Little Orphant Annie

| by James Whitcomb Riley | |

Mary Alice "Allie" Smith, Riley's inspiration for the poem | |

| Original title | The Elf Child |

|---|---|

| First published in | Indianapolis Journal |

| Country | United States |

| Publication date | November 15, 1885 |

| Media type | Newspaper |

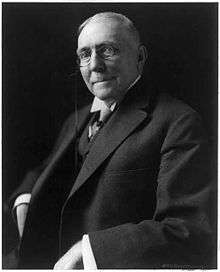

"Little Orphant Annie" is an 1885 poem written by James Whitcomb Riley and published by the Bowen-Merrill Company. First titled "The Elf Child", the name was changed by Riley to "Little Orphant Allie" at its third printing; however, a typecasting error during printing renamed the poem to its current form. Known as the "Hoosier poet", Riley wrote the rhymes in nineteenth-century Hoosier dialect. As one of his most well known poems, it served as the inspiration for the character Little Orphan Annie upon whom was based a comic strip, plays, radio programs, television shows, and movies.

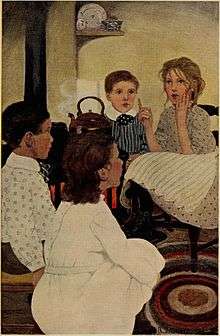

The subject was inspired by Mary Alice "Allie" Smith, an orphan living in the Riley home during her childhood. The poem contains four stanzas; the first introduces Annie and the second and third are stories she is telling to young children. Each story tells of a bad child who is snatched away by goblins as a result of their misbehavior. The underlying moral and warning is announced in the final stanza, telling children that they should obey their parents and be kind to the unfortunate, lest they suffer the same fate.

Background

James Whitcomb Riley was a poet who achieved national fame in the United States during late nineteenth and early twentieth century. "Little Orphant Annie" is one of Whitcomb's most well known poems.[1] Originally published in the Indianapolis Journal on November 15, 1885 under the title "The Elf Child", the poem was inspired by a girl named Mary Alice "Allie" Smith.

Mary Alice Smith was born near Liberty, Union County Indiana 25 September 1850. She lived on a small farm with her parents until (as one story goes) both parents died when she was about nine years old. Some stories say that Mary's mother died with she was very young and her father, Peter Smith, died when she was ten. Other evidence points to her father being incarcerated at the time. What ever the cause she was considered an orphan. Mary's uncle, a John Rittenhouse, came to Union County and took the young orphan to his home in Greenfield where he "dressed her in black" and "bound her out to earn her board and keep". Mary Alice was taken in by Captain Reuben Riley as a "bound" servant to help his wife Elizabeth Riley with the housework and her four children; John, James, Elva May and Alex. As was customary at that time, she worked alongside the family to earn her board.[2] In the evening hours, she often told stories to the younger children, including Riley. The family called her a "Guest" not a servant and treated her like she was part of their family. Smith did not learn she was the inspiration for the character until the 1910s when she visited with Riley.[3]

Riley had previously presented a fictionalized version of Mary Alice Smith in his short story “Where Is Mary Alice Smith?,” published in The Indianapolis Journal of 30 September 1882. In it, Mary Alice arrives at her benefactor family’s home and wastes no time in telling the children a grisly story of murder by decapitation and then later introduces them to her soldier friend Dave who is soon killed upon going off to war. The plot of this short story was heavily incorporated into the 1918 movie adaptation as well as Johnny Gruelle’s 1921 storybook.[4]

Both “The Elf Child” and “Where Is Mary Alice Smith?” were printed in book form for the first time in 1885 in The Boss Girl.[5]

“The Elf Child” kept its original title in its first two printings, but Riley decided to change its title to "Little Orphant Allie" in an 1889 printing. The printing house incorrectly cast the typeset during the printing, unintentionally renaming the poem to "Little Orphant Annie". Riley at first contacted the printing house to have the error corrected, but decided to keep the misprint because of the poem's growing popularity.[3][6]

When reprinted in The Orphant Annie Book in 1908, the poem was given an additional, introductory verse (“Little Orphant Annie she knows riddles, rhymes and things! …”).[7]

During the 1910s and 1920s, the title became the inspiration for the names of Little Orphan Annie and the Raggedy Ann doll, created by fellow Indiana native Johnny Gruelle.[8][9] The rhyme's popularity led it to being reprinted many times. It was later compiled with a number of other children's poems in an illustrated book and sold.[10]

The verses of the poem detail the scary stories told by Annie when her housework was done, repeating the phrase "An' the Gobble-uns 'at gits you ef you don't watch out!." [sic] It was popular among children, and many of the letters Whitcomb received from children commented on the poem. It remains a favorite among children in Indiana and is often associated with Halloween celebrations.[11]

Poem

|

|

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

|

"Little Orphant Annie"

A 2010 reading of the poem |

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

Riley recorded readings of several of his poems for the phonograph during the early twentieth century. Only four of the readings were ever released to the public; one was "Little Orphant Annie". Written in nineteenth century Hoosier dialect, the words can be difficult to read in modern times; however, its style helped feed its popularity at the time of its composition.[12] Riley achieved fame not just for writing poetry, but also from his readings. Like most of his poetry, "Little Orphant Annie" was written to achieve the best effect when read aloud.[1]

The poem consists of four stanzas, each with twelve lines. Riley dedicated his poem "to all the little ones," which served as an introduction to draw the attention of his audience when read aloud. The alliteration, parallels, phonetic intensifiers and onomatopoeia add effects to the rhymes that become more detectable when read aloud. The exclamatory refrain ending each stanza is spoken with more emphasis.[13] The poem is written in the first person and in a regular iambic meter. It begins by introducing Annie, and then sets a mood of excitement by describing the children eagerly gathering to hear her stories. The next three stanzas are each a story which Annie tells the children. Each story tells of a bad child who is snatched away by goblins and has an underlying moral which is announced in the final stanza, encouraging children to obey their parents and teachers, help their loved ones, and care for the poor and disadvantaged.[11][13]

- Little Orphant Annie

- Little Orphant Annie's come to our house to stay,

- An' wash the cups an' saucers up, an' brush the crumbs away,

- An' shoo the chickens off the porch, an' dust the hearth, an' sweep,

- An' make the fire, an' bake the bread, an' earn her board-an'-keep;

- An' all us other children, when the supper-things is done,

- We set around the kitchen fire an' has the mostest fun

- A-list'nin' to the witch-tales 'at Annie tells about,

- An' the Gobble-uns 'at gits you

- Ef you

- Don't

- Watch

- Out!

