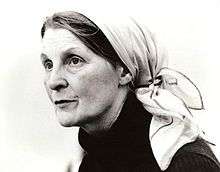

Joan Denise Moriarty

| Joan Denise Moriarty LLD | |

|---|---|

| |

| Died |

24 January 1992 Dublin, Ireland |

| Nationality | Irish |

| Occupation | ballet teacher, ballet company director |

| Years active | 1933–1992 |

| Notable work |

The Playboy of the Western World live music by The Chieftains |

| Style | classical ballet, traditional Irish dance |

Joan Denise Moriarty (died 24 January 1992) was an Irish ballet dancer, choreographer, teacher of ballet and traditional Irish dancer and musician. She was the founder of professional ballet in Ireland.

Early life

Little is known of Moriarty's early life. Her year of birth is estimated between 1910 and 1913 but no documentation has been found. The place of birth is also unknown. She was the daughter of Marion (née McCarthy), wife of Michael Augustus Moriarty, and was brought up in England, possibly Liverpool, and studied ballet until her early teens with Dame Marie Rambert. How long she was enrolled in the Rambert School is not known, as there are no records of students, but only of performers.[1] She was an accomplished Irish step-dancer and traditional musician; she lived in Liverpool with her mother from at least 1931 to 1933 and was a member of the Liverpool branch of the Gaelic League.[2] Her early dance and music awards include:

- 1931 London: Champion Irish Stepdancer of England at the London Irish Step Dance Championship. Gold Medal

- 1932 Dublin: Highly commended for solo war pipes at the Gaelic Athletic Association's Tailteann Games in Croke Park

- 1933 Killarney: Winner of the Munster Open Championship in solo war pipes

- 1933: Participated in the solo war pipes competition at the Scots Gathering and Highland Games at Morecambe and Heysham in Lancashire[3]

Return to Ireland

In the autumn of 1933 she returned with her family to their native Mallow in County Cork. In 1934 she set up her first school of dance there. From 1938 she also gave weekly classes in Cork in the Gregg Hall and Windsor School. During the 1930s she took part in the Cork Feis, annual arts competitions with a focus on traditional dance and music, competing in Irish step-dancing, war pipes and operatic solo singing. She performed on the war pipes in various public concerts and gave at least two broadcasts. In 1938 she was invited by Seán Neeson, lecturer in Irish music at University College Cork, to perform at a summer school which the Music Department organised for primary school teachers.[4]

Moriarty's mother died in February 1940; the following November she moved to Cork where she set up the Moriarty School of Dancing. The early years during the war were very difficult financially. In the early 1940s she performed with her dancers in musicals and variety shows at the Cork Opera House.[5] In 1945 the composer Aloys Fleischmann invited her to perform in his Clare's Dragoons for baritone, war pipes, choir and orchestra, which had been commissioned by the national broadcasting company, Radio Éireann, for the Thomas Davis centenary. Moriarty agreed, on condition that his Cork Symphony Orchestra would play for her Ballet Company's annual performances. This was the beginning of a lifelong collaboration.[6]

The Schools of Dance

Branches of the Moriarty School of Dance were established in Bandon, Clonmel, Fermoy, Killarney, Mallow, Tralee, Waterford, Youghal. Moriarty bequeathed her Cork school to Breda Quinn, a long-standing member of the Cork Ballet Company, who ran it with another Moriarty student, Sinéad Murphy, who created a new dance school (Cork School of Dance) after Breda's death in 2009.[7] It is now run by Breda Quinn's family.

The Ballet Companies

The Cork Ballet Company (1947–1993)

Moriarty founded the Cork Ballet Group in 1947, the members recruited from her school. It gave its first performance in June of that year in the Cork Opera House, accompanied by the Cork Symphony Orchestra under its conductor Aloys Fleischmann. Stage scenery was designed by Marshall Hutson, Frank Sanquest and later by Patrick Murray; costume designs were provided by Clare Hutson, Maeve Coakley, Rachel Russell, who also made many of the costumes. Alec Day and Leslie Horne took charge of the lighting. From 1948 the group gave an annual week of ballet, also bringing its show to towns in Munster. In 1951 part of the classical ballet Coppélia was performed (the complete work in 1955), Giselle in 1957. In 1954 the group was registered as a company under the name "Cork Ballet Company". Its patrons were Marie Rambert, Alicia Markova and later Ninette de Valois. For the first ten years, Moriarty danced in many of the ballets. From 1956 the Company performed with international guest artists – among them, at a special ballet recital of 1965, Anton Dolin. From 1970 to 1973 it had very successful appearances in Dublin, in 1971–1973 performing with the Cork Symphony Orchestra for a week at the Gaiety Theatre to packed houses. In 1992 the Ballet Week was given in tribute to its founder, who had died in January of that year; the President of Ireland, Mary Robinson, attended the opening. The following year saw the last of the company's 46 seasons.[8]

