John Harvard (clergyman)

| John Harvard | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

26 November 1607 Southwark, England |

| Died |

14 September 1638 (aged 30) Charlestown, Massachusetts Bay Colony |

| Cause of death | Tuberculosis |

| Alma mater | Emmanuel College (University of Cambridge) |

| Occupation | Pastor |

| Known for | A founder of Harvard College |

| Spouse(s) | Ann Sadler |

| Children | None |

| Signature | |

|

| |

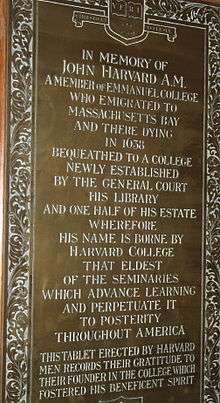

John Harvard (26 November 1607 – 14 September 1638) was an English minister in America, "a godly gentleman and a lover of learning",[1] whose deathbed[2] bequest to the "schoale or Colledge" recently undertaken by the Massachusetts Bay Colony was so gratefully received that it was consequently ordered "that the Colledge agreed upon formerly to bee built at Cambridg shalbee called Harvard Colledge." [3] Despite a persistent myth to the contrary, John Harvard is properly considered one of the founders of Harvard College.

A statue in his honor is a prominent feature of Harvard Yard.

Life

Early life

Harvard was born and raised in Southwark, England, the fourth of nine children of Robert Harvard (1562–1625), a butcher and tavern owner, and his wife Katherine Rogers (1584–1635), a native of Stratford-upon-Avon whose father, Thomas Rogers (1540–1611), was an associate of Shakespeare's father, both serving on the borough corporation's council. He was baptised in the parish church of St Saviour's (now Southwark Cathedral)[4] and attended St Saviour's Grammar School, where his father was a member of the governing body as being also a Warden of the Parish Church.

In 1625, the plague reduced the immediate family to only John, his brother Thomas, and their mother. Katherine was soon remarried—

Left with some property, Harvard's mother was able to send him to Emmanuel College, Cambridge,[5] where he earned his B.A. in 1632[6] and M.A. in 1635.[7]

Marriage and career

In 1636, he married Ann Sadler (1614–55) of Ringmer, sister of his college classmate John Sadler, at St Michael the Archangel Church, in the parish of South Malling, Lewes, East Sussex.

In the spring or summer of 1637, the couple emigrated to New England, where Harvard became a freeman of Massachusetts and,[5] settling in Charlestown, a teaching elder of the First Church there[8] and an assistant preacher.[7] In 1638, a tract of land was deeded to him there, and he was appointed that same year to a committee "to consider of some things tending toward a body of laws."[5]

He built his house on Country Road (later Market and now Main Street) next to Gravel Lane, a site that is now Harvard Mall. Harvard's orchard extended up the hill behind his house.[9]

Death

On 14 September 1638, he died of tuberculosis and was buried at Charlestown's Phipps Street Burying Ground. In 1828, Harvard University alumni erected a granite monument to his memory there,[5][10] his original stone having disappeared during the American Revolution.[8]

Founder of Harvard College

Two years before Harvard's death the Great and General Court of the Massachusetts Bay Colony—

Founding "myth"

"Smartass" tourguides[17][18]

and the Harvard College undergraduate newspaper[19]

commonly assert that John Harvard does not merit the honorific founder, because the Colony's vote had come two years prior to Harvard's bequest.

But as detailed in a 1934 letter by the secretary of the Harvard Corporation, the founding of Harvard College was not the act of one but the work of many; John Harvard is therefore considered not the founder, but rather a founder,[20][21] of the school—

The quibble over the question whether John Harvard was entitled to be called the Founder of Harvard College seems to me one of the least profitable. The destruction of myths is a legitimate sport, but its only justification is the establishment of truth in place of error.

If the founding of a university must be dated to a split second of time, then the founding of Harvard should perhaps be fixed by the fall of the president's gavel in announcing the passage of the vote of October 28, 1636. But if the founding is to be regarded as a process rather than as a single event [then John Harvard, by virtue of his bequest "at the very threshold of the College's existence and going further than any other contribution made up to that time to ensure its permanence"] is clearly entitled to be considered a founder. The General Court ... acknowledged the fact by bestowing his name on the College. This was almost two years before the first President took office and four years before the first students were graduated.

