Kupe

In the Māori mythology of some tribes, Kupe (10th century) was involved in the Polynesian discovery of New Zealand.

Contention

There is contention concerning the status of Kupe. The contention turns on the authenticity of later versions of the legends, the so-called 'orthodox' versions closely associated with S. Percy Smith and Hoani Te Whatahoro Jury. Unlike the attested tribal traditions about Kupe recorded before Smith and Jury, the orthodox version is precise in terms of dates and in offering placenames in Polynesia where Kupe is supposed to have lived or departed from. The orthodox version also places Kupe hundreds of years before the arrival of the other founding canoes, whereas in the earlier traditions, Kupe is most definitely contemporary with those canoes (Simmons 1976). In addition, according to legends of the Whanganui and Taranaki regions Kupe was a contemporary of Turi of the Aotea canoe. In other traditions, Kupe arrived around the year 1400 on other canoes, including Tainui and Tākitimu (Simmons 1976:20–25).

The orthodox version

In the "orthodox" version, Kupe was a great chief of Hawaiki who arrived in New Zealand in 925 AD. He left his cousin Hoturapa to drown during a fishing expedition and kidnapped his wife, Kuramarotini, with whom he fled in her great canoe Matawhourua. During their subsequent journeys, they overcame numerous monsters and sea demons, including the great octopus named as Te Wheke-a-Muturangi, and discovered New Zealand. Returning to Hawaiki, Kupe told of his adventures and convinced others to migrate with him (Craig 1989:127; see also External links below).

David Simmons said "A search for the sources of what I now call 'The Great New Zealand Myth' of Kupe, Toi and the Fleet, had surprising results. In this form they did not exist in the old manuscripts nor in the whaikorero[2] of learned men. Bits and pieces there were. Kupe was and is known, in the traditions of the Hokianga, Waikato, East Coast and South Island: but the genealogies given did not tally with those given by S. Percy Smith. The stories given by Smith were a mixture of differing tribal tradition. In other words the whole tradition as given by Smith was pakeha, not Maori. Similarly, the story of Toi and Whatonga and the canoe race leading to settlement in New Zealand could not be authenticated except from the one man who gave it to Percy Smith. Learned men of the same tribe make no mention of this story and there are no waiata[3] celebrating their deeds. Tribal origin canoes are well known to the tribes belonging to them: but none of them talk as Smith did of six large sea-going canoes setting out together from Raiatea. The Great New Zealand Myth was just that". (Simmons 1977).

Attested local traditions

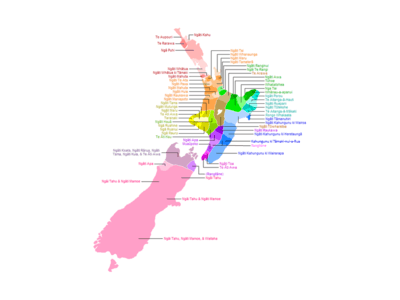

Traditions about Kupe appear among the peoples of the following areas: Northland, Ngāti Kahungunu, Tainui, Whanganui-Taranaki, Rangitāne, and the South Island.

Northland

In the Northland traditions, Kupe is a discoverer and contemporary with, but older than, Nukutawhiti, the ancestor of the Ngā Puhi people. Kupe arrives, lives at Hokianga, and returns to Wawauatea, his homeland, leaving certain signs and marks of his visit (Simmons 1976:34).

- A reference to Kupe occurs in a version of the legend of Māui fishing up the North Island, recorded in 1841 by Catherin Servant, a Marist missionary. Māui’s hook, made from the jawbone of his eldest son, catches in the gable of the house of Nukutawhiti, Kupe’s wife. Kupe was involved in the formation of New Zealand (from Māui’s fish).[4]

- In 1849 Āperahama Taonui of Ngā Puhi wrote that 'Kupe came to this land in olden times' to look for Tuputupuwhenua.[5] 'He went to all places on this island. He did not see Tuputupuwhenua on this land. Hokianga was seen, a returning of Kupe, that is (the meaning of) Hokianga. Under the earth are his and Kui’s dwelling’. The land was uninhabited (deserted). Āperahama adds a genealogy from Kupe to Nukutawhiti, the ancestor of the Ngā Puhi.[6] Nukutawhiti came ‘from overseas’ with his brother-in-law Ruanui in their canoe named Mamari. They met Kupe at sea, who told Nukutawhiti that Tuputupuwhenua was at Hokianga. When Nukutawhiti arrived at the mouth of the harbour, Tuputupuwhenua disappeared underground (Simmons 1976:29–30).[7]

