Inner Mongolian People's Party

Inner Mongolian People's Party | |

|---|---|

| Chairman | Temtsiltu Shobtsood |

| General Secretary | Oyunbilig |

| Founded | 23 March 1997 |

| Headquarters | Princeton, New Jersey, United States |

| Ideology | Southern Mongolia independence and Conservatism |

| Party flag | |

| |

| Website | |

| http://www.innermongolia.org | |

The Inner Mongolian People's Party, or IMPP (Mongolian: Öbür mongγul-un arad-un nam;[1] pinyin: nèiměnggǔ rénmín dǎng, or 内人党, pinyin: nèiréndǎng), is an Inner Mongolian secessionist movement. The party was started in 1997 in Princeton, New Jersey. Citing the abuses of the Chinese government against Mongols during the Cultural Revolution, the goal of the party is to establish an independent state of Inner Mongolia; the potential for unification with the existent nation of Mongolia is beyond the current scope of party goals.

Establishment

The Inner Mongolian People's Party (IMPP), Mongolian: Öbür mongγul-un arad-un nam, Chinese: 内蒙古人民党, or 内人党, pinyin: Nèiměnggǔréndǎng or Nèiréndǎng, was established on March 23, 1997 in Princeton, New Jersey with the goal of creating an independent state of Inner Mongolia.[2] Another reason for the creation of the IMPP is that some of the Inner Mongolian people still have many unaddressed grievances dating back to the atrocities committed during Cultural Revolution. They believe that the Chinese government has not been held accountable or acknowledged their wrongdoings.[3] The re-unification of Inner Mongolia and Mongolia is not currently within the “scope” of the IMPP as their current primary focus is on attaining independence for Inner Mongolia.[4]

Organization

The IMPP has a Chairman and Vice Chairman who are directly elected. The Secretary General is proposed by the Chairman and approved by the Standing Committee, who is elected by Congress Representatives. The Chairman, Vice Chairman and Secretary General all are automatically Committee members. The IMPP has branches in a few countries that are set up by the Chairman and Vice Chairman. Additionally, there is an advisory board that is made up of non-IMPP members. In March 1997, more than fifty IMPP members from Mongolia, Germany, Japan, Canada and the United States attended the first Congress of the Inner Mongolian People’s Party, which meets every four years, and acts as a decision making body. Xi Haiming was elected as Chairman, Bache was elected Vice Chairman, and Oyunbilig was elected as General Secretary.[5] Additionally, at the Congressional meeting the Constitution was passed, membership criteria agreed upon, flag design finalized and, an “Open Letter to the People of Inner Mongolia” was issued and distributed.[6] The party’s headquarters are in the United States due to the contentious relationship with the People’s Republic of China. Due to sensitivity issues and to protect IMPP members, there is limited information available to the public concerning party membership and the identities of their members.

Key members

Xi Haiming, Chairman

Xi Haiming, (Mongolian: Temtsiltu Shobtsood) was born in 1957 in Inner Mongolia. In the mid 1970s, he was actively involved in Inner Mongolian efforts to hold the Chinese government accountable to punish the people involved in the “cleansing campaign” during the Cultural Revolution. In 1981, the Chinese government implemented a policy to resettle millions of Chinese people in Inner Mongolia. Xi, as a student at the University of Inner Mongolia, became an influential student leader fighting to have the Chinese government reverse the policy and founded the Inner Mongolian League for the Defense of Human Rights.[7] Due to his activities, the Chinese authorities put him under surveillance. In 1991, many of his friends were arrested causing him to flee to Mongolia. In 1993, he was granted political asylum in Germany and currently lives there with his wife and daughter.[8]

Bache, Vice Chairman

Bache, born in 1955 in Xinjiang, used to be a member of the Communist Party of China. In 1990, he went abroad on official duty and did not return. Presently, he is a visiting scholar with the East Asian Institute at Columbia University.[9] To read his publication regarding the “cleansing of Inner Mongolians during the Cultural Revolution,” see: .

Oyunbilig, General Secretary

Oyunbilig, born in 1968 in Inner Mongolia, graduated from Beijing University in 1990 and worked for the Chinese Aerospace Department and as a business representative to Mongolia. He was actively involved in the 1989 Tiananmen Square Student Movement in Beijing. In 1995, he was granted political asylum in the U.S. and is currently living in Maryland.[10]

Membership

The only criterion for membership is that the individual accept the Constitution and is willing to actively participate in all events. According to the Constitution, members are free to withdraw their membership should they wish to do so.[11]

Constitution

The Constitution, passed at the first Congress, states the party’s main goals as “to uphold the principles of democracy and peace in fighting to end the Chinese Communist Party's colonial rule in Inner Mongolia” and the “ultimate goal is to achieve the independence of Inner Mongolia.” [12] The Constitution can be read in its entirety at: .

