Holkham

| Holkham | |

Holkham |

|

| Area | 23.92 km2 (9.24 sq mi) |

|---|---|

| Population | 220 (2011)[1] |

| – density | 9/km2 (23/sq mi) |

| OS grid reference | TF892438 |

| – London | 131 miles |

| Civil parish | Holkham |

| District | North Norfolk |

| Shire county | Norfolk |

| Region | East |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | WELLS-NEXT-THE-SEA |

| Postcode district | NR23 |

| Dialling code | 01328 |

| Police | Norfolk |

| Fire | Norfolk |

| Ambulance | East of England |

| EU Parliament | East of England |

Coordinates: 52°57′32″N 0°48′57″E / 52.9588°N 0.8159°E

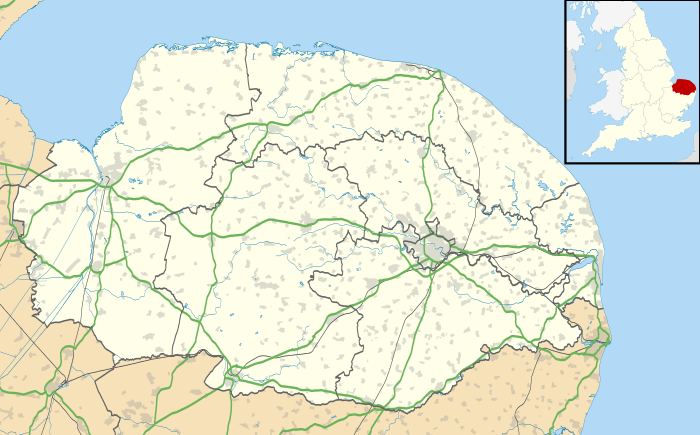

Holkham is a village and civil parish (including Quarles) in the north-west of the county of Norfolk, England. Besides the small village, the parish includes the major stately home and estate of Holkham Hall and an attractive beach at Holkham Gap. The three lie at the centre of the Holkham National Nature Reserve.

Geography

The parish has an area of 23.92 km2 (9.24 sq mi) and in the 2001 census had a population of 236 in 104 households. For the purposes of local government, the parish falls within the district of North Norfolk.[2]

The village of Holkham is located on the coast road (the A149) between Wells-next-the-Sea and Burnham Overy Staithe.[3] At one time the village was a landing with access to the sea via a tidal creek to the harbour at Wells. The creek succumbed to land reclamation, much of which created the grounds of the estate, starting in 1639 and ending in 1859 when the harbour at Wells was edged with a sea wall. The land west of the wall was subsequently turned to agricultural uses. Aerial photographs show traces of the creek in the topsoil, and the lake to the west of the hall appears to be based on a remnant of it. Now the village serves principally as the main entrance to the hall and deer park, and to Lady Anne's Drive which leads to the beach. Among the houses of the village are several estate-owned businesses, including a hotel ('The Victoria Inn') and art gallery.

Holkham Hall is one of the principal Palladian houses of England, built for an ancestor of Thomas Coke, noted agricultural innovator and later 1st Earl of Leicester of Holkham. The hall is now the home of the 8th Earl and is surrounded by an attractive park, with herds of red and fallow deer, a lake that was once a tidal creek, several monuments and drives, and its own church. Both hall and park are open to the public.

From the main coast road Lady Anne's Drive, a toll road owned by the Holkham Estate, crosses the reclaimed salt marshes to Holkham Gap. This is a gap in pine-fringed sand dunes which form the outer coastline. From here, an uninterrupted sandy beach runs both ways to Wells and Burnham Overy Staithe. To the west of the gap was a nudist section of beach but as a result of complaints received by the estate management the provision for nudism ceased on 1 July 2013.[4]

Holkham railway station was located about halfway along Lady Anne's Drive (to the east). The railway line through to Holkham was built in 1864.[5] The line made up part of the Great Eastern Railway network, which ran from Wells-next-the-Sea station, through Holkham and on to Burnham Market railway station. The line was closed in 1952.[6]

Holkham Pines is the name of the large belt of pine trees which runs west to east inland from the beach; the eastern end is known as Wells Woods. Holkham Freshmarsh is the name which refers to the series of wet meadows which sit inland from the pine belt, and north of the A149. They are bisected by Lady Anne's Drive, which gives access to the woods and the beach. The marshes are important for their wintering population of pink-footed geese, and have been designated a National Nature Reserve.

History

Celts

The last of the ancient Celts to inhabit East Anglia were the tribe of the Iceni. They are believed responsible for the earthworks of the Roman Iron Age visible in the marsh.[7] A Roman road runs along the west side of the estate. Their provincial capital under Roman occupation was Venta Icenorum near Norwich.[8]

Anglo-Saxons

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle for the years 449–454 records the arrival of large numbers of Angles and Jutes under Hengest and Horsa, defeating the British king, Vortigern, in 455.

By about 600 the distribution of cruciform brooches, a diagnostic of Anglo-Jutish society, show that the culture had displaced the Celtic on the east coast of Britain, including coastal East Anglia. A similar displacement was true of Saxon culture in south-east Britain, diagnosed by saucer brooches. Two bands of Saxons penetrated into East Anglia, one down the rivers that empty into the Wash and the other into the centre.[9]

In the 7th century the Germanic kings of these regions were being converted to Christianity. The Anglisc or Englisc of East Anglia may already by that time have been divided into the "North Folk" and the "South Folk."[10] In 654 the Christian king of East Anglia, Anna of East Anglia, was killed in battle against the last pagan king of Mercia. So great was his Christian affirmation that his four daughters renounced the world and became saints. Numerous lives of the saints relate that the youngest, Saint Withburga, was brought up at Holkham. She later founded a Benedictine nunnery at East Dereham and was eventually buried at Ely in 743. This is the first reference to Holkham.

