Larino

| Larino | ||

|---|---|---|

| Comune | ||

| Comune di Larino | ||

|

Detail of the Cathedral's portal. | ||

| ||

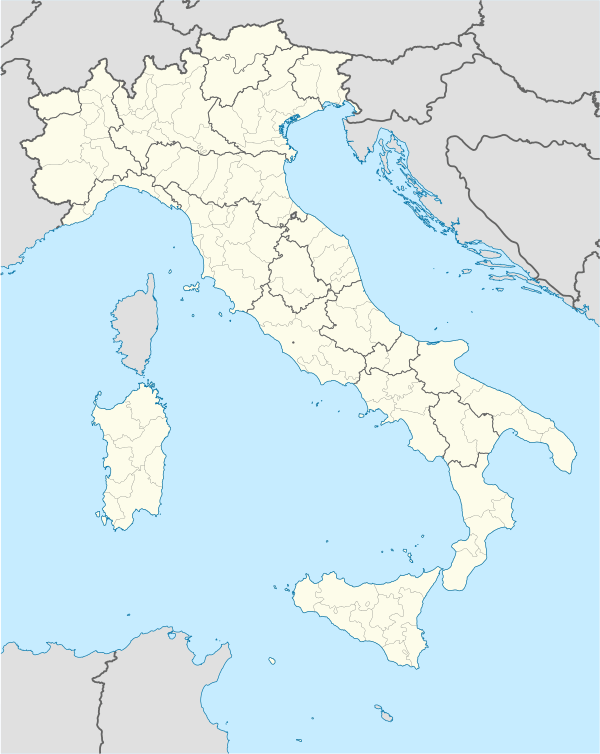

Larino Location of Larino in Italy | ||

| Coordinates: 41°48′N 14°55′E / 41.800°N 14.917°E | ||

| Country | Italy | |

| Region | Molise | |

| Province / Metropolitan city | Campobasso (CB) | |

| Government | ||

| • Mayor | Vincenzo Notarangelo | |

| Area | ||

| • Total | 88 km2 (34 sq mi) | |

| Elevation | 341 m (1,119 ft) | |

| Population (30 September 2012)[1] | ||

| • Total | 7,087 | |

| • Density | 81/km2 (210/sq mi) | |

| Demonym(s) | Larinesi | |

| Time zone | CET (UTC+1) | |

| • Summer (DST) | CEST (UTC+2) | |

| Postal code | 86035 | |

| Dialing code | 0874 | |

| Patron saint | San Pardo and San Primiano | |

| Saint day | May 26 | |

| Website | Official website | |

Larino (Latin: Larinum, Campobassan dialect: Larìne) is a town and comune of approximately 8,100 inhabitants in Molise, province of Campobasso, southern Italy. It is located in the fertile valley of the Biferno River.

The old town, seen from the mountains, is shaped like a bird's wing. The new town, called Piano San Leonardo, is built on a mountainside.

History

The city of Larino has been continuously inhabited for millennia. Originally settled by the Samnite and Frentani tribes of Southern Italy, the city came under the control of the Oscan civilization. In 217 BC, the Romans defeated Hannibal here, and it was later incorporated into the Roman Empire, where it was classified as a municipium, and added to the Secunda Regio (Apulia).

When Julius Caesar and Pompey the Great fought for the power in Rome, the latter is said to have joined two of his legions who were encamped at Larinum. Earlier the consul Claudius marched through Larinum on his way to attack the Carthaginian Hasdrubal. The city's name appears in the works of the ancient historians Livy and Pliny. An important senatus consultum restricting public performances by members of the Roman upper classes was found nearby.[2]

The modern city was built in the 14th century, after the old one, about 1.5 km away, was destroyed in an earthquake after having repeatedly been sacked by the Saracens. The old Roman city of Larinum was situated along the main road to the South-East, which started on the coast in Histonium (Vasto), and ran from Larinum eastward to Sipontum. The main road also branched off at Larinum into a secondary road to Bovianum Vetus.

In 1656, a plague nearly wiped out the city. The 373 survivors were prepared to abandon the settlement, but through the vigorous efforts of then Bishop Giuseppe Catalano, they were convinced to stay, and the city grew and thrived once again.

