Judicial aspects of race in the United States

Race legislation in the United States is defined as legislation seeking to direct relations between so-called "races" (a social construct) or ethnic groups. It has had several historical phases in the United States, developing from the European colonization of the Americas, the triangular slave trade, and the American Indian Wars. The 1776 Declaration of Independence included the statement that "all men are created equal," which has ultimately inspired actions and legislation against slavery and racial discrimination. Such actions have led to passage of the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments to the United States Constitution.

The first period extends until the Civil War and the Reconstruction era, the second spans the nadir of American race relations period through the early 20th century; the last period begins with World War II and the following increased civil rights movement, leading to the repeal of racial segregation laws. Race legislation has been intertwined with immigration laws, which sometimes included specific provisions against particular nationalities or ethnicities (i.e. Chinese Exclusion Act or 1923 United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind case).

Legislation until the American Civil War and Reconstruction

Until the Civil War, slavery was legal. After the Revolutionary War, the new Congress passed the Naturalization Act of 1790 to provide a way for foreigners to become citizens of the new country. It limited naturalization to aliens who were "free white persons" and thus left out indentured servants, slaves, free African-Americans, and later Asians. In addition, many states enforced anti-miscegenation laws (e.g. Indiana in 1845), which prohibited marriage between whites and non-whites, that is, blacks, mulattoes, and, in some states, also Native Americans. After an influx of Chinese immigrants to the West Coast, marriage between whites and Asians was banned in some western states.

After the Revolutionary War, most northern states abolished slavery, even if on a gradual emancipation plan. Congress enacted Fugitive slave laws in 1793 and 1850 to provide for the return of slaves who had escaped from a slave state to a free state or territory. Black Codes were adopted by several states, generally to constrain the actions and rights of free people of color, as slaves were controlled by slave law. Although most northern states had abolished slavery, several tried to discourage freedmen from settling in the state. In some states, the Black Codes were incorporated into, or required by, the state constitution, many of which were rewritten in the 1840s. For instance, Article 13 of Indiana's 1851 constitution stated "No Negro or Mulatto shall come into, or settle in, the State, after the adoption of this Constitution." The 1848 constitution of Illinois led to one of the harshest Black Code systems in the nation before the Civil War. The Illinois Black Code of 1853 extended a complete prohibition against black immigration into the state.

The Indian Removal Act of 1830 legalized deportation of Native Americans to the West; it was passed primarily to extinguish Native American tribal claims to territory in what became known as the Deep South. Under the act, the federal government removed the Five Civilized Tribes to Indian Territory. The Indian Intercourse Act of 1837 created the Indian Territory in present-day Kansas and Oklahoma as the areas where tribes would be resettled. While the tribes retained self-government and territory, their peoples were generally not considered United States citizens.

The largest federal establishment of reservations began with the Indian Appropriations Acts in the 1850s. The Dawes Act of 1887 registered members of the so-called "Five Civilized Tribes" and included privatization of common holdings of American Indians. Blood quantum laws determined membership in Native American groups. Some of its measures were repealed with the 1934 Indian Reorganization Act, allowing a return to local self-government. Citizenship was not granted to Native Americans until the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924, but by that time, two-thirds of Native Americans were already citizens because of other actions.

The Dred Scott case of 1857, a "freedom suit" which was appealed to the Supreme Court, was settled with the ruling that, as the Constitution had not included people of African descent, whether they were enslaved or free, they could not be citizens of the United States (and therefore never had standing to file freedom suits or other legal cases).

The victory of the North during the Civil War led to the abolition of slavery with the Thirteenth Amendment and an expansion of the civil rights of African-Americans with the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment. The Fourteenth Amendment also overturned The Fifteenth Amendment prohibited disenfranchisement on the basis of race. The Naturalization Act of 1870 ensured that immigrants people of African descent could become citizens by the naturalization process.

Legislation during the nadir of American race relations

Following the end of the Reconstruction period, southern whites reasserted political and social supremacy, with the violence and discrimination that caused the nadir of American race relations. There was increasing racial violence in the South, lynchings and attacks to intimidate blacks and repress their voting. After regaining power in the state legislatures in the 1870s, white Democrats passed legislation to impose electoral requirements that effectively disfranchised black voters. From 1890-1910, Southern states ratified constitutional amendments or new constitutions that increased requirements for voter registration, which resulted in disfranchising most blacks and many poor whites (as in Alabama.) With political control in what was effectively a one-party system, they passed Jim Crow laws and instituted racial segregation in public facilities. In 1896, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the defendants in the Plessy v. Ferguson case, which established the "separate but equal" interpretation of provision of services. Without the vote, however, black residents in the South found their segregated facilities consistently underfunded, and they were without recourse in the legal system, as only voters could sit on juries or hold office. They were closed out of the political process in most states. In 1899, the Cumming v. Richmond County Board of Education case ended in the legalization of segregation in schools.

