Keyser Söze

| Keyser Söze | |

|---|---|

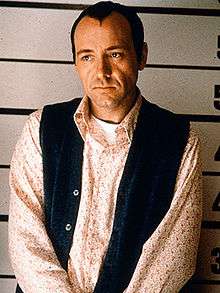

Kevin Spacey's character Roger "Verbal" Kint is identified as Söze in a police sketch | |

| First appearance | The Usual Suspects |

| Created by | Christopher McQuarrie |

| Portrayed by |

Kevin Spacey Scott B. Morgan (flashback)[1] |

| Information | |

| Aliases | Roger "Verbal" Kint |

| Gender | Male |

| Occupation | Drug lord, con artist |

| Nationality | Turkish |

Keyser Söze (/ˈkaɪzər ˈsoʊzeɪ/ KY-zər SOH-zay) is a fictional character and the main antagonist in the 1995 film The Usual Suspects, written by Christopher McQuarrie and directed by Bryan Singer. According to petty con artist Roger "Verbal" Kint (Kevin Spacey), Söze is a crime lord whose ruthlessness and influence have acquired a legendary, even mythical, status among police and criminals alike. Further events in the story make these accounts unreliable, and, in a twist ending, a police sketch identifies Kint's face as Söze. The character was inspired by real life murderer John List and the spy thriller No Way Out, which featured a shadowy KGB mole.

The character has placed in numerous "best villain" lists over the years, including AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes & Villains. Spacey won the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor, turning him from a character actor into a star. Since the release of the film, the character has become synonymous with infamous criminals. Analysis of the character has focused on the ambiguity of his true identity and whether he even exists inside the story's reality. Though the filmmakers have preferred to leave the character's nature to viewer interpretation, Singer has said he believes Kint and Söze are the same person.

Concept and creation

Director Bryan Singer and writer Christopher McQuarrie originally conceived of The Usual Suspects as five felons meeting in a police line-up. Eventually, a powerful underworld figure responsible for their meeting was added to the plot. McQuarrie combined this plot with another idea of his based on the true story of John List, who murdered his family and started a new life. The name was based on one of McQuarrie's supervisors, though the last name was changed. McQuarrie settled on Söze after finding it in a Turkish dictionary; it comes from the idiom "söze boğmak", which means "to talk unnecessarily too much and cause confusion" (literally: to drown in words).[2]

Keyser Söze's semi-mythical nature was inspired by Yuri, a rumored KGB mole whose existence nobody can confirm, from the spy thriller No Way Out.[3] Kint was not originally written to be as obviously intelligent; in the script, he was, according to McQuarrie, "presented as a dummy".[4] Spacey and Singer had previously met at a screening for Public Access. Spacey requested a role in Singer's next film, and McQuarrie wrote the role of Kint specifically for him. McQuarrie said he wanted audiences to dismiss Kint as a minor character, as Spacey was not yet well-known.[5] Spacey made it more obvious that the character is holding back information, though the depth of his involvement and nature of his secrets remain unrevealed. McQuarrie said that he approved of the changes, as it makes the character "more fascinating".[4]

Fictional history

The Usual Suspects consists mostly of flashbacks narrated by Roger "Verbal" Kint (Kevin Spacey), a disabled con artist. Verbal has been granted immunity from prosecution provided he assists investigators, including Customs Agent David Kujan (Chazz Palminteri) and reveals all details of his involvement with a group of career criminals who are assumed to be responsible for the destruction of a freighter ship and the murder of nearly everyone on board. While Kint is telling his story, Kujan learns the name Keyser Söze from FBI agent Jack Baer (Giancarlo Esposito) and demands Kint tell him what he knows.

According to Kint, Söze began his criminal career as a petty drug dealer in his native Turkey. His legendary persona is born when rival Hungarian smugglers invade his house while he is away, rape his wife, and hold his children hostage; when Söze arrives, they kill one of his children and demand he surrender his business. Instead, Söze kills his own family and all but one of the Hungarians, who he knows will tell the Mafia what has happened. Once his family is buried, Söze targets the Hungarian Mafia, their families, friends, and people who owe them money. He goes underground, never again doing business in person.

