperor Gratian had meant to join up with Valens' army, but events in the West detained him. First there was an invasion by the Lentienses into Gaul in February 379, which Gratian defeated.[58] Then intelligence came from the other side of the Rhine warning of barbarian preparations for more invasions. This forced Gratian to preemptively cross the river himself and bring the situation under control, and he successfully defeated the Alemanni. This took time, however, and it wasn't until August that Gratian sent a message declaring his victories and his imminent arrival. Valens, who had been impatiently waiting since June for the Western Roman army, was envious of the glory of his nephew and that of Sebastianus, so when he heard that the Goths were moving south towards Andrianople, Valens decamped his army and marched there to head them off. Roman scouting erroneously reported that the Goths, who were seen raiding near Nika, numbered only 10,000 fighting men. Around August 7, Richomeres returned from the West with the Western armies' advanced guard and a new message: Gratian was nearing the Succi pass which led to Andrianople, and he advised his uncle to wait for him. Valens called a council of war to decide the issue. According to Ammianus, Sebastianus advocated for an immediate assault upon the Goths, and that Victor cautioned to wait for Gratian. According to Eunapius, Sebestianus said they should wait. In any case, the council and Valens decided to attack immediately, egged on by court flatterers of the easy victory to come.[59][60]

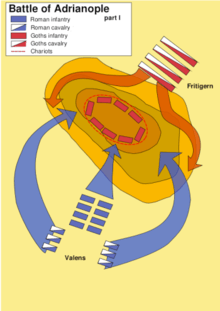

The Goths sent envoys led by a Christian priest to the Romans to negotiate on the night of August 8. With them Fritigern sent two letters. The first stipulated that the Goths only wanted lands in Thrace and in exchange would ally themselves to the Romans. The second letter, privately addressed to Valens, said that Fritigern truly wanted peace, but the Romans would have to stay mobilized so that he could enforce the peace on his own people. Whether Fritigern was earnest or not is unknown, as Valens rejected the proposal. On the morning of August 9, Valens left his treasury, imperial seal, and civilian officials in Adrianople and marched north to engage the Goths. At around two in the afternoon the Romans came within sight of the Gothic wagon fort. Unlike the Romans, the Goths were well rested, and the two sides drew up into battle formations. Fritigern sent more peace envoys, and had long since sent for the aid of the Greuthungi cavalry under Alatheus and Saphrax who were separated from the main Gothic body. These remained undetected by Roman scouts.[62][63][64]

The Eastern Roman army withered under the hot summer sun, and the Goths lit fires to blow smoke and ash into the Roman formations. Valens reconsidered the peace offer, and was preparing to send Richomeres to meet with Fritigern when two Roman elite Scholae Palatinae units, the Scutarii under Cassio and the Sagittarii under Bacurius, engaged the Goths without orders. This forced the Battle of Adrianople to begin. As the armies engaged, the Greuthungi and Alan cavalry arrived and swung the battle in favor of the Goths. The Roman left flank was surrounded and destroyed, and a rout began all along the lines which became a bloodbath for the Roman forces. They were so tightly packed they could not maneuver, and some could not lift their arms at all. Few managed to run.[65][66][67]

| “ | And so the barbarians, their eyes blazing with frenzy, were pursuing our men, in whose veins the blood was chilled with numb horror: some fell without knowing who struck them down, others were buried beneath the mere weight of their assailants; some were slain by the sword of a comrade; for though they often rallied, there was no ground given, nor did anyone spare those who retreated. Besides all this, the roads were blocked by many who lay mortally wounded, lamenting the torment of their wounds; and with them also mounds of fallen horses filled the plains with corpses. To these ever irreparable losses, so costly to the Roman state, a night without the bright light of the moon put an end.[68] | ” |

Sebastianus, Traian, tribune Aequitius, and thirty-five senior officers had been slain, while Richomeres, Victor, and Saturninus had escaped. Two-thirds of the Eastern Roman army lay dead upon the field.[69] There are conflicting stories as to what happened to the Emperor himself. One claims that he was wounded and dragged off the field by some of his men to a farmhouse. The Goths approached it and were shot at with arrows, which caused the Goths to burn it down with the Emperor inside. The other report states Valens was slain in combat on the field with his army. Whatever happened, his body was never found.[70]