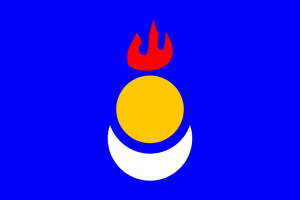

Flag Symbolism

The IMPP flag, as stipulated by their Constitution,[13] has a blue background with images of a red fire (top), a golden sun (middle), and a white moon (bottom). The blue background signifies the "Eternal Blue Heaven” (Mongolian: Monkh Khokh Tengger). The Mongols believe the spirit of the “Eternal Blue Heaven” is in all objects in the universe, especially in fire, sun and moon, which is why these three elements are represented on the flag.[14] These same images can be found on the national flag of Mongolia.

History of China-Inner Mongolia relations

Inner Mongolia is located between the Republic of Mongolia and the People's Republic of China. China was under Mongol rule when Genghis Khan toppled the Song Dynasty (960-1279) and established the Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368).[15] After the fall of the Yuan Dynasty, China was returned to Han Chinese control and stayed that way through the Ming (1368–1644) Dynasty until the Qing (1644–1911) Dynasty when China was invaded and ruled by the Manchu people. During the Qing Dynasty and the Republican period (1911–1949), Inner Mongolia was heavily populated with Han settlers. The Nationalists, who ruled during the Republican period, banned the use of the Mongolian language and were said to be more ruthless than the Japanese who later occupied Inner Mongolia. In the 1920-1940’s there were many political movements to reunite Inner Mongolia with the Mongolian People’s Republic (MPR) (that was established due to Soviet sponsorship).[16] During WWII, the Soviet-Mongolian joint army entered Inner Mongolia to fight the Japanese. The Inner Mongolians gave allegiance to the Communists to fight the Japanese in hopes of attaining their independence after the war.[17][18] However, this was not the case. On May 1, 1947 the Inner Mongolian Autonomous Region (IMAR) (Mongolian: Öbür mongγol-un öbertegen zasaqu orun, Chinese: 内蒙古自治区, pinyin: Nèi Měnggǔ Zìzhìqū) was established. IMAR also had close ties with the USSR through the Mongolian People’s Republic. The Inner Mongolians hoped that Communist Rule would be better than the previous Nationalist rulers.[19] Ulanfu was appointed by the Communist Party to rule Inner Mongolia. As Ulanfu was of Mongolian ethnicity, it was an improvement for the Inner Mongolia’s as even though they did not have independence, they were at least being ruled by an ethnic Mongolian. Ulanfu was an early Communist activist, studied in the USSR and joined the Red Army in Yenan. Mao Zedong, at first, trusted and supported him.[20] For the next two decades, Ulanfu worked to balance the needs of the Inner Mongolian people and the demands of the Communist Party. In the 1950s, Ulanfu’s balancing act became more difficult with the Communist Party’s land, social and political reforms aimed to tie Inner Mongolia closer to China. Ulanfu struggled to preserve Inner Mongolian interests as well as the Central Government’s as tensions increased.[21] His efforts to adapt the reforms to the needs of the local population lead to his downfall and made him the target of Maoists.[22] In the 1960s, as the Cultural Revolution was coming into fruition, China and the USSR cut ties. Anyone with connections to the USSR was seen as a potential political enemy. In 1966, Ulanfu due to his previous close connection to the USSR, was to become one of the most senior victims of the Cultural Revolution when he was denounced and dismissed for alleged anti-party activities. He disappeared until after Mao’s death when he was appointment Vice Premier in a wave of rehabilitations of party officials [23] who fell victim to the witch hunts during the Cultural Revolution.

