John Henry Towers

| John Henry Towers | |

|---|---|

Towers in 1943 | |

| Born |

January 30, 1885 Rome, Georgia, U.S. |

| Died |

April 30, 1955 (aged 70) Jamaica, New York, U.S. |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/branch |

|

| Years of service | 1908–1947 |

| Rank |

|

| Commands held |

Pacific Fleet 5th Fleet 2d Carrier Task Force and Task Force 38 USS Langley (CV-1) USS Mugford (DD-105) USS Saratoga (CV-3) |

| Battles/wars |

World War I World War II |

| Awards |

Navy Cross Navy Distinguished Service Medal Legion of Merit NC-4 Medal |

| Relations | Herbert D. Riley (son-in-law) |

| Other work |

President, Pacific War Memorial President, Flight Safety Council |

John Henry Towers (January 30, 1885 – April 30, 1955) was a United States Navy admiral and pioneer naval aviator. He made important contributions to the technical and organizational development of naval aviation from its very beginnings, eventually serving as Chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics (1939–1942). He commanded carrier task forces during World War II, and retired in December 1947. He and Marc Mitscher were the only early Naval Aviation pioneers to survive the extreme hazards of early flight to remain with naval aviation throughout their careers. He was the first naval aviator to achieve flag rank and was the most senior advocate for naval aviation during a time when the Navy was dominated by battleship admirals. Towers spent his last years supporting aeronautical research and advising the aviation industry.

Early life and career

Towers was born on 30 January 1885 at Rome, Georgia. He graduated from the United States Naval Academy in the Class of 1906, and was commissioned ensign in 1908 while serving aboard the battleship USS Kentucky (BB-6). He was later assigned to the battleship USS Michigan (BB-27) before reporting to the Curtiss Flying School in Hammondsport, New York, on June 27, 1911 for aviation training.[1]

Pioneer naval aviator

Under the tutelage of aviation pioneer Glenn Curtiss and Lieutenant Theodore G. Ellyson, Towers qualified as a pilot in August 1911, flying the Navy's first airplane, a Curtiss A-1 seaplane.

Towers next traveled to North Island in San Diego, California where, in conjunction with the Curtiss Flying School, he took part in developing and improving naval aircraft types [2]

In October 1911, Towers achieved a distance record, flying an A-1 from Annapolis, Maryland, to Old Point Comfort, Virginia, a distance of 112 miles in 122 minutes. In the fall of 1912, Towers supervised the establishment of the Navy's first aviation unit, based at Annapolis. On October 6, 1912, he achieved an American endurance record by rigging extra gasoline tanks to a Curtiss A-2 seaplane, allowing him to remain aloft for 6 hours, ten minutes, 35 seconds. From October to December 1912, Towers conducted tests to spot submerged submarines from the air over the Chesapeake Bay. He furthered those tests into 1913 during fleet operations near Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. Additionally, he investigated the potential for Navy aerial reconnaissance, bombing, photography, and communications.[1]

On 8 May 1913, Lt. Towers flew a long-distance flight of 169 miles in a Curtiss flying boat from the Washington Navy Yard down the Potomac River and then up the Chesapeake Bay to the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis, Maryland. The flight took three hours and five minutes. Ensign Godfrey Chevalier was his passenger.[3]

On 20 June 1913, Towers was nearly killed in an aviation mishap over the Chesapeake Bay. While he was flying as a passenger in a Wright seaplane, his plane was caught in a sudden downdraft and plummeted earthward. The pilot, Ensign W.D. Billingsley, was thrown from the aircraft and killed (becoming the first naval aviation fatality). Towers also was wrenched from his seat but managed to catch a wing strut and stay with the plane until it crashed into the Chesapeake. Interviewed by Glenn Curtiss soon thereafter, Towers recounted the circumstances of the tragedy; his report and resultant recommendations eventually led to the design and adoption of safety belts and harnesses for pilots and their passengers.

On 20 January 1914, Lieutenant Towers led 9 officers and 23 enlisted men, with 7 aircraft, portable hangars and other gear from the aviation unit at Annapolis to Pensacola, Fla to set up the first naval aviation training unit. Then on April 20, 1914, Towers led the first naval aviation unit called into action with the Fleet. He and two other pilots, 12 enlisted men and three aircraft sailed from Pensacola aboard the cruiser Birmingham in response to the Tampico Affair[4]

Naval aviator designation and insignia

In January 1915, the Navy decided to officially designate its flyers. At that time, Towers was officially designated as Naval Aviator No. 3, with an effective date of 1914.[5] Lieutenant Commander Towers, while assigned to the aviation desk under CNO, is credited with the development of the Naval Aviators badge, which were designed and ordered in 1917.[6] On January 19, 1918, distribution of the first gold Naval Aviator wings began, and it is likely that Towers, as Senior Naval Aviator in Washington at the time, was an early, if not the earliest, recipient.[6]

World War I

In August 1914, shortly after the war began, Towers was ordered to London as assistant naval attaché—a billet he filled until he returned to the United States in the autumn of 1916. That August Lieutenant Towers accompanied the U.S. Relief Expedition aboard the USS Tennessee as part of the naval delegation led by Commander Reginald R. Belknap, with overall command by Assistant Secretary of the Army Henry S. Breckinridge. Subsequently, Towers advocated for the First Yale Unit, which would become the core of naval aviation's participation in the war.