The Folk Dance Group of the Cork Ballet Company

Moriarty founded this group in 1957. It participated in the Cork An Tóstal Festival for many years, travelled in 1958 to the Youth Festival of Wewelsburg (near Paderborn, Germany) and in 1961 to the Dijon International Folk Dance Festival in France. As a prize-winner, it was invited back to Dijon in 1965. In 1966 the group travelled to Berlin and participated successfully in the Deidesheim and Dillenburg Folk Dance Festivals. In 1966 and 1967 the group, together with the Cork Ballet Company, was commissioned by RTÉ, the state broadcasting service, to give 13 television programmes of Irish dance called "An Damhsa" (the dance), choreographed by Moriarty, costumes by Clare Hutson.[9]

Irish Theatre Ballet (1959–1964)

Irish Theatre Ballet was Ireland's first professional ballet company. Founded by Moriarty in the summer of 1959, it gave its first performance in December 1959 in the presence of its patron, Marie Rambert. It was a small touring company of 10 to 12 dancers, which travelled all over Ireland, north and south, going to some 70 venues annually with extracts from the classical ballets, contemporary works and folk ballets. Its first ballet master was Stanley Judson of the Anna Pavlova Company; then came Yannis Metsis of Ballet Rambert, then Denis Carey of Guatemalan State Ballet and finally Geoffrey Davidson of Festival Ballet. Charles Lynch was the company's pianist. Marshall Hutson and his wife Clare produced stage designs and costumes for many of the shows. 24 new ballets were created for the company; new music was commissioned for five of these, among them two folk ballets for which Seán Ó Riada provided scenarios and music, the latter performed by his Ceoltóirí Chualann. Irish Theatre Ballet received a small grant from the Arts Council of Ireland, aid from the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, but depended mainly on funding from business and private patrons. In an attempt to resolve the constant financial difficulties, the Arts Council in 1963 insisted on a merger with Patricia Ryan's Dublin National Ballet. But the amalgamation did not bring a solution to the financial problems besetting both companies, and after one joint season in Dublin in the late autumn of 1963 and in Cork the following January, the amalgamated company, Irish National Ballet, had to be disbanded in March 1964.[10]

Irish Ballet Company/Irish National Ballet (1973–1989)

In 1973, the Irish government decided to fund a professional ballet company for Moriarty: the Irish Ballet Company. It received a government grant at first and was subsequently financed by the Arts Council. Ninette de Valois was patron. She attended the first performance unannounced and donated half the Dutch Erasmus Prize, which she had just received, so that Moriarty could bring in distinguished teachers for special courses. Like Irish Theatre Ballet, Moriarty's first professional company, it was a touring company, which travelled all over Ireland in two annual seasons. David Gordon of the Royal Ballet was ballet master, Muriel Large administrator. Conditions were difficult for the dancers: salaries were small, as was the grant with which the company had to make do; the buildings that had to be used for training and rehearsal were far from ideal; performance facilities in the provincial centres were often dire. On the other hand, the dancers performed in a greater variety of roles than they would have done in a bigger company; they worked closely with many international choreographers and were encouraged to choreograph themselves. In 1975, for instance, Anton Dolin, Toni Beck and John Gilpin came to Cork to produce some of their works with the company. The Israeli choreographer, Domy Reiter-Soffer, who had been a member of Irish Theatre Ballet, became the company's artistic advisor and created many new works of great range in theme and type. Hans Brenaa, Nils Christe, Charles Czarny, Peter Darrell, Brenda Last, Michel de Lutry, Royston Maldoom were among the choreographers commissioned.