- Hoani Timo wrote a manuscript in 1855 in which 'Kupe came in former times – he was the husband of Peketahi; they crossed over from the other side' (of the sea). They lost a child, Totoko, at sea. When they arrived they had more children - Māui-mua, Māui-taha, and Māui-tikitiki-a-Taranga. Rāhiri, an important ancestor of Ngā Puhi, descends from these children (Simmons 1976:31)[8]

- A tradition collected before 1855 from an unknown author names Kupe's home island as Wawauatea. Kupe came and visited every part of this island. He lived at Hokianga until he returned home. He left several things behind, including his canoe bailer,[9] and two of his pets at the mouth of the Hokianga harbour: Āraiteuru (male) and Nuia (female). On his return to Wawauatea he informed the men of the village that there was a good land to the south. Canoes were made, of which Matawhaorua, belonging to Ngā Puhi, landed at Hokianga. Other canoes are mentioned with details of their sailings (Simmons 1976:31).[8]

- Simmons had access to a privately held manuscript from the Hokianga area[10] which says that there were three Kupe in Hawaiki: Kupe Nuku, Kupe Rangi, and Kupu Manawa.[11] Kupe Nuku came to this island in the Matahourua canoe, with his wife, two slaves, and nine others, with their wives.[12] They took three days and nights to paddle to this island, Aotearoa. Kupe sailed around the whole island and saw no people. He left signs along the coast to show that they were the first to live there. At Hokianga he left the posts of his net and his earth oven, the footprints of his slave, and the bailer of his canoe. At Opara, he left his dog.[13] When fish were baked in an oven, Kupe grew angry when the oven was opened and they were not cooked. He cursed his companions, sending the birds and lizards and insects into the forest to live, the spirit folk to the mountains, and the echo to the cliffs where he would be condemned to utter short speeches as he had done as his friends neglected the oven. Kupe returned to Hawaiki, but war broke out because of Tama-te-kapua. As a result, Kupe's grandson Nukutawhiti leaves Hawaiki and lands in Hokianga (Simmons 1976:33–34).[14]

Ngāti Kahungunu

Early accounts from the Ngāti Kahungunu area consistently place Kupe on board the Tākitimu canoe or name as his companions people who are strongly associated with the Tākitimu. No other canoes are mentioned in connection with him. They also contain no references to the octopus of Muturangi, nor of the chase from Hawaiki (Simmons 1976:20).

- In a manuscript written by Hami Ropiha in 1862 (Simmons 1976:19–20), Tamatea came on the Tākitimu canoe, along with his elders, the children of Tato, who were Rongokako, Hikitapuae, Hikitaketake, Rongoiamoa, Taihopia, Kahutuanui, Mataro, Te Angi, Kupe, Ngake, Paikea, and Uenuku. They came to ‘this island’ for two reasons: a fight about a woman, and a dispute over the planting of crops. At Tauranga, the group divided in three. Tamatea and his son Kahungunu stayed to make a fishing net, others went north, but Kupe and Ngake sailed to the south in Tākitimu. At Wairoaiti, the family had been sent inland to weave flax fibre for the canoe. When they returned, the canoe was gone. They climbed a hill and saw the canoe sailing away. Kupe arrived at Tawake. He sent his daughter Mokototuarangi to fetch water. When she was returning, Kupe’s canoe sailed off and the daughter was left standing there, angry.[15]

He then traveled south to reach Mahia.

Tainui

Tainui traditions about Kupe can be summarised as: Kupe stole Hoturapa’s wife or wives; came to New Zealand and cut up the land; raised rough seas; and went away again. The sources in detail:

- In a South Manukau tradition dated to 1842 (Simmons 1976:20–21),[16] Kupe came with his grandfather, Maru-tawiti, and his brother-in-law Hoturapa and several others. They came to survey the land and return again. Nothing is known of the land from which they sailed. Kupe is said to have stranded his brother-in-law at East Cape, stealing away with his wives. He sailed around North Cape. Kupe raised a rough sea on the western coast to prevent Hoturapa from following him, and that is why the west coast is always rougher than the east coast. At the Manukau Heads he struck Paratutae rock with his paddle, leaving an imprint which is visible to this day. The journey ended at Kāwhia. Little more is known of Kupe; perhaps he returned to the land from which he came. It is said that some of his people remained.

