Knight Foundry

|

Knight's Foundry and Shops | |

|

Knight Foundry exterior | |

| |

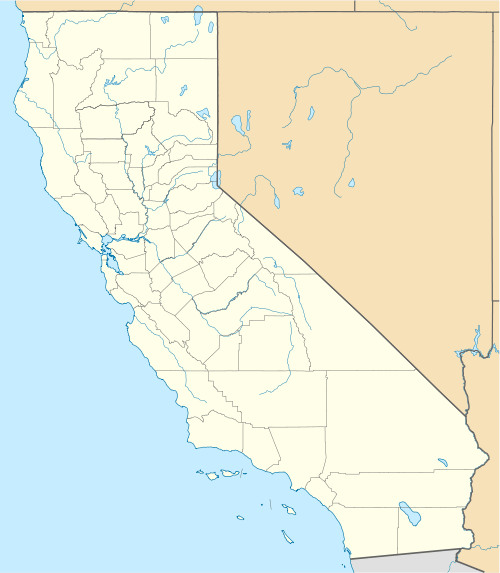

| Location | Sutter Creek, CA |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 38°23′36″N 120°47′1″W / 38.39333°N 120.78361°WCoordinates: 38°23′36″N 120°47′1″W / 38.39333°N 120.78361°W |

| Built | 1873 |

| Architect | Samuel N. Knight |

| NRHP Reference # | 75000423 [2] |

| CHISL # | 884[1] |

| Added to NRHP | July 1, 1975 |

Knight Foundry, also known as Knight's Foundry and Shops, is a cast iron foundry and machine shop in Sutter Creek, California. It was established in 1873 to supply heavy equipment and repair facilities to the gold mines and timber industry of the Mother Lode. Samuel N. Knight developed a high speed, cast iron impulse water turbine which was a forerunner of the Pelton wheel design. Knight Wheels were used in some of the first hydroelectric plants in California, Utah, and Oregon. This site is the last water-powered foundry and machine shop in the United States.[3] A 42-inch (107 cm) Knight Wheel drives the main line shaft, with smaller water motors powering other machines.

History

Samuel Knight came west to California from Maine in 1863. His Knight Wheel was the first kind of water turbine where a high-pressure nozzle from which the water originated was aimed slightly off-center to the cups that caught the water, allowing the energy created by water's splashing not to be wasted.[4] By the 1890s, more than 300 Knight Wheels had been produced and were in widespread use across the Western United States.

Lester Allan Pelton's competing Pelton Wheel was developed in 1878, based on a similar concept, but using two cups side-by-side and having the nozzle pointed directly between the cups. It turned out to be more efficient, the two types having been directly compared in a competition in 1883. The Pelton Wheel went on to become the industry standard. Recognizing the superior design, Knight developed an improved electrical governor that controlled the flow of water to the nozzle for any type of impulse water turbine.[5]

During the California Gold Rush, the foundry was just one of many such in the area, producing items necessary for times, such as mining equipment and street lights for the growing region. As the years passed and the gold was exhausted, the foundry stayed in business by creating specialized parts that could not be easily mass-produced.[3] Additionally, Knight invented several other types of mining equipment, with the foundry having a total of eight patents for machines designed in his shop, one of them being after Knight's death. Knight dredger pumps were used in San Francisco Bay, Puget Sound, and the Willamette and Columbia Rivers.[4]

Knight died in 1913 and left the ownership of the foundry to his employees, and it stayed in employee hands until 1970 when the last employee-owner died. At that point, it was purchased by Carl Borgh, an aerospace engineer from Southern California who was originally a customer.

The foundry stayed in business until 1996 when Borgh retired, after which it survived for a while as a museum, but there was not enough business to offset the high insurance costs of the equipment. Borgh died in 1998 and his estate sold the company to Richard and Melissa Lyman in 2000, a couple who was in the business of preserving old buildings. Their purchase was simply to hold it until a non-profit organization founded by Andy Fahrenwald, a filmmaker who had come to create a documentary film about the foundry, had enough funds to purchase it. However, Fahrenwald's organization could never raise enough money. In 2007 the City of Sutter Creek agreed to buy it from the Lymans,[3] but could not come to an agreement on terms suitable to both parties, and negotiations ended in August 2010.[6]

Process

Wood craftsmen begin by making a model of the desired metal object from hardwood, using lathes, saws, and planes, which were all powered by the Knight Wheels. The model, called a pattern, is then placed in a casting flask, in its simplest form a topless and bottomless box split in half around its perimeter. The flask is placed on a board and a sand mixture (containing seacoal, bentonite clay, and pitch) poured and rammed around the pattern. The additives harden and stabilize the sand so that the flask can be split apart and the pattern removed leaving an exact impression or mold in the sand. The pattern can be reused almost indefinitely to create more molds in additional casting flasks. A channel or gate is left in the sand so that when the flask is rejoined, the ironworkers can pour the molten iron into it through the opening. When the iron has solidified the flask is broken apart, destroying the sand mold in the process, to reveal the rough casting.

Present status

The foundry is registered as a California Historical Landmark.[1] and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. It is also designated a Mechanical Engineering Historic Site by the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME),[7] and has been declared one of America's Most Endangered Places by the Smithsonian Institution.[5]

References

- 1 2 3 "Knight Foundry". Office of Historic Preservation, California State Parks. Retrieved 2012-03-30.

- ↑ National Park Service (2007-01-23). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- 1 2 3 Bailey, Eric (August 8, 2007). "Old foundry a diamond in the rough". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2008-11-20.

- 1 2 "Historic Knight Foundy: A National Historic Mechanical Engineer Landmark" (PDF). American Society of Mechanical Engineers. February 25, 1995. Retrieved 2008-11-20.

- 1 2 "Knight Foundry and Sutter Creek". Sierra Nevada Virtual Museum. Retrieved 2008-11-20.

- ↑ "Sutter Creek Ends Knight Foundry Property Negotiations". TSPN TV. 5 August 2010. Retrieved 8 November 2013.

- ↑ "#182 Knight Foundry and Machine Shop (1873)". American Society of Mechanical Engineers. Retrieved 2008-11-20.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Knight Foundry. |