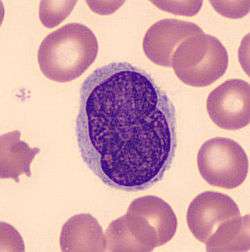

Lutzner cells

| Lutzner Cells | |

|---|---|

A histological view of Lutzner cells surrounded by erythrocytes in a blood smear. | |

Lutzner cells were discovered by Marvin A. Lutzner, Lucien-Marie Pautrier, and Albert Sézary. These cells are also referred to as Pautrier’s abscess, Sézary’s cell, or Sézary-Lutzner cells. They are a form of T-lymphocytes that has been mutated[1] This atypical form of T-lymphocytes contains T-cell receptors on the surface and is found in both the dermis and epidermis layers of the skin. Since Lutzner cells are a mutated form of T-lymphocytes, they develop in bone marrow and are transported to the thymus is order to mature.[2] The production and maturation stages occur before the cell has developed a mutation. Lutzner cells can form cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, which is a form of skin cancer.[3]

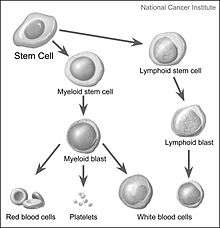

Development of Lutzner Cells

Lymphocytes are white blood cells that form from a blood stem cell, hemocytoblast, in bone marrow and travel to other parts of the body, normally specific lymphoid tissues, to mature. After being produced, the stem cell differentiates into lymphoid stem cells. Then, T-lymphocytes further mature and differentiate into lymphoblasts when the hormone thymosin is secreted from the thymus. Finally, specialized immune cells, B cells and T cells, and nonspecialized immune cells, nature killer cells, are created from the lymphoblasts. This process is referred to as Leukopoiesis. Lutzner cells are an atypical form of T-cell lymphocytes and are normally CD4+.[2] Lutzner cells develop because of clonal gene rearrangements in the T-cell receptor or antibody. This rearrangement occurs early in the differentiation process and creates novel T-cell receptors that mimic the structure of normal antibodies but are not able to function properly. This mutated form contains an enfolded nuclear membrane and has a cerebriform shape, resembling the shape and folds of the brain.[4] Lutzner cells can be best seen through electron microscopy because it is able to show the 3-D structure of the cell.

Distribution

Lutzner cells begin developing in bone marrow then travel to the thymus via the secretion of the hormone thymosin. The secretion allows them to differentiate and mature. Once the mutated cell is developed, it patiently waits in the thymus until an antigen presents itself.[2] When a cutaneous lymphocyte antigen is expressed in the skin, the CD4+ Lutzner cell travels to the epidermis and dermis layers of the skin in order to bind to the antigen.[4]

Antibody Mutation

Mature lymphocytes are part of the specific immune system because they recognize previous invaders and assist the body in attacking these invaders. These cells have antibodies present on the surface of the extracellular membrane, which contribute to the destruction of the invader or antigen. An antibody is a large protein created by plasma cells and is also known as an immunoglobulin. It binds to a specific antigen to initiate an immune response. T-cell antibodies bind to antigens such as virus infected cells or tumor cells.[2]

In Lutzner cells, there is a mutation in the T-cell receptor that inhibits antigens like CD8 and CD7, but stimulates the over production of other antigens like CD4. This mutation is a clonal gene rearrangement at the TCR-γ gene. Clonal gene rearrangements create novel or new surface antibodies during early differentiation.[1] Since these mutated antibodies are created early on, they are able to undergo mitosis and produce new T-cell lymphocytes that also contain the novel antigens. The abnormal quantity of T-cell receptors occurs because they are selected for since they express new qualities. CD4+ is the receptor that is selected for and increases in number in Lutzner cells. The neoplastic T-cells produce cytokines which active the expression of eosinophils and suppress the ability of T-cells to initiate an immune response. Since T-cell activity is lessened, the cells are not able to respond to invaders. Invaders are allowed to grow and produce lesions, and as the lesions increase in size the T-cell antigen is lost. Once this antigen is lost, the T-cell antibodies will never be able to detect the pathogen, allowing the pathogen to increase in size and cause an infection to occur.[5] This leads to the development of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma such as Mycosis Fungoides and Sézary Syndrome.

Types

The mutated cells are mature T-lymphocytes and contain CD4+ receptors on the membrane surface. There are two variants of this mutated cell, Lutzner cells and Sézary cells. Sometimes these names are interchangeable, but it has been determined through histology that they are morphologically different.

Lutzner cells

Lutzner cells are bigger than normal lymphocytes and contain extensive folding in their membrane. They are described at being cerebriform in shape, and can be diploid or tetraploid. It also contains a large nucleus with a minimum cytoplasm. Lutzner cells are more predominant in Mycosis Fungoides, but are also found in Sézary Syndrome.[6]

Sézary cells

Sézary cells are bigger than Lutzner cells, and have an overabundance of cellular folds in the membrane. They are also considered over pigmented and have a large nucleus with a small cytoplasm. Sézary cells are found in both Mycosis Fungoides and Sézary Syndrome.[7]

Diseases

Lymphoma

It is an unrare form of cancer that originates in the lymph system and causes the destructive effects in the immune system.[8] There are two types of lymphoma, Hodgkin’s lymphoma and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Both types of lymphomas form from a white blood cell or lymphocyte. Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma is the more common of the two cancers. The only way to tell these two forms of lymphoma apart is to perform a biopsy in order to get a microscopic view of the cancer cells. Hodgkin’s lymphoma involves the abnormal growth of undifferentiated lymphocytes, while non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma involves differentiated immune cells like B cells and T cells for example. Lutzner cells are involved with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.[9]

Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma

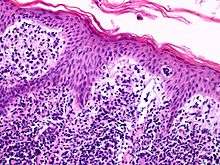

It is the most common type and diverse range of lymphoma. Normally, it occurs with a B cell becoming abnormal, but also occurs when a T cell becomes abnormal. The mutated cell then divides to create multiple cells. Lymphoma cells can be distributed all over the body and into various tissues.[9] Lutzner cells are found in skin tissue, more specifically, the epidermis and dermis layers. An accumulation of Lutzner cells in the layers of the skin can cause cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Cutaneous cell lymphoma is the second most common form of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.[10] Two forms of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma associated with abnormal T-lymphocytes or Lutzner cells are Mycosis Fungoides and Sézary Syndrome.[11] These two diseases are very similar, but both present themselves in different ways.

Mycosis Fungoides

_Mycosis_Fungoides_later_stage.jpg)

- Signs and Symptoms:

- 4 Phases:[11]

- Premycotic Phase: Scale-like red rash on areas of the skin that are not exposed to the sun.

- Patch Phase: An itchy, thin rash

- Plaque Phase: Raised bumps or lesions present on the skin

- Tumor Phase: Tumors begin to form on the skin near or under the lesions.

- 4 Stages

- 4 Phases:[11]

- Diagnosis:

- Physical exam to check for lesions

- Peripheral blood smear

- Use a microscope to count the number of blood cells and look at their shape.

- Skin biopsy

- Checks for signs of cancer

- Immunophenotyping

- Flow cytometry

- T-cell receptor gene rearrangement test[12]

- Liver Function Test

- HIV test

- X-ray, CT scan, and PET scan

- To determine if the lymphoma is metastatic

- Treatments:[13]

- Chemotherapy

- Radiation

- Drug Therapy

- Photodynamic Therapy

- Biologic Therapy using Interferon

- Targeted Therapy

- UV Radiation Therapy

- Clinical Trials being pursued

- Stem cell transplant combined with chemoradiation

- Clinical trials being pursued

Sézary Syndrome

- Signs and Symptoms

- Rough, red rash

- Lymphadenopathy

- Abnormal thickening of the palms of the hands and soles of the feet

- Hair loss of balding

- Nail trauma

- Ectropion

- Liver and Spleen become swollen

- 4 Stages (link)

- Diagnosis

- Physical exam to check for lesions

- Peripheral blood smear

- Use a microscope to count the number of blood cells and look at their shape.

- Skin biopsy

- Checks for signs of cancer

- Immunophenotyping

- Flow cytometry

- T-cell receptor gene rearrangement test[12]

- Liver Function test

- HIV test

- X-ray, CT scan, and PET scan

- To determine if the lymphoma is metastatic

- Treatments[1][13]

- Chemotherapy

- Radiation

- Drug Therapy

- Photodynamic Therapy

- Biologic Therapy using Interferon

- Targeted Therapy

- UV Radiation Therapy

- Clinical Trials being pursued

- Stem cell transplant combined with chemoradiation

- Clinical trials being pursued

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Kumar, V., & et al. (2014). Robbins & Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease, 9th Edition. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Elsevier Health Sciences.

- 1 2 3 4 Ehrlich, A., & Schroeder, C. (2008). Medical Terminology for Health Professions. Independence, Kentucky: Cengage Learning.

- ↑ Lutzner, M. A. (1985). History of 2 cells in T cell lymphomas and leukemias: the cerebriform Lutzner cell in Sézary syndrome and the polylobulated or polypetaloid cell in acute T cell lymphoma/leukemia. Hautarzt, 36(12). 657-662.

- 1 2 Streilein, J. W. (1978). Lymphocyte Traffic, T-cell Malignancies and the Skin. The Journal of Investigative Dermatology, 71(3). 167-171.

- ↑ Cyriac, M. J., & Kurian, A. (2004). Sézary cell. Indian Journal of Dermatology, Venereology, and Leprology, 70(5). 321-324.

- ↑ Braun-Falco, O., & et al. (2013). Dermatology. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Springer Science & Business.

- ↑ Leong, A., & et al. (2005). Diagnostic Lymph Node Pathology. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press.

- ↑ Lennert, K. (2012). Malignant Lymphomas Other than Hodgkin’s Disease: Histology, Cytology, Ultrastructure, Immunology. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Springer Science & Business.

- 1 2 Shankland, K. R., & et al. (2012). Non-Hodgkin lymphoma. The Lancet, 380(9844). 848-857.

- ↑ Willemze, R., & Dreyling, M. (2010). Primary cutaneous lymphomas: ESMO Clinical Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol, 21(5). 177-180.

- 1 2 Makdisi, J., & Friedman, A. (2013). Mycosis fungoides—an update on a non-mycotic disease. J Drugs Dermatol, 12(7). 825-831.

- 1 2 Xu, C., & et al. (2011). Diagnostic significance of TCR gene clonal rearrangement analysis in early mycosis fungoides. Chin J Cancer, 30(4), 264-272.

- 1 2 Mycosis Fungoides and the Sézary Syndrome Treatment. (2015, May 26). Retrieved November 20, 2015, from http://www.cancer.gov/types/lymphoma/patient/mycosis-fungoides-treatment-pdq.