In May 1917, Lieutenant Commander Towers was ordered to the Bureau of Navigation as Supervisor of the Naval Reserve Flying Corps, a precursor to the Naval Air Reserve Force. When the Navy established the Division of Aviation, at Navy Department headquarters, Towers was appointed Assistant Director of Naval Aviation. In that position, he orchestrated the buildup from a handful of obsolete aircraft and fewer than 50 pilots to a force of thousands of aircraft and aviators.

Interwar years, 1919–1939

During the interwar years, Towers was the leading advocate of Naval Aviation (and especially carrier aviation) when there was virtually no other support within or outside of the navy. He was involved in a number of pioneering developments in Naval Aviation, including the first transatlantic crossing by aircraft; serving as commander of the first U.S. aircraft carrier, USS Langley (CV-1); and holding important positions (including bureau chief) within the Bureau of Aeronautics (BuAer), the organizational structure established for Naval Aviation in 1921.

Transatlantic crossing: Flight of NC-4, 1919

In 1919, then-Commander Towers proposed, planned and led the first air crossing of the Atlantic.[7] Planning for the mission actually began during the early years of World War I, when Allied shipping was threatened by submarine warfare, but could not be accomplished prior to the war's end. The flying expedition began on 8 May 1919 when three Curtiss NC Flying Boats, designated NC-1, NC-3 and NC-4, left Naval Air Station Rockaway, New York,[8] The aircraft made intermediate stops in Chatham, Massachusetts and Halifax, Nova Scotia before reaching Trepassey, Newfoundland on 15 May 1919.

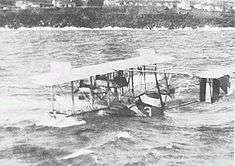

On 16 May they left for the longest leg of their journey, to the Azores. NC-1 and the NC-3 were both forced to land in heavy seas due to dense fog, and neither could take off again. NC-1 subsequently began taking on water and the crew was rescued by the Greek freighter Ionia.[9] The crew of the NC-3, including Towers, managed to keep the NC-3 afloat for 52 hours, water taxiing the craft over 200 miles to Punta Delgada on Sao Miguel Island. NC-4 went on to complete the transatlantic crossing, arriving at Lisbon on 27 May. For his leadership in the operation, Towers was awarded the Navy Cross. Ten years later, Towers and the flight crew of NC-4 were awarded Congressional Gold Medals.[10]

Sea and shore assignments, 1920s and 1930s

Between the autumn of 1919 and the late winter of 1922 and 1923, Towers served at sea—as the executive officer of USS Aroostook and as the commanding officer of the old destroyer USS Mugford, which had been redesignated an aircraft tender. Then, after a tour as executive officer at NAS Pensacola, he spent two and one-half years—from March 1923 to September 1925—as an assistant naval attaché, serving at the American embassies at London, Paris, Rome, the Hague, and Berlin.

Returning to the United States in the autumn of 1925, he was assigned to the Bureau of Aeronautics and served as a member of the court of inquiry which investigated the loss of dirigible USS Shenandoah.

Towers next commanded USS Langley, the Navy's first aircraft carrier, from January 1927 to August 1928. He received a commendation for "coolness and courage in the face of danger" when a gasoline line caught fire and burned on board the carrier in December 1927. Towers personally led the vigorous and successful effort to suppress the flames kindled by the explosion and thus averted a catastrophe.

After shore duty in the Bureau of Aeronautics, Towers successively served as head of the plans division and later, as assistant bureau chief. Towers joined the staff of the Commander, Aircraft, Battle Force, under Rear Admiral Harry E. Yarnell, in June 1931. He was among the staff which planned a successful "attack" on Pearl Harbor during the Joint Army-Navy Exercise No. 4 in the Hawaiian Islands in February 1932—an operation which was to be duplicated on a larger scale by the Japanese in December 1941.

Between June 1933 and June 1939, Towers filled a variety of billets ashore and afloat: he completed the senior course at the Naval War College in 1934; commanded the Naval Air Station at San Diego; again served on the staff of ComAirBatFor; commanded USS Saratoga (CV-3); and became Assistant Chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics. On 1 June 1939, he was named Chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics with the accompanying rank of rear admiral.

World War II

As Aeronautics Bureau chief, Towers organized the Navy's aircraft procurement plans while war clouds gathered over the Far East and in the Atlantic. Under his leadership, the air arm of the Navy grew from 2,000 planes in 1939 to 39,000 in 1942. He also instituted a rigorous pilot-training program and established a trained group of reserve officers for ground support duties. During Towers' tenure, the number of men assigned to naval aviation activities reached a high point of some three quarters of a million.