During World War II the radio reported that Larino had been totally destroyed in a bombardment. While it was true that the Allies and the Germans were in the vicinity of the town, hostility was avoided and the town was preserved. The city faced a large exodus during the 1950–60s, due to the extreme poverty of the Molise region, and there is a large community of Larinesi living abroad, as well as their first- and second-generation descendants.

Main sights

Roman amphitheatre

The elliptical amphitheater was built in the 1st century AD by a prominent citizen of Larino who had made his fortune in far away Rome. The arena could comfortably seat 12,000 spectators. The structure was built into a natural declivity in the terrain.

Cathedral and Fontana Nuova

The Fontana Nuova ("New Fountain" or A fonte 'e Sam Parde, Saint Pardo's fountain), now in disrepair, and the Duomo (Cathedral), made a minor basilica in 1928 by Pius XI, which is considered by some to be one of the finest examples of Gothic architecture in Italy. It was built in the 10th and 11th centuries and inaugurated in 1319. It was restored and renovated many times, with the addition of a Gothic arch in 1451, a belltower in 1523 and interior renovations in the 18th century. It was likely built, in part, by architects and engineers brought in from the Angevine rulers of Naples. At that time there was a tradition of using "spoila", remnants of classical buildings, and it is likely that the structure used cut stone from the classical city which existed in the area of what is now called Piano San Leonardo. One of the church's main elements is the portal, with columns included in a blind protyrus, and examples of medieval decoration including lions, gryphons and a lunette with the Crucifixion; the portal is surmounted by a rose window in Gothic style sided by depictions of the Four Evangelists and the Agnus Dei. The Galuppi Tower (1312), across from the Cathedral, has been strengthened by large square metallic plates. The tower, which was part of the old town's defenses, was the bell tower of a now abandoned convent. The entire structure was built on the command of Pope Clement V at the very beginning of the 14th century.

Robert Gardner in his studies, noted an earlier, but less grand cathedral mirrored the design of the present gothic structure. The twin edifices were designed by Francesco Petrini at the beginning of the 14th century. These churches, like those at Lucera, Foggia, Manfredonia, Vasto, Ortona, for example, were built by the Angevin rulers in the "French style.[3]

Some features set the Cathedral in Larino apart. For one thing, it is likely built on the location of an earlier church dedicated to the Virgin Mary. For while it follows the structural guidelines common to many churches built at this time (around 1300) in Southern Italy, it is irregular and asymmetrical. The façade of the church is canted at an angle and the rows of internal columns do not match. There are fewer on one side of the structure than the other.

Recently, during work on the vaults in the Bishop’s Palace to the side of the Cathedral the vaulted ceilings were revealed. In some instances they are built of very regular Roman brick. In some other cases they are structured, in exactly the same manner, with rubble.

The cathedral in Larino is exceptional even in the sophistication of its structure and the consistency of the craftsmanship. The rather primitive wall paintings in the cathedral were a part of the approach to ecclesiastical decoration favoured by the French kings.

In Apulia external decoration was more elaborate than elsewhere featuring especially elaborate portals. This is true of Larino. According to scholars the decorative excellence of churches at Atri, L’Aquila, Penne, Larino, and Ortona were fashioned by local schools of craftsmen in some isolation from other influences. However the templates which were available were used over and over again without much evolution of the form. One explanation for this is that an "imported form", not natural to the culture of the new place in which it is implemented often becomes "frozen in time".

In the 1290s, not long before the construction of the Cathedral in Larino, there emerged a taste for "spolia". This desire to utilize antique (from Roman times) building materials and incorporate them in the building to the ecclesiastic structures became emphasized during the reign of Charles II between 1295 and 1309. Today in Larino you can see evidence of this usage of ancient materials in the base of the Galuppi bell tower across the square from the cathedral. It’s obvious that the stone was from a variety of sources. One block of material even has a deep round hole which suggests that it may have been taken from an ancient well, although local tradition holds that it was a place where orphan babies could be placed with some safety when they were abandoned by their mothers.

If an observer stands in the archway of the bell tower and looks upward you will see a series of parallel lines running up from the supporting massive cut stone base to the top of the arch. The lines were formed by the long ago disintegration of cane which was used to form the stone arch way. The cane would be bent in the desired shape (a gothic arch) and supported from beneath. Then the masons would place the rubble and mortar in shape. The first layer would be allowed to set and then the higher level would be installed, again built with a combination of rubble and cut stone placed at the edges of the structure. The Cathedral before the 1960s was covered in baroque ornamentation from much later periods.

