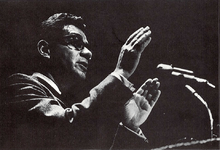

Mark Lane (author)

| Mark Lane | |

|---|---|

Mark Lane in Ann Arbor, 1967 | |

| Born |

February 24, 1927 The Bronx, New York, U.S.[1] |

| Died |

May 10, 2016 (aged 89) Charlottesville, Virginia, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Known for | Conspiracy theorist on the Assassination of John F. Kennedy |

Mark Lane (February 24, 1927 – May 10, 2016) was an American attorney, New York state legislator, civil rights activist, and Vietnam war-crimes investigator. He is best known as a leading researcher, author, and conspiracy theorist[2] on the assassination of U.S. President John F. Kennedy. From his 1966 number-one bestselling critique of the Warren Commission, Rush to Judgment,[3] to Last Word: My Indictment of the CIA in the Murder of JFK, published in 2011, Lane wrote at least four major works on the JFK assassination and no fewer than ten books overall.

Early career

Mark Lane was born in The Bronx, New York and raised in Brooklyn, New York. He served in the United States Army after World War II. After attending Long Island University, he received an LL.B from Brooklyn Law School in 1951.[4][5][6] As a law student, Lane was the administrative assistant to the National Lawyers Guild and orchestrated a fund-raising event at Town Hall in New York City that featured American folk singer Pete Seeger.

Following his admission to the New York bar in 1951, Lane established a practice with Seymour Ostrow in East Harlem. Although Lane acquired a reputation as "a defender of the poor and oppressed," Ostrow later asserted that Lane was "motivated more by his ambition and quest for publicity than any dedication to a cause or concern for the interest of his clients." The partnership dissolved in the late 1950s.[7]

In 1959, Lane helped found the Reform Democrat movement within the New York Democratic Party. He was elected with the support of Eleanor Roosevelt and presidential candidate John F. Kennedy (JFK) to the New York Legislature in 1960. During his own campaign, he also managed the New York City area's campaign for JFK's 1960 presidential bid.[8] He was a member of the New York State Assembly (New York County's 10th District, encompassing East Harlem and Yorkville, where Lane resided) in 1961 and 1962.[9] In the legislature, Lane spent considerable time working to abolish capital punishment. Lane promised to serve for only one term, and then manage the campaign for his replacement—which he did.

In June 1961, during the civil rights movement, Lane was the only sitting legislator to be arrested for opposing segregation as a "Freedom Rider".[10] In 1962, he ran for Congress in the Democratic primary and lost.[11] In the 1968 presidential election, Lane appeared on the ballot as a third party vice-presidential candidate, running on the Freedom and Peace Party ticket (an offshoot of the Peace and Freedom Party) with Dick Gregory.

Kennedy assassination

Four weeks after the assassination of Kennedy on November 22, 1963, Lane published an article in the National Guardian dealing in-depth with 15 questions regarding statements by public officials about the murders of J. D. Tippit and John F. Kennedy from the perspective of a defense attorney. The statements were about the witnesses who claimed to have seen Oswald on the sixth floor of the schoolbook depository; the paraffin test which, to Lane, indicated that Oswald had not fired a rifle recently; the conflicting claims about the rifle which at first was, as the police announced, a German Mauser and afterwards a World War II Mannlicher–Carcano; the Parkland Hospital doctors announcing an entrance wound in the throat, and the role of the FBI and the press, who convicted Oswald before his guilt was proven. In June 1964, according to historian Peter Knight, Bertrand Russell, "prompted by the emerging work of the lawyer Mark Lane in the US ... rallied support from other noteworthy and left-leaning compatriots to form a Who Killed Kennedy Committee, members of which included Michael Foot MP, the wife of Tony Benn MP, the publisher Victor Gollancz, the writers John Arden and J. B. Priestley, and the Oxford history professor Hugh Trevor-Roper." Russell published a highly critical article weeks before the Warren Commission Report was published, setting forth "16 Questions on the Assassination" and equating the Oswald case with the Dreyfus affair of late nineteenth-century France in which the state wrongly convicted an innocent man. Russell also criticized the American press for failing to heed any voices critical of the official version."[12]

