James M. Cox

| James M. Cox | |

|---|---|

| |

| 46th and 48th Governor of Ohio | |

|

In office January 13, 1913 – January 11, 1915 | |

| Lieutenant | W. A. Greenlund |

| Preceded by | Judson Harmon |

| Succeeded by | Frank B. Willis |

|

In office January 8, 1917 – January 10, 1921 | |

| Lieutenant |

Earl D. Bloom Clarence J. Brown |

| Preceded by | Frank B. Willis |

| Succeeded by | Harry L. Davis |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Ohio's 3rd district | |

|

In office March 4, 1909 – January 12, 1913 | |

| Preceded by | J. Eugene Harding |

| Succeeded by | Warren Gard |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

James Middleton Cox March 31, 1870 Jacksonburg, Ohio |

| Died |

July 15, 1957 (aged 87) Kettering, Ohio |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse(s) | Mayme Simpson Harding Cox, Margaretta Parker Blair Cox |

| Children | Four |

| Religion | United Brethren in Christ |

| Signature |

|

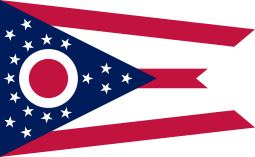

James Middleton Cox (March 31, 1870 – July 15, 1957) was the 46th and 48th Governor of Ohio, U.S. Representative from Ohio and Democratic candidate for President of the United States in the election of 1920. He founded the chain of newspapers that continues today as Cox Enterprises, a media conglomerate.

Early life and career

Cox was born on a farm near the tiny Butler County, Ohio, village of Jacksonburg, the youngest son of Gilbert Cox and Eliza Andrews; he had six siblings.[1] He was educated in a one-room school until the age sixteen.[2] After his parents divorced, he moved with his mother in 1886 to Middletown, Ohio, where he started a journalistic apprenticeship at the Middletown Weekly Signal published by John Q. Baker. In 1892 he received a job at the Cincinnati Enquirer as a copy reader on the telegraph desk, and later started to report on spot news including the railroad news. In 1894, Cox became an assistant to Middletown businessman Paul J. Sorg who was elected to U.S. Congress, and spent three formative years in Washington, D.C. Sorg helped Cox to acquire the struggling Dayton Evening News, and Cox, after renaming it into the Dayton Daily News, turned it by 1900 into a successful afternoon newspaper outperforming competing ventures. He refocused local news, increased national, international and sports news coverage based on Associated Press wire service, published timely market quotes with stock-exchange, grain and livestock tables, and introduced several innovations including photo-journalistic approach to news coverage, suburban columns, book serializations and McClure's Saturday magazine supplement inserts, among others. Cox started a crusade against Dayton's Republican boss, Joseph E. Lowes, who used his political clout to profit from government deals. He also confronted John H. Patterson, president of Dayton's National Cash Register Co., revealing facts of antitrust violations and bribery.[3] In 1905, foretelling his future media conglomerate, Cox acquired the Springfield Press-Republic published in Springfield, Ohio, and renamed it, the Springfield Daily News.

In 1908, he ran for Congress as a Democrat and was elected. Cox represented Ohio in the United States House of Representatives in 1909–1913, resigning after winning election as Governor of Ohio in a three-way race gaining 41.5% of the vote.[2]

Governor of Ohio

Cox served three terms as Governor of Ohio, first, in 1913–1915 and then in 1917–1921. He presided over a wide range of measures such as laying the foundation of Ohio's unified highway system, creating no fault workers' compensation system and restricting child labor.[4] He introduced direct primaries and municipal home rule, started educational and prison reforms, and streamlined the budget and tax processes.[5]

During World War I, Cox encouraged voluntary cooperation between business, labor, and government bodies. In 1918, he welcomed constitutional amendments for Prohibition and woman suffrage.[2] Cox supported the internationalist policies of Woodrow Wilson and reluctantly supported US entry into the League of Nations.

In 1919, shortly after the Great War ended, Governor Cox backed the Ake law, introduced by H. Ross Ake, which banned the German language from being taught until the eighth grade, even in private schools. Cox claimed that teaching German was "a distinct menace to Americanism, and part of a plot formed by the German government to make the school children loyal to it."[6]

Bid for presidency

A capable and well-liked progressive reformer, Cox was nominated for the presidency by the Democratic party at the 1920 Democratic convention in San Francisco defeating A. Mitchell Palmer and William Gibbs McAdoo on the forty-fourth ballot.[7]

Cox conducted an activist campaign visiting 36 states and delivering 394 speeches mainly focusing on domestic issues, to the displeasure of the Wilsonians, who pictured the election "as a referendum on the League of Nations."[2] To fight unemployment and inflation, he suggested simultaneously lower income and business profits taxes. He promised to introduce national collective bargaining legislation and pledged his support to the Volstead Act. Cox spoke in support of Americanization to increase loyalty to the United States among immigrant population.

Despite all efforts, Cox was defeated in the 1920 presidential election by a fellow Ohioan and newspaperman, U.S. Senator Warren G. Harding of Marion. The public had grown weary of the turmoil of the Wilson years, and eagerly accepted Harding's call for a "return to normalcy." Cox's running mate was future president, then-Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt. One of the better known analyses of the 1920 election is in Irving Stone's book about defeated presidential candidates, They Also Ran. Stone rated Cox as superior in every way over Warren Harding, claiming the former would have made a much better president; the author argued that there was never a stronger case in the history of American presidential elections for the proposition that the better man lost. Of the four men on both tickets, all but Cox would ultimately become president: Harding won, and was succeeded by his running mate Calvin Coolidge after dying in office, while Roosevelt would be elected president in 1932. However, Cox would outlive all three men by several years.

