The Mansion of Happiness

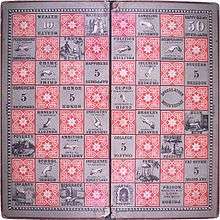

The Mansion of Happiness: An Instructive Moral and Entertaining Amusement is a children's board game inspired by Christian morality. Players race about a sixty-six space spiral track depicting virtues and vices with their goal being The Mansion of Happiness at track's end. Instructions upon virtue spaces advance players toward the goal while those upon vice spaces force them to retreat.

The Mansion Of Happiness was designed by George Fox,[1] a children's author and game designer in England. The first edition, printed in gold ink "containing real gold" using one copper plate engraving and black ink using a second copper plate engraving, produced a few hundred copies. Water coloring was used to complete the game board, making a brilliant, colorful, and expensive product fit for the nobility. Later in 1800, a second edition was printed, probably for rich but common folk. Only one copper plate was used to print black ink and no water coloring was used. The game must have become quite popular in England as a third edition was printed using two copper plates, one for black, and the second for green lines to indicate blank spaces. Water colors were added to make a beautiful product. Laurie and Whittle published all three editions in 1800. On all three editions George Fox was listed as the inventor and the game honored the Duchess of York. In the first edition, gold not only added color and price but homage to royalty. In all three editions, the paper was glued to linen so it could fold up and be inserted into a heavy attractively labeled cardboard case.

W. & S. B. Ives published the game in the United States in Salem, Massachusetts on November 24, 1843.[2] It was republished by Parker Brothers in 1894 after George S. Parker & Co. bought the rights to the Ives games. The republication claimed The Mansion of Happiness was the first board game published in the United States of America; today, however, the distinction is awarded to Lockwood's Traveller's Tour games of 1822.[3] The popularity of The Mansion of Happiness and similar moralistic board games was challenged in the last decades of the 19th century when the focus of games became materialistic and competitive capitalistic behavior.

Context

With the industrialization and urbanization of the United States in the early 19th century, the American middle class experienced an increase in leisure time.[4][5] The home gradually lost its traditional role as the center of economic production and became the locus of leisure activities and education under the supervision of mothers.[4] As a result, the demand increased for children's board games emphasizing literacy and Christian principles, morals, and values.[4] Advances in papermaking and printing technology during the era made the publication of inexpensive board games possible,[4] and the technological invention of chromolithography made colorful board games a welcome addition to the parlor tabletop.[5]

One of the earliest children's board games published in America was The Mansion of Happiness (1843), "the progenitor of American board games".[6] Like other children's games that followed in its wake, The Mansion of Happiness was based on the Puritan world view that Christian virtue and deeds were assurances of happiness and success in life.[5] Even game mechanics were influenced by the Puritan view.[4] A spinner or a top-like teetotum, for instance, was utilized in children's board games rather than dice, which were then associated with Satan and gambling.[4] While the Puritan view forbade game playing on the Sabbath, The Mansion of Happiness and similar games with high moral content would have been permitted for children in more liberal households.[7]

In 1860, Milton Bradley developed a radically different concept of success in The Checkered Game of Life, the first American board game rewarding players for worldly ventures such as attending college, being elected to Congress, and getting rich.[5] Virtue became a means to an end rather than an end in itself. Daily life was the focus of the game with secular virtues such as thrift, ambition, and neatness receiving more emphasis than religious virtues.[4] Indeed, the only suggestion of religion in Bradley's game was the marriage altar.[4] The Checkered Game of Life was wildly popular, selling 40,000 copies in its first year.[5]

Protestant America gradually began viewing the accumulation of material goods and the cultivation of wealth as signs of God's blessing,[4] and, with the decade of economic expansion and optimism in the 1880s, wealth became the defining characteristic of American success. Protestant values shifted from virtuous Christian living to values based on materialism and competitive, capitalist behavior. Being a good Christian and a successful capitalist were not incompatible.[4] Dice lost their taint during the period, and replaced teetotums in games.[5]

