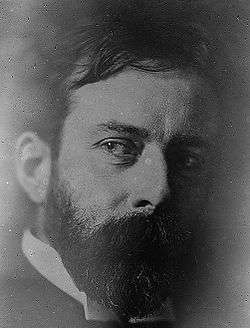

Lorado Taft

| Lorado Taft | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

April 29, 1860 Elmwood, Illinois |

| Died |

October 30, 1936 (aged 76) Chicago, Illinois |

| Nationality | American |

| Known for | Sculpture |

Lorado Zadoc Taft (April 29, 1860 – October 30, 1936) was an American sculptor, writer and educator. Taft was born in Elmwood, Illinois, in 1860 and died in his home studio in Chicago in 1936.[1] Taft was the father of Representative Emily Taft Douglas, father-in-law to her husband, Senator Paul Douglas, and a distant relative of U.S. President William Howard Taft.

Early years and education

After being homeschooled by his parents, Taft earned his bachelor's degree (1879) and master's degree (1880) from the Illinois Industrial University (later renamed the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign) where his father was a professor of geology.[2] The same year he left for Paris to study sculpture, yet maintained his connections with the university for the rest of his life. In 1929, he dedicated his sculpture of Alma Mater on the University of Illinois campus. Taft envisioned his Alma Mater as a benign and magnificent woman, about fourteen feet high and dressed in classical draperies, rising from a throne and advancing a step forward with outstretched arms in a gesture of generous greeting to her children. Two figures behind her on either side represent the university’s motto, Learning and Labor.[3]

In Paris, Taft attended the École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts from 1880 to 1883, where he studied with Augustin Dumont, Jean-Marie Bonnassieux and Jules Thomas. His record there was outstanding; he was cited as "top man" in his studio and twice exhibited at the Salon. Upon returning to the United States in 1886, he settled in Chicago. He taught at The School of the Art Institute of Chicago, a job he would hold until 1929. In addition to work in clay and plaster, Taft taught his students marble carving, and had them work on group projects. He also lectured at the University of Chicago and the University of Illinois.[4]

In 1892, while the art community of Chicago was preparing for the World's Columbian Exposition of 1893, chief architect Daniel Burnham expressed concern to Taft that the sculptural adornments to the buildings might not be finished on time. Taft asked if he could employ some of his female students as assistants (it was not socially accepted for women to work as sculptors at that time) for the Horticultural Building. Burnham responded, "Hire anyone, even white rabbits if they'll do the work." From that arose a group of talented women sculptors known as "the White Rabbits": Enid Yandell, Carol Brooks MacNeil, Bessie Potter Vonnoh, Janet Scudder, Julia Bracken and Ellen Rankin Copp.

Later, another former student, Frances Loring, noted that Taft used his students' talents to further his own career, a not uncommon situation. In general, history has given Taft credit for helping to advance the status of women as sculptors.

In 1898, Taft was a founding member of the Eagle's Nest Art Colony in the small town of Oregon, Illinois. Taft designed the Columbus Fountain at Union Station in Washington, D.C., in collaboration with Daniel Burnham.

Later years

As Taft grew older, his eloquence and compelling writing led him, along with Frederick Ruckstull, to the forefront of sculpture's conservative ranks, where he often served as a spokesperson against the modern and abstract trends that developed during his lifetime. Taft's frequent lecture tours for the Chautauqua gave him a broad, popular celebrity status.

In some settings, Taft is better known for his writings than for his sculpture. In 1903, Taft published The History of American Sculpture, the first survey of the subject. The revised 1925 version was to remain the standard reference on the subject until Wayne Craven published "Sculpture in America" in 1968. In 1921, Taft published Modern Tendencies in Sculpture, a compilation of his lectures given at the Art Institute of Chicago. At the time, it offered a distinct perspective on the development of European sculpture; today, the book continues to be regarded as an excellent survey of American sculpture in the early years of the 20th century.

