Lachine massacre

| Lachine massacre | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of King William's War, Iroquois Wars | |||||||

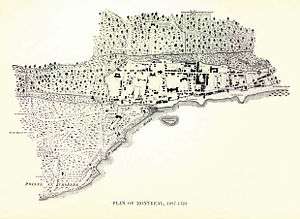

Map of Montreal, 1687 to 1723. The Lachine settlement was located southwest of Montreal proper. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| English-allied Mohawk Nation | New France | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 1,500 warriors | 375, mostly civilians | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 3 Mohawk killed | 72 French settlers killed | ||||||

The Lachine massacre, part of the Beaver Wars, occurred when 1,500 Mohawk warriors attacked by surprise the small, 375-inhabitant, settlement of Lachine, New France at the lower end of Montreal Island on the morning of August 5, 1689. The attack was precipitated by growing Iroquois dissatisfaction with the increased French incursions into their territory, and was encouraged by the settlers of New England as a way to leverage power against New France during King William's War.

In their attack, the Mohawk destroyed a substantial portion of the Lachine settlement by fire and killed or captured numerous inhabitants, although historic sources have varied widely in estimates of the number killed, from 24 to 250.

Background and motivations

The Mohawk and other Iroquois attacked the French and their native allies for a variety of reasons, related to both economic and cultural circumstances.

Cultural motives

The Europeans (French, Dutch and English) in the Northeast developed a fur trade with natives, including the Five Nations of the Iroquois; beaver furs were most desired. However, in the 17th century, the dominance of what historian Daniel Richter refers to as “Francophiles” or French takeover, contributed to an erosion of French-native relations. The French mission to assimilate natives required the abandonment of native tradition, which was met with resistance.[1] By 1667, large numbers of Huron and Iroquois, especially Mohawk, started arriving at the St Lawrence Valley and its mission villages, to escape the effects of warfare. Many traditionalists, including some Mohawk, resented the Jesuits for destroying traditional native society but were unable to do anything to stop them. However, traditionalists reluctantly accepted the establishment of a mission in order to have good relations with the French, whom they needed for trade.[2] This cultural invasion increased tensions between the two factions. The relationship between the French and the Iroquois were strained long before the Lachine Massacre, as the French maintained relations with other tribes as well, both for trade and war alliances, such as the Abenaki.[3] In 1679, following the end of the Iroquois war with the Susquehannock and the Mahican, the Iroquois raided native villages in the West. Pushing out Siouan tribes to the west, they claimed hunting grounds in the Ohio Valley by right of conquest. These were kept empty of inhabitants in order to encourage hunting. As a result, the Iroquois regularly raided trading parties in the western frontier which under French protection, and took loot from them. Following military confrontation in 1684, though the Iroquois negotiated a peace treaty with New France governor Le Febvre de la Barre, the treaty stated the Iroquois were free to attack the western Indians.[4] The French Crown objected to the treaty, and replaced LaBarre with the Marquis de Denonville. He was less sympathetic to native relations, and did not pay attention to the Iroquois-Algonquian tensions. In part, the Iroquois attacked the French because they were not willing to accept constraints against their warfare related to traditional Iroquois enemies.

What were known as "mourning wars" were also an important cultural factor in native warfare. Natives fought war to “avenge perceived wrongs committed by one people against another”.[5] These mourning wars were also a means to replace the dead within a native community. In times of war, natives would capture members of another native group and adopt them in order to rebuild their society. When new diseases such as smallpox killed large numbers of native people within their communities, survivors were motivated to warfare in order to take captives to rebuild.[6]

Economic motives

What the Iroquois wanted was not war, but instead a better share of the fur trade.[7] To serve as punishment for attacks on French fur fleets, New France ordered two expeditions under Courcelles and Tracy into Mohawk territory in 1666. These expeditions burned villages and destroyed much of the Mohawk winter corn supply. In addition, Denonville’s 1687 invasion of the Seneca nation country destroyed approximately 1,200,000 bushels of corn, crippling the Iroquois economy.[8] This kind of aggression served as fuel for the Iroquois’ retaliation that was to come.