A church on the grounds of the estate, still used for worship, commemorates the saint. The existence of the saint is attested by the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, which for the year 798 records that the body of Wihtburga, sister of St. Aethelthryth, was found to be uncorrupted at Dereham 55 years after her death.

The Chronicle and the historian, Bede, do not state the name of Holkham. It does appear as that in the Domesday Book, 1086, which means that it must precede Middle English. The element -ham is clearly identifiable as Old English, "village, manor, home."[11] The Holk- remains unidentified. A suggestion has been made that it comes from *hoelig, "holy", in honour of the saint,[12] but it would not have been named that before she was one. The guidebook of the parish church (which is dedicated to Saint Withburga) says the area was originally called 'Wihtburgstowe' but later 'holc-ham' which the church guide translates as 'homestead in a hollow'.

Later Middle Ages and the parish church

Medieval manuscripts concerning Holkham have been edited by William Hassall and Jacques Beauroy.[13]

The parish church is just south of the coast road, hidden in the trees of the Holkham Estate. It stands on a tall circular mound – which archaeologists suggest might be man-made and possibly pre-Saxon – and is dedicated to Saint Withburga. This dedication to a Saxon saint often implies a church has Saxon origins. Excavations at Holkham have found Saxon remains near the west end which may be a tower.

Norman remains have been found incorporated into the present building which implies that the Normans expanded the Saxon building – as they did at other churches. In turn this Norman church made way for an Early English building (13th century). The tower and the western part of the south aisle date from this period. The church guidebook notes that the tower gets progressively younger as it goes up. The lower section is Early English up to the sill of the belfry windows. The belfry itself is Decorated (14th century) while the battlements and pinnacles are Perpendicular (15th to 16th century). During restoration work at least six 12th and 13th century coffin lids with foliated crosses were found on site and are now on show inside the church.

The north aisle and north transept are thought to have been added later than the 13th century as burials and parts of coffin lids were found under the foundations. The church is known to have been enlarged in the 14th century and many of the internal arches are Decorated period. By the early 18th century the church had fallen into decay but the development of Holkham Estate led to renewed interest in the church. In 1767 the Countess Dowager of Leicester put up £1,000 for its repair. She had overseen the completion of Holkham Hall after the death of the 1st Earl of Leicester in 1759.

A major renovation of the church was completed in 1869 at the expense of Juliana the wife of the 2nd Earl. This cost £9,000. She died the following year and has a striking sculpted memorial in the north chapel of the church. There are several other memorials to various members of the Coke family from whom the Earls of Leicester are descended. The unusual mausoleum in the west wall of the churchyard was built for Juliana but her body was later transferred to the family plot on the south side of the churchyard.

Media

- All the Peenemünde sequences of the 1965 film Operation Crossbow featuring German attempts to make the V-1 fly were filmed at Holkham Gap. The mass grave sequence at Holkham was filmed using male extras recruited from nearby Wells-next-the-Sea and – as a result – the film used to show at the former Wells cinema for several weeks a year during the late 1960s.

- Several parts of the 1976 film The Eagle Has Landed, starring Michael Caine, Donald Sutherland and Robert Duvall, were filmed on Holkham Beach and in the pinewoods.

- The final scenes of Shakespeare in Love (1998) were filmed on the beach.

- The music video for "Pure Shores", by All Saints, for the 2000 film The Beach, was filmed here.

- A number of beach scenes for the Avengers episode "The Town of No Return" (1965) were filmed at Holkham Gap.

- Parts of the ITV1 drama Kingdom, featuring comedian Stephen Fry, were filmed on Wells and Holkham Beaches.[14]

- 'The Duchess' starring Kiera Knightly was filmed at Holkham Hall

See also

Notes

- ↑ "Parish population 2011". Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- ↑ Office for National Statistics & Norfolk County Council (2001). "Census population and household counts for unparished urban areas and all parishes". Retrieved 2 December 2005.

- ↑ "Multimap.com". Retrieved 31 January 2007.

- ↑ http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-norfolk-22949459

- ↑ "The Victoria at Holkham – History". Archived from the original on 26 September 2006. Retrieved 1 February 2007.

- ↑ See also List of Closed Railway Stations, etc., below.

- ↑ See under External links below.

- ↑ Historical Atlas page 24.

- ↑ Historical Atlas Page 31.

- ↑ The question of the origin of Norfolk and Suffolk is like that of the origin of Holkham. The names appear with modern meanings in the Domesday Book but not in earlier sources, although some of the monastic records imply an early distinction. The etymology is not of much help as the segments from which the names are formed are exactly the same in either Old English or Old Norse: "north", "south", and "folk." There are advocates of an early, Anglo-Saxon view, and of a later, Old Norse view.

- ↑ The etymology is given under tkei in the American Heritage Dictionary.

- ↑ Stirling, page 14.

- ↑ Hassall, W.; Beauroy, J. (1993). Lordship and Landscape in Norfolk 1250–1350: The Early Records of Holkham. Oxford.

- ↑ Holkham Estate film location

Bibliography

- Falkus, Malcolm; Gillingham, John (1987). Historical Atlas of Britain. Crescent Books. ISBN 0-517-63382-5.

- Stirling, Anna Maria Diana Wilhelmina Pickering (1908). Coke of Norfolk and his Friends. London, New York: John Lane, the Bodley Head. Available Google Books.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Holkham. |

- Map sources for Holkham

- Information from Genuki Norfolk on Holkham.

- The Holkham Estate website

- DiCamillo companion guide – includes some good photos

- Holkham Camp Norfolk, roman-Britain.org

- North Norfolk History, article in the North Norfolk News.

- Place names based on a Scandinavian personal name element, Viking.no site