The company had a number of striking successes between 1978 and 1981. Moriarty's ballet based on J. M. Synge's play The Playboy of the Western World, commissioned for the Dublin Theatre Festival of 1978, with music played live by The Chieftains, was acclaimed. It went from Dublin to Cork to Belfast, to New York, to Sadler's Wells Theatre in London, and to Rennes in France. In 1981, the Dublin Theatre Festival commissioned Moriarty again; she created a 3-act ballet based on the old Irish epic The Táin; Fleischmann composed the music, Patrick Murray designed the sets. On the strength of these achievements, the government agreed in 1983 to the company changing its name to Irish National Ballet.[11]

The 1980s was a period of severe recession in Ireland. The Arts Council's budget was reduced amid increasing demands for the shrinking funds. In 1982 the Council ceased funding the Gate Theatre, the Dublin Theatre Festival and the Irish Theatre Company, the country's touring theatre company, continuing to support only the iconic Abbey Theatre.[12] The Council allotted a mere 7.6% of its budget to dance, and a large portion of that went to Irish National Ballet, though the grant was not substantial enough to keep the company out of debt. Contemporary dance groups and other dance organisations sought change in the distribution of the funds. In 1985 the Council commissioned the distinguished dance expert Peter Brinson to report on dance in Ireland. The report proposed a sharp reduction of the already inadequate budget of Irish National Ballet, while requiring it to incur greater expense through increased touring and to procure the funds needed from corporate sources.[13] It was critical of Moriarty, who resigned in the autumn of 1985. She was succeeded by the Finnish dancer and choreographer, Anneli Vourenjuuri-Robinson, who sought to implement a three-year plan accepted by the Arts Council. But in 1988 the Council decided to withdraw its grant before the end of the three-year period, and also terminated funding for Dublin Contemporary Dance Theatre. The Office of the Taoiseach thereupon gave Irish National Ballet a special grant for a year. Domy Reiter-Soffer and Patrick Murray directed the company during that time. The Arts Council did not reconsider its decision. The company's last ballet was Reiter-Soffer's Oscar based on the life of Oscar Wilde, set to music by Arnold Bax. It was performed in Dublin, Cork and Belfast. In 1989 Irish National Ballet had to be disbanded.[14]

A Home for National Irish Ballet

From 1973, appropriate accommodation was needed for the professional ballet company, which was operating in unsuitable premises. The Firkin Crane, the former centre of Cork's international butter trade, was put up for sale in 1979. Moriarty applied successfully to the Arts Council to have it bought for the Irish Ballet Company. A Trust Fund was set up to secure the finance for the rebuilding with former Taoiseach Jack Lynch as president. Cork City Council supported the undertaking; funding was also obtained from the Irish government, the European Union, Irish businesses and the American Ireland Fund. Planning started in 1982, building in 1985. When Irish National Ballet closed in 1989, the Firkin Crane was designated to become the Dance Centre of the city. It opened in April 1992, three months after Moriarty's death.

Artistic Achievement

Towards a new ballet style

Moriarty had a double dance training: she trained in ballet and in traditional Irish dance. This, together with her musical competence, provided a sound basis on which to develop a new type of ballet. She based many of her ballets on Irish mythology, legend and folklore. In this regard she was following in the footsteps of the writers of the previous generation, who had brought elements of speech deriving from the Irish language into their literary works and had drawn on the Gaelic literary heritage for their material. Aloys Fleischmann had a similar aim with regard to music. Both he and Moriarty sought to create a specifically Irish form of their respective arts with works on Irish themes, fusing elements of the Irish traditional heritage with the classical forms.[15] In the early years such a mingling of the dance forms was frowned upon by many traditional dancers – it must be remembered that this was fifty years before the Riverdance phenomenon.

The music for the dance

Moriarty commissioned new music for many of her Irish ballets. Elizabeth Maconchy, Seán Ó Riada and A. J. Potter orchestrated works originally written for the piano: Puck Fair (1948), Papillons (1952), and Full Moon for the Bride (1974). Redmond Friel composed the music for The Children of Lír (1950). Three ballets were set to Seán Ó Riada's music: West Cork Ballad (1961), Devil to Pay (1962), Lugh of the Golden Arm (1977); these were performed by the Ceoltóirí Chualann and Éamon de Buitléar's Ceoltóirí Laighean. The Chieftains arranged traditional music for The Playboy of the Western World. Bernard Geary wrote the music for two ballets choreographed by Geoffrey Davidson for Irish Theatre Ballet: Bitter Aloes and Il Cassone. Aloys Fleischmann composed the music for six Moriarty ballets: The Golden Bell of Ko (1948), An Cóitín Dearg [The Red Petticoat] (1951), Macha Ruadh [Red Macha] (1955), the two folk ballets Bata na bPlanndála [The Planting Stick] (1957) and Suite: The Cake Dance (1957) and The Táin (1981). This three-act ballet was commissioned by the Dublin Theatre Festival and premiered at the Gaiety Theatre, Dublin, on 6 October 1981, the Irish Ballet Company performing with the RTÉ Concert Orchestra under Proinnsias Ó Duinn.