Pictures exist of the Cathedral with an additional set of windows to the right and left of the great portal. If you look at the face of the wall you will notice newer rectangular stones placed where the windows once existed. To know if the windows were original to the design you would have to search out a template, possibly in Lanciano.

The bell tower of the Cathedral was built later and it too incorporates classical elements in its structure."

San Francesco

The Franciscan church is contemporary with the cathedral, but with a simpler and more restrained monastic taste. During recent restorations, primitive wall paintings were found behind the choir. Much of its later Baroque ornamentation has been removed with recent restorations. In the exposed side wall of the church, there are three bricked-in elongated windows. The wall itself is an odd combination of cut stone, brick, and rubble. At one time it was thought that the different materials may have been caused by repair to damage caused by an earthquake, but the truth is likely that the base was made of regular cut stone. Once above the level of the base any materials could be used because they were likely faced with a plaster much as many columns from Roman times were actually built with brick with a smooth coating of cement.

The Fleur De Lys appear on the columns at the portal because the Kings and Monks who supervised construction were French. The local workers were likely employed as common labourers. The cut stone was hauled by the horse and bull drawn carts from the classical city to the construction site. Roof tiles were made in "the French manner" and the walls were completely covered in frescoes. San Francesco was built almost devoid of stone ornamentation. The church we see today, like so many Italian churches, was forced later to adhere to a taste for Baroque with what many moderns see as "excessive decoration".

Other churches in the city include, Santo Stefano and Santa Maria della Pietà.

Palazzo Ducale (Ducal Palace)

Now the seat of municipal government, it was probably originally built as a Norman castle. The palace is now repainted as it was decades ago. The exterior walls are alternating panels of whitish grey and charcoal black. The upper levels, surrounding the stone windows are a combination of pink and cream. The top level, overlooking a large terrace, is faced in sunflower yellow. Later a part of the building became Albergo Moderno(Modern Hotel), is now abandoned. The structure has three distinct facades. One distinctly shows the physical structure of the original castle. The second has a renaissance feel and housed the rulers of the town. The third is a large brick neoclassical structure which was adjoined to the castle in the 19th century.

Culture

The city has many fairs and festivals, notably those of San Primiano and of San Pardo. These include parties and religious processions. Traditional recipes of the town include Pigna Larinese (pigna 'Arnese, a type of cake) and taralli con l'uova (i taralle cu ll'ove, egg taralli). It also has its own cultivar of olive, known as the Gentile di Larino, which is highly prized for its oil.

In the summer a series of festivals is held. May 25–27 of each year is dedicated to the Festival of San Pardo (A fest"e Sam Parde). In 2005, there were over 110 carts festooned with hand-made flowers. Each wagon is pulled by two white oxen. A procession moves from the historic centre and the cathedral to the cemetery and the old church which dates from the earliest days of the Christian era. It is at once a religious event, a historic event, and a family celebration. Each cart belongs to a particular family, and the cart's position in the procession is a sign of social standing.

Twin towns

San Pellegrino Terme, Italy

San Pellegrino Terme, Italy

Transportation

Larino is served by a railway station on the Termoli–Venafro line.

Important people

- Antonio De Santis, Italian poet

- Angelo Vetta, member of Serbian Learned Society (Српско учено друштво) from 1885, honorary member of Serbian Royal Academy (Српска краљевска академија) from 1892.[4]

References

- ↑ Population data from Istat

- ↑ Levick, Barbara (24 September 2012). "The Senatus Consultum from Larinum". Journal of Roman Studies. 73: 97–115. doi:10.2307/300074. JSTOR 300074.

- ↑ Robert Gardner, Larino: The Miracle of the Molise.

- ↑ Angelo Vetta on SANU web site

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Larino. |

- Official website

- Festival of San Pardo photo gallery

- Larino The Miracle of the Molise

- URP Larino

- metroLArino

- Dr. Robert Gardner Photostream: Larino

- A Virtual Tour of Larino's Cathedral

- One of Molise's Most Beautiful Cathedral Portals