Alpine Line

| Alpine Line | |

|---|---|

| Southeastern France | |

|

Block B1 at Rimplas | |

| Type | Defensive line |

| Site information | |

| Controlled by | France |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1930–40 |

| In use | 1935–69 |

| Materials | Concrete, steel |

| Battles/wars | Italian invasion of France |

The Alpine Line (French: Ligne Alpine) or Little Maginot Line (French: Petite Ligne Maginot) was the component of the Maginot Line that defended the southeastern portion of France. In contrast to the main line in the northeastern portion of France, the Alpine Line traversed a mountainous region of the Maritime Alps, the Cottian Alps and the Graian Alps, with relatively few passes suitable for invading armies. Access was difficult for construction and for the Alpine Line garrisons. Consequently, fortifications were smaller in scale than the fortifications of the main Line. The Alpine Line mounted few anti-tank weapons, since the terrain was mostly unsuitable for the use of tanks. Ouvrage Rimplas was the first Maginot fortification to be completed on any portion of the Maginot Line, in 1928. The Alpine Line was unsuccessfully attacked by Italian forces during the Italian invasion of France in 1940. Following World War II, some of the larger positions of the Alpine Line were retained in use through the Cold War.

Concept

As France studied measures to protect its northeastern frontier with Germany, a parallel effort was made to examine the improvement of France's defenses against Italy in the southeast. France's Italian border was a relic of the 1860 Treaty of Turin in which the Duchy of Savoy and the County of Nice were incorporated into France. The treaty boundary roughly followed the crest of the Maritime Alps inland through the Cottian Alps to Switzerland. The precise line of demarcation left the upper reaches of many westward-draining valleys in Italian hands, thus giving Italy positions on high points overlooking French territory,[1] most notably Fort Chaberton on Mont Chaberton, which threatened Briançon.[2]

The region had been extensively fortified in the seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, most notably by Vauban, whose fortifications of Briançon have been designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and by Raymond Adolphe Séré de Rivières in the late nineteenth century, who expanded the Fort de Tournoux and other fortifications in the area as part of the Séré de Rivières system of fortifications.[3] Passage through the Alps was possible only at a series of comparatively low passes, and movement toward the major cities of southeastern France such as Lyon, Grenoble or Nice was possible only along a series of deep river valleys. Defenses therefore tended to concentrate in consistent locations:

- Bourg-Saint-Maurice in the Tarentaise, facing the Little St Bernard Pass

- Modane in the Maurienne, facing the Mont Cenis pass

- Briançon, facing the Col de Montgenèvre

- Barcelonnette, facing the Col de Larche

- Approaches to Nice from the north, with defenses in the Tinée and Vesubie valleys, around Sospel and on the Authion massif

- Menton and Nice, guarding the coastal road and railway line[4]

In 1925 General Charles Nollet, the Minister of War, directed General Jean Degoutte to survey the southeastern frontier and to make recommendations for their defense. Degoutte's proposal used principles of defense in depth to economize on manpower and funds, which were needed for the main Maginot defenses in northeastern France. The still-ambitious plan proposed in 1927 envisioned a series of fortified positions right on the frontier divides at every potential crossing, backed by thirty-six centers of resistance, each with fourteen infantry casemates and twelve infantry shelters, a total of about one thousand blockhouses. Costs were estimated at 250 million francs.[5]

The proposed plan was criticized for placing the fortifications too far forward by the Commission de Defense, but the overall organization was approved by Minister of War (and former Prime Minister) Paul Painlevé, with a strategy of fortifying Menton, Sospel and the valleys of the Vésubie and Tinée. Revisions in late 1927 proposed about 400 positions at a cost of between 400 million and 500 million francs.[6] The plan was altered in 1928 by General Fillonneau, who proposed to concentrate fortifications along potential invasion axes, rather than along a continuous line. The geographic emphasis remained on Menton and Sospel, but the concept of frontal confrontation was replaced by a strategy of attack from the flanks of a potential advance. Fillonneau was assisted by the new management organization for the Maginot fortifications, the Commission d'Organisation des Régions Fortifiés, or CORF. The proposal was estimated to cost 700 million francs to build 103 ouvrages and to reconstruct 28 old fortifications. An initial phase, designed to protect Nice, was estimated to cost 205 million francs[7]

Unlike the relatively thin, linear defenses of the northeast, the revised Alpine fortifications extended some distance back from the frontier, with forward defenses supported by rearward defenses, compartmentalized by the terrain into distinct sectors. A final proposal in 1930 established a scaled-back, prioritized programme of 362 million francs to be executed in two phases, with the second phase to cost an additional 62 million francs.[8]