Following two decades of uneasy peace, Britain and France declared war against one another in 1689. Despite the 1669 Treaty of Whitehall, in which European forces agreed that Continental conflicts would not disrupt colonial peace and neutrality,[9] the war was fought primarily by proxy in New France and New England. The British of New York prompted local Iroquois warriors to attack New France's undefended settlements.[10][11][12] While the British were preparing to engage in acts of warfare, the inhabitants of New France were ill prepared to defend against the Indian attacks” due to the isolation of the farms and villages. Denonville was quoted as saying “If we have a war, nothing can save the country but a miracle of God,”.[13]

The attack

On the rainy morning of August 5, 1689, Iroquois warriors used surprise to launch their nighttime raid against the undefended settlement of Lachine. They traveled up the Saint Lawrence River by boat, crossed Lake Saint-Louis, and landed on the south shore of Montreal Island. While the colonists slept, the invaders surrounded their homes and waited for their leader to signal when the attack should begin.[11] They attacked the homes, breaking down doors and windows, and dragging the colonists outside, where many were killed.[11] When some of the colonists barricaded themselves within the village's structures, the attackers set fire to the buildings and waited for the settlers to flee the flames.[11][12] According to a 1992 article, the Iroquois, wielding weapons such as the tomahawk, killed 24 French and took more than 70 prisoners.[14][15] Other sources, such as Encyclopædia Britannica, claim that 250 settlers and soldiers lost their lives during the “Massacre.”[16] The Iroquois wanted to avenge the 1,200,000 bushels of corn burned by the French, but since they were unable to reach the food stores in Montreal, they kidnapped and killed the Lachine crop producers instead.[17] Lachine was the main departure point for westward-traveling fur traders, which may have provided extra motivation for the Mohawk attack.[18]

Aftermath

Word of the attack spread when one of the Lachine survivors reached a local garrison, three miles (4.8 km) away, and notified the soldiers of the events.[20] In response to the attack, the French mobilized 200 soldiers, under the command of Daniel d'Auger de Subercase, along with 100 armed civilians and some soldiers from nearby forts Rémy, Rolland and La Présentation, to marched against the Iroquois.[20] They defended some of the fleeing colonists from their Mohawk pursuers, but just prior to reaching Lachine, the armed forces were recalled to Fort Rolland by order of Governor Denonville. He was trying to pacify the local Iroquois inhabitants.[21] Governor Denonville had 700 soldiers at his disposal within the Montreal barracks, and might have overtaken the Iroquois forces. He decided to follow a diplomatic route.[12]

Numerous attacks from both sides followed, but none were fatal, and the two groups quickly realized the futility of their attempts to drive the other out. In February 1690, the French began peace negotiations with the Iroquois. The French returned captured natives in exchange for the beginnings of peace talks.[22] Through the 1690s, there were no major French or native raids and, even against the will of the English, peace talks continued.[23] This time of relative peace eventually led to the Montreal Treaty of 1701, by which the Iroquois promised to remain neutral in case of war between the French and English.[24]

Following the events at Lachine, Denonville was recalled to France for matters unrelated to the massacre,[25][26] and Louis de Buade de Frontenac took over governorship of Montreal in October 1689.[27] Frontenac launched raids of vengeance against the English colonists to the south "in Canadien style" by attacking during the winter months of 1690, including the Schenectady massacre.[12][28][29][30]

Potential Bias

Francis Parkman, an American historian who was one of the first to write about natives within the colonial historical narrative, argues that the Iroquois wars “were products of an ‘insensate fury’ and ‘mad ambition’".[31] He said that the Iroquois waged wars due to the extinction of the beaver, their growing dependence on European goods, and resentment at the extermination of native culture. Parkman argues that the Iroquois had become so dependent on European goods that they needed these items in order to survive. In his research, Parkman had no evidence to support his claims. He assumed that the natives’ culture was inferior to the British-American, and overlooked potential reasons for the Iroquois attacks. Parkman’s interpretation neglected to explain why the Iroquois had waged war against other native groups as well. Parkman’s view would later on be dismissed due to its ethnocentric interpretation of the events.