In a twist on The Mansion of Happiness, McLoughlin Brothers and Parker Brothers released several games in the late 1880s based on the then-popular Algeresque rags to riches theme.[6] Games such as Game of the District Messenger Boy, or Merit Rewarded, Messenger Boy, Game of the Telegraph Boy, and The Office Boy allowed players to emulate the successful capitalist.[4] Players began these games as company underlings, newbies, or gofers, and, with luck, won the game with a seat in the President's Office (rather than a seat in Heaven, as in The Mansion of Happiness) or as Head of the Firm.[5] In Parker Brothers' The Office Boy, spaces designating carelessness, inattentiveness, and dishonesty sent the player back on the track while spaces designating capability, earnestness, and honesty advanced him toward the goal.[6] Such games reflected the belief that the enterprising American – regardless of his background, humble or privileged – would be rewarded under the American capitalist system,[5] and insinuated that success was equated with increased social status via the accumulation of wealth.[4]

Wealth and goods became game rewards during the last decades of the 19th century with the winner of McLoughlin Brothers' The Game of Playing Department Store, for instance, being the player who carefully spent his money accumulating the most goods in a department store.[5] Bulls and Bears: The Great Wall St. Game promised players they would feel like "speculators, bankers, and brokers",[5] and the 1885 catalog advertisement for McLoughlin Brothers Monopolist informed the interested, "On this board the great struggle between Capital and Labor can be fought out to the satisfaction of all parties, and, if the players are successful, they can break the Monopolist and become Monopolists themselves".[5]

Game play

The Mansion of Happiness is a roll-and-move track board game, and, typical of such games, the object is to be the first player to reach the goal at the end of the board's track, here called The Mansion of Happiness (Heaven).[4] Centrally located on the board, the goal pictures happy men and women making music and dancing before a house and garden.[7] To reach The Mansion of Happiness, the player spins a teetotum and races around a sixty-six space spiral track depicting various virtues and vices.[4]

Instructions upon spaces depicting virtues move the player closer to The Mansion of Happiness while spaces depicting vices send the player back to the pillory, the House of Correction, or prison, and thus, further from The Mansion of Happiness.[7] Sabbath-breakers are sent to the whipping post.[7] The vice of Pride sends a player back to Humility, and the vice of Idleness to Poverty.[8] The game's rules noted:

"WHOEVER possesses PIETY, HONESTY, TEMPERANCE, GRATITUDE, PRUDENCE, TRUTH, CHASTITY, SINCERITY...is entitled to Advance six numbers toward the Mansion of Happiness. WHOEVER gets into a PASSION must be taken to the water and have a ducking to cool him... WHOEVER posses[ses] AUDACITY, CRUELTY, IMMODESTY, or INGRATITUDE, must return to his former situation till his turn comes to spin again, and not even think of HAPPINESS, much less partake of it."[4]

Design and publication

The Mansion of Happiness was published in many forms, first in England, then in the United States. It was designed by George Fox and published as a linen game board that folded into a hard cover booklet. Laurie and Whittles published three editions of the game in 1800,[1] and a Laurie relative published it in England again in 1851.[9]

It was first published in the United States by W. & S.B. Ives in Salem, Massachusetts on November 25, 1843.[2] Their game was a folding game board with a cloth and cardboard pocket attached to the bottom of the game board along its edge. In the pocket were the rules, implements, and teetotum. Its teetotum was an ivory dowel sharpened to a point at the bottom end inserted in an octagonal ivory plate. This type of teetotum was referred to as a pin and plate teetotum.

When board games were published in 1843, morality was the most important aspect of the game. Since dice were called "the bones of the Devil" because they were used to determine which Roman soldier would keep Christ's loin cloth, teetotums were used instead. There were many different printings of Ives' The Mansion of Happiness.

FIRST EDITION: The first two print runs used Thayer and Company lithograpers, with one litho stone for the color and the other for printing black on the white paper stock. Because the paper of 1840's through 1890's included a lavish amount of fiber, often taken from mummy wrappings, it would not fade or decompose like the wood pulp paper used today. The first print run copied the Laurie and Whittles game. Laurie and Whittles used gold ink. Thayer mixed his ink to look gold but it really was a goldish brown. Like Laurie and Whittles game, Thayer used an octagonal end space.