The Goths, invigorated by their incredible victory, besieged Adrianople, but the city resisted. Its walls were strengthened, huge stones were placed behind the gates, and arrows, stones, javelins, and artillery rained down upon the attackers. The Goths lost men but made no progress. So they resorted to trickery: they ordered some Roman traitors to pretend to be fleeing from the Goths and infiltrate the city, where they were to set fires to allow the Goths, while the citizens were busy putting the fires out, to attack the undefended walls. The plan did not work. The Roman traitors were welcomed into the city, but when their stories did not match, they were imprisoned and tortured. They confessed to the trap and were beheaded. The Goths launched another assault, but it too failed. With this final defeat, the Goths gave up and marched away.[71] They together with some Huns and Alans went first to Perinthus and then to Constantinople. There they were fended off in the small battle of Constantinople with the help of the city's Arab garrison. At one moment, an Arab dressed only in a loincloth rushed forward against the Goths, slit one of their throats and sucked out the blood. This terrified the Goths, and combined with the immense size of the city and its walls, they decided to march off once again to plunder the countryside.[72][73]

With Valens dead, the Eastern Roman Empire had to operate without an Emperor. The magister militum of the East, Julius, feared the Gothic populations elsewhere in the Eastern Roman Empire, both civilians and those Goths serving within army units across the Empire. After the events of Adrianople, they could ally themselves to Fritigern and spread the crisis to even more provinces. Julius therefore had those Goths near the frontier lured together and massacred. By 379, word reached the Goths in the interior provinces of the massacres, and some rioted, especially in Asia Minor. The Romans put down the riots and slaughtered the Goths in those places as well, both innocent and guilty.[74][n 4]

379-382: Theodosius I and the end of the war

For the events of the Gothic War between 379 and 382, there are few sources, and accounts become more confused, especially concerning the rise of Theodosius I as the new Eastern Roman Emperor. Theodosius, who had been born in Hispania, was the son of a successful general. Theodosius himself had been dux Moesiae and campaigned in the eastern Balkans against the Sarmatians in 374. But in 376, his father fell victim to court intrigue following the death of Western Roman Emperor Valentinian I, and Theodosius decided to retire to his estates in Spain. Why then he was recalled to the East is a mystery, though undoubtedly his military experience and the critical need for it in any new emperor played a part. It seems Theodosius regained his post as dux Moesiae and was probably campaigning against the Goths by late 378. On 19 January 379, Theodosius was made emperor. Sources are silent on how this happened. Whether Gratian initiated Theodosius' elevation himself, or the surviving army in the East forced Gratian to accept Theodosius as his colleague, is unknown. Whatever the cause, Gratian did acknowledge Theodosius as his co-emperor but promptly left for the West to deal with the Alemanni. Gratian offered little help to Theodosius for dealing with the Goths, outside of giving him control of the Western imperial dioceses of Dacia and Macedonia.[76][77][78]

Theodosius set about recruiting a new army at his headquarters in Thessalonica.[79] Farmers were drafted and barbarian mercenaries from beyond the Danube were bought. The drafting of farmers created much resentment. Some mutilated their own thumbs, but many more hid themselves or deserted with the help of landowners, who were not pleased with losing their workers to the army. Theodosius responded with many harsh laws punishing those who hid deserters and rewarding those who turned them in. Even those who mutilated themselves were still forced into the Roman military.[80]

Theodosius' general Modares, a Goth himself, won a minor victory against Fritigern. Even small victories such as these were massively lauded by imperial propagandists; there are records of victory celebrations equaling half that of the previous seven decades combined. Theodosius needed victories and needed to be seen as dealing with the Gothic crisis.[81]