Anti-miscegenation laws prohibited marriages of European-Americans with people of African descent, even if of mixed race. Some states also prohibited marriages across ethnic lines with Native Americans and, later, Asians. Such laws were first passed during the Colonial era in several of the Thirteen Colonies, starting with Virginia in 1691. After the American Revolutionary War, several of the newly independent states repealed such laws. However, all the slave states and many free states enforced such laws in the Antebellum era.

During Reconstruction, when biracial Republican coalitions controlled the legislatures, several Southern states repealed anti-miscegenation laws. As Democrats returned to power, between 1870 and 1884, legislatures passed anti-miscegenation laws in all the states of the Confederacy to re-establish white supremacy.[1]

Western states newly admitted to the Union after the Civil War passed anti-miscegenation laws, often directed against marriages between Europeans and Asians (the increasing immigrant population in that area), as well as prohibiting marriages with blacks and Native Americans. For instance, Utah's marriage law had an anti-miscegenation component passed in 1899; it was repealed in 1963. It prohibited marriage between a white and anyone considered a Negro (Black American), mulatto (half black), quadroon (one-quarter black), octoroon (one-eighth black), "Mongolian" (East Asian), or member of the "Malay race" (a racial classification discriminating against Filipinos). No restrictions were placed on marriages between people of ethnic groups who were not "white persons.".[2]

At the end of the 19th century, sundown towns began to post warnings against blacks staying overnight. Sometimes they passed laws against minorities; in others, they erected signs, such as one posted in the 1930s in Hawthorne, California, which read, "Nigger, Don't Let The Sun Set On YOU In Hawthorne".[3] Discrimination was also accomplished through restrictive covenants for residential areas, agreed to by the real estate agents of the community. In others, the racist policy was enforced through intimidation, including harassment by law enforcement officers.

In addition to the expulsion of African Americans from "sundown towns", Chinese Americans were driven out of some towns. For example, in 1870, ethnic Chinese made up one-third of the population of Idaho, where they had worked on railroads and in mining. Following a wave of violence and an 1886 anti-Chinese convention in Boise, almost none remained by 1910.[4] The town of Gardnerville, Nevada blew a daily whistle at 6 p.m., alerting Native Americans to leave by sundown.[5] Jews were excluded from living in some sundown towns.[6]

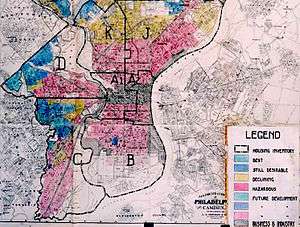

The National Housing Act of 1934 established the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) to try to encourage home ownership during the Great Depression, but another consequence was redlining. In 1935, the Federal Home Loan Bank Board (FHLBB) asked the Home Owners' Loan Corporation (HOLC) to assess 239 cities and develop "residential security maps" to indicate the level of security for real estate investments in each surveyed city. Because of older housing in minority neighborhoods, and undervaluation of minority readiness to work and protect their homes, the agency defined certain areas as high risk. This prevented many residents of minority neighborhoods from being able to get mortgages or loans to renovate their properties. Such redlining had the unanticipated result of increased residential racial segregation and encouraging urban decay in the United States. Urban planning historians theorize that the maps were used for years afterward by public and private entities to deny loans to people in black communities.

The mass immigration to the United States during the late 19th and early 20th centuries led to other restrictive laws, influenced by the nativist movement. The new populations came from eastern and southern Europe and were Catholic and Jewish, as opposed to the majority population in the United States of northern European and African American Protestants. Discriminatory laws were mostly enacted according to national origins, but also involved racial typologies developed by scientific racism theorists. For example, although Indian Americans were not classified as members of any races until the end of the 19th century, the Supreme Court created in 1923, during the United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind case, the official stance to classify Indians as non-white, which at the time retroactively stripped Indians of citizenship and land rights. While the decision was placating racist Asiatic Exclusion League (AEL) demands, spurned by growing outrage at the Turban Tide / Hindoo Invasion [sic] alongside the pre-existing outrage at the "Yellow Peril", and while more recent legislation influenced by the civil-rights movement has removed much of the statutory discrimination against Asians, no case has overturned this 1923 classification. Hence, this classification remains, and is still relevant today because many laws and quotas are race-based.