SECOND EDITION: In Thayer's second print run, in 1844, he used the same litho stones as used in the first edition. Green was used instead of goldish brown and the endspace remained an octagon. By September 24, 1844, between 3000 and 4000 of the Thayer printed games were sold by its publishers, W. &. S.B. Ives.[10]

THIRD EDITION: By the fall of 1844, Thayer left the lithography business and was replaced by John Bufford, a lithographer who worked for Thayer in Boston from 1939 through 1844. Previously, from 1835 through 1839, Bufford owned his own firm in New York under the title Bufford Lithographer. By the end of 1844 through 1851,[11] the Boston company name was changed to J. H. Bufford & Co.[12] The next, third edition, listed Bufford Lithographer[13] so the third edition must have been printed after the beginning of the fall of 1844 but before the end of 1844. J. H. Bufford & Co. printed other Ives' games but this third edition of Ives' The Mansion Of Happiness is the only Ives' game to list Bufford Lithographer. Green was again used on one of the litho stones but the end space was a green circle. The other litho stone printed black.[14]

FOURTH EDITION: Thayer then returned to his business in 1847. Ives needed another print run of The Mansion Of Happiness that year. So Thayer needed two new litho stones, resulting in the fourth edition.[14] Thayer again printed one color in black and one color in green and changed the endspace back to a green octagon.[14] The entire game board looked different from his first two print runs. Thayer's first and second edition litho stones were either no longer usable or ground down and redrawn for other lithographs. On the new "black printing" litho stone the position of "Thayer and Company Lithograpers" was moved. The new "green printing" litho stone not only included green printing for unnamed spaces but also for corner decorations and to highlight the beginning of the banner.[15][16][17]

FIFTH EDITION: Another Thayer edition was needed between 1847 and 1853, so splitting the difference results in 1850. We know this because the lithography is different from the 1847 edition. The "green printing" litho stone had apparently been damaged or over used so the green printing at the beginning of the banner was removed.[18]

SIXTH EDITION: Yet another Thayer printrun was needed in early 1853. Thayer was about to leave his Boston business for the final time, but finished the job for the Ives firm. This sixth edition resulted from another need to redraw the green printing litho stone. Green was removed from the banner and corners, and, only the blank spaces were printed in green.[9]

SEVENTH EDITION: When Thayer left, his brother-in-law, S. W. Chandler took over the business in late 1853.[14] so a seventh edition was needed by the beginning of 1854. Two new litho stones were made.[14] Chandler printed black using one stone and green with the other. The endspace was changed back to a green circle.[14] There are at least two known copies of the Chandler edition, one was owned by deceased game historian Lee Dennis. Another is owned by a charter member of The American Game Collectors Association.[19]

EIGHTH EDITION: William and Stephen Bradshaw Ives dissolved their partnership on April 24, 1854.[20] William then put most of his time managing his newspaper, The Salem Observer. Stephen Bradshaw held the copyrights for the games and started a fancy goods importing business in Boston while overseeing the Salem business owned by a partnership of his youngest son, Henry P. Ives, and Henry's partner, Augustus Smith at the same business location.[21] A new Mansion Of Happiness print run was needed but Chandler was no longer in business, With control of the copyright, the Ives family chose lithograper F.F. Oakleys. Consequently Ives and Smith could sell The Mansion Of Happiness in Salem but had no right to the copyright. F. F. Oakleys needed to two new litho stones so the eighth edition was created. One stone was used to print black and the other to print green. The circle endspace was retained.[22] In addition to continue publishing The Mansion of Happiness, H. P. Ives and A. A. Weeks published at least two new games: Experts[23] and Tournament & Knighthood.[24]

NINTH EDITION: By December 21, 1860, Henry P. Ives bought out A. A. Smith to obtain the business. A. A. Smith then partnered with G. M. Whipple to form another bookstore and publishing business where they published The Game of Authors.[25] Henry P. Ives continued to publish The Mansion of Happiness using other lithographers, including Taylor & Adams of Boston in 1864,[26] Henry P. Ives was free to publish The Mansion Of Happiness and other Ives' games under his name, his brother's name, and his father's name.

TENTH EDITION: In 1886, Henry P. Ives sold his remaining inventory to George S. Parker. George S. Parker reprinted the green cover label to read H. P. Ives, Geo. S. Parker & Co. and affixed this label to the back of the gameboard over the original H. P. Ives label.[27] By 1888, Henry P. Ives sold all the game rights of the Ives family to Geo. S. Parker & Co., part of them in 1887[28] and the rest of them in 1888.[29] The green printing and circle end space remained through different lithographers until 1886.