In 380, the Goths split.[n 5] The Greuthungi went to Illyricum and invaded the Western province of Pannonia. What happened is again disputed; they were either defeated by Gratian's forces, or they peaceably signed a deal that settled them in Pannonia. The Thervings went south into Macedonia and Thessaly. Theodosius with his new army marched to meet them, but filled with unreliable barbarians and raw recruits, it melted away. The barbarian soldiers joined Fritigern and many Romans deserted. With victory the Thervings were free to force the local Roman cities in this new region to pay them tribute. It was then that the Western Roman Empire finally offered some help. Having ended the Gothic invasion of Pannonia, Gratian met Theodosius at Sirmium, and Gratian directed his generals Arbogast and Bauto to help drive the Goths back into Thrace, which they successfully accomplished by the summer of 381. Theodosius meanwhile left for Constantinople, where he stayed. After years of war, the defeat of two Roman armies, and still locked in stalemate, peace negotiations were opened.[83][84][85]

Peace and consequences

Richomeres and Saturninus conducted the negotiations for the Romans, and peace was declared on 3 October 382.[86] By then, the Gothic commanders from Adrianople were gone; Fritigern, Alatheus, and Saphrax are never again mentioned in the ancient histories, and their ultimate fates are unknown. Speculation ranges from death in battle to overthrown as the price for peace.[87][88]

In the peace, the Romans recognized no overall leader of the Goths, and the Goths were nominally incorporated into the Roman Empire. The Romans gained a military alliance with them as foederati: the Goths would be drafted into the Roman army, and in special circumstances could be called upon to field full armies for the Romans. What differed from established Roman practice was that the Goths were given lands inside the Roman Empire itself, in the provinces of Scythia, Moesia, and possibly Macedonia, under their own authority and were not dispersed. This allowed them to stay together as a unified people with their own internal laws and cultural traditions. To seal the agreement, Theodosius threw the Goths a large feast.[89][90]

Themistius, a Roman orator and imperial propagandist, while acknowledging that the Goths could not be militarily defeated, sold the peace as a victory for the Romans who had won the Goths over to their side and turned them into farmers and allies. He believed that in time the barbarian Goths would become steadfast Romans themselves like the barbarian Galatians had before them.[91]

| “ | For just suppose that this destruction was an easy matter and that we possessed the means to accomplish it without suffering any consequences, although from past experience this was neither a foregone nor likely conclusion, nevertheless just suppose, as I said, that this solution lay within our power. Was it then better to fill Thrace with corpses or with farmers? To make it full of tombs or living men? To progress through a wilderness or a cultivated land? To count up the number of the slaughtered or those who till the soil? To colonize it with Phrygians and Bithynians perhaps, or to live in harmony with those we have subdued.[92][93] | ” |

| “ | All that [military] ingenuity of ours has proved useless; only your [Theodosius'] advice and your judgment provided an invincible resistance, and the victory you won through these inner resources of yours was finer than it would have been had you prevailed by arms. For you have not destroyed those who wronged us, but appropriated them. You did not punish them by seizing their land, but have acquired more farmers for us. You did not slaughter them like wild beasts, but charmed away their savagery just as if someone, after trapping a lion or a leopard in nets, were not to kill it but to accustom it to being a beast of burden. These fire-breathers, harder on the Romans than Hannibal was, have now come over to our side. Tame and submissive, they entrust their persons and their arms to us, whether the emperor wants to employ them as farmers or as soldiers.[94][95] | ” |

Despite these hopes, the Gothic War changed the way the Roman Empire dealt with barbarian peoples, both without and within. The Therving Goths would now be able to negotiate their position with Rome, with force if necessary, as a unified people inside the borders of the Empire, and would transform themselves into the Visigoths. At times they would act as friends and allies to the Romans, at other times as enemies. This change in Rome's relationship with barbarians would lead to the sack of Rome in 410.[96][97]

The Gothic War also affected the religion of the Empire. Valens had been an Arian Christian, and his death at Adrianople helped pave the way for Theodosius to make Nicene Christianity the dominant form of Christianity for the Roman people. The Goths, like many barbarian peoples, converted to Arianism.[98]

