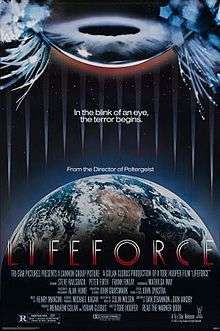

Lifeforce (film)

| Lifeforce | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Tobe Hooper |

| Produced by |

Yoram Globus Menahem Golan |

| Screenplay by |

Dan O'Bannon Don Jakoby |

| Based on |

The Space Vampires by Colin Wilson |

| Starring | |

| Music by | Henry Mancini |

| Cinematography | Alan Hume |

| Edited by | John Grover |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | TriStar Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 116 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $25 million[1] |

| Box office | $11.6 million (domestic) |

Lifeforce is a 1985 science fiction horror film directed by Tobe Hooper and written by Dan O'Bannon and Don Jakoby, based on Colin Wilson's 1976 novel, The Space Vampires. Featuring Steve Railsback, Peter Firth, Frank Finlay, Mathilda May, and Patrick Stewart, the film portrays the events that unfold "after a trio of humanoids in a state of suspended animation are brought to earth after being discovered in the hold of an abandoned European space shuttle."[2] The film received mixed to positive reviews, but was a box office bomb, failing to recoup its budget.

Plot

The crew of the space shuttle Churchill finds a 150-mile long spaceship hidden in the corona of Halley's Comet. The crew finds hundreds of dead, shrivelled bat-like creatures and three naked humanoid bodies (two male and one female) in suspended animation within glass containers. The crew recovers the three aliens and begins the return trip to Earth.

During the return journey, mission control loses contact with the shuttle and a rescue mission is launched to investigate. The rescuers discover that the Churchill has been severely damaged by fire, with its internal components destroyed, and the three containers bearing the aliens are all that remain intact. The aliens are taken to the European Space Research Centre in London where they are watched over by Dr. Leonard Bukovski (Gothard) and Dr. Hans Fallada (Finlay). Prior to an autopsy, the female alien (May) awakens and drains the "life force" out of a guard. The female alien then escapes the research facility and proceeds to drain various other humans of their life force, revealing an ability to shape-shift. It transpires that the aliens are from a race of space vampires that consume the life force of living beings, rather than their blood.

Meanwhile, in Texas, an escape pod from the Churchill is found, with Colonel Tom Carlsen (Railsback) inside. Carlsen is flown to London where he describes the course of events, culminating in the draining of the crew's life force. Carlsen explains that he set fire to the shuttle with the intention of saving Earth from the same fate and escaped in the pod. However, when he is hypnotized, it becomes clear that Carlsen possesses a psychic link to the female alien. Carlsen and SAS Col. Colin Caine (Firth) trace the alien to a psychiatric hospital in Yorkshire. While in Yorkshire, the two believe they have managed to trap the alien within the heavily sedated body of the hospital's manager, Dr Armstrong (Stewart); but Carlsen and Caine later learn that they were deceived, as the aliens had wanted to draw the pair out of London.

As Carlsen and Caine are transporting Dr Armstrong in a helicopter back to London, the alien girl breaks free from her sedated host and disappears. When they reach London a "plague" has overtaken the city and martial law has been declared. The two male vampires, previously thought destroyed, have escaped from confinement by shape-shifting into the soldiers guarding them; the pair then transform most of London's population into zombies. After their life force has been drained by the male vampires, the victims seek out other humans in order to absorb their life force, perpetuating the cycle. The absorbed life forces are channeled by the male vampires to the female vampire, who transmits the accumulated energy to their spaceship in Earth's orbit.

Fallada impales one of the male vampires with an ancient device of "leaded iron". Carlsen admits to Caine that, while on the shuttle, he felt compelled to open the female vampire's container and to share his life force with her. She is later found inside St. Paul's Cathedral, lying upon the altar, transferring the energy to her spaceship. She reveals, much to Carlsen's shock, that they are a part of each other due to the sharing of their life forces, thus their psychic bond.

Caine follows Carlsen into the cathedral and is intercepted by the second male vampire, whom he dispatches. Carlsen impales himself and the female alien simultaneously. The female vampire is only wounded and returns to her ship with Carlsen in tow, releasing a burst of energy that blows open the cupola dome of St. Paul's. The two ascend the column of energy to the spaceship, which then returns to its hiding place within the comet.

