John Strugnell

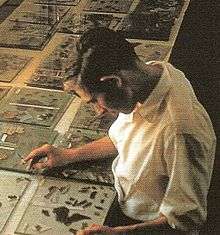

John Strugnell (May 25, 1930 – November 30, 2007) was born in Barnet, Hertfordshire, UK. At the age of 23 he became the youngest member of the team of scholars led by Roland de Vaux, formed in 1954 to edit the Dead Sea Scrolls in Jerusalem. He was studying Oriental languages at Jesus College, Oxford when Sir Godfrey Rolles Driver, a lecturer in Semitic philology, nominated him to join the Scrolls editorial team. Although Strugnell had no previous experience in palaeography he learned very quickly to read the scrolls. He would be involved in the Dead Sea Scrolls project for more than forty years.[1] John Strugnell died in Boston, Massachusetts, on November 30, 2007.

Early career

Strugnell was educated at St. Paul's School in London. He took a double first in Classics and Semitics at Oxford but never finished his dissertation and only held a master's degree. Despite not having completed his doctorate, Strugnell was given a position at the Oriental Institute of Chicago in 1956-1957, where he met his future wife, Cecile Pierlot, whose father had been Prime Minister of Belgium during the Second World War. He was away from his scrolls again from 1960 to 1967, this time at Duke University, though he returned in summers to continue his efforts in Jerusalem. Still without his doctorate, as he would be for the rest of his life, Strugnell served from 1966-1991 as Professor of Christian Origins at Harvard.[2] He succeeded Pierre Benoit as editor-in-chief of the scrolls in 1984, a position he held until 1990. During this period he was responsible for bringing Elisha Qimron and Emanuel Tov to work on the scrolls, breaking the longstanding exclusion of Israeli scholars.[1] At the same time, he kept notable scholars such as Theodor Gaster and Robert Eisenman from having access to the scrolls, a situation that was rectified when Strugnell was removed from his post and the scrolls (such as those at the Huntington Library in California) were opened to the wider scholarly community for the first time.[3][4]

Editor in Chief

His production of editions of texts was not large, but the texts which he did publish were all exceptionally important, including "The Angelic Liturgy", later published as Songs of the Sabbath Sacrifices (Shirot 'olat ha-Shabbat), and "An Unpublished halakhic Letter from Qumran", later known as MMT [or 4QMMT] from the Hebrew (Miqtsat Ma'asei ha-Torah), this latter text being edited with Elisha Qimron, who did much of the work. These texts helped to enrich scholarly knowledge of the cultus of the writers of the Dead Sea Scrolls. Nevertheless, he was a slow worker and the times had changed since it was acceptable to keep the scrolls protected from what was once considered misuse and hasty publication.

For many years, scholars had accepted the lack of access to unpublished texts and the slow publication of the texts. This changed during Strugnell's editorship, for there came a growing movement of scholars calling for access to the Scrolls. By this time his health had deteriorated. Only one volume was produced under his general editorship, The Greek Minor Prophets Scroll from Nahal Hever, by Emanuel Tov.

Ha'aretz interview controversy

In 1990, Strugnell gave an interview to Ha'aretz in which he said that Judaism was a "horrible religion" which "should not exist". He also said that Judaism was "a Christian heresy, and we deal with our heretics in different ways. You are a phenomenon that we haven't managed to convert — and we should have managed."[5]

There was immediate condemnation of his comments, including an editorial in the New York Times. As a result of the interview, Strugnell was forced to take early retirement on medical grounds at Harvard,[2] and he was finally removed from his editorial post on the scrolls project, the Antiquities Authority citing his deteriorating health as reason for his removal.[5]

Strugnell later said that he was suffering from stress-induced alcoholism and manic depression when he gave the interview. He insisted that his remarks were taken out of context, and he only meant "horrible" in the Miltonian sense of "deplored in antiquity". In a 2007 interview in Biblical Archaeology Review, Frank Moore Cross said that despite Strugnell's comments, which were based on a theological argument of the early Church Fathers that Christianity superseded Judaism, Strugnell had very friendly relationships with a number of Jewish scholars, some of whom signed a letter of support for him which was published in the Chicago Tribune, January 4, 1991, pg. N20.

