Host switch

In parasitology and epidemiology, a host switch (or host shift) is an evolutionary change of host specificity. All symbiotic species, such as parasites, pathogens and mutualists exhibit a certain degree of host specificity. They occur in the body (or on the body surface) of a single host species or – more often – on a limited set of host species. In the latter case, the suitable host species tend to be taxonomically related, sharing similar morphology and physiology.[1]

For example, the human immunodeficiency virus used to occur in non-human primates in West-central Africa, and have switched to humans in the early 20th century.[2][3]

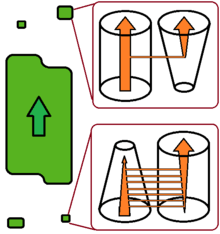

Recent studies proposed to discriminate between two different types of evolutionary changes in host specificity.[5][6]

According to this view, host switch is a sudden and accidental colonization of a new host species by a few parasite individuals that are capable to establish a new and viable population there. After the switch, the new population is more-or-less isolated from the parasite population on the donor host species. It does not affect the further fate of the conspecific parasites on the donor host, and it may finally lead to parasite speciation. It is more likely to target an increasing host population that harbours a relatively poor parasite/pathogen fauna, such as the pioneer populations of invasive species.

Contrarily, host-shift is a gradual change of the relative role of a particular host species as primary versus secondary host, in case of a multi-host parasite species. The former primary host slowly becomes a secondary host or even becomes totally abandoned, while the former secondary host becomes a new primary host species. This process is slower and more predictable, and it does not increase parasite diversity. Predictably, it more often occurs in shrinking host populations that harbours a relatively (considering the small host population size) rich parasite/pathogen fauna.

References

- ↑ Poulin, R. (2006) Evolutionary Ecology of Parasites Princeton University Press

- ↑ Sharp PM, Hahn BH (2011). "Origins of HIV and the AIDS Pandemic". Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine. 1 (1): a006841. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a006841. PMC 3234451

. PMID 22229120.

. PMID 22229120. - ↑ Faria NR, Rambaut A, Suchard MA, Baele G, Bedford T, Ward MJ, Tatem AJ, Sousa JD, Arinaminpathy N, Pépin J, Posada D, Peeters M, Pybus OG, Lemey P (2014). "The early spread and epidemic ignition of HIV-1 in human populations". Science. 346 (6205): 56–61. doi:10.1126/science.1256739.

- ↑ Reed DL, Light JE, Allen JM, Kirchman JJ (2007). "Pair of lice lost or parasites regained: the evolutionary history of anthropoid primate lice". BMC Biology. 5: 7. doi:10.1186/1741-7007-5-7. PMC 1828715

. PMID 17343749.

. PMID 17343749. - 1 2 Rozsa, L; Tryjanowski, P; Vas, Z (2015). "Under the changing climate: how shifting geographic distributions and sexual selection shape parasite diversification" (PDF). In Morand S; Krasnov B; Littlewood T (eds.). Parasite diversity and diversification: evolutionary ecology meets phylogenetics. Cambridge University Press. pp. 58–76. ISBN 9781107037656.

- 1 2 Forró B, Eszterbauer E (2016). "Correlation between host specificity and genetic diversity for the muscle-dwelling fish parasite Myxobolus pseudodispar: examples of myxozoan host-shift?" (PDF). Folia Parasitologica. 63: 019. doi:10.14411/fp.2016.019.