World War II operational commands

Promoted to vice admiral on 6 October 1942, Towers became Commander, Air Force, Pacific Fleet. From this billet, he supervised the development, organization, training, and supply of the Fleet's growing aviation capability, and helped develop the strategy which spelled the doom of the Japanese fleet and eventual American victory in the Pacific. For his "sound judgment and keen resourcefulness", Towers received, successively, the Legion of Merit and the Distinguished Service Medal. Towers was subsequently promoted to the dual position of Deputy Commander-in-Chief, Pacific Ocean Area (DCINCPOA) and Deputy Commander-in-Chief, Pacific Fleet (DCINCPAC). In this capacity, he served as Admiral Chester Nimitz's chief advisor on naval aviation policy, fleet logistics, and administration matters.

In August 1945, Towers was given command of the Second Carrier Task Force and Task Force 38, Pacific Fleet. On 7 November 1945, he broke his flag aboard the battleship USS New Jersey (BB-62) as Commander, 5th Fleet. On 1 February 1946, he made the carrier USS Bennington (CV-20) his flagship as Commander in Chief, Pacific Fleet, a post he held until March 1947.

In 1946, President Truman signed the first Outline Command Plan (now known as the Unified Command Plan) that called for the establishment of several joint or unified commands. On 1 January 1947, the new United States Pacific Command stood up as one of the first unified commands with Admiral Towers as its first commander. He served as the commander of Pacific Command for only two months before being reassigned: 1 January 1947 - 28 February 1947. Admiral Towers was dual-hatted as both Commander in Chief, Pacific Fleet and Commander in Chief, Pacific Command.

Post-war service and retirement

After chairing the Navy's General Board from March to December 1947, Towers retired on 1 December 1947. After retirement, Towers served as President of the Pacific War Memorial, as assistant to the President of Pan American World Airways, and as President of the Flight Safety Council. Admiral Towers died in St. Albans' Hospital, Jamaica, New York, on 30 April 1955 and was buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

Honors and awards

In 1961, Towers was posthumously designated the second recipient of the Gray Eagle Award, as the most senior active naval aviator from 1928 until his retirement. He was enshrined in the National Aviation Hall of Fame in 1966, the International Aerospace Hall of Fame in 1973, the Naval Aviation Hall of Honor in 1981 and the Georgia Aviation Hall of Fame in 2004.

The decorations and medals he earned during his career include the following -

Namesakes

USS Towers (DDG-9), a guided missile destroyer that saw action in the Vietnam War, was named in his honor. A crater on the moon was named in his honor by the Apollo 17 Mission [11] Towers Field at Jacksonville Naval Air Station in Jacksonville, Florida is named for him, as is the air field at Richard B. Russell Regional Airport, Rome, Georgia.[12] A pool located on the United States Pacific Fleet command section of Pearl Harbor is named after him.

See also

References

- ↑ "Towers, John Henry". www.history.navy.mil. Retrieved 2016-01-15.

- ↑ http://home.earthlink.net/~ralphcooper/pimage5.htm

- ↑ http://www.history.navy.mil/branches/ww1av.htm

- ↑ http://www.history.navy.mil/avh-1910/APP01.PDF

- 1 2 http://www.history.navy.mil/download/ww1-10.pdf

- ↑ http://www.history.navy.mil/branches/nc-4mono.htm

- ↑ Now de-commissioned and part of Gateway National Recreation Area

- ↑ Aviation History website

- ↑ Congressional Gold Medal awarded to the crew of the first transatlantic flight Towers was awarded along with the flight crew of NC-4

- ↑ Isakson, Johnny (May 20, 2009). Congressional Record. 155 (78) http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/CREC-2009-05-20/html/CREC-2009-05-20-pt1-PgS5694.htm. Retrieved 28 January 2012. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ http://romenews-tribune.com/view/full_story/5697870/article-Rome-native-Towers-featured-in-new-book?

- This article incorporates text from the public domain Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships.

- Reynolds, Clark G. Admiral John H. Towers: The Struggle for Naval Air Supremacy. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1991.

External links

- Biographical information on Admiral Towers and ship history for USS Towers (DDG-9) from the Naval Historical Center

- John H. Towers Papers (Library of Congress)

- Text of Georgia Senate Resolution SR-942, honoring Admiral Towers The text includes a brief recital of Towers' Georgia roots and naval accomplishments. The resolution was to approve the placing of a portrait of Towers in the Georgia State Capitol.

| Military offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Raymond A. Spruance |

Commander in Chief of the United States Pacific Fleet 1946–1947 |

Succeeded by Louis E. Denfeld |

| Preceded by None |

Commander in Chief, United States Pacific Command 1946–1947 |

Succeeded by Louis E. Denfeld |