Humbaba

| Part of a series on |

| Ancient Mesopotamian religion |

|---|

|

|

Demigods and heroes |

| Related topics |

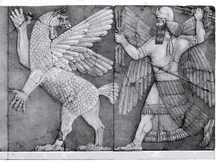

In Ancient Mesopotamian religion, Humbaba (𒄷𒌝𒁀𒁀 Assyrian spelling), also spelled Huwawa (𒄷𒉿𒉿 Sumerian spelling) and surnamed the Terrible, was a monstrous giant of immemorial age raised by Utu, the Sun.[1] Humbaba was the guardian of the Cedar Forest, where the gods lived, by the will of the god Enlil, who "assigned [Humbaba] as a terror to human beings. Gilgamesh defeated this great enemy."

Description

His face is that of a lion, "he looks at someone, it is the look of death."[2] "Humbaba's roar is a flood, his mouth is death and his breath is fire! He can hear a hundred leagues away any [rustling?] in his forest! Who would go down into his forest!"[3] In various examples, his face is scribed in a single coiling line like that of the coiled entrails of men and beasts, from which omens might be read.[4] ċċċ Another description from Georg Burckhardt translation of Gilgamesh says, "he had the paws of a lion and a body covered in thorny scales; his feet had the claws of a vulture, and on his head were the horns of a wild bull; his tail and phallus each ended in a snake's head."

Yet another description in a newly discovered tablet in Sulaymaniyah is somewhat positive about Humbaba:

"Where Humbaba came and went there was a track, the paths were in good order and the way was well trodden ... Through all the forest a bird began to sing: A wood pigeon was moaning, a turtle dove calling in answer. Monkey mothers sing aloud, a youngster monkey shrieks: like a band of musicians and drummers daily they bash out a rhythm in the presence of Humbaba."In this version of the story, Humbaba is beloved of the gods and a kind of king in the palace of the forest. Monkeys are his heralds, birds his courtiers, and his entire throne room breathes with the heady aroma of cedar resin.[5]

The tablet goes on to portray Gilgamesh as an aggressor who destroys a forest unnecessarily, and his death is lamented by Enkidu.

Demise

Humbaba is first mentioned in Tablet II of the Epic of Gilgamesh: after Gilgamesh and Enkidu become friends following their initial fight, they set out on an adventure to the Cedar Forest beyond the seventh mountain range, to slay Humbaba (Huwawa): "Enkidu," Gilgamesh vows, "since a man cannot pass beyond the final end of life, I want to set off into the mountains, to establish my renown there."[2] Gilgamesh tricks the monster into giving away his seven "radiances" by offering his sisters as wife and concubine. When Humbaba's guard is down, Gilgamesh punches him and captures the monster. Defeated, Humbaba appeals to a receptive Gilgamesh for mercy, but Enkidu convinces Gilgamesh to slay Humbaba. In a last effort, Humbaba tries to escape but is decapitated by Enkidu, or in some versions by both heroes together; his head is put in a leather sack, which is brought to Enlil, the god who set Humbaba as the forest's guardian. Enlil becomes enraged upon learning this and redistributes Humbaba's seven splendors (or in some tablets "auras"). "He gave Humbaba's first aura to the fields. He gave his second aura to the rivers. He gave his third aura to the reed-beds. He gave his fourth aura to the lions. He gave his fifth aura to the palace (one text has debt slaves). He gave his sixth aura to the forests (one text has the hills). He gave his seventh aura to Nungal."[6] No vengeance was laid upon the heroes, though Enlil says, "He should have eaten the bread that you eat, and should have drunk the water that you drink! He should have been honored."

As each gift was given by Gilgamesh, he received a "terror" (= "radiance") in exchange, from Humbaba. The seven gifts successively given by Gilgamesh were:[7]

- his sister, Ma-tur,

- (a gap in the text),

- eca-flour,

- big shoes,

- tiny shoes,

- semi-precious stones, and

- a bundle of tree-branches.

While Gilgamesh thus distracts and tricks this spirit of the cedar forest, the fifty unmarried young men he has brought on the adventure are felling cedar timber, stripping it of its branches and laying it "in many piles on the hillside," ready to be taken away. Thus the adventure reveals itself in the context of a timber raid, bringing cedar wood to timberless Mesopotamia.

As his death approaches, and Gilgamesh is oppressed with his own mortality, the gods remind him of his great feats: "…having fetched cedar, the unique tree, from its mountains, having killed Humbaba in the forest…"[8]

The iconography of the apotropaic severed head of Humbaba, with staring eyes, flowing beard and wild hair, is well documented from the First Babylonian Dynasty, continuing into Neo-Assyrian art and dying away during the Achaemenid rule. The severed head of the monstrous Humbaba found a Greek parallel in the myth of Perseus[9] and the similarly employed head of Medusa, which Perseus placed in his leather sack.[10] Archaic Greek depictions of the gorgoneion render it bearded, an anomaly in the female Gorgon. Judith McKenzie detected Humbaba heads in a Nabatean tomb frieze at Petra.[11]

See also

References

- ↑ "Utu, I never knew a mother who bore me, nor a father who brought me up! I was born in the mountains—you brought me up!" (Gilgamesh and Huwawa, version A), or "The mother who bore me was in a cave in the mountains. The father who engendered me was a cave in the hills. Utu left me to live all alone in the mountains!" (Gilgamesh and Huwawa, version B)

- 1 2 Gilgamesh and Huwawa, version A

- ↑ Epic of Gilgamesh, Tablet II.

- ↑ Stephanie Dalley, Myths From Mesopotamia, (Oxford University Press) 1989; S. Smith, "The face of Huwawa," Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 26 (1926:440–42).

- ↑

- ↑ Nungal, the goddess of prisoners.

- ↑ (lines 140–150)

- ↑ "The death of Gilgamesh" Segment F from Me-Turan

- ↑ Noted at an early date by Clark Hopkins, "Assyrian elements in the Perseus–Gorgon story," American Journal of Archaeology 38 (1934:341-ff).

- ↑ Judith McKenzie, A.T. Reyes and A. Schmidt-Colinet, "Faces in the rock at Petra and Medain Saleh," Palestine Exploration Quarterly 130 (1998) 37, 39 with references. Not all decapitation scenes are identifiable as Gilgamesh and Humbaba: in 1928 C. Opfer claimed to find only one (Opfer, "Der Tod des Humbaba," Altorientalische Forschungen 5 (1928:207ff).

- ↑ Judith S. McKenzie, "Keys from Egypt and the East: Observations on Nabataean Culture in the Light of Recent Discoveries" Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, No. 324, Nabataean Petra (November 2001:97–112) especially p 107f.