Lullingstone Roman Villa

| Lullingstone Roman Villa | |

|---|---|

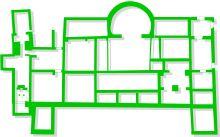

The enclosed interior of Lullingstone Villa | |

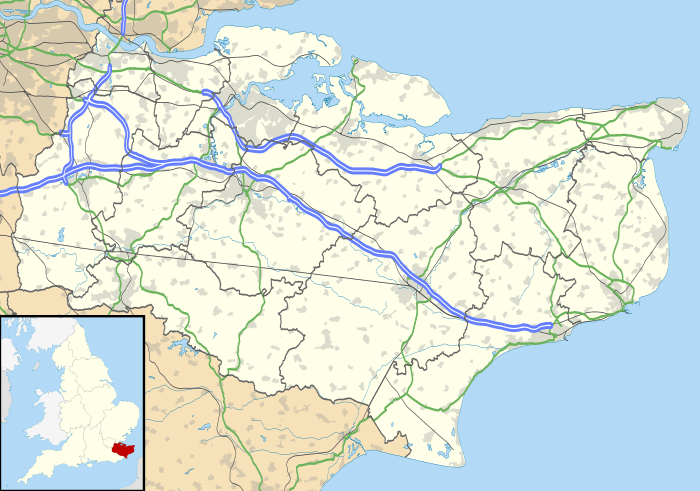

Location within Kent | |

| General information | |

| Architectural style | Romano-British Villa |

| Location |

Lullingstone grid reference TQ53016508 |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Coordinates | 51°21′50″N 0°11′47″E / 51.3640°N 0.1964°ECoordinates: 51°21′50″N 0°11′47″E / 51.3640°N 0.1964°E |

| Construction started | 1st century |

| Demolished | 5th century |

Lullingstone Roman Villa is a villa built during the Roman occupation of Britain, situated near the village of Eynsford in Kent, south eastern England. Constructed in the 1st century, perhaps around A. D. 80-90, the house was repeatedly expanded and occupied until it was destroyed by fire in the 5th century. The occupants were wealthy Romans or native Britons who had adopted Roman customs.

Some evidence found on site suggests that about A. D. 150, the villa was considerably enlarged and may have been used as the country retreat of the governors of the Roman province of Britannia. Two sculpted marble busts found in the cellar may be those of Pertinax, governor in 185-186, and his father-in-law, Publius Helvius Successus.[1]

In the Saxon period, the ruins of a Roman temple-mausoleum on the site of the villa were incorporated into a Christian chapel (Lullingstane Chapel) that was extant at the time of the Norman Conquest, one of the earliest known chapels in the country.

The villa is located in the Darent Valley, along with six others, including those at Crofton, Crayford and Dartford.[2]

History

Construction

The earliest stage of the villa was built around 82 AD. It was situated in an area near to several other villas, and was close to Watling Street, a Roman road by which travellers could move to and from Londinium to Durobrivae, Durovernum Cantiacorum, and the major Roman port of Rutupiæ (i.e., London, Rochester, Canterbury, and Richborough, respectively).[3]

Enlargement

Around AD 150 the villa was expanded and a heated bath block with hypocaust was added. Two marble busts from the 2nd century found in the cellar perhaps depict the owners or residents of the villa, which may have been the designated country retreat of the provincial governors. There is some evidence that the busts are those of Pertinax, governor of Britannia in 185-186, and his father.[4]

In the 3rd century, a larger furnace for the hypocaust as well as an expanded bath block were added, as were a temple-mausoleum and a large granary. In the 4th century, the dining room was equipped with a fine mosaic floor with one illustration of Zeus, disguised as a bull, abducting Europa and a second depicting Bellerophon killing the Chimera.[5]

Destruction and Rediscovery

Sometime early in the 5th century a fire destroyed the building, and it was abandoned and forgotten until its excavation in the 20th Century.[6]

The first discovery of the site was made in 1750, when workers fencing a deer park dug post holes through a mosaic floor, but no systematic excavations were done until the 20th century.[7] In 1939, a blown-down tree revealed scattered mosaic fragments. The villa was excavated in the period 1949–61 by archaeologists, and the ruins themselves were preserved under a specially-designed cover in the 1960s, when the villa was taken over by English Heritage, who opened the ruins to the public.