Warren Commission

Lane applied to the Warren Commission to represent the interests of Lee Harvey Oswald, but the Commission rejected his request.[13] Three months later Walter E. Craig, president of the American Bar Association, was appointed by the Commission to represent the interests of Oswald. Craig himself stated that he was not counsel for Oswald; and official records do not indicate that Craig or his associates named, cross-examined, or interviewed witnesses of their own.[14] Lane continued to search for clues for Oswald's innocence. He was called to testify before the Commission but was not permitted to cross-examine witnesses. According to R. Andrew Kiel in J. Edgar Hoover: The Father of the Cold War, "After the Warren Commission's final report was completed in September 1964, Lane interviewed numerous witnesses ignored by the Commission."

Lane's testimony

Lane provided testimony to the Warren Commission in Washington, D.C. on March 4, 1964.[15] Lane testified that he had contacted witness Helen Markham sometime within the five days preceding his appearance before the Commission and that she had described Tippit's killer to him as "short, a little on the heavy side, and his hair was somewhat bushy".[16] He added, "I think it is fair to state that an accurate description of Oswald would be average height, quite slender with thin and receding hair."[16]

In addressing the assertion that Markham's description of Tippit's killer was not consistent with the appearance of Oswald, the Warren Commission stated that they had reviewed the telephone transcript in which she was alleged to have made it.[17][18] The Commission wrote: "A review of the complete transcript has satisfied the Commission that Mrs. Markham strongly reaffirmed her positive identification of Oswald and denied having described the killer as short, stocky and having bushy hair."[19]

Rush to Judgment

Lane published an indictment of the Warren Commission, entitled Rush to Judgment, using these interviews as well as evidence from the 26 volumes of the Commission's report. Despite the fact that the majority of Mark Lane's material for his book came from the Warren Report itself, as well as from interviews with those who were at the scene, sixteen publishers canceled contracts before Rush to Judgment was published."[14] The book became a number one best seller and spent 29 weeks on the New York Times best-seller list.[20] The book criticizes in detail the work and conclusions of the Warren Commission and remains one of the most remarkable books about the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. It was adapted into a documentary film in 1966.

Lane questions, among other things, the Warren Commission conclusion that three shots were fired from the Texas School Book Depository and focuses on the witnesses who had recounted seeing or hearing shots coming from the grassy knoll. Lane questions whether Oswald was guilty of the murder of policeman J.D. Tippit shortly after the Kennedy murder. Lane also states that none of the Warren Commission firearm experts were able to duplicate Oswald's shooting feat.[21]

According to former KGB officer Vasili Mitrokhin in his 1999 book The Sword and the Shield, the KGB helped finance Lane's research on Rush to Judgement without the author's knowledge.[22] The KGB allegedly used journalist Genrikh Borovik as a contact and provided Lane with $2000 for research and travel in 1964.[11][23] Mark Lane called the allegation "an outright lie" and wrote, "Neither the KGB nor any person or organization associated with it ever made any contribution to my work."[24]

Other books Lane wrote on the topic

Lane later wrote A Citizen's Dissent, documenting his response to the Warren Commission's governmental findings on the Kennedy assassination. He also wrote the first screenplay of the 1973 film Executive Action (starring Burt Lancaster and Robert Ryan), with Donald Freed, and was credited with supplying much of the research material for the film.[25] Lane asserted in his 1991 book Plausible Denial that he only worked on the first draft of the screenplay. He noted that he collaborated with Donald Freed on it and after seeing subsequent drafts, they complained both privately to the producer and publicly at press conferences, pointing out errors in the work.[26]

In 1991, Lane described Plausible Denial as his "last word" on the subject and told Patricia Holt of the San Francisco Chronicle: "I'll never write another sentence about the (JFK) assassination".[27] In November 2011, Lane published a third major book on the JFK assassination titled Last Word: My Indictment of the CIA in the Murder of JFK.[28]