This period, however, also saw the Yick Wo v. Hopkins case in 1886, which was the first case where the United States Supreme Court ruled that a law that was race-neutral on its face that was administered in a prejudicial manner was an infringement of the Equal Protection Clause.

The 'Yellow Peril' and the national origins formula

Fears and labor competition with Chinese on the West Coast, the alleged "Yellow Peril", led the US Congress to pass the Page Act of 1875, the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, and the Geary Act. The Chinese Exclusion Act replaced the Burlingame Treaty ratified in 1868, which had encouraged Chinese immigration because of labor needs. It provided that "citizens of the United States in China of every religious persuasion and Chinese subjects in the United States shall enjoy entire liberty of conscience and shall be exempt from all disability or persecution on account of their religious faith or worship in either country" and granted certain privileges to citizens of either country residing in the other, withholding, however, the right of naturalization. The Immigration Act of 1917 then created an "Asian Barred Zone" under nativist influence. The Cable Act of 1922 guaranteed independent female citizenship only to women who were married to "alien[s] eligible to naturalization". At the time of the law's passage, Asian aliens were not considered to be racially eligible for U.S. citizenship. As such, the Cable Act only partially reversed previous policies, granting independent female citizenship only to women who married non-Asians. The Cable Act effectively revoked the U.S. citizenship of any woman who married an Asian alien. The National Origins Quota of 1924 also included a reference aimed against Japanese citizens, who were ineligible for naturalization and could not either be accepted on US territory. In 1922, a Japanese citizen attempted to demonstrate that the Japanese were members of the "white race," and, as such, eligible for naturalization. This was denied by the Supreme Court in Takao Ozawa v. United States, who judged that Japanese were not members of the "Caucasian race."

The 1921 Emergency Quota Act, and then the Immigration Act of 1924, restricted immigration according to national origins. While the Emergency Quota Act used the census of 1910, xenophobic fears in the WASP community lead to the adoption of the 1890 census, more favorable to White Anglo-Saxon Protestant (WASP) population, for the uses of the Immigration Act of 1924, which responded to rising immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe, as well as Asia.

One of the goal of this National Origins Formula, established in 1929, was explicitly to keep the status quo distribution of ethnicity, by allocating quotas in proportion to the actual population. The idea was that immigration would not be allowed to change the "national character". Total annual immigration was capped at 150,000. Asians were excluded but residents of nations in the Americas were not restricted, thus making official the racial discrimination in immigration laws. This system was repealed with the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965. However, currently implemented immigration laws are still largely plagued with national origin-based quotas.

During World War II

President Roosevelt enacted discriminatory practices with Executive Order 9066 of February 1942, which paved the way for Japanese American internment during which approximately 120,000 people of Japanese descent (American citizens as well as Japanese nationals) were interned during the war. Americans of Italian and German descent, along with Italian and German nationals, were also interned, but on a much smaller scale (see Italian American internment and German American internment). In Korematsu v. United States (1944), the Supreme Court upheld the Executive Order. It was the first instance of the Supreme Court applying the strict scrutiny standard to racial discrimination by the government and for being one of only a handful of cases in which the Court held that the government met that standard.

Others cases pertaining to Japanese American internment included Yasui v. United States (1943), Hirabayashi v. United States (1943), Ex parte Endo (1944), as well as Korematsu. In Yasui and Hirabayashi, the court upheld the constitutionality of curfews based on Japanese ancestry. In Endo, the court accepted a petition for a writ of habeas corpus and ruled that the War Relocation Authority (WRA, created by Executive Order 9102) had no authority to subject a citizen whose loyalty was acknowledged to its procedures.

Despite these renewed xenophobic fears concerning the "Yellow Peril", 1943 Magnuson Act repealed the Chinese Exclusion Act and allowed naturalization of Asians.

In 1983, the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC) concluded that the incarceration of Japanese Americans had not been justified by military necessity. Rather, the report determined that the decision to detain Japanese Americans had been based on "race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership."

Aftermath of World War II

The United Nations Participation Act of 1945, passed after the victory of the Allies, included provisions that immigration policy should be conducted in a fair manner and non-discriminatory fashion.

In 1946, the Democratic President Harry S. Truman ended racial segregation in the Armed Forces by Executive Order 9981. Later that year, the US Congress passed the Luce-Celler Act of 1946 effectively ending statutory discrimination against Filipino Americans and Indian Americans, who had earlier been considered 'unassimilable' along with most other Asian Americans.