Söze's ruthlessness is legendary; Kint describes him as having had enemies and disloyal henchmen brutally murdered, along with everyone they hold dear, for the slightest infractions, and he personally murders anyone who can identify him. Even his own henchmen often do not know for whom they work. Over the years, his criminal empire flourishes, as does his legend; remarking on Söze's mythical nature, Kint says, "The greatest trick the Devil ever pulled was convincing the world he didn't exist",[6] a line borrowed from Charles Baudelaire.[7]

Kint describes how he and his cohorts are blackmailed by Söze, through Söze's lawyer Kobayashi (Pete Postlethwaite), into destroying a large drug shipment belonging to Söze's Argentinian rivals. All but Kint and a Hungarian are killed in the attack. Baer believes there were no drugs and the true purpose of the attack was to eliminate a passenger who could identify Söze. Kujan confronts Kint with the theory that Söze is one of the four other criminals with whom Verbal had worked: a corrupt former police officer and professional thief named Dean Keaton (Gabriel Byrne). Kujan's investigation of Keaton is what involved him in the case.

In the final sequence, it is revealed that the story that Kint had told Kujan is a fabrication, made up of strung-together details culled from a crowded bulletin board in a messy office. The surviving Hungarian describes Söze to a sketch artist: the drawing faxed in to the police station closely resembles Kint. Kujan realizes the fabrication and pursues Kint, who has already been released, his limp gone. He enters a car, driven by "Kobayashi". As the two drive away, Kujan desperately looks around the crowded streets for him.

Reception and legacy

A. O. Scott of The New York Times called him the "perfect postmodern sociopath",[8] and Quentin Curtis of The Independent described him as "the most compelling creation in recent American film".[9] Jason Bailey of The Atlantic identified the role as turning Kevin Spacey from a character actor to a star.[10] Kevin Spacey received the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor for his performance.[11]

The character placed 48th in the American Film Institute's "AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes & Villains" in June 2003.[12] Time placed him at #10 on their list of most memorably named film characters[13] and #5 in best pop culture gangsters.[14] Entertainment Weekly ranked the character #37 in their list of the 100 greatest characters of the past twenty years,[15] #6 in most vile villains,[16] and #12 in the best heroes and villains.[17] Ask Men ranked him #6 in their list of top ten film villains.[18] Total Film ranked him #37 in their best villains [19] and #40 in best characters overall.[20] MSN ranked him #4 in their list of the 13 most menacing villains.[21] Empire ranked him #41 in their "100 Greatest Movie Characters" poll.[22]

Analysis

In an interview with Metro Silicon Valley, Pete Postlethwaite quoted Bryan Singer as saying that all the characters are Söze. When asked point blank whether his character is Söze, Postlethwaite said, "Who knows? Nobody knows. That's what's good about The Usual Suspects."[23] Spacey has also been evasive about his character's true identity. In an interview with Total Film, he said, "That's for the audience to decide. My job is to show up and do a part – I don't own the audience's imagination."[24] Singer said the film is ambiguous about most of the character's details, but the fax sent at the end of the film proves in his mind that Kint is Söze.[25]

Bryan Enk, writing for UGO, states that the myth-making story of Söze's origins is a classic ghost story that would be right at home in horror fiction.[6] Writing about psychopaths in film, academic Wayne Wilson explicitly compares Söze to Satan and assigns to him demonic motives. Wilson states that Söze allows himself to be caught just to prove his superiority over the police; this compromises his ultimate goal of anonymity, but Söze can not resist the urge to show off and create mischief.[26] In The Journal of Nietzsche Studies, Lewis Call states that Söze's mythological status draws the ire of the authoritarian government agents because he "represents a terrifying truth: that power is ephemeral, and has no basis in reality."[27] According to Call, Söze's intermediaries – the "usual suspects" themselves – are more useful to the police, as they represent an easily controlled and intimidated criminal underworld, in direct contrast to Söze himself.[27]

Hanna M. Roisman compares Kint to Odysseus, capable of adapting both his personality and his tales to his current audience. Throughout his tale, Kint adapts his confession to Kujan's revealed biases. Roisman draws direct parallels to Odysseus' tales to the Phaeacians: like Odysseus, Kint allows his audience to define him and his narrative. Appealing to Kujan's arrogance, Kint allows himself to be outwitted, humiliated, and broken by his interrogator; Kint further invents a mythical villain that he credulously believes in and gives Kujan the privileged perspective of the skeptic. Kint thus creates a neo-noir thriller inside of a neo-noir thriller and demonstrates the artificiality of storytelling.[28] Benjamin Widiss identifies post-structural elements to the film, such as the lack of a clear protagonist throughout much of the film. This extends to ambiguity over Kint's role as author or reader, and whether he is Kint pretending to be Söze or the reverse.[29]

Söze was also subject to detailed fan analysis and debate. Fans contacted Singer personally and quizzed him on explanations for the film's complicated plot.[30] Fan theories about Söze's identity became a popular topic on internet forums.[1] After the film's festival premiere, the ambiguity of Söze's identity and how to pronounce his name were used in the film's marketing. Pronunciation had previously been an issue for distributor Gramercy Pictures, who used, "Who is Keyser Söze?" to demonstrate both proper pronunciation and stoke speculation.[30] The ad campaign was later highlighted by Entertainment Weekly as "question of the year" for 1995.[31]

In popular culture

Since the release of the film, the name "Keyser Söze" has become synonymous with a feared, elusive person nobody has met.[32] In June 2001, Time referred to Osama bin Laden as "a geopolitical Keyser Söze, an omnipresent menace whose very name invokes perils far beyond his capability".[33]

The term has also been used as a verb, with a character in television series Buffy the Vampire Slayer asking "Does anyone else feel like they've been Keyser Soze'd?", referring to a sense of having been definitively manipulated and outmaneuvered.[34]

In his 1999 review of Fight Club, which was generally negative, film critic Roger Ebert commented, "A lot of recent films seem unsatisfied unless they can add final scenes that redefine the reality of everything that has gone before; call it the Keyser Söze syndrome."[35]

References

- 1 2 Mottram, James (2006). The Sundance Kids: How the Mavericks Took Back Hollywood (1st American paperback ed.). NY: Faber and Faber, Inc. pp. 115–116. ISBN 0865479674.

- ↑ Anastasia, George; MacNow, Glen (2011). "Chapter 9: The Usual Suspects". The Ultimate Book of Gangster Movies: Featuring the 100 Greatest Gangster Films of All Time. Philadelphia: Running Press. ISBN 9780762443703.

- ↑ Hoad, Phil (4 January 2016). "How we made The Usual Suspects". The Guardian. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- 1 2 Spirou, Penny (2014). ""I'm Not a Celebrity. That's Not a Profession. I'm an actor": Kevin Spacey from The Usual Suspects (1995) to Beyond the Sea (2004)". In Barlow, Aaron J. Star Power: The Impact of Branded Celebrity. ABC-CLIO. p. 143. ISBN 9780313396182.

- ↑ Snider, Eric D. (16 August 2015). "14 Unusual Facts About 'The Usual Suspects'". Mental Floss. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- 1 2 3 Enk, Bryan (1 October 2009). "The Usual Suspects: The Legend of Keyser Soze". UGO. Archived from the original on September 26, 2011. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ↑ Baudelaire, Le Joueur Généreux, where the Devil recounts to a gambler that he has even heard a preacher (plus subtil que ses confrères) cry: "Mes chers frères, n'oubliez jamais, quand vous entendrez vanter le progrès des lumières, que la plus belle des ruses du diable est de vous persuader qu'il n'existe pas!" French text on Wikisource Neither McQuarrie nor Singer realized this at the time and included it after hearing others paraphrase the quotation.[6]

- ↑ Scott, A. O. (21 October 2011). "Bad Times on Wall Street, Boom Times for Kevin Spacey". New York Times. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ↑ Curtis, Quentin (27 August 1995). "Confused? You Will Be". The Independent. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ↑ Bailey, Jason (17 October 2012). "Keyser Söze's Big Break: The Roles That Made Character Actors Into Stars". The Atlantic. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ↑ Grimes, William (26 March 1996). "Gibson Best Director for 'Braveheart,' Best Film". New York Times. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- ↑ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes and Villains". American Film Institute. Retrieved 19 March 2010.

- ↑ "Top 10 Memorable Movie-Character Names". Time. 22 January 2012. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ↑ Webley, Kayla (17 September 2010). "Top 10 Pop-Culture Gangsters". Time. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ↑ Vary, Adam B. (1 June 2010). "The 100 Greatest Characters of the Last 20 Years: Here's our full list!". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ↑ Harris, Annika (19 July 2012). "50 Most Vile Movie Villains: 6. Keyser Söze". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ↑ "Good Guys vs. Bad Guys: Who Wins?". Entertainment Weekly. 7 June 2010. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ↑ Simpson, Matthew. "Top 10: Movie Villains". Ask Men. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ↑ BANG Showbiz (26 November 2007). "Top Heroes and Villains Named in Movie List". News.com.au. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ↑ "The Total Film Top 100 Movie Characters Of All Time – 50 to 26". Total Film. 28 September 2007. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ↑ Hunter, Melissa (12 July 2010). "Hollywood's 13 Most Menacing Villains". MSN. Archived from the original on July 16, 2010. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ↑ "The 100 Greatest Movie Characters". Empire. Retrieved 2008-12-02.

- ↑ von Busack, Richard (29 May 1997). "Unusual Suspect". Metro Silicon Valley. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ↑ "The Total Film Interview – Kevin Spacey". Total Film. 1 December 2004. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ↑ Staskiewicz, Keith (18 August 2015). "Bryan Singer remembers The Usual Suspects on its 20th anniversary". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 26 February 2016.

- ↑ Wilson, Wayne (1999). The Psychopath in Film. University Press of America. pp. 251–255. ISBN 0-7618-1317-9.

- 1 2 Call, Lewis (Spring 2001). "Toward an Anarchy of Becoming: Postmodern Anarchism in Nietzschean Philosophy". The Journal of Nietzsche Studies. Penn State University Press (21): 52–53. JSTOR 20717753. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Roisman, Hanna M. (2001). "Verbal Odysseus: Narrative Strategy in The Odyssey and The Usual Suspects". In Winkler, Martin M. Classical Myth & Culture in the Cinema. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 51–54, 63–68. ISBN 9780195351569.

- ↑ Widiss, Benjamin (2011). "Seven and The Usual Suspects". Obscure invitations The Persistence of the Author in Twentieth-Century American Literature. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press. pp. 156–157. ISBN 0804773238.

- 1 2 Gordinier, Jeff (29 September 1995). "Behind the scenes: The Usual Suspects". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 26 February 2016.

- ↑ Barrett, Annie (26 June 2010). "1995: A Special Year?". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 26 February 2016.

- ↑ Griggs, Brandon (17 August 2015). "Why Keyser Söze still rules, 20 years later". CNN. Retrieved 26 February 2016.

- ↑ Karon, Tony (20 June 2001). "Bin Laden Rides Again: Myth vs. Reality". Time. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- ↑ Adams, Michael (2003). Slayer Slang: A Buffy the Vampire Slayer Lexicon. Oxford University Press. p. 193. ISBN 0-19-517599-9.

- ↑ Ebert, Roger (15 October 1999). "Fight Club". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Keyser Söze |