Jose Brandao, a historian specializing in North American Native history, suggests that contemporary analyses of the Lachine Massacre continue to demonstrate cultural bias. Brandao criticizes historians Parkman, Charles McIlwain, and George Hunt for citing the growing dependence on European goods (which were, according to these historians, viewed by the Iroquois as superior to other goods) as a reason for Iroquois dissatisfaction and violence. Brando dismisses this theory as a largely ethnocentric interpretation with little evidence to support it.[32] Brandao also dismisses Hunt’s suggestion that natives, similar to the Europeans, waged wars for economic reasons.

Historical accounts

According to historian Jean-Francois Lozier, the factors influencing the course of war and peace throughout the region of New-France were not exclusive to the relations between the French and Iroquois, or those between the French and British crowns.[33] A number of factors provide context for the Lachine Massacre.

Sources of information regarding victims of the Iroquois in New France are the writings of Jesuit priests; the state registry of parishes in Quebec, Trois-Rivieres, and Montreal; letters written by Marie Guyart (French: Mère Marie de l’Incarnation); and the writings of Samuel Champlain. However, the accuracy of these sources and reports vary.[34] For instance, in the town of Trois-Rivieres, approximately one third of deaths attributed to the Iroquois are missing names.[35] According to Canadian historian John A. Dickinson, although the cruelty of the Iroquois was real, their threat was neither as constant nor terrible as the sources of the time represented, but they were feeling under siege.[36]

European accounts of the Lachine massacre come from two primary sources, survivors of the attack, and Catholic missionaries in the area.

Initial reports inflated the Lachine death toll significantly. Colby arrived at the total number of dead, 24, by examining Catholic parish registers before and after the attack.[37] French Catholic accounts of the attack were recorded. François Vachon de Belmont, the fifth superior of the Sulpicians of Montreal, wrote in his History of Canada:

After this total victory, the unhappy band of prisoners was subjected to all the rage which the cruellest vengeance could inspire in these savages. They were taken to the far side of Lake St. Louis by the victorious army, which shouted ninety times while crossing to indicate the number of prisoners or scalps they had taken, saying, we have been tricked, Ononthio, we will trick you as well. Once they had landed, they lit fires, planted stakes in the ground, burned five Frenchmen, roasted six children, and grilled some others on the coals and ate them.[10]

Surviving prisoners of the Lachine massacre reported that 48 of their colleagues were tortured, burned and eaten shortly after being taken captive.[12] Further, many survivors showed evidence of ritual torture and recounted their experiences.[12] Following the attack, the French colonists retrieved many English-made weapons which the Mohawk had left behind in their retreat from the island. The evidence of English arming the Mohawk incited a long-standing hatred of the English colonists of New York and demands for revenge.[12] Iroquois accounts of the attack have not been recovered, as they were recounted in oral histories. French sources reported that only three of the attackers were killed.[11] Because all written accounts of the attack were by the French victims, their reports of cannibalism and parents being forced to throw their children onto burning fires may be exaggerated or apocryphal. At the same time, the Mohawk and Iroquois used ritual torture after warfare, sometimes to honor the bravery of enemy warriors. It was common practice among native tribes at the time.[11]

See also

Citations

- ↑ Richter, Daniel (1992). Ordeal of the Longhouse. University of North Carolina Press. pp. 105–109.

- ↑ Richter, Daniel (1992). The Ordeal of the Longhouse. University of North Carolina Press.

- ↑ Lyons, Chuck (2007). 36 "France's Fateful Strike Against the Iroquois" Check

|url=value (help). Quarterly Journal of Military History: 34–44. - ↑ Lyons, Chuck (2007). 36 "France's Fateful Strike Against the Iroquois" Check

|url=value (help). The Quarterly Journal of Military History: 37. - ↑ Rushford, Brett (2012). The Bonds of Alliance: Indigenous Slaves in New France. University of North Carolina Press. p. 4.

- ↑ Rushford, Brett (2012). The Bonds of Alliance: Indigenous Slaves in New France. University of North Carolina Press. p. 29.

- ↑ Wallace, Paul A. W. (1956). "The Iroquois: A Brief Outline of their History". Pennsylvania History: 25.