Description

As with the main Maginot Line of the northeast, positions took the form of concrete-encased strongpoints linked by underground tunnels, which housed living quarters, magazines and utilities for the ouvrage. Larger ouvrages were provided with 600 mm (1 ft 11 5⁄8 in) narrow gauge rail lines to move materials and munitions, although unlike the northeastern positions, none were electrified. Because of the mountainous terrain and the vertical character of the sites chosen for fortification, individual blocks typically emerged from rock faces in a steep hillside or cliff with mined galleries within under rock cover. By comparison, most northeastern ouvrages were semi-submerged into the gently rolling soil with galleries deeply buried beneath earth cover. Many of the high-altitude petits ouvrages could only be built during the brief Alpine summer, leading to extended construction schedules, and causing many of these high outposts to be uncompleted at the outbreak of war in 1940.[9]

In addition to the linked complexes of blockhouses that formed the grand and petit ouvrages, the country around and between each position was provided with isolated blockhouses, observation points, shelters (or abris), outposts (avants postes) and batteries, using much the same vocabulary of rounded concrete forms as the primary line of fortifications. These positions allowed the use of mobile supporting artillery, and provided rallying and control points for the necessary infantry support in the country between strongpoints, as the security of the border did not and could not depend on subterranean fortifications alone. The disposition of forward outposts, backed by heavier fortifications some kilometers to the rear, provided a defense in depth that was, in the case of the Alpine fortifications, supported by the difficult terrain.[10]

Organization

1: Fortified Sector of Savoy

2-6: Fortified Sector of Savoy

7-12: Fortified Sector of Dauphiné

14-27: Fortified Sector of the Maritime Alps.

For a full list and details on the various strong points, see List of Alpine Line ouvrages

The Alpine Line was divided into three major sectors. From north to south, they were:

- Fortified Sector of Savoy (secteur fortifié de Savoie), divided into two principal sections, the Tarentaise valley around Bourg-Saint-Maurice, and the Maurienne valley around Modane.[11]

- Fortified Sector of the Dauphiné (secteur fortifié du Dauphiné), protecting Briançon and the Ubaye Valley opposite the Col de Larche.[12]

- Fortified Sector of the Maritime Alps (secteur fortifié des Alpes-Maritimes), covering the Tinée and Vésubie valleys and the coast around Sospel and Menton.[13]

In addition, the area to the north of the principal fortifications was organized as the Defensive Sector of the Rhône, with virtually no fixed fortifications, since it faced neutral Switzerland.[14]

The Alpine region was under the overall command of the Army of the Alps, General René Olry in command at Valence. Its chief units were the 14th Army Corps in the SF Savoy and SF Dauphiné, and the 15th Corps in the SF Maritime Alps.[14]

Construction

Work had already begun on Ouvrage Rimplas, which was in fact the first Maginot ouvrage to be built in either the northeast or southeast. The construction contract was signed 7 September 1928 with incomplete plans.[15] Rimplas was a prototype project, not representative of other alpine or Maginot positions. CORF took over responsibility for construction in 1931, standardizing design practices, although each project was closely adapted to local circumstances.[16] Construction was made difficult by poor access, high altitude and a short construction season.In 1931 work commenced at twenty-two sites.[17] In 1932 Ouvrage Cap Martin was sufficiently complete that it could be used in an emergency.[18] Work continued through 1936, even though CORF had been disestablished at the end of 1935. While most of the larger positions were complete, a number of the smaller, higher-altitude positions were never completed in time for war in 1940. From 1937, the main d'oeuvre Militaire (MOM) built a number of light positions and blockhouses, usually in locations close to the frontier.[19] Many of the MOM positions were incomplete in 1940.[20]

Compared with the northeastern Maginot positions, the Alpine fortifications made comparatively little use of retracting turrets, using instead concreted casemates in mountainsides surveying prepared fields of fire. The Alpine Line featured relatively few artillery ouvrages, tending instead to use mixed-arms positions that combined artillery casemates and infantry positions. The main fortifications were supported by infantry shelters, or abris, of both the "passive", lightly armed type, and "active" abris with heavier armament. Some of the mountaintop gros ouvrages used aerial tramways for their primary means of access. Military roads were often constructed in the absence of existing access. All of the large positions were provided with subterranean barracks and central utility plants.[21] Nearly all fortifications were excavated from solid rock. Coverage could therefore be reduced compared to the ouvrages of the northeast, which were at depths of up to 30 metres (98 ft) in deep soil to resist heavy siege artillery.[22] Independent means of power generation were a necessity in the absence of a utility distribution system. Likewise, telephone communication was problematic, with many positions using line-of-sight optical semaphores for communication.[23]

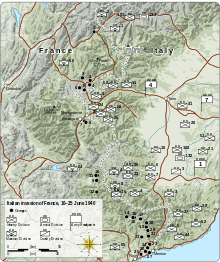

June 1940

Like the main Maginot Line did with the Germans, the Alpine Line achieved the goal of preventing the Italians from advancing through the protected areas. And, as the Italians had no alternative but to directly confront the fortifications, the south of France was completely protected from the Italian advance. An advance along the main coastal road was delayed by stiff resistance at the Casemate du Pont Saint Louis on the border at Menton, which was manned by seven men led by a non-commissioned officer and was supported by main-line fortifications at Ouvrage Cap Martin.[24][25] A direct assault on Cap Saint Martin was suppressed by the ouvrage itself, supported by artillery fire from Ouvrage Mont Agel[26]

Two more attacks were mounted, in the areas of Briançon and the Little St Bernard Pass, with little effect due to weather and the difficult terrain. Positions in the high Alps were shelled by Italian forces but were not directly attacked. Ouvrage Barbonnet traded fire with Italian positions prior to the armistice of 25 June 1940.

Vallo Alpino

The Italian counterpart to the Alpine Line was Italy's Alpine Wall (Vallo Alpino), the western portions of which faced the Alpine Line across the Alpine Valleys.

See also

- List of works on the Alpine Line

- List of all works on the main Maginot Line of the northeast

- Alpine Wall

References

- ↑ Mary, Tome 4, p. 5

- ↑ Mary, Tome 4, p. 6

- ↑ Mary, Tome 4, pp. 4-6

- ↑ Mary, Tome 4, pp. 5-6

- ↑ Mary, Tome 4, p. 8

- ↑ Mary, Tome 4, p. 9

- ↑ Mary, Tome 4, pp. 10-11

- ↑ Mary, Tome 4, pp. 13-14

- ↑ Kauffmann, pp.60-68

- ↑ Mary, Tome 4, p. 34

- ↑ Mary, Tome 5, pp. 8-22

- ↑ Mary, Tome 5, pp. 23-44

- ↑ Mary, Tome 5, pp. 45-73

- 1 2 Mary, Tome 5, pp. 4-5

- ↑ Mary, Tome 4, p. 16

- ↑ Mary, Tome 4, p. 18

- ↑ Mary, Tome 4, p. 19

- ↑ Mary, Tome 4, p. 23

- ↑ Mary, Tome 4, pp. 24-25

- ↑ Mary, Tome 4, p. 33

- ↑ Mary, Tome 4, pp. 42-62

- ↑ Mary, Tome 2, p. 117

- ↑ Kauffmann, pp. 66-67

- ↑ Mary, Tome 4, page 29

- ↑ Horne, Alistair; To Lose a Battle; France 1940. p. 565 ISBN 978-0-14-013430-8

- ↑ Puelinckx, Jean; Aublet, Jean-Louis; Mainguin, Sylvie (2010). "Mont Agel (forteresse du)". Index de la Ligne Maginot (in French). fortiff.be. Retrieved 25 January 2010.

Bibliography

- Allcorn, William. The Maginot Line 1928-45. Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2003. ISBN 1-84176-646-1

- Kaufmann, J.E. and Kaufmann, H.W. Fortress France: The Maginot Line and French Defenses in World War II, Stackpole Books, 2006. ISBN 0-275-98345-5

- Kaufmann, J.E., Kaufmann, H.W., Jancovič-Potočnik, A. and Lang, P. The Maginot Line: History and Guide, Pen and Sword, 2011. ISBN 978-1-84884-068-3

- Mary, Jean-Yves; Hohnadel, Alain; Sicard, Jacques. Hommes et Ouvrages de la Ligne Maginot, Tome 1. Paris, Histoire & Collections, 2001. ISBN 2-908182-88-2 (French)

- Mary, Jean-Yves; Hohnadel, Alain; Sicard, Jacques. Hommes et Ouvrages de la Ligne Maginot, Tome 4 - La fortification alpine. Paris, Histoire & Collections, 2009. ISBN 978-2-915239-46-1 (French)

External links

- Fortiff.be, detailed information on all Maginot fortifications (French)

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Maginot Line. |