Taft was a member of the National Academy of Design, the National Institute of Arts and Letters, and the American Academy of Arts and Letters; he headed the National Sculpture Society in the 1920s and served on the Board of Art Advisors of Illinois. He received numerous awards, prizes, and honorary degrees, served on the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts from 1925 to 1929, and was an honorary member of the American Institute of Architects. His papers reside in collections at the Smithsonian Archives of American Art, the University of Illinois, and the Art Institute of Chicago.[5]

Taft was active until the end of his life. The week before he died, he attended the Quincy, Illinois, dedication ceremonies for his sculpture celebrating the Lincoln-Douglas debates.[1]

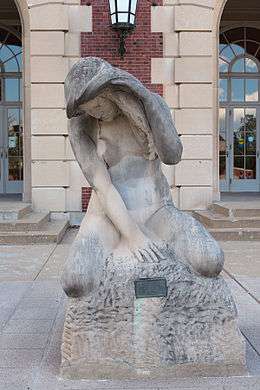

He left unfinished a vast work to be called the "Fountain of Creation" which he planned to place at the opposite end of the Chicago Midway from the "Fountain of Time."[6] Parts of this work were donated to the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign and are now at the library and Foellinger Auditorium. The University named a dormitory and a street in Taft's honor.[7]

In 1965, his Chicago workplace was designated a National Historic Landmark as Lorado Taft Midway Studios.[8]

Sculptor's body of work

Lorado Taft was a member of the National Sculpture Society and exhibited at both their 1923 and 1929 shows. Today Taft is best remembered for his various fountains.

The University of Illinois Archives has a series of photographs of most of Lorado Taft's important works, including many of their construction and preliminary models.[9]

Fountain of Time

Following more than a dozen years of work, Taft's Fountain of Time was unveiled at the west end of Chicago's Midway Plaisance in 1922. Based on poet Austin Dobson's lines — "Time goes, you say? Ah no, Alas, time stays, we go." — the fountain shows a cloaked figure of time observing the stream of humanity flowing past.

Pioneer & Patriot Groups for the Louisiana State Capitol Building

The last major commission that Taft completed was two groups for the front entrance to the Louisiana State Capitol Building, dedicated in 1932.

Students and assistants

During his long career Taft acted as a mentor and teacher for many sculptors including:

- Enrique Alférez

- Jean Pond Miner Coburn

- Alice Cooper

- Leonard Crunelle

- Ulric Ellerhusen

- Paul Fjelde

- Sherry Edmundson Fry

- Waylande Gregory

- Carl Augustus Heber

- Frederick Hibbard

- Mary Lawrence

- Evelyn Beatrice Longman

- Frances Loring

- Carol Brooks MacNeil

- Helen Farnsworth Mears

- Charles Mulligan

- William Clark Noble

- C. Adrian Pillars

- Trygve Rovelstad

- Belle Kinney Scholz

- Janet Scudder

- Clara Sorensen

- John Storrs

- Charles Umlauf

- Bessie Potter Vonnoh

- Nellie Walker

- Julia Bracken Wendt

- Florence Wyle

- Enid Yandell

Selected commissions

- LaFayette Fountain, Lafayette, Indiana, 1887.

- Schuyler Colfax, University Park, Indianapolis, Indiana, 1887.

- George Washington, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, 1905-09. Created for the 1909 Alaska–Yukon–Pacific Exposition.

- Eternal Silence, Graves Memorial, Graceland Cemetery, Chicago, Illinois, 1909.

- Chief Paduke Statue, Jefferson Street, Paducah, Kentucky, 1909.

- Black Hawk Statue Monument, aka Eternal Indian, Oregon, Illinois, 1911.

- The Solitude of the Soul, Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois, 1911-14.

- Columbus Fountain, in front of Union Station, Washington, D.C., 1912.

- Fountain of the Great Lakes, Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois, 1913.

- Seated Woman With Children aka Music, Chicago, Illinois, 1915

- Thatcher Memorial Fountain, Denver, Colorado, 1918.

- Two Boys with Dolphins Fountain, Oregon, Illinois, ca. 1920

- Fountain of Time, Chicago, Illinois, 1922.

- William A. Foote Memorial, Woodland Cemetery, Jackson, Michigan, 1923.

- Lincoln the Lawyer, Urbana, Illinois, 1927.