See also

- Battle of Adrianople

- Sack of Rome (410)

- Late Roman army

- Late Ancient Christianity

- Fall of the Western Roman Empire

Notes

- ↑ Peter Heather finds it unconvincing that Valens, who wanted the Goths as auxiliaries in his army, would have them disarmed.[16]

- ↑ The exact location is unknown, but it is surmised that it was between Tomi and the mouth of the Danube, or perhaps nearer to Marcianopole.[40]

- ↑ "three hundred soldiers from each legion"[55]

- ↑ Exactly what happened is disputed. Our two primary sources for the event, Ammianus and Zosimus, give differing accounts and dates. The account given here is Kulikowski's reading of the sequence of events.[75]

- ↑ The exact cause is disputed. Peter Heather speculates the split happened because the combined Gothic forces were simply too hard to feed.[82]

References

- ↑ Peter Heather, The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians, (Oxford University Press, 2006), page 146.

- ↑ Herwig Wolfram, The Roman Empire and Its Germanic Peoples, (University of California Press, 1997), page 85-86.

- ↑ Peter Heather, The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians, (Oxford University Press, 2006), page 145.

- ↑ Peter Heather, The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians, (Oxford University Press, 2006), page 152.

- ↑ Peter Heather, The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians, (Oxford University Press, 2006), page 145, 507.

- ↑ The Cambridge Ancient History Volume 13, (Cambridge University Press, 1998), page 98.

- ↑ Peter Heather, The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians, (Oxford University Press, 2006), page 152-153.

- ↑ Peter Heather, The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians, (Oxford University Press, 2006), page 153, 161.

- ↑ Peter Heather, The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians, (Oxford University Press, 2006), page 158.

- ↑ Peter Heather, The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians, (Oxford University Press, 2006), page 161.

- ↑ Peter Heather, The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians, (Oxford University Press, 2006), page 160-162.

- ↑ Peter Heather, The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians, (Oxford University Press, 2006), page 158.

- ↑ Ammianus Marcellinus, XXXI 4.

- ↑ Gibbon, Edward (1776). The History Of The Decline & Fall Of The Roman Empire. New York: Penguin. pp. 1048–1049. ISBN 9780140433937.

- ↑ Michael Kulikowski, Rome's Gothic Wars: From the Third Century to Alaric, (Cambridge University Press, 2006), page 130.

- ↑ Peter Heather, The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians, (Oxford University Press, 2006), page 509.

- ↑ Peter Heather, The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians, (Oxford University Press, 2006), page 163.

- ↑ Herwig Wolfram, The Roman Empire and Its Germanic Peoples, (University of California Press, 1997), page 82.

- ↑ Thomas Burns, Barbarians Within the Gates of Rome, Indiana University Press, 1994, page 24

- ↑ Thomas Burns, Barbarians Within the Gates of Rome, (Indiana University Press, 1994), page 24

- ↑ Michael Kulikowski, Rome's Gothic Wars: From the Third Century to Alaric, (Cambridge University Press, 2006), page 131.

- ↑ Peter Heather, The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians, (Oxford University Press, 2006), page 159.

- ↑ Peter Heather, The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians, (Oxford University Press, 2006), page 164.

- ↑ Michael Kulikowski, Rome's Gothic Wars: From the Third Century to Alaric, (Cambridge University Press, 2006), page 133.

- ↑ Thomas Burns, Barbarians Within the Gates of Rome, Indiana University Press, 1994, page 26

- ↑ Michael Kulikowski, Rome's Gothic Wars: From the Third Century to Alaric, (Cambridge University Press, 2006), page 133-134.

- ↑ Peter Heather, The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians, (Oxford University Press, 2006), page 171.

- ↑ Ammianus Marcellinus, XXXI.6.1.

- ↑ Ammianus Marcellinus, XXXI.6.

- ↑ Ammianus Marcellinus, XXXI.6.7-8. Trans. J. C. Rolfe.

- ↑ Michael Kulikowski, Rome's Gothic Wars: From the Third Century to Alaric, (Cambridge University Press, 2006), page 134.