- A tradition of the Ngāti Te Ata tribe, also dated 1842, and also from the South Manuaku area (Simmons 1976:21),[17] places Kupe on board the Tainui canoe.

- A song collected from the Ngāti Toa war leader Te Rauparaha in 1847 refers to Kupe as the ‘man who sliced up the land; Kapiti stands away, Mana stands away, Arapaoa stands separated. These are the signs of my ancestor, of Kupe, who explored Titapua’ (Simmons 1976:21–22).

- A version showing some influence from printed sources was collected before 1907 from Wirihana Aoterangi of the Ngāti Tahinga tribe of Raglan (Simmons 1976:22–23).[18] Kupe and his companion Turi arrive on a canoe named Aotearoa. They find the inhabitants of this island to be ‘goblins’ or ‘fairies’ of various kinds,[19] the descendants of the companions of Māui when he fished up this island. Kupe left his daughter at Rangitoto. Near Whanganui-a-tara (Wellington Harbour) he regretted this, and cut his flesh. The blood gushed forth and to this day the cliffs and sea creatures of that area are red. At Aotea Harbour he discovered the inhabitants, the Ngāti Matakore, digging up fern-root. Kupe decided to return to Hawaiki, and told his slave Powhetengu to stay and look after this island. The slave, terrified of the people of this land, did not agree to this. When he left, Kupe threw his belt into the sea, to make it rough and prevent the slave from following him. Powhetengu made a canoe and tried to follow, but the rough seas overturned it and it turned into a rock in Aotea Harbour. Kupe sailed to Hawaiki, announcing that he had found a large land, and that its people were like ‘goblins’.

Whanganui-Taranaki

Whanganui-Taranaki traditions can be summarised as: Kupe came looking for his wife who had been abducted by (H)oturapa. His canoe was named Mataho(u)rua; Kupe was associated with Turi as his contemporary. Kupe cut up the land, and he was a brother of Ngake. Kupe encountered rough seas on his journey. The octopus story is known, but the creature is not named. Except in later versions which are somewhat suspect as to their authenticity, the accounts do not include the episode in which Kupe chases the octopus from Hawaiki (Simmons 1976:27). Here are some of the accounts from this area:

- A tradition written by Te Hukahuka on 25 October 1847 states that Kupe found no people on this island when he came. He returned and met Turi, and told him that all he had seen was 'a flock of spirits' (apu aparoa), and two birds: a fantail and a kōkako. Turi said let us go back there and Kupe said 'Kupe returns' and returned to Hawaiki.[20]

- In a tradition collected from Wiremu Tīpene Pōkaiatua of Manawapou in 1854 (Simmons 1976:23–24),[21] Kupe arrived at Wellington Harbour aboard the Mata’orua (Matahourua), looking for his wife Kuramarotini who had been abducted by his younger brother ‘Oturapa (Hoturapa). He could not find him, and returned, erecting a post at Pātea as a token of his visit. Kupe brought the karaka tree,[22] and also divided off the North Island, which had been attached to Hawaiki until then.

- In a legend from a manuscript by Piri Kawau of Āti Awa and dated approximately 1854 (Simmons 1976:24)[23] the canoe Matahorua (Matahourua) is the canoe that sailed ‘the great distance’ and was commanded by Reti. Kupe killed Hoturapa and took his wife Kuramarotini. Then they came to New Zealand.[24] Kupe cut up the land, and saw two inhabitants, Kōkako and Tiwaiwaka (Blue-wattled crow and Fantail). Then he returned to Hawaiki, and gave Turi directions for sailing to New Zealand.

- A Whanganui chief Hoani Wiremu Hipango gave a version to Rev. Richard Taylor in 1859 (Simmons 1976:24).[25] In this version, when Kupe came to New Zealand he found the land flowing. He made it lie quietly, and when Turi arrived, he found it floating.

