Khanjar

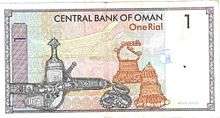

A khanjar (Arabic: خنجر, Persian: خنجر, Turkish: Hançer) is a traditional dagger originating from Oman. Worn by men for ceremonial occasions, it is a short curved sword shaped like the letter "J" and resembles a hook. It can be made from a variety of different materials, depending on the quality of its craftsmanship. It is a popular souvenir among tourists and is sold in souqs throughout the region. A national symbol of the sultanate, the khanjar is featured on the country's national emblem and on the Omani rial. It is also utilized in logos and commercial imagery by companies based in Oman.

History

Although it is not known when the Omani khanjar was first created, rock carvings epitomizing the dagger were found on gravestones located in the central part of the Ru’us al Jibal region. These are believed to have predated the Wahhabi revival, which occurred in the late 1700s.[1] They were also mentioned in an account by Robert Padbrugge of the Dutch Republic, who journeyed to Muscat in June 1672.[2] Historically, only men from the royal family could wear the khanjar.[3] However, all civilian men were permitted to do so after 1970,[3] the year when Qaboos bin Said al Said – the current Sultan of Oman – overthrew his father Said bin Taimur and began to institute reforms to modernize the country.[4][5]

Usage and symbolism

Composition and manufacturing

Depending on the quality of its craftsmanship, the Omani khanjar can be made using a variety of different metals and other materials. Gold or silver would be used to make khanjar of the finest quality (e.g. for royalty), while brass and copper would be utilized for daggers made by local craftsmen.[6] For instance, a sheath adorned with gold was historically limited to the Omani upper class.[7] Traditionally, the dagger is designed by its future owner himself, with the craftsman taking into account the "specifications" and "preferences" stipulated by the former. The time it takes to manufacture a khanjar can range from three weeks to several months.[2]

The most elemental sections of the khanjar are its handle and blade,[8] with the material utilized in the former playing a significant role influencing the final price of the dagger.[7] Bone – specifically rhinoceros horn and elephant tusk[7] – was once the common standard, as it was "considered the best material" to make the hilt out of.[8] However, with the international ban on the ivory trade, the usage of other materials – such as wood, plastic, and camel bone – has become more prevalent.[2][7][8] Typically, the top of the hilt is flat, but the one designed for the royal family is in the shape of a cross.[8]

Custom

The Omani khanjar is tucked underneath a waist belt and is situated at the front and centre of the wearer's body.[9] It used to form part of everyday attire;[10] however, it is now carried as a "ceremonial dagger",[11] and worn only for formal events and ceremonies – such as weddings, parades, meetings, and diplomatic functions – among many other occasions.[2][12] Labelled a "ubiquitous sign of masculinity" by John M. Willis in the The Arab Studies Journal,[13] the khanjar is a symbol of "manhood, power and authority",[7] as well as serving as a status symbol for the person wearing it.[2][10] As a result, it is sometimes given by families to their sons when they reach adolescence,[10] and is a common wedding gift to the groom.[3]

Although the khanjar was originally created as a weapon to attack and defend, it is utilized solely for ceremonial and practical purposes today.[8] The latter situation would occur in the desert, where it is used as a tool for hunting and skinning animals, as well as for slicing ropes.[12] Because of this development, it is now considered a "social taboo" in Oman to pull out one's khanjar from its scabbard, since the only time men would do this would be to seek vengeance or to defend oneself.[10]

Distribution

While the khanjar is most prevalent in Oman given its symbolic status there,[10] it is also worn by men in Yemen and the United Arab Emirates, forming an integral component of "traditional dress" in those countries.[14][15] It can also be found and is sold in other Gulf Arab states, such as the Souq Waqif in Doha, Qatar.[16] The khanjar is a popular keepsake among tourists,[2] and is the Sultanate's best-selling memento.[17]

Other uses

Official government

As the khanjar is a national symbol of Oman, it is featured on the sultanate's national emblem.[2][10][18] It has been a symbol on the royal crest of the Al Said dynasty since the 18th century,[7] which subsequently became the national emblem.[9] It is also depicted on the Omani rial[7] – the country's currency – specifically on the one rial note,[19] as well as on postage stamps issued by the sultanate.[2] Furthermore, there are statues of khanjar on buildings housing government ministries and at various roundabouts throughout the country.[2][7]

Commercial

The khanjar was previously shown prominently on the logo[2] and planes[7] of Oman Air – the country's flag carrier[20] – until it was removed under a rebranding in 2008.[21] The logo of Omantel also illustrates a stylized khanjar; it was retained in the logotype's motif after the telecommunications company merged with Oman Mobile in 2010.[22] Moreover, the perfume company Amouage – which is owned by the Sultan of Oman and his royal family[23] – incorporates the dagger into the design of its bottles. The cap on its Gold for Men perfume bottle resembles the handle of a khanjar, complimenting the Gold for Women cap which evokes the dome of Ruwi Mosque.[24]

See also

References

- ↑ Lancaster, William; Lancaster, Fidelity (November 2011). "A discussion of rock carvings in Ra's al Khaimah Emirate, UAE, and Musandam province, Sultanate of Oman, using local considerations". Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy. John Wiley & Sons. 22 (2): 166–195. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0471.2011.00338.x. Retrieved June 2, 2014. (registration required)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Kola, Aftab H. "Symbol of manhood". Deccan Herald. Retrieved May 30, 2014.