These are all familiar facts and it is well that they should be understood by the sons of Harvard. There is no myth to be destroyed.[22]

Memorials and tributes

A statue in Harvard's honor—not, however, a likeness of him, there being nothing to indicate what he had looked like[7]—is a prominent feature of Harvard Yard (see John Harvard statue) and was featured on a 1986 stamp, part of the United States Postal Service's Great Americans series.[23] A figure representing him also appears in a stained-glass window in the chapel of Emmanuel College, University of Cambridge.[7][5]

The John Harvard Library in Southwark, London, is named in Harvard's honor, as is the Harvard Bridge that connects Boston to Cambridge.[24]

References

- ↑ Samuel Eliot Morison, The founding of Harvard College (1936) Appendix D, and pp 304-5

- ↑ Conrad Edick Wright, John Harvard: Brief life of a Puritan philanthropist Harvard Magazine. January–February, 2000. "By the time the Harvards settled in Charlestown John must already have been in failing health ... Consumption kills slowly. By the time Harvard died, he knew what he wanted to do with his estate."

- 1 2 3 4 Charter of the President and Fellows of Harvard College

- 1 2 Rowston, Guy (2006). Southwark Cathedral – The authorised Guide.

- 1 2 3 4 5

Wilson, James Grant; Fiske, John, eds. (1892). "Harvard, John". Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton.

Wilson, James Grant; Fiske, John, eds. (1892). "Harvard, John". Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton. - ↑ "Harvard, John (HRVT627J)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- 1 2 3 4 Emmanuel College: John Harvard Retrieved 2012-05-01 and was subsequently ordained a dissenting minister.

- 1 2 Melnick, Arseny James. "Celebrating the Life and Times of JOHN HARVARD". Retrieved 20 September 2011.

- ↑ Charlestown Historical Society: Full Historic Timeline

- ↑ Edward Everett (1850). Orations and speeches on various occasions. I. Boston: Charles C. Little and James Brown. pp. 185–189.

- ↑ New England's First Fruits (1643). https://books.google.com/books?id=gXkFAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA16

- ↑ Callan, Richard L. 100 Dears of Solitude: John Harvard Finishes His First Century. The Harvard Crimson. 28 April 1984. Retrieved 13 October 2012

- ↑ The Harvard Graduates' Magazine. 16. Harvard Graduates' Magazine Association. 1908. Retrieved 2014-05-12.

- ↑ Alfred C. Potter, "The College Library." Harvard Illustrated Magazine, vol. IV no. 6, March 1903, pp. 105–112.

- ↑ Potter, Alfred Claghorn (1913). Catalogue of John Harvard's library. Cambridge: J. Wilson.

- ↑ Degler, Carl Neumann (1984). Out of Our Pasts: The Forces That Shaped Modern America. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-131985-3. Retrieved 20 September 2011.

- ↑ Shand-Tucci, Douglas (2001). The Campus Guide: Harvard University. Princeton Architectural Press. pp. 46–51. ISBN 9781568982809.

- ↑ Primus V (May–June 1999). "The College Pump. Toes Imperiled". Harvard Magazine.

- ↑ "Memorial Society Honors Founder of College In the Name and Image of Two Other Men – College Founded By Grant of the Massachusetts General Court in the Year 1636". Harvard Crimson. 26 November 1934.

When the members of the Memorial Society place a wreath on the statue of John Harvard today, expecting to honor the memory and the image of the founder of Harvard College, they will be honoring the likeness of another man and the name of a man who was not the legal founder of the college.

- ↑ Morison, Samuel Eliot (1935). The Founding of Harvard College. p. 210.

John Harvard cannot rightly be called the founder of Harvard College...

- ↑ Mather, Cotton (1853). Robbins, Thomas, ed. Magnalia Christi Americana: Or, The Ecclesiastical History of New-England, from Its First Planting, in the Year 1620, Unto the Year of Our Lord 1698 ... 2. Hartford: S. Andrus & Son. p. 10.

But that which laid the most significant stone in the foundation, was the last will of Mr. John Harvard ...

- ↑ Excerpted from Greene, Jerome Davis (11 December 1934). "Don't Quibble Sybil — The Mail" (Letter to the editor)". Harvard Crimson. ("Don't quibble, Sybil" is a line from Noël Coward's 1930 Private Lives.)

- ↑ usstampgallery.com: John Harvard

- ↑ Alger, Alpheus B.; Matthews, Nathan Jr. (1892). Harvard Bridge: Boston to Cambridge, March 1892. Boston, Massachusetts: Rockwell and Churchill. p. 14. Retrieved 20 September 2011.

Further reading

- Shelley, Henry C. (1907). John Harvard and His Times. Boston, Mass.: Little, Brown, and Co.

- Rendle, William (1885). John Harvard, St. Saviour's, Southwark, and Harvard University, U.S.A. London: J.C. Francis.

External links

| Wikisource has the text of an 1879 American Cyclopædia article about John Harvard. |

| Wikisource has the text of a 1905 New International Encyclopedia article about John Harvard. |

- Harvard House The home of Katherine Rogers in Stratford-Upon-Avon

- Potter, Alfred Claghorn (1913). Catalogue of John Harvard's library. Cambridge: J. Wilson.