- In October 1882 Rerete Tapo of Parikino said "Now listen, the first to come to this island was Kupe to fold and separate the great fish of Māui" (Simmons 1976:24).[26]

Rangitāne

- An 1893 account by Te Whetu of Ngāti Raukawa, who was familiar with Rangitāne traditions,[27] tells of Kupe with his daughters and two birds, Rupe (pigeon) and Kawauatoru (cormorant or shag), exploring the west coast of the North Island. Kupe sends the cormorant to rest the current in the Manukau harbour, which the bird reports as weak, and in Cook Strait, which the bird reports as too strong. The pigeon is sent to explore the interior of the island, and encounters a fantail and a crow (kōkako). Kupe stays at Wellington harbour and names two islands Matiu and Makoro after his daughters. On his return journey, Kupe meets Turi at an island and tells him of this island. At Hawaiki. Kupe recounts his adventures (Simmons 1976:26–27).[28]

South Island

The few references to Kupe in South Island sources indicate that the traditions are substantially the same as those of Ngāti Kahungunu, with whom Ngāi Tahu, the main tribe of the South Island, had strong genealogical and trading links (Simmons 1976:34).

- In one tradition Tamatea of the Tākitimu canoe, having been deserted by his three wives, sails around New Zealand looking for them, and shares with Kupe the honour of naming parts of the land.[29]

- White records a legend in which the Rangitāne chief Te Hau has his cultivations at Te Karaka ruined by Kupe who pours salt over them.[30]

Unlocated

"When Kupe, the first discoverer of New Zealand,first came in sight of the land,his wife cried,'He ao! He ao!" (a cloud! a cloud!). Great Barrier Island was therefore named Aotea (white cloud), and the long mainland Aotearoa (long white cloud). When Kupe finally returned to his homeland his people asked him why he did not call the newly discovered country after his fatherland. He replied, 'I preferred the warm breast to the cold one, the new land to the old land long forsaken'." [31]

Kupe Statue

William Trethewey produced the statuary for the New Zealand Centennial Exhibition that was held in 1939/40 in Rongotai, Wellington. A 100 feet (30 m) frieze depicted the progress of New Zealand, groupings of pioneers, lions in Art Deco style, a large fountain and a figure of Kupe standing on the prow of his canoe were produced for the centennial exhibition. Of all these works, only the Kupe Statue still remains.[32] After having spent many decades at Wellington Railway Station, then the Wellington Show and Sports Centre and finally at Te Papa, the Kupe Group Trust successfully fundraised to have the plaster statue cast in bronze. Since 2000, the bronze statue has been installed at the Wellington Waterfront.[33]

Notes

- ↑ Photograph of Stephenson Percy Smith by kind permission of the Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand, reference number 1/2-004600-F.

- ↑ whaikōrero: formal speech, oratory

- ↑ waiata: song, sung poem

- ↑ Simmons cites Catherin Servant, ‘Notice sur les Maoris de la Nouvelle Zélande’, 1842. Microfilm. (DU:Ho), from an original in the Marist Archives, Rome. Servant was stationed at Hokianga from 1838 to 1839 and then at Kororāreka (Russell) until 1842.

- ↑ In this version it is not made clear who Tuputupuwhenua was.

- ↑ The genealogy is: Kupe begot Matiu who begot Makoro who begot Maea who begot Mahu (or Maahu) who begot Nukutawhiti.

- ↑ Simmons cites A. Taonui, manuscript in Auckland Museum Library, Graham Collection, no. 120:2. Note also that Kupe and his great-great-great-grandchild appear to be contemporaries in this legend.

- 1 2 Simmons cites Shortland MS86, Hocken Library, Dunedin.

- ↑ That is, a striking natural feature which is said to be Kupe's bailer turned to stone.

- ↑ Simmons cites Kamira Manuscript Book No. 9, p. 259, but gives no date.

- ↑ The names translate as Kupe Earth, Kupe Sky, and Kupe Heart.

- ↑ The names of the nine others translate as echoing cliff, birds, spirit folk, insects, lizards and reptiles.

- ↑ That is, he left these items and they turned to stone.

- ↑ A later manuscript from the same area was published in the Journal of the Polynesian Society (Biggs 1957). This version contains episodes which appear to have been borrowed from literary sources, including associations with Toto, Rongorongo, Kuramarotini, Turi, and Hoturapa.