Cast

- Steve Railsback as Col. Tom Carlsen

- Peter Firth as Col. Colin Caine

- Frank Finlay as Dr. Hans Fallada

- Mathilda May as Space Girl

- Patrick Stewart as Dr. Armstrong

- Michael Gothard as Dr. Leonard Bukovsky

- Nicholas Ball as Roger Derebridge

- Aubrey Morris as Sir Percy Heseltine

- Nancy Paul as Ellen Donaldson

- John Hallam as Lamson

- Sidney Kean as Brash Guard

- Chris Sullivan as Kelly

- Chris Jagger as First Vampire

- Bill Malin as Second Vampire

Production

Background

Lifeforce was the first film of Tobe Hooper's three-picture deal with Cannon Films, following his enormous success with Poltergeist in 1982, which was a collaboration with producer Steven Spielberg. The other two films are the remake of Invaders from Mars and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2.[3]

Filming began on February 2, 1984. Before Tobe Hooper was finally approved, Michael Winner, at one point, was offered the chance to direct the film.[4]

The movie was originally filmed and promoted under the same title as the Colin Wilson novel. Cannon Films, which reportedly spent nearly US$25 million in hopes of creating a blockbuster movie, disliked The Space Vampires for sounding too much like another of the studio's typical low budget exploitation films. As a result, the title was changed to Lifeforce, referring to the spiritual energy the space vampires drain from their victims, and it was edited for its US theatrical release by TriStar Pictures into a 101-minute domestic cut that was partially re-scored by Michael Kamen, with a majority of Henry Mancini's original music remaining.

Screenplay

The screenplay was written by Dan O'Bannon and Don Jakoby. Script doctors Michael Armstrong and Olaf Pooley did some uncredited work on the script. Tobe Hooper came up with the idea of using Halley's Comet in the screenplay, rather than the asteroid belt as originally used in the novel, as the comet was going to pass by Earth one year following the film's release. The time settings were also changed from the mid-21st century to the present day. .

Colin Wilson was unhappy with the way the film turned out. He wrote of it, "John Fowles had once told me that the film of The Magus was the worst movie ever made. After seeing Lifeforce I sent him a postcard telling him that I had gone one better."[5]

Special effects

The film marked the fourth project to feature special effects produced by Academy Award winner John Dykstra, who in 1986 was granted with the "Caixa Catalunya Award for Best Special Effects" in the Sitges Film Festival (located in Spain) for his special effects work in Lifeforce.[note 1] The umbrella-like alien spaceship was modelled after an artichoke, while the model London destroyed in the film was actually the remains of Tucktonia, a model village near Christchurch, United Kingdom, that had closed not long before the shooting of the film. It took a week to film the death scene of the pathologist played by Jerome Willis, and bodycasts of Frank Finlay, Patrick Stewart and Aubrey Morris were made by make-up effects supervisor Nick Maley for their death scenes.

One effect near the end of the film involving the column of energy rising from the female alien through the top of St. Paul's Cathedral to the spacecraft was engineered by art director Tony Reading. A column of 3-M material was placed against black velvet and a crew member blew cigar smoke into its bottom. This image was then front projected onto a translucent projection screen behind the actors to create the energy column.[6]

Music

James Horner was first asked to write the film score before Henry Mancini was brought in and produced a score consisting of 90 minutes of an occasionally atonal and ambient music using the London Symphony Orchestra.[7] Mancini had agreed to do the film based on the original concept of a 15-minute essentially dialogue-free opening sequence involving the discovery and exploration of the alien spacecraft and the moving of the three aliens back to the Churchill, for which he composed a tonal "space ballet."[7] As discussed below, this opening section was largely cut from the film.

For the US domestic cut version, Michael Kamen was approved to write the occasional alternative music cues that were partially re-scored and placed in at the last minute for some of the US domestic prints of the film.

Editing and post-production

The initial cut of Lifeforce as edited by Tobe Hooper was 128 mins long. This is 12 minutes longer than the final version which had several scenes cut, most of them taking place on the space shuttle Churchill. According to Nicholas Ball, who played the main British astronaut, Derebridge, it was felt that there was too much material in outer space and so the majority of the Churchill scenes were deleted. Also, most of Nicholas Ball's performance ended up on the cutting room floor according to an interview he gave on the UK talk show Wogan in 1985.

According to interviews with Bill Malin, who plays one of the male vampires, the film went over schedule during production. Because of this some important scenes were never shot, and the film was shut down at one time because the studio had simply run out of money.