Cultural Revolution: Purge of the IMPP

During the Chinese Cultural Revolution (CR) (1966–1976), Chairman Mao Zedong in his quest to reassert his own power, Socialism, and rid Chinese society of traditional, capitalist and cultural elements, went after every person that he deemed a capitalist or disloyal to the Communist Party. Many minority groups including the Inner Mongolians, Tibetans and Uyghurs (people from Xinjiang) were targeted. Inner Mongolia, although far from Beijing was not unaffected by the CR. The treatment of the Inner Mongolians from 1967-1969 was especially brutal resulting in 22,000 known deaths and 300,000 known injuries. After Ulanfu was ousted, chaos ensued with multiple clashes between students and the army. Zhou Enlai attempted to deal with what was being called the “IMAR problem” and chaired meetings between the local groups and central leaders trying to ease the situation. The result was that a senior Han Chinese General, Teng Haiqing, was put in place in April 1967.[24]

Under General Teng’s leadership, the already tense situation erupted. The Mongolian language was banned from publications and an office, run by a Mongolian, Ulanbaagen, was set up to, “root out the IMPP.” Ulanbaagen had to produce a list of people under suspicion. In 1969, Beijing acknowledged that the situation in Inner Mongolia needed to be controlled. General Teng was reprimanded and forced to apologize as to not let the government lose face. After the Cultural Revolution came to an end, the episode in Inner Mongolia was blamed on the Gang of Four [25] and the Lin Biao Clique. The Cultural Revolution affected almost every person of Mongolian descent and set the stage for the future creation of the IMPP.

See also

References

- ↑ Inner Mongolian People's Party

- ↑ http://www.innermongolia.org/english/index.html

- ↑ Brown, Kerry. “THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION IN INNER MONGOLIA 1967–1969: THE PURGE OF THE “HEIRS OF GENGHIS KHAN.” Asian Affairs, vol. XXXVIII, no. II, July 2007.

- ↑ http://www.innermongolia.org/english/index.html

- ↑ http://www.smhric.org/news_39.htm

- ↑ http://www.smhric.org/news_39.htm

- ↑ http://www.innermongolia.org/english/index.html

- ↑ http://www.innermongolia.org/english/index.html

- ↑ http://www.smhric.org/news_39.htm

- ↑ http://www.innermongolia.org/english/index.html

- ↑ http://www.innermongolia.org/english/cst.htm

- ↑ http://www.smhric.org/news_39.htm

- ↑ http://www.crwflags.com/fotw/flags/cn-impp.html#impp

- ↑ http://www.google.com/search?q=mongolian+flag&hl=en&client=safari&rls=en&prmd=imvns&tbm=isch&tbo=u&source=univ&sa=X&ei=VaWdTsuaNYXX0QG4qujDCQ&ved=0CDEQsAQ&biw=1267&bih=609

- ↑ http://www.innermongolia.org/english/cst.htm

- ↑ http://www.crwflags.com/fotw/flags/cn-impp.html#impp

- ↑ Brown, Kerry. “THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION IN INNER MONGOLIA 1967–1969: THE PURGE OF THE “HEIRS OF GENGHIS KHAN.” Asian Affairs, vol. XXXVIII, no. II, July 2007.

- ↑ http://ehis.ebscohost.com/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=daeab1d6-741c-495f-b861-c234517a7b39%40sessionmgr113&vid=2&hid=115

- ↑ Brown, Kerry. “THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION IN INNER MONGOLIA 1967–1969: THE PURGE OF THE “HEIRS OF GENGHIS KHAN.” Asian Affairs, vol. XXXVIII, no. II, July 2007

- ↑ Brown, Kerry. “THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION IN INNER MONGOLIA 1967–1969: THE PURGE OF THE “HEIRS OF GENGHIS KHAN.” Asian Affairs, vol. XXXVIII, no. II, July 2007

- ↑ Brown, Kerry. “THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION IN INNER MONGOLIA 1967–1969: THE PURGE OF THE “HEIRS OF GENGHIS KHAN.” Asian Affairs, vol. XXXVIII, no. II, July 2007

- ↑ Brown, Kerry. “THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION IN INNER MONGOLIA 1967–1969: THE PURGE OF THE “HEIRS OF GENGHIS KHAN.” Asian Affairs, vol. XXXVIII, no. II, July 2007

- ↑ Brown, Kerry. “THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION IN INNER MONGOLIA 1967–1969: THE PURGE OF THE “HEIRS OF GENGHIS KHAN.” Asian Affairs, vol. XXXVIII, no. II, July 2007

- ↑ Brown, Kerry. “THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION IN INNER MONGOLIA 1967–1969: THE PURGE OF THE “HEIRS OF GENGHIS KHAN.” Asian Affairs, vol. XXXVIII, no. II, July 2007

- ↑ Brown, Kerry. “THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION IN INNER MONGOLIA 1967–1969: THE PURGE OF THE “HEIRS OF GENGHIS KHAN.” Asian Affairs, vol. XXXVIII, no. II, July 2007