- Wunst they wuz a little boy wouldn't say his prayers,--

- An' when he went to bed at night, away up-stairs,

- His Mammy heerd him holler, an' his Daddy heerd him bawl,

- An' when they turn't the kivvers down, he wuzn't there at all!

- An' they seeked him in the rafter-room, an' cubby-hole, an' press,

- An' seeked him up the chimbly-flue, an' ever'-wheres, I guess;

- But all they ever found wuz thist his pants an' roundabout:--

- An' the Gobble-uns 'll git you

- Ef you

- Don't

- Watch

- Out!

- An' one time a little girl 'ud allus laugh an' grin,

- An' make fun of ever' one, an' all her blood-an'-kin;

- An' wunst, when they was "company," an' ole folks wuz there,

- She mocked 'em an' shocked 'em, an' said she didn't care!

- An' thist as she kicked her heels, an' turn't to run an' hide,

- They wuz two great big Black Things a-standin' by her side,

- An' they snatched her through the ceilin' 'fore she knowed what she's about!

- An' the Gobble-uns 'll git you

- Ef you

- Don't

- Watch

- Out!

- An' little Orphant Annie says, when the blaze is blue,

- An' the lamp-wick sputters, an' the wind goes woo-oo!

- An' you hear the crickets quit, an' the moon is gray,

- An' the lightnin'-bugs in dew is all squenched away,--

- You better mind yer parunts, an' yer teachurs fond an' dear,

- An' churish them 'at loves you, an' dry the orphant's tear,

- An' he'p the pore an' needy ones 'at clusters all about,

- Er the Gobble-uns 'll git you

- Ef you

- Don't

- Watch

- Out!

Film adaptations

"Little Orphant Annie" was made into a silent film by the Selig Polyscope Company in 1918, featuring Colleen Moore as Annie. She had previously been in A Hoosier Romance, also based on Riley's work.[14] Riley also appeared in the film as the silent narrator.

A short animated film based on the poem was released by Soyuztelefilm studio in Russia in 1992, directed by Yulian Kalisher. The poem was translated into Russian by Oleg Yegorov.[15]

Derivative work

In The Orphant Annie Story Book (1921), author Johnny Gruelle augments the character’s background story and goes to great lengths to soften her image, portraying her as telling pleasant tales of fairies, gnomes and anthropomorphic animals rather than her characteristic horror stories.[16]

In Popular Culture

In the TV series Getting On, the character of Birdy Lamb recites part of the poem at the end of Episode 3 of Season 3. The last stanza is also recited by two girls and the character Little Ann Sliger while jumping rope in the movie Texas Killing Fields ( 2011)

Notes

- 1 2 Pfeiler, p. 109

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 33

- 1 2 "The Raggedy Man and Little Orphant Annie". Indiana University. Retrieved 2010-01-08.

- ↑ Note in The Complete Works of James Whitcomb Riley in Which the Poems, Including a Number Heretofore Unpublished, Are Arranged in the Order in Which They Were Written, Together with Photographs, Bibliographic Notes, and a Life Sketch of the Author, ed. Edmund Henry Eitel, “biographical edition,” vol. 6, Indianapolis: Bobbs‐Merrill Co., 1913, 403.

- ↑ James Whitcomb Riley, The Boss Girl: A Christmas Story, and Other Sketches, Indianapolis: Bowen‐Merrill Co., 1885, 177–196.

- ↑ James Whitcomb Riley, “Little Orphant Annie,” Old‐Fashioned Roses, Indianapolis: Bowen‐Merrill Co., 1889, 111–113.

- ↑ James Whitcomb Riley, “Little Orphant Annie,” The Orphant Annie Book, Indianapolis: Bobbs‐Merrill Co., 1908, unpaginated.

- ↑ "Ann's Story". The Raggedy Ann & Andy Museum. Retrieved 2010-04-10.

- ↑ "Moment of Indiana History". Purdue University. Archived from the original on May 19, 2011. Retrieved 2010-04-10.

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 241

- 1 2 "James Whitcomb Riley". Our Land, Our Literature. Ball State University. Archived from the original on May 16, 2008. Retrieved 2010-04-10.

- ↑ Pfeiler, p. 111

- 1 2 Pfeiler, p. 110

- ↑ "Little Orphant Annie". American Film Institute. Retrieved 2010-04-10.

- ↑ "Little Orphant Annie" (in Russian). Retrieved 2010-04-10.

- ↑ Johnny Gruelle, The Orphant Annie Story Book, Indianapolis: Bobbs‐Merrill Co., 1921.

References

- Pfeiler, Martina (2003). Sounds of poetry: contemporary American performance poets. Gunter Narr Verlag. ISBN 3-8233-4664-4.

- Van Allen, Elizabeth J. (1999). James Whitcomb Riley: a life. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-33591-4.

External links

Texts

- "Little Orphant Annie" - Full text from the Complete Works, 1916.