Hans Hendrik

Hans Hendrik, also known as Hans Christian, native name Suersaq (c. 1834 – 11 August 1889), was a Greenlandic Arctic traveller and interpreter, born in the southern settlement of Fiskernæs.[1]

Supporting the Kane Expedition

Hendrik was hired by the American explorer Elisha Kent Kane for the 1853-55 Second Grinnell Expedition to search for the lost Franklin expedition. He established his worth in the winter of 1854, when participating in a search for four of the men who were lying frozen and disabled somewhere northwest of the ship, which was beset in the ice in Rensellaer Bay. Hendrik located their sledge track, which brought the rescue party to the men.[2] He also assisted with communication with the local Inuit, and was instrumental in hunting efforts, including tracking and finding a wounded caribou in February 1855 when the men were beginning to starve and show signs of scurvy.[3] It was due to Henrik's ability and effort that the important sledging journey to Cape Constitution was completed. For these efforts, Hendrik's agreed upon salary was two barrels of flour and fifty-two pounds of salt pork.[4]

After the Grinnell Expedition, Hendrik returned to Qeqertarsuatsiaat, in western Greenland, where he married.[4] In a report submitted by Captain Francis Leopold McClintock on 21 September 1859 near the conclusion of his own expedition in search of Franklin, it was reported by the Inut near Cape York that Hans was residing at 'Whale Sound'.[5]

Later Expedition Support

Hendrik made his second northern voyage aboard the United States under Isaac Israel Hayes' American expedition of 1860-1861. At the end of August 1860, Hayes touched at Cape York and picked up Hans, his wife, and child. On 21 December, Hans and Sonntag began their ice journey, from which Sonntag did not return, after which Hans eventually reached an Inuit settlement, saving his own life. The ship reached to Upernavik on 15 August 1861, near which Hendrik and his small family would remain for the next three years. Following that, they returned to Fiskernaes.[1]

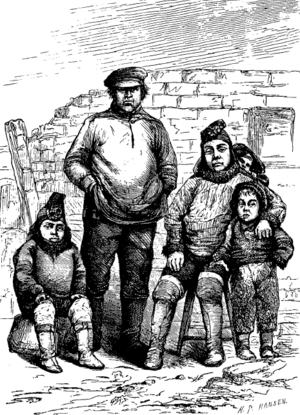

Hendrik's third journey, aboard the Polaris (1871-1873), was as part of the American expedition led by Charles Francis Hall under Captain Buddington. Hans joined the voyage, along with his wife and four children (Augustina, Tobias, Sophia, and Charlie Polaris). Hall died during the voyage of apoplexy on 8 November 1871. Hendrik was among the party left behind after Hall's death, when the ship broke loose of the ice and failed to return. During the party's six-month drift on a gradually-shrinking icefloe, Hendrik and the Canadian Inuk Ebierbing managed to provide food for the entire party; they were eventually picked up by a sealer in April 1873. Following this journey, Hendrik made a trip to America, including visits to Washington D.C. and New York, before returning home to Fiskernaes.[1]

Hendrik's last sea voyage was under George Strong Nares (Alert and Discovery) in the British expedition of 1875-1876. Hendrik presumably joined the crew of the Alert at Smith's Sound before proceeding to the northernmost reaches of Greenland. The expedition encountered problems with pack ice and scurvy, spending one winter locked in the ice. Hendrik's hunting and handling of dogsleds contributed both to the exploration and the survival and ultimate rescue of the most of the crew.[1]

Hendrik retired from expedition support and worked as boatswain and laborer at the Greenland settlements. His arctic journeys made him wealthy by the standards of his community.

Legacy

He is the first Inuk to publish an account of his Arctic explorations. Hans Island and Hendrik Island are named after him.

Notes

References

- Mowat, Farley (1967). The Polar Passion: The Quest for the North Pole. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart Limited.

Further reading

- Memoirs of Hans Hendrik, the Arctic traveller, serving under Kane, Hayes, Hall and Nares, 1853–1876, by himself — translated by Henry Rink, Trübner & Co, London, 1878.