ELEVENTH EDITION: Parker Brothers published the eleventh edition in 1894.[30] They continued to print this 1894 edition well into the early 1900s.[22]

TWELFTH EDITION: McLoughlin Brothers of New York published their own edition in 1895,[31] using different lithographs from the 1894 Parker Brothers edition, both on the game box cover and game board.

THIRTEENTH EDITION: In 1926, Parker Brothers Inc. republished The Mansion of Happiness in its original form, with minor modification to game spaces. The game included the circular end space introduced by J. Bufford in the third edition. This sixth edition used a folding game board with a fabric and cardboard pocket on the back edge of the game board. The teetotum was made using a wood dowel and cardboard hexagon.[32]

Misconceptions

Anne Wales Abbot was believed to be the designer of the Ives' game, The Mansion of Happines for over 145 years, from 1843 to 1989. She, however, did not design Ives The Mansion of Happiness but did design two other Ives' games: Dr. Busby and Master Rodbury and His Pupils.[33]

As further proof, Anne Wales Abbot was busy designing The Game Of Racers for Crosby and Nichols of Boston, an Ives's competitor. According to The Salem Observer, The Game Of Racers went on sale in Salem, Massachusetts through J. P. Jewett on January 13, 1844.[34] It went on sale in Boston even earlier. Abbot would have been working with Crosby and Nichols in Boston while the Ives firm published The Mansion Of Happiness.

The Mansion of Happiness was considered the first mass-produced board game in the United States for almost 100 years. In 1886, George S. Parker purchased some of Ives' inventory from Henry P. Ives, who had taken over the Ives' business.[35] George had his own oversized green label printed and proceeded to glue it over the Ives label.[27] When the last of the Ives brothers died in 1888, board game titans Charles and George Parker purchased the rights to The Mansion of Happiness. In 1894, Parker Brothers republished The Mansion of Happiness in their new patented box. The game came with a cover on top of a box. The game board was attached to the top of the box and a drawer was added to the box for the implements and spinner. A teetotum was no longer needed as a metal pointer could be attached to a lithographed card using a pop rivet. The pointer could then spin around to produce a random number.[22] The game board and box top were printed using lithography, making the game look like a work of art. Some of the vice spaces were removed (those depicting women engaged in immoral acts and behaviors), and men were substituted for women in the House of Correction. The game remained in the Parker Brothers catalog for thirty years, displaying the line, "The first board game ever published in America" on its box cover.[6][36]

In 1895, the New York game firm of McLoughlin Brothers printed and published another version of The Mansion of Happiness.[22] The McLoughlin version used even better artwork than the Parker Brothers version which makes it more valuable to collectors. The McLoughlin version used a game box with the game board attached to the inside bottom of the box. Implements and spinner were simply placed in the box.

The distinction of "the first published American board game" however is awarded today to Traveller's Tour of the United States published by New York book sellers F. & R. Lockwood in 1822.[3][37][38] Because printing of game boards was more difficult in 1822 than 1843, the term mass market is a gray area. In 1822 reversed etched copper plates were used to print game boards. After the first 2,000 impressions, breaks quickly appeared in lines. Games were so expensive, the people who could afford them did not want game boards they could not read. By 1843, lithography with water color painting was popular. Lithography could easily produce 40,000 perfect impressions.

Legacy

With The Mansion Of Happiness published from 1800 in England to 1926 in The United States, it is the longest continuously published board game with a known designer, George Fox. That totals 126 years of continuous publication. Obviously Chess, Draughts (Checkers), Go, and many other board games have been continuously published for a longer time, but no one knows the designer of these games.

References

- 1 2 Angiolillo Collection: Laurie and Whittles, printed the designer on their The Mansion of Happiness game board, Laurie and Whittles Publishers, 1800.

- 1 2 The Salem Gazette page 3, column 5, November 24, 1843.

