James Pike

| James Albert Pike | |

|---|---|

| Bishop of California | |

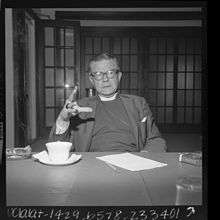

James A. Pike in 1966 | |

| Church | Episcopal Church in the United States of America |

| See | California |

| In office | 1958–66 |

| Predecessor | Bishop Karl Morgan Block |

| Successor | Bishop Kilmer Meyers |

| Orders | |

| Ordination | 1946 |

| Consecration | 1958 |

| Personal details | |

| Birth name | James Albert Pike |

| Born |

February 14, 1913 Oklahoma City, OK |

| Died |

September 9, 1969 (aged 56) Wadi Mashash, Israel |

James Albert Pike (February 14, 1913 – September 9, 1969) was an American Episcopal bishop, prolific writer, and one of the first mainline religious figures to appear regularly on television.

His outspoken, and to some, heretical views on many theological and social issues made him one of the most controversial public figures of his time. He was an early proponent of ordination of women, racial desegregation, and the acceptance of LGBT people within mainline churches. Pike was the fifth Bishop of California. Late in his life he explored psychic experimentation in an effort to contact his recently deceased son.

Early life

Pike was born in Oklahoma City on February 14, 1913. His father died when he was two, and his mother married California attorney Claude McFadden. The young Pike was a Roman Catholic and considered the priesthood; but, while attending the University of Santa Clara, he came to consider himself an agnostic. Pike earned a doctorate from Yale Law School and married Jane Alvies. He served as an attorney in Washington, D.C., for the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) during Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal era and taught Law at George Washington University. After his first marriage ended in divorce (later annulled), Pike married Esther Yanovsky. In World War II, he served with Naval Intelligence.

Conversion and early church life

After World War II, Pike and his wife joined the Episcopal Church. He entered, first, the Virginia Theological Seminary and, then, the Union Theological Seminary and began to prepare for the priesthood. He was ordained in 1946, first serving as an assistant at St. John's, Lafayette Square in Washington, D.C., then as Rector of Christ Church in Poughkeepsie, New York. He next became head of the Department of Religion and chaplain at Columbia University. He left Columbia in 1952 to become the Dean of the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, New York. Using his new position and media savvy, he vociferously opposed the local Catholic bishops over their attacks on abortionists Planned Parenthood and their opposition to birth control. He accepted an invitation to receive an honorary doctorate from Sewanee: The University of the South in Tennessee, but then publicly declined after finding that the university did not admit African Americans. An example of Pike's use of the media is how he released his letter to the New York Times before it was delivered to Sewanee's trustees: they heard the news when reporters called for reactions.[1] It was also at this time that he publicly challenged Senator Joseph McCarthy's allegation that 7,000 U.S. pastors were part of a Kremlin conspiracy; when the newly elected President Dwight D. Eisenhower backed up Pike, McCarthy and his movement began to lose their influence.[2]

In New York, Pike reached a large audience with liberal sermons and weekly television programs. Common topics included birth control, abortion laws, racism, capital punishment, apartheid, antisemitism, and farm worker exploitation.[3]

Election as bishop

He was elected as bishop coadjutor of California in 1958 and succeeded to the See a few months later, following the death of his predecessor, Karl Morgan Block. In this position, he served until 1966, when he resigned. At that point, he began to work for the Center for the Study of Democratic Institutions, a liberal, private-sector think tank.

His episcopate was marked by both professional and personal controversy. He was one of the leaders of the Protestants and Other Americans United for the Separation of Church and State movement, which advocated against John Kennedy's presidential campaign because of Catholic teachings.[4] While at Grace Cathedral, he was involved with promoting a living wage for workers in San Francisco, the acceptance of LGBT people in the church, and civil rights. He also recognized a Methodist minister as having dual ordination and freedom to serve in the diocese. Later, he ordained a woman as a first-order deacon, now known as a "transitional deacon", usually the first step in the process towards ordination in the priesthood in the Episcopal church. The ordination was not approved until after Pike's death.[5]

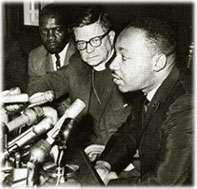

Among his notable accomplishments, Pike invited Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. to speak at Grace Cathedral in San Francisco in 1965 following his march to Selma, Alabama.

Pike's theology involved the rejection of central Christian beliefs. His writings questioned a number of widely accepted beliefs, including the virginityof Mary, the Mother of Jesus, the doctrine of Hell, and the Trinity. He famously called for "fewer beliefs, more belief."[5] Heresy procedures were begun in 1962, 1964, 1965, and 1966, each growing in intensity, but in the end the Church decided it was not in the denomination's best interest to pursue an actual heresy trial.[1]

In his personal life, Pike had been a chain-smoker and an alcoholic. His charismatic personality drew many people to him, including Maren Hackett Bergrud, with whom he developed a romantic relationship after the failure of his second marriage in 1965.

The Other Side

In 1966, Pike's son Jim took his own life in a New York City hotel room. Shortly after his son's death, Pike reported experiencing poltergeist phenomena—books vanishing and reappearing, safety pins open and indicating the approximate hour of his son's death, half the clothes in a closet disarranged and heaped up.[6] Pike led a public pursuit of various spiritualist and clairvoyant methods of contacting his deceased son to reconcile. In September 1967, Pike participated in a televised séance with his dead son through the medium Arthur Ford, who was ordained as a Disciples of Christ minister. Pike detailed these experiences in his book The Other Side.