- ↑ Wallace, Paul A. W. (1956). "The Iroquois: A Brief Outline of Their History". Pennsylvania History: 24.

- ↑ Daugherty, J.E. (January 1983). "The Colonial Struggle for Acadia, The Initial Phase: 1686–1713". Maritime Indian Treaties In Historical Perspective. Department of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada, Government of Canada. Retrieved 2007-12-01.

- 1 2 "The Lachine massacre". Claiming the Wilderness: New France's Expansion. CBC. Retrieved 2007-11-21.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Borthwick, p. 10

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Ledoux, Denis. "The Lachine Massacre, 1689". Here to Stay. The Memoir Network. Retrieved 2013-10-18.

- ↑ Lyons, Chuck (2007). 36. "France's Fateful Strike Against the Iroquois" Check

|url=value (help). The Quarterly Journal of Military History: 19. - ↑ Richter, Daniel (1992). The Ordeal of the Longhouse. University of North Carolina Press. pp. 150–165.

- ↑ Taylor, Colin (2007). "Native American Weapons". Material Culture. 39: 82–84. JSTOR 29764420.

- ↑ Encyclopedia Britannica Online "Lachine:. 2013.

- ↑ Wallace, Paul A. W. (1956). "The Iroquois: A Brief Outline of Their History". Pennsylvania History: 24–25.

- ↑ Encyclopedia Britannica Online "Lachine". 2013.

- ↑ "Militarizing New France". Canadian Military Heritage. Government of Canada. June 20, 2004. Archived from the original on May 5, 2007. Retrieved 2007-11-25.

- 1 2 Winsor, p. 351

- ↑ George, pp. 93–94

- ↑ Richter, Daniel (2007). The Ordeal of the Longhouse. University of North Carolina Press. pp. 165–166.

- ↑ Richter, Daniel (2007). The Ordeal of the Longhouse. Williamsburg: University of North Carolina Press. p. 170.

- ↑ Wallace, Paul A. W. (1956). "The Iroquois: A Brief Outline of Their History". Pennsylvania History: 26.

- ↑ Campbell, p. 55

- ↑ Colby, p. 115

- ↑ Colby, p. 112

- ↑ Campbell, p. 117

- ↑ "1690: A Key Year". Canadian Military Heritage. Government of Canada. June 20, 2004. Retrieved 2007-11-30.

- ↑ Colby, p. 116

- ↑ Brandao, jose (200). Your Fyre Shall Burn No More. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. p. 8.

- ↑ Brandao, jose (200). Your Fyre Shall Burn No More. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. p. 9.

- ↑ Lozier, Jean-Francois (2012). In Each Other's Arms: France and the St Lawrence Mission Villages in War and Peace, 1630-1730. University of Toronto Press.

- ↑ Dickinson, John (1982). "La guerre iroquoise et la mortalité en Nouvelle- France, 1608 -1666". Revue d'histoire de L'Amérique française: 54, 32.

- ↑ Dickinson, John (1982). "La guerre iroquoise et la mortalité en Nouvelle- France, 1608 -1666". Revue d'histoire de L'Amérique française: 34.

- ↑ Dickinson, John (1982). "La guerre iroquoise et la mortalité en Nouvelle- France, 1608 -1666". Revue d'histoire de L'Amérique française: 47.

- ↑ Colby, p. 111

References

- Borthwick, John Douglas (1892). History and Biographical Gazetteer of Montreal to the Year 1892. Montreal: John Lovell (no copyright in the United States).

- Campbell, Thomas Joseph (1916). Pioneer Laymen of North America. Boston: The America Press (No copyright in the United States).

- Colby, Charles William (1915). The Fighting Governor: A Chronicle of Frontenac. New York: Glasgow, Brook & Company (No copyright in the United States).

- George, Charles; Douglas Roberts (1897). A History of Canada. Boston: The Page Company (no copyright in the United States).

- Winsor, Justin (1884). Narrative and Critical History of America. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Company (no copyright in the United States).

Coordinates: 45°25′54″N 73°40′30″W / 45.431667°N 73.675°W