- Alma Mater, University of Illinois, 1929.

- Frances Elizabeth Willard (plaque), Indiana Statehouse, Indianapolis, Indiana, 1929.[10]

- The Crusader, Lawson Monument, Graceland Cemetery, Chicago, Illinois, 1931.

- Two Groups: The Pioneers and The Patriots, Louisiana State Capitol, Baton Rouge, Louisiana, 1932.On

- Ontario Sends Greetings to the Sea, eleventh issue of the Society of Medalists, 1935.

- Bas-relief of Lincoln - Douglas Debate, Quincy, October 13, 1858, Quincy, Illinois, 1936.

- Heald Square Monument (Robert Morris - George Washington - Haym Salomon), Chicago, Illinois, 1936-41. Completed by Leonard Crunelle, Nellie Walker and Fred Torrey following Taft's 1936 death.

War memorials

- 4th Michigan Infantry Monument, Gettysburg Battlefield, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, 1889.

- General Ulysses S. Grant Monument, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, 1889.

- Student Veteran Memorial, Hillsdale College, Hillsdale, Michigan, 1895.

- Defense of the Flag, Withington Park, Jackson, Michigan, 1904.

- The Soldiers' Monument, Oregon, Illinois, 1916.

LaFayette Fountain (1887), Tippecanoe County Courthouse, Lafayette, Indiana.

LaFayette Fountain (1887), Tippecanoe County Courthouse, Lafayette, Indiana._Control_IAS_76008067.jpg) Schuyler Colfax (1887), University Park, Indianapolis, Indiana.

Schuyler Colfax (1887), University Park, Indianapolis, Indiana. 4th Michigan Infantry Monument (1889), Gettysburg Battlefield, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.

4th Michigan Infantry Monument (1889), Gettysburg Battlefield, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Defense of the Flag (1904), Jackson, Michigan.

Defense of the Flag (1904), Jackson, Michigan. George Washington (1905–09), University of Washington, Seattle.

George Washington (1905–09), University of Washington, Seattle. Fountain of the Great Lakes (1907–13), Art Institute of Chicago.

Fountain of the Great Lakes (1907–13), Art Institute of Chicago. Black Hawk Statue (1908–11), Lowden State Park, Oregon, Illinois.

Black Hawk Statue (1908–11), Lowden State Park, Oregon, Illinois..jpg) The Solitude of the Soul (1911–14), Art Institute of Chicago.

The Solitude of the Soul (1911–14), Art Institute of Chicago. Columbus Fountain (1912), Union Station, Washington, D.C.

Columbus Fountain (1912), Union Station, Washington, D.C. Seated Woman With Children, (1915), Chicago Illinois

Seated Woman With Children, (1915), Chicago Illinois The Soldiers' Monument (1916), Oregon, Illinois.

The Soldiers' Monument (1916), Oregon, Illinois. Thatcher Memorial Fountain (1918), Denver, Colorado.

Thatcher Memorial Fountain (1918), Denver, Colorado. Two Boys with Dolphins (ca. 1920), Oregon, Illinois.

Two Boys with Dolphins (ca. 1920), Oregon, Illinois. Taft's self-portrait on the Fountain of Time (1922), Chicago, Illinois.

Taft's self-portrait on the Fountain of Time (1922), Chicago, Illinois. Foote Memorial (1923), Jackson, Michigan.

Foote Memorial (1923), Jackson, Michigan.

The Crusader (1931), Graceland Cemetery, Chicago, Illinois.

The Crusader (1931), Graceland Cemetery, Chicago, Illinois.- Lincoln - Douglas Debate, Quincy, October 13, 1858. (1936), Quincy, Illinois.

- Heald Square Monument (1936–41), Chicago, Illinois. Completed by Leonard Crunelle, Nellie Walker and Fred Torrey.

Notes

- 1 2 "Mr. Lorado Taft Dies; Leading Sculptor; Creator of Some of Country's Outstanding Monuments is Stricken at 76; Was Teacher in Chicago; Fountain of Time and Columbus Memorial in Washington Among Chief Works," New York Times. October 31, 1936.