- 1 2 Angiolillo, Joseph A. Jr. Game Times number 15, American Game Collectors Association Publishers, August 1991.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Jensen, Jennifer. "Teaching Success Through Play: American Board And Table Games, 1840–1900". Magazine Antiques, December, 2001.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Hofer, Margaret K.. The Games We Played: the Golden Age of Board & Table Games. Princeton Architectural Press, 2003. ISBN 1-56898-397-2.

- 1 2 3 4 Orbanes, Philip E.. The Game Makers: The Story of Parker Brothers, from Tiddledy Winks to Trivial Pursuit. Harvard Business School Press, 14 November 2003. ISBN 1-59139-269-1; ISBN 978-1-59139-269-9.

- 1 2 3 4 Volo, James M., and Dorothy Denneen Volo. Family Life in 19th-century America. Greenwood Publishing Group, 2007. ISBN 0-313-33792-6 / ISBN 978-0-313-33792-5.

- ↑ The Journal of American Folk-Lore. Vol. VII, No. XXIV, January–March, 1894.

- 1 2 Angiolillo Collection: The Mansion of Happiness, No. 53 Fleet Street, London, published 1st September, 1851.

- ↑ The Salem Gazette page 3, column 5, November 24, 1844.

- ↑ Tatham, David. "John Henry Bufford: American Lithographer" Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society 86(1): 47-73. 1976

- ↑ G.B. Baumgardner (1986). "George and William Endicott: commercial lithography in New York, 1831-51". Prints and printmakers of New York State, 1825-1940.

- ↑ http://www.games2collect.com/Data/Compendium%20Items/Library/M/Mansion%20of%20happiness%201843%20WandSB%20Ives.html.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Essex Institute Newsletter vol. 13, no, 4

- ↑ http://www.giochidelloca.it/scheda.php?id=422

- ↑ http://www.thestrong.org/online-collections/nmop/3/48/78.412

- ↑ http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/treasures/images/at0107d_2bs.jpg

- ↑ The Dorchester Historical Society in Massachusetts owns a copy of this edition

- ↑ Angiolillo Collection: DVD showing the Chandler game in this second collection, video taken in 1986 by Joseph A. Angiolillo, Jr.

- ↑ The Salem Observer page 3, column 4, April 22, 1854

- ↑ The Salem Observer, page 3, column 4, December 23, 1845.

- 1 2 3 4 Angiolillo, Joseph A. Jr., Angiolillo Collection, On the game board front, "J. J. Oakleys & Co. Boston"

- ↑ The Salem Observer, page 3, column 3, January 2, 1858

- ↑ The Salem Observer, page 3, column 4, January 1, 1859

- ↑ The Salem Observer, page 3, column 3, December 21, 1860

- ↑ Angiolillo, Joseph A. Jr., Angiolillo Collection, On the game board front, "Taylor & Adams, Boston"

- 1 2 A copy of this game is owned by The Essex Institute which is part of the Peabody Museum in Salem, Mass.

- ↑ 1887 Geo. S. Parker & Co. Catalogue

- ↑ 1888 Geo. S. Parker & Co. Catalogue

- ↑ 1894 Parker Brothers Catalogue.

- ↑ The copyright on the box cover in the "Angiolillo Collection" is 1895.

- ↑ A copy of the republished game is owned by Joseph A. Angiolillo Jr. and it appears in the 1926 Parker Brothers, Inc. Catalogue

- ↑ Abbot, Anne Wales Dr. Busby and His Neighbors "A Story by the Author of Willie Rogers and The Games of Dr. Busby, Master Rodbury" printed on the title page, 1844.

- ↑ The Salem Observer, January 13, 1844 page 3 column 6.

- ↑ Geo. S. Parker & Co. Catalogue, page 3, 1886.

- ↑ Whitehill, Bruce. "A Brief History of American Games". Toy Shop, 1997.

- ↑ Van Dulken, Stephen. American Inventions: A History of Curious, Extraordinary, and Just Plain Useful Patents. NYU Press, 2004. ISBN 0-8147-8813-0 / ISBN 978-0-8147-8813-4.

- ↑ Rickards, Maurice, Twyman, Michael, De Beaumont, Sally, and Tanner, Amoret. The Encyclopedia of Ephemera: A Guide to the Fragmentary Documents of Everyday Life for the Collector, Curator, and Historian. Routledge, 2000. ISBN 0-415-92648-3 / ISBN 978-0-415-92648-5.