- ↑ Other Ngāti Kahungunu traditions, very similar to this, are given in a manuscript translated in Transactions of the New Zealand Institute, volume 15:448, in which Kupe appears as a name among the 13 children of Tato; also in John White, Ancient History of the Maori, 1887–1891, Volume 3:71–73; and in another account by White entitled Ahuriri Natives' Account of Hawaiki 1855, Turnbull Library Manuscript 94.

- ↑ Simmons cites Rev. J. Hamlin, ‘On the Mythology of New Zealanders’ Tasmanian Journal of Natural Science, 1842, I:260.

- ↑ Simmons cites Rev. W.R. Wade, A Journey in the Northern Island of New Zealand (George Rolwegan: Hobart) 1842:90.

- ↑ Simmons cites G. Graham (translator), Fragments of Ancient Maori History by Wirihana Aoterangi (Champtaloup and Edmiston: Auckland), 1923.

- ↑ 'Goblins' and 'fairies' represent an attempt by the original translators to render the names of various spiritual or quasi-spiritual beings given the lack of appropriate terms in English. Polynesian 'goblins' and 'fairies' tend to be much scarier entities than English ones.

- ↑ Simmons tentatively assigns this tradition to the Whanganui area and cites Grey New Zealand Māori Manuscript 102:35.

- ↑ Simmons cites Rev. R. Taylor, Te Ika a Maui (Wertheim and MacIntosh: London), 1855.

- ↑ Corynocarpus laevigatus, an important food tree which is endemic to New Zealand and thus not found elsewhere.

- ↑ Simmons cites G. Grey, Nga Mahi a Nga Tupuna. Polynesian Mythology (H. Brett: Auckland), 1885:19.

- ↑ At this point in the story, Grey inserts the story of the killing of the octopus Te Wheke-a-Muturangi. However, according to Simmons, this episode is not in Piri Kawau’s manuscript, and Grey’s source for it remains to be discovered.

- ↑ Simmons cites R. Taylor, ‘notes on New Zealand and its native inhabitants’, No. 6, p 110, MS, Auckland City Library.

- ↑ Simmons cites John White, MS 119, 'Miscellaneous material in Maori'.

- ↑ The Rangitāne people live on both sides of Cook Strait.

- ↑ Simmons cites Journal of the Polynesian Society, 1893, pp. 147–151.

- ↑ Simmons cites Rev, J.W. Stack, 'Remarks on Mr McKenzies Cameron's Theory respecting Kahui Tipua', Transactions of the New Zealand Institute 12, 1879:160

- ↑ Simmons cites White 1887–1891, III:199.

- ↑ Lilliput Maori Place Names. pub. A . H. Reed 1962 printed in Germany by Langenscheidt KG p36.,

- ↑ Phillips, Jock. "William Thomas Trethewey". Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 24 May 2011.

- ↑ "Art and Design". Wellington Waterfront. Retrieved 28 May 2011.

References

- B.G. Biggs, ‘Kupe, Na Himiona Kaamira, o Te Rarawa’ Journal of the Polynesian Society, 66, (1957), 217–248.

- R.D. Craig, Dictionary of Polynesian Mythology (Greenwood Press: New York, 1989).

- D.R. Simmons, The Great New Zealand Myth: a study of the discovery and origin traditions of the Maori (Reed: Wellington) 1976.

- D.R. Simmons, 'The Great New Zealand Myth' Art New Zealand No.4 (February–March 1977). URL: www.art-newzealand.com/Issues1to40/myth.htm, accessed 11 May 2006.

- J. White, The Ancient History of the Maori, 6 Volumes (Government Printer: Wellington), 1887–1891.

External links

- pvs-hawaii.com/stories/kupe.htm (the orthodox version)

- D.R Simmons 'The Great New Zealand Myth' Art New Zealand No.4 (February–March 1977) (article by Simmons about his book of the same name)

- "Kupe" – article in Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand

- "When was New Zealand first settled?" – ibid

- Te Whetu, "Te Haerenga Mai O Kupe I Hawaiki: The Coming of Kupe From Hawaiki To New Zealand", Journal of the Polynesian Society, September 1893, pp. 147–151

- Kupe Sites: A Photographic Journey – slideshow on the Te Papa Channel