- ↑ Taft's association with the University is commemorated by a street named in his honor.

- ↑ Allen Weller, Lorado Taft: The Chicago Years, Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2014, 197-8.

- ↑ Blanche Higgins Schroer, Landmark Review Project: Lorado Taft Midway Studios, National Park Service, 1965.

- ↑ Thomas E. Luebke, ed., Civic Art: A Centennial History of the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Commission of Fine Arts, 2013): Appendix B, 556.

- ↑ Taft Biography, University of Illinois Library, accessed May 16, 2012.

- ↑ Taft Hall 40°06′08″N 88°14′01″W / 40.1021°N 88.2337°W and Taft Drive, 40°06′11″N 88°13′45″W / 40.1030°N 88.2293°W

- ↑ Blanche Higgins Schroer (April 3, 1976). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination: Lorado Taft Midway Studios" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved 2009-06-27 and Accompanying 10 photos, exterior and interior, from 1975 and undated (2.97 MB)

- ↑ "An Inventory of the Lorado Taft Papers at the University of Illinois Archives. Mounted Photograph Collection - A series of photographs of most of Lorado Taft's important works, including many of their construction and preliminary models". uiuc.edu. Links to photographs

- ↑ Scherrer, Anton. "Our Town." Indianapolis Times. 18 April 1939.

Sources

- Bach, Ira and Mary Lackritz Gray, Chicago's Public Sculpture, University of Chicago Press, Chicago 1983

- Barnard, Harry, This Great Triumvirate of Patriots – The inspiring Story behind Lorado Taft's Chicago Monument to George Washington, Robert Morris and Haym Solomon, Follett Publishing, Chicago Illinois 1971

- Contemporary American Sculpture, The California Palace of the Legion of Honor, Lincoln Park, San Francisco, The National Sculpture Society 1929

- Craven, Wayne, Sculpture in America, Thomas Y. Crowell Co, New York 1968

- Exhibition of American Sculpture Catalogue, 156th Street of Broadway New York, The National Sculpture Society 1923

- Garvey, Timothy J., Public Sculptor – Lorado Taft and the Beautification of Chicago, University of Illinois Press, Urbana, Illinois 1988

- Goode, James M. The Outdoor Sculpture of Washington, D.C.'., Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C. 1974

- Kubly, Vincent, The Louisiana Capitol-Its Art and Architecture, Pelican Publishing Company, Gretna 1977

- Kvaran, Einar Einarsson, Architectural Sculpture of America, unpublished manuscript

- Lanctot, Barbara, A Walk Through Graceland Cemetery, Chicago Architecture Foundation, Chicago 1988

- Opitz, Glenn B, Editor, Mantle Fielding's Dictionary of American Painters, Sculptors & Engravers, Apollo Book, Poughkeepsie NY, 1986

- Rubenstein, Charlotte Streifer, American Women Sculptors, G.K. Hall & Co., Boston 1990

- Scheinman, Muriel, A Guide to the Art of the University of Illinois, University of Illinois Press, Urbana 1995

- Scherrer, Anton. "Our Town." Indianapolis Times. 18 April 1939.

- Taft, Lorado (1903). History of American Sculpture. New York: The MacMillan Company. p. 544.

- Taft, Lorado (1921). Modern Tendencies in Sculpture. University of Chicago Press. p. 152.

- Weller, Allen Stuart, Lorado in Paris – the Letters of Lorado Taft 1880–1885, University of Illinois Press, Urbana Illinois 1985.

- Weller, Allen Stuart, Lorado Taft: The Chicago Years, edited by Robert G. La France, Henry Adams, and Stephen Thomas, Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lorado Taft. |

- Works by or about Lorado Taft at Internet Archive

- Lorado Taft Papers, 1857-1953 University of Illinois Archives

- The Ryerson & Burnham Libraries: Archives Collection: Lorado Taft Collection, 1908-1938

- Descriptions and photographs of two works Defense of the Flag memorial and William A Foote memorial

- American Art American City: Lorado Taft Arbeat Chicago segment on WTTW's Chicago Tonight, May 15, 2008

Texts on Wikisource:

Texts on Wikisource: