Lucania

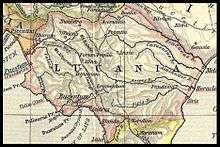

Lucania (Greek: Λευκανία, Leukania) was an ancient area of southern Italy. It was the land of the Lucani, an Oscan people. It extended from the Tyrrhenian Sea to the Gulf of Taranto. It bordered with Samnium and Campania in the north, Apulia in the east, and Bruttium in the south-west—at the top of the peninsula which now called Calabria. It thus comprised almost all the modern region of Basilicata, the southern part of the province of Salerno (theCilento area) and a northern portion of the province of Cosenza. The precise limits were the river Silarus in the north-west, which separated it from Campania, and the Bradanus, which flows into the Gulf of Taranto, in the east. The lower tract of the river Laus, which flows from a ridge of the Apennine Mountains to the Tyrrhenian Sea in an east-west direction, marked part of the border with Bruttium.

Geography

Almost the whole area is occupied by the Apennine Mountains, which here are an irregular group of lofty masses. The main ridge approaches the western sea, and continues from the lofty knot of mountains on the frontiers of Samnium, in a mostly southerly direction, to within a few miles of the Gulf of Policastro. From then on it is separated from the sea by only a narrow interval until it enters Bruttium. Just within the frontier of Lucania rises Monte Pollino, 7,325 ft (2,233 m), the highest peak in the southern Apennines. The mountains descend in a much more gradual slope to the coastal plain of the Gulf of Taranto. Thus the rivers which flow to the Tyrrhenian Sea are of little importance compared with those that descend towards the Gulf of Tarentum. Of these the most important are the Bradanus (Bradano), the Casuentus (Basento), the Aciris (Agri), and the Siris (Sinni). The Crathis, which forms at its mouth the southern limit of the province, belongs almost wholly to the territory of the Bruttii, but it receives a tributary, the Sybaris (Coscile), from the mountains of Lucania. The only considerable stream on the western side is the Silarus (Sele), which constitutes the northern boundary, and has two important tributaries in the Calor (Calore Lucano or Calore Salernitano) and the Tanager (Tanagro or Negro) which joins it from the south.

Etymology

There are several hypotheses on the origin of the name Lucania, inhabited by Lucani, an Osco-Samnite population from central Italy. Lucania might be derived from Greek λευκός, leukos meaning "white", cognate of Latin lux ("light"). According to another hypothesis, Lucania might be derived from Latin word lucus meaning "sacred wood" (cognate of lucere), or from Greek λύκος, lykos meaning "wolf".

History

The district of Lucania was so called from the people bearing the name Lucani (Lucanians) by whom it was conquered about the middle of the 5th century BC. Before that period it was included under the general name of Oenotria, which was applied by the Greeks to the southernmost portion of Italy. The mountainous interior was occupied by the tribes known as Oenotrians and Choni, while the coasts on both sides were occupied by powerful Greek colonies which doubtless exercised a protectorate over the interior (see Magna Graecia). The Lucanians were a southern branch of the Samnite or Sabellic race, who spoke the Oscan language. They had a democratic constitution save in time of war, when a dictator was chosen from among the regular magistrates. A few Oscan inscriptions survive, mostly in Greek characters, from the 4th or 3rd century BC, and some coins with Oscan legends of the 3rd century.[1] The Lucanians gradually conquered the whole country (with the exception of the Greek towns on the coast) from the borders of Samnium and Campania to the southern extremity of Italy. Subsequently the inhabitants of the peninsula, now known as Calabria, broke into insurrection, and under the name of Bruttians established their independence, after which the Lucanians became confined within the limits already described. After this we find them engaged in hostilities with the Tarentines, and with Alexander, king of Epirus, who was called in by that people to their assistance, 334 BC. In 298 BC (Livy x. II seq.) they made alliance with Rome, and Roman influence was extended by the colonies of Venusia (291 BC), Paestum (273), and above all Tarentum (272). Subsequently they were sometimes in alliance, but more frequently engaged in hostilities, during the Samnite wars. On the landing of Pyrrhus in Italy (281 BC) they were among the first to declare in his favor, and found themselves exposed to the resentment of Rome when the departure of Pyrrhus left his allies at the mercy of the Romans. After several campaigns they were reduced to subjection (272 BC). Notwithstanding this they espoused the cause of Hannibal during the Second Punic War (216 BC), and their territory during several campaigns was ravaged by both armies. The country never recovered from these disasters, and under the Roman government fell into decay, to which the Social War, in which the Lucanians took part with the Samnites against Rome (90–88 BC) gave the finishing stroke. In the time of Strabo the Greek cities on the coast had fallen into insignificance, and owing to the decrease of population and cultivation the malaria began to obtain the upper hand. The few towns of the interior were of no importance. A large part of the province was given up to pasture, and the mountains were covered with forests, which abounded in wild boars, bears and wolves. There were some fifteen independent communities, but none of great importance.

For administrative purposes under the Roman empire, Lucania was always united with the district of the Bruttii, a practice continued by Theodoric.[2] The two together constituted the third region of Augustus.

Cities and towns

The towns on the east coast were Metapontum, a few miles south of the Bradanus; Heraclea, at the mouth of the Aciris; and Sins, on the river of the same name. Close to its southern frontier stood Sybaris, which was destroyed in 510 BC, but subsequently replaced by Thurii. On the west coast stood Posidonia, known under the Roman government as Paestum; below that came Elea (Velia under the Romans), Pyxus, called by the Romans Buxentum, and Laüs, near the frontier of the province towards Bruttium. Of the towns of the interior the most considerable was Potentia, still called Potenza. To the north, near the frontier of Apulia, was Bantia (Aceruntia belonged more properly to Apulia); while due south from Potentia was Grumentum, and still farther in that direction were Nerulum and Muranum. In the upland valley of the Tanagrus were Atina, Forum Popilii and Consilinum (near Sala Consilina); Eburi (Eboli) and Volceii (Buccino), though to the north of the Silarus, were also included in Lucania. The Via Popilia traversed the district from N. to S., entering it at the NW. extremity; the Via Herculia, coming southwards from the Via Appia and passing through Potentia and Grumentum, joined the Via Popilia near the S.W edge of the district: while another nameless road followed the east coast and other roads of less importance ran W. from Potentia to the Via Popilia, N.E. to the Via Appia and E. from Grumentum to the coast at Heraclea. (T. As.)

Later use

The modern name Basilicata originates from the 10th century AD, when the area was under Byzantine control. The region was renamed and divided into Eastern and Western Lucania (Lucania Orientale and Lucania Ocidentale) for a short period of time during the Carbonari revolution of 1820–21, and from the latter half of the 19th century there was campaigning to reinstate the name. The change was made in 1932, in accordance with the fascist regime's appropriation of symbols from the Roman Empire, and was thus undone shortly after the war, in 1947. Lucania is still in vernacular use as a synonym to Basilicata. [3]

Notes

References

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "article name needed". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "article name needed". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.