- ↑ Michael Kulikowski, Rome's Gothic Wars: From the Third Century to Alaric, (Cambridge University Press, 2006), page 136.

- ↑ Peter Heather, The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians, (Oxford University Press, 2006), page 172-173.

- ↑ Michael Kulikowski, Rome's Gothic Wars: From the Third Century to Alaric, (Cambridge University Press, 2006), page 137.

- ↑ Thomas Burns, Barbarians Within the Gates of Rome, (Indiana University Press, 1994), page 26-27.

- ↑ Thomas Burns, Barbarians Within the Gates of Rome, Indiana University Press, 1994, page 27.

- ↑ Ammianus Marcellinus, XXXI.7.

- ↑ Michael Kulikowski, Rome's Gothic Wars: From the Third Century to Alaric, (Cambridge University Press, 2006), page 137-138.

- ↑ Peter Heather, The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians, (Oxford University Press, 2006), page 173.

- ↑ Michael Kulikowski, Rome's Gothic Wars: From the Third Century to Alaric, (Cambridge University Press, 2006), page 137.

- ↑ Michael Kulikowski, Rome's Gothic Wars: From the Third Century to Alaric, (Cambridge University Press, 2006), page 137-138.

- ↑ Ammianus Marcellinus, XXXI.7.

- ↑ Ammianus Marcellinus, XXXI.8.

- ↑ Michael Kulikowski, Rome's Gothic Wars: From the Third Century to Alaric, (Cambridge University Press, 2006), page 137-138.

- ↑ Ammianus Marcellinus, XXXI.8.7-8. Trans. J. C. Rolfe.

- ↑ Peter Heather, The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians, (Oxford University Press, 2006), page 175.

- ↑ Michael Kulikowski, Rome's Gothic Wars: From the Third Century to Alaric, (Cambridge University Press, 2006), page 138.

- ↑ Peter Heather, The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians, (Oxford University Press, 2006), page 176-177.

- ↑ Michael Kulikowski, Rome's Gothic Wars: From the Third Century to Alaric, (Cambridge University Press, 2006), page 139.

- ↑ Ammianus Marcellinus, XXXI.11.1.

- ↑ Socrates Scolasticus, Historia Ecclesiastica, IV.38.

- ↑ Michael Kulikowski, Rome's Gothic Wars: From the Third Century to Alaric, (Cambridge University Press, 2006), page 139.

- ↑ Ammianus Marcellinus, XXXI.11.1.

- ↑ Peter Heather, The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians, (Oxford University Press, 2006), page 177.

- ↑ Ammianus Marcellinus, XXXI.11.2. Trans. J. C. Rolfe.

- ↑ Michael Kulikowski, Rome's Gothic Wars: From the Third Century to Alaric, (Cambridge University Press, 2006), page 139.

- ↑ Ammianus Marcellinus, XXXI.11.

- ↑ Peter Heather, The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians, (Oxford University Press, 2006), page 177.

- ↑ Michael Kulikowski, Rome's Gothic Wars: From the Third Century to Alaric, (Cambridge University Press, 2006), page 140-142.

- ↑ Peter Heather, The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians, (Oxford University Press, 2006), page 178-180.

- ↑ Michael Kulikowski, Rome's Gothic Wars: From the Third Century to Alaric, (Cambridge University Press, 2006), page 123.

- ↑ Michael Kulikowski, Rome's Gothic Wars: From the Third Century to Alaric, (Cambridge University Press, 2006), page 139-141.

- ↑ Peter Heather, The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians, (Oxford University Press, 2006), page 177-180.

- ↑ The Cambridge Ancient History Volume 13, (Cambridge University Press, 1998), page 100.

- ↑ Michael Kulikowski, Rome's Gothic Wars: From the Third Century to Alaric, (Cambridge University Press, 2006), page 139-141.

- ↑ Peter Heather, The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians, (Oxford University Press, 2006), page 177-180.

- ↑ The Cambridge Ancient History Volume 13, (Cambridge University Press, 1998), page 100.