The last composer to write for Moriarty was John Buckley: for her ballet Diúltú [Renunciation], based on a poem by Padraic Pearse. This was commissioned by the Department of the Taoiseach, the prime minister, in 1979, the year marking the centenary of Pearse's birth. It was premiered in June 1983 in Dublin's Abbey Theatre with Irish National Ballet accompanied by the RTÉ Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Colman Pearce. The ballet was performed again the following year.[16]

Moriarty spent almost 60 years working for ballet in Ireland. Her amateur Cork Ballet Company is still the longest-lasting ballet company the country has had; her two professional touring companies brought ballet to all parts of Ireland for in all 21 years. She received numerous awards for her work, among them an honorary doctorate from the National University of Ireland in 1979.[17]

Death

During the last years of her life, she suffered ill-health, but continued her work with the Cork Ballet Company, bringing the shows to towns in the county. She died on 24 January 1992 in Dublin.[18]

Moriarty Remembered

- Nov. 1992, Cork Opera House: Cork Ballet Company Giselle tribute performance, attended by President Robinson

- 1993, Firkin Crane, Cork: Sculpture of Moriarty unveiled

- 1997, Firkin Crane: Fiftieth anniversary of the founding of Cork Ballet Company; commemorative exhibition curated by Monica Gavin and Breda Quinn

- 2007, Cork City Library: Moriarty exhibition, curated by Monica Gavin, Breda Quinn, Cherry O'Keefe

- 2007, Bishopstown Library, Cork: Moriarty exhibition, curated by Monica Gavin, Breda Quinn, Cherry O’Keefe

- 25 April 2010, Siamsa Tíre, Tralee, County Kerry: Moriarty's ballet Bata na bPlanndála (The Planting Stick) choreographed by Pat Ahern, the founder of Siamsa Tíre (National Folk Theatre of Ireland) for his Fleischmann Centenary Concert, performed by Rinceoirí na Riochta with Jimmy Smith, Kerry Fleischmann Choir, Kerry Chamber Orchestra, conducted by Aidan O'Carroll.

- 26 April 2010, Firkin Crane: Cork City Ballet Fleischmann Centenary Gala with a revival of part of the Moriarty ballet The Golden Bell of Ko by Yuri Demakov. Opening of the exhibition "The Music for the Ballet" by Domy Reiter-Soffer

- 1 May 2010, Cork City Hall: Cork International Choral Festival closing concert, Moriarty's ballet Bata na bPlanndála (The Planting Stick) choreographed by Pat Ahern, performed by Rinceoirí na Riochta with Jimmy Smith, Kerry Fleischmann Choir, Kerry Chamber Orchestra conducted by Aidan O'Carroll

- 17–19 November 2011, Cork Opera House: Cork City Ballet, Giselle dedicated to Moriarty's memory

- 2012: Moriarty centenary celebrations under the auspices of Cork City Council, Cork City Ballet, The Firkin Crane, Cork City Libraries.[19]

Notes

- ↑ Aideen Rynne: "Joan Moriarty's Early Years", in: Ruth Fleischmann (Ed.): Joan Denise Moriarty: Founder of Irish National Ballet, Mercier Press, Cork 1998, pp. 118–119.

- ↑ Aideen Rynne: "Joan Moriarty's Early Years", in: Ruth Fleischmann (Ed.): Joan Denise Moriarty: Founder of Irish National Ballet, Mercier Press, Cork 1998, pp. 117–121.

- ↑ Ruth Fleischmann (Ed.): Joan Denise Moriarty, Ireland's First Lady of Dance, Cork, 2012, p. 75. Certificates, medals, newspaper cuttings in her personal scrapbook are among the Moriarty Collection, Cork City Central Library, Grand Parade, Cork.

- ↑ Aideen Rynne: 'Joan Moriarty's Early Years', in: Ruth Fleischmann (Ed.): Joan Denise Moriarty, Founder of Irish National Ballet, Cork 1998, pp. 118-119.