During the campaign, Cox several times recorded for The Nation's Forum, a record label that made voice recordings of American political and civic leaders in 1918-1920.[8][9] Among them was the campaign speech now preserved at the Library of Congress which accused the Republicans of failing to acknowledge that President Wilson's successful prosecution of the Great War had, according to Cox, "saved civilization."[10]

Later years

After stepping down from public service, he concentrated on building a large media conglomerate, Cox Enterprises. In 1923 he acquired the Miami Daily News and the Canton Daily News. In December 1939, he purchased the Atlanta Georgian and Journal, just a week before that city hosted the premiere of Gone with the Wind.[11]:389 This deal included radio station WSB, which joined his previous holdings, WHIO in Dayton and WIOD in Miami, to give him, "'air' from the Great Lakes on the north to Latin America on the south."[11]:387

He continued to be involved in politics, and in 1932, 1936, 1940, and 1944, Cox supported and campaigned for the presidential candidacies of his former running mate Franklin D. Roosevelt. In 1933, Cox was appointed by Roosevelt to the U.S. delegation to the failed London Economic Conference.[12]

When he was seventy-six, Cox published his memoir, Journey through My Years (1946).

In 1915, Cox built a home near those of industrialists Charles Kettering and Edward Deeds in what later became Kettering, Ohio where he lived for four decades. It was constructed in the classical French-Renaissance style with six bedrooms, six bathrooms, two tennis courts, a billiards room and an in-ground swimming pool.[13] Cox named the home, Trailsend and it was there he died in 1957 after a series of strokes.[14] He is interred in the Woodland Cemetery, Dayton, Ohio.

Cox was a member of the Church of the United Brethren in Christ.

Family

Cox was married twice. His first marriage to Mayme Simpson Harding lasted from 1893 to 1912, and ended in divorce.[2] He married Margaretta Parker Blair in 1917 and she survived him.[2][15] Cox had six children, a daughter and two sons by Mayme Harding, and a son and two daughters by Margaretta Blair.[2][15] One of his daughters, Anne Cox Chambers, is still a major shareholder in Cox Enterprises. The company's headquarters is in Atlanta.

Legacy

Cox practiced a variety of trades throughout his life, being a farmer, reporter, Congressional staff member, newspaper publisher and editor, politician, elected official and finally, a regional media magnate.[16]

In Ohio Cox is remembered as a crusading publisher of the Dayton Daily News and progressive governor; the newspaper's editorial meeting room is still referred to as the Governor's Library. The James M. Cox Dayton International Airport, more commonly referenced simply as Dayton International Airport, was named for Cox as well.

Cox is credited with words, "If there is anything in the theory of reincarnation of the soul then in my next assignment, if I be given the right of choice, I will ask for the aroma of printers ink."[3]

The Cox Fine Arts Building at the Ohio Expo Center and State Fair in Columbus, Ohio, is named in honor of Cox.

See also

References

- ↑ Goodman, Rebecca (2005). This Day in Ohio History. Emmis Books. p. 217. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Cebula, James. "Cox, James Middleton". American National Biography Online. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 1 October 2015.

- 1 2 Dayton Daily News history: James M. Cox

- ↑ Stockwell, Mary (2001). Ohio Adventure. Layton, Utah: Gibbs Smith. pp. 156–157. ISBN 9781423623823. Retrieved 1 October 2015.

- ↑ James M. Cox, Ohio History Central

- ↑ Persecution of the German Language in Cincinnati and the Ake Law in Ohio, 1917-1919. Archived.

- ↑ James M. Cox, Democratic Candidate for President, Library of Congress

- ↑ Nation's Forum Recordings: 1918-1920, AuthenticHistory.com

- ↑ American leaders speak, Library of Congress

- ↑ Governor James M. Cox. The World War, Library of Congress sound recording

- 1 2 Cox, James M. (2004). Journey through my years. Macon, Ga.: Mercer University Press.

- ↑ US Delegation on Way to New York. The Free Lance-Star - May 31, 1933

- ↑ Former Cox mansion sold in cash deal, Dayton Daily News, April 27, 2015.

- ↑ James M. Cox obituary, The New York Times, 16 July 1957.

- 1 2 "James M. Cox". NNDB. Soylent Communications. Retrieved 2011-07-29.

- ↑ History of Cincinnati and Hamilton County, Ohio. Cincinnati: S. B. Nelson & Company. 1894. p. 590. Retrieved 1 October 2015.

Further reading

- James Middleton Cox Papers, Special Collections and Archives, Wright State University, Dayton, OH

- Cox, James M. (2004). Journey through my years. Macon, Ga.: Mercer University Press. ISBN 9780865549593.

- Bagby, Wesley M. The Road to Normalcy: The Presidential Campaign and Election of 1920. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1962.

- Cebula, James E. James M. Cox: Journalist and Politician. New York: Garland, 1985.

- Morris, Charles E. The Progressive Democracy Of James M. Cox. Indianapolis: The Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1920. (From Project Gutenberg, full text.)

- Warner, Hoyt L. Progressivism in Ohio, 1897-1917. Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1964.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to James M. Cox. |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: James M. Cox |

- United States Congress. "James M. Cox (id: C000835)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- Works by or about James M. Cox at Internet Archive

- 1920 Presidential Election Links

| Offices and distinctions | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||