- ↑ Ammianus Marcellinus, XXXI.13.10-11. Trans. J. C. Rolfe.

- ↑ Michael Kulikowski, Rome's Gothic Wars: From the Third Century to Alaric, (Cambridge University Press, 2006), page 143.

- ↑ Peter Heather, The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians, (Oxford University Press, 2006), page 180.

- ↑ Ammianus Marcellinus, XXXI.15.

- ↑ Ammianus Marcellinus, XXXI.16.

- ↑ Michael Kulikowski, Rome's Gothic Wars: From the Third Century to Alaric, (Cambridge University Press, 2006), page 146.

- ↑ Michael Kulikowski, Rome's Gothic Wars: From the Third Century to Alaric, (Cambridge University Press, 2006), page 146-147.

- ↑ Michael Kulikowski, Rome's Gothic Wars: From the Third Century to Alaric, (Cambridge University Press, 2006), page 146-147.

- ↑ Michael Kulikowski, Rome's Gothic Wars: From the Third Century to Alaric, (Cambridge University Press, 2006), page 149-150.

- ↑ Gibbon, Edward (1776). The History Of The Decline & Fall Of The Roman Empire. Chapter 26.

- ↑ A. D. Lee, War in Late Antiquity: A Social History, (Blackwell Publishing, 2007), page 29.

- ↑ The Cambridge Ancient History Volume 13, (Cambridge University Press, 1998), page 101-102.

- ↑ Stephen Williams and Gerard Friell, Theodosius: The Empire at Bay, (Yale University Press, 1998), page 15-16.

- ↑ Michael Kulikowski, Rome's Gothic Wars: From the Third Century to Alaric, (Cambridge University Press, 2006), page 150-151.

- ↑ Peter Heather, The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians, (Oxford University Press, 2006), page 183.

- ↑ Peter Heather, The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians, (Oxford University Press, 2006), page 183-185.

- ↑ Michael Kulikowski, Rome's Gothic Wars: From the Third Century to Alaric, (Cambridge University Press, 2006), page 150-151.

- ↑ Peter Heather and David Moncur, Politics, Philosophy, and Empire in the Fourth Century, (Liverpool University Press, 2001), page 224.

- ↑ Peter Heather and David Moncur, Politics, Philosophy, and Empire in the Fourth Century, (Liverpool University Press, 2001), page 207.

- ↑ Peter Heather, The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians, (Oxford University Press, 2006), page 185-186.

- ↑ Michael Kulikowski, Rome's Gothic Wars: From the Third Century to Alaric, (Cambridge University Press, 2006), page 152-153.

- ↑ Peter Heather, The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians, (Oxford University Press, 2006), page 185-186.

- ↑ Michael Kulikowski, Rome's Gothic Wars: From the Third Century to Alaric, (Cambridge University Press, 2006), page 152-153.

- ↑ Peter Heather, The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians, (Oxford University Press, 2006), page 163, 186, 511.

- ↑ Peter Hearth and David Moncur, Politics, Philosophy, and Empire in the Fourth Century: Select Orations of Themistius, (Liverpool University Press, 2001), page 280.

- ↑ Themistius, Oration 16.

- ↑ Robert J. Panella, The Private Orations of Themistius, (University of California Press, 2000), page 225.

- ↑ Themistius, Oration 34.

- ↑ Michael Kulikowski, Rome's Gothic Wars: From the Third Century to Alaric, (Cambridge University Press, 2006), page 145.

- ↑ Peter Heather, The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians, (Oxford University Press, 2006), page 186, 502.

- ↑ Herwig Wolfram, The Roman Empire and Its Germanic Peoples, (University of California Press, 1997), page 87.

Sources

- Primary sources

- Ammianus Marcellinus , The History, XXXI.

- Secondary sources

- Peter Heather (2005), The Fall of the Roman Empire, ISBN 0-19-515954-3.

- Michael Kulikowski (2007), Rome's Gothic Wars, ISBN 0-521-84633-1.