- ↑ Aideen Rynne: 'Joan Moriarty's Early Years', in: Ruth Fleischmann (Ed.): Joan Denise Moriarty, Founder of Irish National Ballet, Cork 1998, pp. 118-119.

- ↑ Aloys Fleischmann: "The Ballet in Cork", in: Ruth Fleischmann (Ed.): Joan Denise Moriarty, Founder of Irish National Ballet, Cork 1998 p. 15.

- ↑ Breda Quinn: "The Schools of Ballet", in: Ruth Fleischmann (ed.): Joan Denise Moriarty, pp. 87–88.

- ↑ See Monica Gavin, "The Cork Ballet Company: A Brief History ", in: Ruth Fleischmann (ed.): Joan Denise Moriarty: Ireland's First Lady of Dance, Cork 2012, p. 25.

- ↑ Monica Gavin: "The Folk Dance Group", in: Ruth Fleischmann (ed.): Joan Denise Moriarty, Founder of Irish National Ballet, Cork 1998, pp. 82–84.

- ↑ Geoffrey Davidson: "Irish Theatre Ballet", in: Ruth Fleischmann (ed.): Joan Denise Moriarty, Founder of Irish National Ballet, Cork 1998, pp. 157–158; see also there accounts by dancers Julia Cotter, Pat Dillon, Joahne O'Hara, Domy Reiter-Soffer, Maureen Weldon, pp. 158–175.

- ↑ See Catherine McMahon, Joan Denise Moriarty, Founder of Irish National Ballet, ed. Ruth Fleischmann, Cork 1998, p. 198

- ↑ Brian P. Kennedy: Dreams and Responsibilities: The State and the Arts in Independent Ireland, Dublin n.d. (1988), p. 264.

- ↑ Peter Brinson: The Dancer and the Dance, Dublin 1985, p. 24-28.

- ↑ Ruth Fleischmann: "The Arts Council and Irish National Ballet 1985–89", in: Joan Denise Moriarty, pp. 34–56.

- ↑ Séamas de Barra: Aloys Fleischmann, Dublin 2006, chapter 5: "The Idea of a Gaelic Art Music", pp. 45-72.

- ↑ Séamas de Barra: Aloys Fleischmann's Ballet Music, in: Ruth Fleischmann (ed.): Joan Denise Moriarty, Founder of Irish National Ballet, Cork 1998 pp. 104–113.

- ↑ See List of Honorary Degrees, nui.ie; accessed 28 April 2015.

- ↑ See Declan Hassett, "Tribute to the First Lady of Dance", Cork Examiner, 1.2.1992 p.11; Carolyn Swift, "End of an Era", Dance News Ireland, Spring 1992, p. 12.

- ↑ Ruth Fleischmann (Ed.) Joan Denise Moriarty, Ireland's First Lady of Dance, Cork 2012, pp. 70-71.

Literature

- Ruth Fleischmann (ed.): Joan Denise Moriarty: Founder of Irish National Ballet – Material for a History of Dance in Ireland (Cork: Mercier Press, 1998), ISBN 185635-234-X

- Brian P. Kennedy: Dreams and Responsibilities: The State and the Arts in Independent Ireland (Dublin: Arts Council of Ireland, n.d. [1988]), ISBN 0-906627-32-X

- Peter Brinson: The Dancer and the Dance (Dublin: Arts Council of Ireland, 1985), ISBN 0-906627-10-9

- Séamas de Barra: Aloys Fleischmann (Dublin: Field Day Publications, 2006), ISBN 978-0-946755-32-5

- Patrick Zuk: A.J. Potter (1918–1980): The Career and Creative Achievement of an Irish Composer in Social and Cultural Context (unpublished Ph.D. thesis, Durham University, 2008)

- Victoria O'Brien: A History of Irish Ballet from 1927 to 1963 (Bern et al: Peter Lang, 2011), ISBN 978-3-03911-873-1

- Ruth Fleischmann (ed.): Joan Denise Moriarty: Ireland's First Lady of Dance (Cork: Cork City Libraries, 2012), ISBN 978-0-9549847-8-6

External links

- Cork City Libraries: Joan Denise Moriarty

- Cork Ballet Company Programmes

- The Firkin Crane Centenary Gala

- Joan Denise Moriarty Facebook

- Joan Denise Moriarty: Ireland's First Lady of Dance, Ed. Ruth Fleischmann, Cork 2012

- Claire Dix 2016 Moriarty documentary trailer