Aftermath

Strugnell had come increasingly under controversy for his slow progress in publishing the scrolls, and his refusal to give scholars free access to the unpublished scrolls. Some argue the removal of Strugnell from his editorial post ended the more than three-decade blockade that he and other Harvard-educated scholars, such as Notre Dame's Eugene Ulrich, had maintained to keep other scholars from accessing the scrolls.[6] The blockade on the publication of the scrolls effected by Strugnell and other members of Harvard's academic community was broken by the combined efforts of Hershel Shanks of the Biblical Archaeology Review (who had personally waged a 15-year campaign to release the scrolls) and Ben Zion Wacholder of Hebrew Union College, along with his student, Martin Abegg, who published the first facsimile of the suppressed scrolls in 1991.[7] Strugnell insisted that he tried to publish the scrolls as quickly as he could but that his team was the limiting factor.

Shortly after Strugnell was dismissed from his post, he was institutionalized in McLean Hospital for a period. At the time of his death, he was Professor Emeritus at the Harvard Divinity School.

The Strugnell Library

In 2003, City Seminary of Sacramento acquired Strugnell's library of over 4,000 volumes, including texts on Hebrew, Aramaic, Syriac, Ethiopic — as well as works on Greek and Latin, and large sections on classical studies, Patristics (Early Church writings), apocryphal and pseudepigraphal (falsely attributed) literature, and books on Judaism, Christianity, Hebrew Bible and New Testament studies. A highlight of the collection is Strugnell’s personal copy of the Dead Sea Scrolls concordance. The early scrolls team made a concordance of the words in the unpublished texts to assist their own work.[8][9]

References

- 1 2 Sidnie White Crawford, "John Strugnell (1930–2007)" Obituary, Bible History Daily, Biblical Archaeology Society (11 December 2007). Retrieved 22-11-2013.

- 1 2 The Times obituary December 29, 2007

- ↑ John Noble Wilford, "John Strugnell, Scholar Undone by His Slur, Dies at 77," The New York Times (December 9 2007). Retrieved 22-11-2013.

- ↑ John Noble Wilford, "Open, Dead Sea Scrolls Stir Up New Disputes," The New York Times (April 19 1992). Retrieved 22-11-2013.

- 1 2 "Scrolls' Editor Is Formally Dismissed," The New York Times (January 1, 1991). Retrieved 22-11-2013.

- ↑ 'Copies Of Dead Sea Scrolls To Go Public -- Release Would End Scholars' Dispute' - The Seattle Times 22 September 1991

- ↑ James R. Adair, Jr, "Old and New in Textual Criticism: Similarities, Differences, and Prospects for Cooperation," A Journal of Biblical Textual Criticism (1996)]

- ↑ Strugnell Collection in the City Seminary of Sacramento Archived July 6, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Detroit Jewish News

- Article by John J. Collins on John Strugnell, in The Encyclopaedia of the Dead Sea Scrolls, ed. Lawrence Schiffman and James VanderKam, Oxford, 2000.

- The Meaning of the Dead Sea Scrolls, James VanderKam and Peter Flint, HarperSanFransisco, 2002.

- "Headliners: Fallen Scholar", New York Times, Week in Review, December 16, 1990

- Ron Rosenbaum, "The Riddle of the Scrolls", Vanity Fair, reprinted in The Secret Parts of Fortune

External links

- Harvard Divinity School bio

- Strugnell on the Biblical Archaeology Society website

- John Strugnell in the New York Times

- City Seminary of Sacramento acquires the Strugnell Library

- Detroit Jewish News, 12/1/2002, on sale of his library through Dove Books