Mahafaly

|

Mahafaly children | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 150,000 (2013) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Madagascar | |

| Languages | |

| Malagasy | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Malagasy groups; Austronesian peoples |

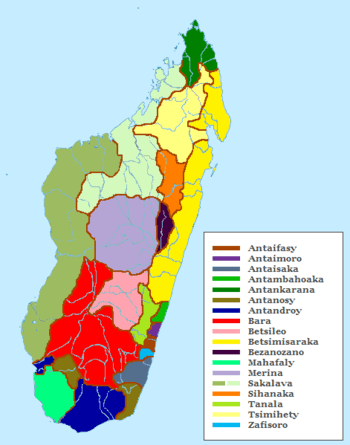

The Mahafaly are an ethnic group of Madagascar that inhabit the plains of the Betioky-Ampamihy area. Their name means either "those who make taboos" or "those who make happy", although the former is considered more likely by linguists. In 2013 there were an estimated 150,000 Mahafaly in Madagascar.[1] The Mahafaly are believed to have arrived in Madagascar from southeastern Africa around the 12th century. They became known for the large tombs they built to honor dead chiefs and kings. Mainly involved in farming and cattle raising, they speak a dialect of the Malagasy language, which is a branch of the Malayo-Polynesian language group. They inhabit the plains of the Betioky-Ampamihy area.

Ethnic identity

The Mahafaly are believed to have arrived in Madagascar from southeastern Africa around the 12th century and managed to preserve autonomy during the reign of the Merina kingdom. They inhabit the plains of the Betioky-Ampamihy area.[2][3]

Culture

The Mahafaly are mainly involved in farming and cattle raising.[4] They are known for the large tombs they build to honor dead chiefs and kings.[5] They are large stone squares surmounted by wooden sculptures and heaps of zebu horns; the greater the importance of the dead being buried, the greater the number of sculpture and horns placed on the tomb. The sculptures are termed aloalo, a word that implies the meaning "messenger" or "intermediary", possibly with reference to the interconnecting role they play between the worlds of the living and of the dead. One of the largest Mahafaly tombs is that of king Tsiampody, which is decorated with horns from over 700 zebus.[6]

Language

The Mahafaly speak a dialect of the Malagasy language, which is a branch of the Malayo-Polynesian language group derived from the Barito languages, spoken in southern Borneo.[7][8]

References

- ↑ Diagram Group 2013.

- ↑ Bradt & Austin 2007.

- ↑ Ogot 1992.

- ↑ LeHoullier, Sara (August 2010). Madagascar (Travel Companion). Other Places Publishing. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-9822619-5-8.

- ↑ Aloalo (tomb sculpture)

- ↑ Bradt, Hilary (2011). Madagascar. Bradt Travel Guides. p. 26. ISBN 978-1-84162-341-2.

- ↑ Shoup III, John A. (17 October 2011). Ethnic Groups of Africa and the Middle East: An Encyclopedia: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 180. ISBN 978-1-59884-363-7.

- ↑ International Encyclopedia of Linguistics: AAVE-Esperanto. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. 2003. p. 205. ISBN 978-0-19-513977-8.

Bibliography

- Bradt, Hilary; Austin, Daniel (2007). Madagascar (9th ed.). Guilford, CT: The Globe Pequot Press Inc. pp. 113–115. ISBN 1-84162-197-8.

- Diagram Group (2013). Encyclopedia of African Peoples. San Francisco, CA: Routledge. ISBN 9781135963415.

- Ogot, Bethwell A. (1992). Africa from the Sixteenth to the Eighteenth Century. Paris: UNESCO. ISBN 9789231017117.