The 1947 Mendez v. Westminster case challenged racial segregation in California schools applied against Latinos. The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeal, in an en banc decision, held that the segregation of Mexican and Mexican-American students into separate "Mexican schools" was unconstitutional. In the 1954 Hernandez v. Texas case, the federal court ruled that Mexican Americans and all other ethnic/"racial groups" in the US had equal protection under the 14th Amendment.

The McCarran-Walter Act of 1952 (or Immigration and Naturalization Act) “extended the privilege of naturalization to Japanese, Koreans, and other Asians.”[7] “The McCarran-Walter Act revised all previous laws and regulations regarding immigration, naturalization, and nationality, and brought them together into one comprehensive statute.”[8]

The civil rights movement

Legislation enacting racial segregation was finally overturned in the 1950s-1960s, after the nation was morally challenged and educated by activists of the Civil Rights Movement. In 1954 with Brown v. Board of Education, the United States Supreme Court ruled that "separate but equal" was inherently discriminatory and directed integration of public schools. An executive order of 1961, by President Kennedy, created the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission to oversee workplace affirmative action. Executive Order 11246 of 1965, signed by President Johnson, enforced this policy. In the 1970s and 1980s, the policy included court-supervised desegregation busing plans.

Over the next twenty years, a succession of court decisions and federal laws, including the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, the 1972 Gates v. Collier Supreme Court ruling that ended racial segregation in prisons, the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (1975) and measures to end mortgage discrimination, prohibited de jure racial segregation and discrimination in the U.S.

The Immigration Act of 1965 discontinued some quotas based on national origin, with preference given to those who have U.S. relatives. For the first time Mexican immigration was restricted.

Residential segregation took various forms. Some state constitutions (for example, that of California) had clauses giving local jurisdictions the right to regulate where members of certain "races" could live. Restrictive covenants in deeds had prevented minorities from purchasing properties from any subsequent owner. In the 1948 case of Shelley v. Kraemer, the US Supreme Court ruled that such covenants were unenforceable in a court of law. Residential segregation patterns had already become established in most American cities, but they have taken new forms in areas of increased immigration. New immigrant populations have typically moved into older areas to become established, a pattern of population succession seen in many areas. It appears that many ethnic populations prefer to live in areas of concentration, with their own foods, stores, religious institutions and other familiar services. People from a village or region often resettle close together in new areas, even as they move into suburban areas.

The American Indian Religious Freedom Act (AIRFA) of 1978 was to preserve the rights of American Indians, Eskimos, Aleuts, and Native Hawaiians to traditional religious practices.[9] Before the AIRFA was passed, certain U.S. federal laws interfered with the traditional religious practices of many American Indians.

Redistricting of voting districts has always been a political process, manipulated by parties or power groups to try to gain advantage. In an effort to prevent African-American populations from being divided to dilute their voting strength and representation, federal courts oversaw certain redistricting decisions in the South for decades to overturn the injustice of the previous century's disfranchisement.

Interpretations continue to change. In the 1999 Hunt v. Cromartie case, the US Supreme Court ruled that the 12th electoral district of North Carolina as drawn was unconstitutional. Determining that it was created to place African Americans in one district (which would have enabled them to elect a representative), the Court ruled that it constituted illegal racial gerrymandering. The Court ordered the state of North Carolina to redraw the boundaries of the district.

See also

- Heart of Atlanta Motel v. United States

- Immigration to the United States

- List of United States immigration legislation

- NAACP v. Alabama

- National Origins Formula

- Racial classification of Indian Americans

- Racism in the United States

- Slavery in the United States

- Smith v. Allwright

- Yick Wo v. Hopkins

References

- ↑ The History of Jim Crow, Jim Crow History website

- ↑ Utah Code, 40-1-2, C. L. 17, §2967 as amended by L. 39, C. 50; L. 41, Ch. 35.

- ↑ Laura Wexler, "Darkness on the Edge of Town", The Washington Post, October 23, 2005, p. BW03, Accessed online 9 July 2006

- ↑ Loewen 2005, Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension of American Racism. New Press. ISBN 1-56584-887-X (page 51).

- ↑ Loewen 2005, page 23

- ↑ Loewen 2005, page 257.

- ↑ “Commentary on Excerpt of the McCarran-Walter Act, 1952”, American Journal Online: The Immigrant Experience, Primary Source Microfilm, (1999), History Resource Center, Farmington Hills, MI: Gale Group, accessed 9 February 2007

- ↑ "McCarran-Walter Act," Dictionary of American History, 7 vols, Charles Scribner's Sons, (1976), History Resource Center, Farmington Hills, MI: Gale Group, accessed 9 February 2007

- ↑ Cornell.edu. "AIRFA act 1978.". Retrieved July 29, 2006.