Death

In September 1969, Pike and his third wife Diane drove into the Judean Desert. In preparation for writing a book on the historical Jesus, they wanted to have a feeling for why Jesus would have gone out into that wilderness to fast and meditate for 40 days. They were unprepared for the journey, having taken along only two Cokes and no water. When their rented car became stuck in a deep rut, the two were not able to extract it. After an hour of stressful efforts to get the car to move, they decided to walk toward Qumran, where they knew there would be water. What they did not know was that they were far south of Qumran in Wadi Mashash. After two hours of walking in the very hot sun (nearly 140 degrees Fahrenheit), Pike felt he had to rest. Diane was concerned that, without water, they would both die there so she determined to walk on to find help. After ten long hours of climbing on the walls of the canyon and stumbling along a road under construction, she came upon a camp of Arab laborers. They gave her tea to drink until the foreman came and took her to the nearest army camp. It took four days to find Pike’s body. He had tried to follow his wife and had fallen more than 60 feet down a steep canyon wall where he died. The probable date of his death is 2 September. He was buried in the Protestant Cemetery in Jaffa, Israel, on the 8th.

In literature

- James Pike was an inspiration for the character of Timothy Archer in Philip K. Dick's book, The Transmigration of Timothy Archer. They were friends, and Pike officiated at Dick's wedding to Nancy Hackett, stepdaughter of Maren Hackett (1966).[7]

- Joan Didion wrote about Pike and the building of the Grace Cathedral in her collection of essays, The White Album (1979).

- E. L. Doctorow includes Pike as a fictionalized character in his novel, City of God (2000).

Major works

- Pike, James A (1953), Beyond Anxiety, NY: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

- ——— (1963), Beyond the Law, Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Co.

- ———; Pyle, John W (1955), The Church, Politics and Society, NY: Morehouse-Gorham.

- Dentan, Robert C; Pike, James A (1949), The Holy Scriptures – The Churches Teaching, 1, NY: National Council, Protestant Episcopal Church.

- Pike, James A (1955), Doing the Truth, Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Co.

- ———, Facing the Next Day (see The Next Day below).

- ———; Pittenger, Norman (1961) [Seabury Press: Greenwich, CT, 1951], The Faith of the Church (2nd ed.), Crossroads/Seabury Press.

- ——— (1969) [1967], If This Be Heresy (paperback: Delta Book/Dell), NY: Harper & Rowe.

- ——— (1954), If You Marry Outside Your Faith, NY: Harper & Bros..

- ———; Johnson, Howard A (1956), Man in the Middle, Greenwich, CT: The Seabury Press.

- ——— (1959) [1956], Pike, James A, ed., Modern Canterbury Pilgrims (2nd, abridged ed.), NY: Morehouse-Gorham.

- ——— (1961), A New Look at Preaching, NY: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

- ——— (1968) [Dolphin Books/ Doubleday & Co: Garden City, NY, 1957], The Next Day (paperback: Facing the Next Day), MacMillan. NY.

- ———; Kennedy, Diane (1969) [Doubleday & Co: Garden City, NY, 1968], The Other Side (paperback), NY: Dell.

- ——— (1961), Our Christmas Challenge, NY: Sterling.

- ———; Krumm), John McG (1954), Roadblocks to Faith, NY: Morehouse-Gorham.

- ———; Byfield, Richard (1960), A Roman Catholic in the White House, Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Co.

- ——— (1965), Teen-Agers and Sex, Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- ——— (1964), A Time for Christian Candor, NY: Harper & Rowe.

- ——— (1966), What is This Treasure, NY: Harper & Rowe.

- ——— (1967), You and the New Morality, NY: Harper & Rowe.

Biographies

- Holzer, Hans (1970). The Psychic World of Bishop Pike. Crown Publishers. ISBN 0-5321-2255-0. OCLC 422271163.

- Robertson, David M. (2004). A Passionate Pilgrim: A Biography of Bishop James A. Pike. New York: Knopf. ISBN 0-375-41187-9. OCLC 53360781.

- Stearn, Jess (1968-01-28). "Bishop Pike's Strange Séances". This Week, The Baltimore Sun.

- Stringfellow; Towne, The Death, and Life of Bishop Pike.

- Unger, Merrill Frederick (1971). The Haunting of Bishop Pike: A Christian View of the Other Side. Wheaton, IL: Tyndale House. ISBN 0-8423-1340-0. OCLC 141366.

- Spraggett, Allen (1970) The Bishop Pike Story. New American Library

References

- 1 2 Maudlin, Michael G. "Books & Culture's Book of the Week: Be Careful What You Pray For". Christianity Today. Retrieved 2007-05-28.

- ↑ Robertson, David M (2004). A Passionate Pilgrim: A Biography of Bishop James A. Pike. New York: Knopf. ISBN 0-375-41187-9. OCLC 53360781.

- ↑ Lampen, Michael. "Bishop James Pike: Visionary or Heretic?". Tales from the Crypt. Grace Cathedral. Retrieved 2007-03-20.

- ↑ Woodward (Dec 5, 2007), "Mitt Romney is no Jack Kennedy", The New York Times.

- 1 2 Pike, James A (1967). If This Be Heresy. New York: Harper and Rowe Publishers.

- ↑ Christopher, Milbourne (1970). ESP, Seers & Psychics: What the Occult Really Is. New York: Crowell. ISBN 0-690-26815-7. OCLC 97063.

- ↑ "The author with Bishop Pike". Philip K. Dick Trust. Retrieved 2007-03-20.

External links

- James A. Pike Papers, Syracuse University.

- Nimoy, Leonard, "Bishop Pike", In Search of....

- Bibliographic directory from Project Canterbury