The building began to leak late in the 20th century and required a major £1.8m renovation and redisplay project in 2006-08 to make it safe to display fragile objects from the site in it.[8]

Rooms

Dining Room

The dining room, or triclinium, was situated in the centre of the main building, and was highly decorated with a pair of large mosaics on the floor dating to the mid-4th century.[10] One depicts the abduction of the princess Europa by the god Jupiter who is disguised as a bull,[11] whilst the other depicts Bellerophon slaying the Chimaera, whilst surrounded by four sea creatures. Surrounding these mosaics were smaller images depicting hearts, crosses and swastikas.

Pagan shrine and Christian chapel

One room of the building had been used as both a pagan shrine, and, later, as a Christian chapel, one of the earliest in Britain.

The original pagan shrine room was dedicated to local water deities, and a wall painting depicting three water nymphs dating from this period can still be seen in a niche in the room.[12] Just after the 3rd century, this niche had been covered over, as the whole room had been redecorated with white plaster painted with red bands,[13] and two busts of male figures had been placed in the room. Some scholars have theorised that at this point the inhabitants focused their worship on household deities and ancestor spirits, largely abandoning the worship of the water deities.[14]

In the 4th century the room above the pagan shrine was apparently converted to Christian use, with painted plaster on the walls, including a row of figures of standing worshipers, (orans), and a characteristic Christian Chi-rho symbol. Some of the paintings are now on display in the British Museum.[15]

According to English Heritage, which maintains the site:[16]

The evidence of the Christian house-church is a unique discovery for Roman Britain and the wall paintings are of international importance. Not only do they provide some of the earliest evidence for Christianity in Britain, they are almost unique – the closest parallels come from a house-church in Dura Europus, Syria.

Perhaps almost as remarkable as the discovery of the house-church is the possibility that pagan worship may have continued in the cult room below. What is not clear is whether this represented the family hedging their bets, trumpeting their apparent acceptance of Christianity, while trying to keep the old gods happy, or whether it represents some members of the family clinging to old beliefs in the face of the adoption of Christianity by others.

Graves

A Romano-Celtic temple-mausoleum complex was constructed around 300 AD to hold the bodies of two young people, those of a male and a female, in lead coffins. Although the young woman's coffin was robbed in antiquity, the other remained in situ and undisturbed, and is now on display at the site.

References

- ↑ "A Governor's Palace?" Lullingstone Roman Villa, English Heritage, accessed 15 June 2012.

- ↑ Lullingstone Roman Villa, Michael Fulford, page 17

- ↑ Lullingstone Roman Villa, Michael Fulford, page 18

- ↑ Times article, 30 July 2006

- ↑ Article on the Lullingstone mosaics

- ↑ Meates, Lt. Col. G.W. Lullingstone Roman Villa. p.33. London. Her Majesty's Stationery Office. 1984. 0-11-670035-1

- ↑ "History of Lullingstone Roman Villa," English Heritage, accessed 15 June 2012.

- ↑ Kennedy, Maev (24 July 2008). "New light thrown on Roman villa remains". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 24 July 2008.

- ↑ "From Paganism to Christianity," Lullinstone Roman Villa, English Heritage, accessed 15 June 2012.

- ↑ Lullingstone Roman Villa, Michael Fulford, page 14

- ↑ Lullingstone Roman Villa, Michael Fulford, page 28

- ↑ Lullingstone Roman Villa, Michael Fulford, page 8

- ↑ Lullingstone Roman Villa, Michael Fulford, page 7

- ↑ Lullingstone Roman Villa, Michael Fulford, page 9

- ↑ Murals from Lullingstone and other related artifacts on the British Museum website

- ↑ "Significance," Lullingstone Roman Villa, English Heritage, accessed 15 June 2012

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Roman villa, Lullingstone. |