- 1 2 3 Turbett, Peggy (September 7, 2008). "A modern air of mysticism in the land of frankincense". The Star-Ledger. New Jersey. p. 3. Retrieved May 31, 2014. (subscription required)

- ↑ Crystal, Jill Ann (January 21, 2014). "Oman – Contemporary Oman". Encyclopedia Britannica. Encyclopedia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved May 31, 2014. (subscription required)

- ↑ "History of Oman". Lonely Planet. Retrieved May 31, 2014.

- ↑ "More needed to be done for the survival of Omani art, crafts". Times of Oman. Times News Service. October 7, 2012. Retrieved June 3, 2014. (subscription required)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Hiel, Betsy (May 27, 2007). "Old & New". Pittsburgh Tribune-Review. Retrieved May 30, 2014. (subscription required)

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hawley, Ruth (July 1975). "Omani Silver". Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies. Archaeopress. 6: 84. JSTOR 41223172. Retrieved February 12, 2014. (registration required)

- 1 2 Chatty, Dawn (May 2009). "Rituals of Royalty and the Elaboration of Ceremony in Oman: View From the Edge" (PDF). International Journal of Middle East Studies. Cambridge University Press. 41 (1): 10. Retrieved June 3, 2014. (registration required)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Kamal, Sultana (February 27, 2013). "Khanjar (Dagger): Truly "Iconic" Omani emblem". Times of Oman. Archived from the original on May 30, 2014. Retrieved May 30, 2014.

- ↑ Rogers, Stuart (January 31, 2013). "Holidays in Oman: experience endless beauty". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved June 5, 2014.

- 1 2 Morgan, Judith (August 15, 1999). "Nizwa souk is lower key than most, but just as intriguing". The San Diego Union-Tribune. p. F4. Retrieved May 30, 2014. (subscription required)

- ↑ Willis, John M. (Spring 1996). "History, Culture, and the Forts of Oman". The Arab Studies Journal. Arab Studies Institute. 4 (1): 143. JSTOR 27933683. Retrieved February 12, 2014. (registration required)

- ↑ Picton, Oliver James (February 2, 2010). "Usage of the concept of culture and heritage in the United Arab Emirates – an analysis of Sharjah heritage area". Journal of Heritage Tourism. Routledge. 5 (1): 74. doi:10.1080/17438730903469813. Retrieved February 12, 2014. (registration required)

- ↑ Karlgård, Tone Simensen; Ball, Marieanne Davy (2011). "Typical souvenirs, originals or copies, how do we know?" (PDF). Stop heritage crime – Good practices and recommendations. Interpol: 129. ISBN 978-83-931656-5-0. Retrieved June 2, 2014. replacement character in

|url=at position 30 (help) - ↑ "Is Qatar the Next Dubai?". The New York Times. June 4, 2006. Retrieved May 30, 2014.

- ↑ Blackerby, Cheryl (March 26, 2000). "Only 15 Readers Got All 30 Answers". The Palm Beach Post. p. 12D. Retrieved June 3, 2014. (subscription required)

- ↑ "Oman". The World Factbook. CIA. Retrieved May 30, 2014.

- ↑ Cuhaj, George S., ed. (February 17, 2012). 2013 Standard Catalog of World Paper Money – Modern Issues: 1961–Present, Volume 3. Krause Publications. p. 769.

- ↑ "Oman to restructure organisation of its civil aviation sector". Centre for Aviation. September 12, 2012. Archived from the original on September 25, 2012. Retrieved May 31, 2014.

- ↑ Jones, Jeremy (January 1, 2012). Oman, Culture and Diplomacy. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 259–260.

- ↑ "Oman Mobile, Omantel merge, unveil new logo". Times of Oman. Times News Service. February 9, 2010. Retrieved May 31, 2014. (subscription required)

- ↑ Deane, Daniela (February 25, 2010). "Oman's royal family scents global profit in luxury perfumes". CNN. Turner Broadcasting System. Retrieved May 31, 2014.

- ↑ Chee, Kee Hua (September 4, 2011). "The smell of luxury". The Star. Malaysia. Archived from the original on May 31, 2014. Retrieved May 31, 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kanjar. |

- Khanjar photos at Alain-Dailyphoto Blogspot

- Press release showing the khanjar on Oman Air's old logo