Despite being credited on the US domestic cut, the following actors were deleted from that cut of the film: John Woodnutt, John Forbes-Robertson and Russell Sommers. The Churchill commanding officer Rawlins, played by Geoffrey Frederick, was British, but in post-production it was decided that Patrick Jordan would dub his voice. Also in the US version, some of Geoffrey Frederick's voiceover heard on the Churchill is dubbed.

The US domestic cut version

The film was edited for its US theatrical release by TriStar Pictures to a 101-minute domestic cut version that was partially re-scored by Michael Kamen, with a majority of Henry Mancini's original music still remaining. The original 116 minute international theatrical cut version, which is now currently available on video and DVD, contains more nudity and violent footage that Tri-Star cut from the domestic version, along with all of Mancini's score in place of Kamen's occasional music cues.

Reception

The movie received mixed reviews from critics.[8][9] Michael Wilmington in the New York Times said the movie was "such a peculiar movie that it's difficult to get a handle on it."[10] Jay Carr wrote in The Boston Globe that "it plays like a tap-dancing zombie."[11] John Clute dismissed Lifeforce as a "deeply silly flick".[12] Leonard Maltin called the film "completely crazy," and said it was "ridiculous, but so bizarre, it's fascinating."[13]

As of April 23, 2014, it holds a 67% "Fresh" score on Rotten Tomatoes.

Box office

Lifeforce was released on June 21, 1985 to negative box office returns.[8] The film opened in fourth place, losing a head-to-head battle against Ron Howard's sci-fi film, Cocoon. The film earned $11,603,545 at the US box office.[14]

Home media

The first release on video in the UK was the heavily cut US 'Domestic cut'. The full 'International cut' was not available until it was released by MGM in 2000s. The U.S. saw the first release of the 'International cut' with MGM/UA's 1994 release of the Deluxe Widescreen Letterbox laserdisc.

Scream Factory announced they would be releasing Lifeforce on Blu-ray/DVD Combo Pack on June 18, 2013.[15] This release included the theatrical US version of the film as well as the International cut of the film.

Arrow Video released the movie as a Steelbook two-disc Blu-ray special edition in October, 2013 in the UK, with the same features as the US Blu-ray release.

See also

Notes

- ↑ This award (presented annually) is the Special Effects Award attributed by the Sitges Film Festival, but its name has changed among years, depending on different sponsors. In 1986 it was called "Premio Caixa Catalunya a los Mejores Efectos Especiales" ("Caixa Catalunya Award for Best Special Effects") since that year the sponsor was Caixa Catalunya, a local bank.

References

- ↑ "Disasters Outnumber Movie Hits". South Florida Sun-Sentinel. 1985-09-04. Retrieved 2012-06-05.

- ↑ "Lifeforce". Film Society of Lincoln Center. 2012. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ↑ Macor, Alison (2010). Chainsaws, Slackers, and Spy Kids. University of Texas Press. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-292-77829-0.

- ↑ "Lifeforce Fun Facts" Retrieved 3 June 2015

- ↑ Wilson, Colin (2011). Dreaming to Some Purpose. Random House. p. 332. ISBN 9781446473603.

- ↑ Rizzo, Michael (2005). The Art Direction Handbook for Film. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-240-80680-8.

- 1 2 Caps, John (2012). Henry Mancini: Reinventing Film Music. University of Illinois Press. pp. 193–98. ISBN 978-0-252-09384-5.

- 1 2 Deborah Caulfield (1985-08-10). "Hooper Targets Martians". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2012-06-05.

- ↑ Janet Maslin (1985-06-21). "The Screen: 'Lifeforce'". The New York Times. Retrieved 2012-06-05.

- ↑ Michael Wilmington (1985-06-22). "Movie Review: Fear in Forefront of Peculiar 'Lifeforce'". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2012-06-05.

- ↑ Jay Carr (1985-06-22). "'Lifeforce' Misses a Great Opportunity". Boston Globe. Retrieved 2012-06-09.

- ↑ John Clute,Science Fiction : The Illustrated Encyclopedia. New York : Dorling Kindersley. ISBN 0789401851 (p.285).

- ↑

- ↑ Lifeforce (1985) - Weekend Box Office Results

- ↑ Dee, Jake (2013-01-04). "Scream Factory to issue Tobe Hooper's Lifeforce & Hammer's Vampire Lovers on Blu-ray this April - Horror Movie News | Arrow in the Head". Joblo.com. Retrieved 2013-01-23.

External links

- Lifeforce at the Internet Movie Database

- Lifeforce at Rotten Tomatoes

- Lifeforce at Box Office Mojo

- Lifeforce at AllMovie