Random House suit

In 1995, Lane lost a defamation suit against book publisher Random House who used the caption "Guilty of Misleading the American Public" under a photo of Lane in an advertisement for Gerald Posner's Case Closed.[2] He sought $10 million in damages for disparagement of his integrity and the unauthorized use of his photograph.[2] Lane was rebuked by Judge Royce C. Lamberth of the United States District Court for the District of Columbia who said: "A conspiracy theory warrior outfitted with Lane's acerbic tongue and pen should not expect immunity from an occasional, constrained chastisement."[2] A similar suit filed by Robert J. Groden against Random House was dismissed the previous year by a federal judge in New York.[29]

Vietnam War crimes investigations

In 1970, Lane involved himself in several war crime inquiries being conducted primarily by antiwar organizations such as the Citizens Commission of Inquiry (CCI) and the Vietnam Veterans Against the War. Lane used his contacts and raised funds to support these events, including what would become the CCIs National Veterans Inquiry and the VVAWs Winter Soldier Investigation. CCI and VVAW had originally combined their efforts toward the production of one large war crime investigation, and Lane was initially invited to join the organizing steering committee. Lane suggested the Winter Soldier name, based on Thomas Paine's description of the "summer soldiers" at Valley Forge shrinking from service to their country in a time of crisis. Lane would often travel with fellow activist Jane Fonda to antiwar speaking engagements and fundraising rallies. Lane was also writing a book, Conversations with Americans, a collection of interviews with US servicemen about war crimes in the Vietnam War.

Lane's close association with CCI and VVAW would be short-lived. Tod Ensign of the CCI recalled

It was a mistake to think that celebrities like Jane Fonda and Mark Lane who were used to operating as free agents would submit to the discipline of a steering committee. We should have placed them, instead, on an advisory panel where their visibility and political and money contacts would have been used without having to tangle with them on broader strategic and tactical questions.[30]

CCI staffers criticized Lane as being arrogant and sensationalistic, and said the book he was writing had "shoddy reporting in it". The CCI leaders refused to work with Lane further and gave the VVAW leaders a "Lane or us" ultimatum. VVAW did not wish to lose the monetary support of Lane and Fonda, so the CCI split from the project. The following month, after caustic reviews of Lane's book by authors and a Vietnam expert, VVAW also distanced itself from Lane.[31]

James Reston Jr., in the Saturday Review, calls Lane's book disreputable, in that all of the reports contained in it are admittedly unverified, and lean toward the salacious. "Lane makes no pretense of distinguishing between fact and a soldier's talent for embellishment", Reston observed. Commenting on the book's redeeming social value, Reston added that "it would be to show that a pattern of atrocities exists in Vietnam, proving that while My Lai was larger, it was not unique. This needs to be demonstrated, since the Pentagon continues to insist that My Lai was an isolated case. But the effort will have to be left to more responsible parties, like the National Veterans Inquiry."[32] A review of Lane's book by Neil Sheehan in the New York Times Book Review claimed that four of the 32 servicemen interviewed by Lane for the book had misrepresented their military service, according to the Defense Department. Lane responded to Sheehan’s inquiries by stating that the Defense Department is the least reliable of all sources for verification of atrocity accounts and that verification of simple facts about the interviewees was “not relevant.” Sheehan called Lane's book irresponsible, concluding that, "Some of the horror tales in this book are undoubtedly true", and the "men who now run the military establishment cannot conduct a credible investigation... But until the country does summon up the courage to convene a responsible inquiry, we probably deserve the Mark Lanes." [33] Because of Sheehan's review, Simon and Schuster reneged on the contract for the book. When Lane disproved Sheehan's charges, they were forced to settle with him.[34]

The controversial book reviews caused concern in the VVAW leadership, as Andrew E. Hunt notes,

Sheehan's exposé had placed VVAW leaders in a difficult position. Lane's involvement with the planning of the Winter Soldier Investigation had been extensive. His legal and financial assistance had proven invaluable. Few VVAWers doubted his sincerity or devotion to the effort. Yet they feared associating with Lane could tarnish months of difficult work. "Then the question became, 'How do we protect our integrity?'" recalled Joe Urgo, "'How do we separate ourselves from this guy?'" Organizers hoped Lane would maintain a low profile. Their wishes were fulfilled.[35]

VVAW veterans involved with the WSI event then realized they needed to take control, and insisted that there be no more interference from the likes of Lane. A new, all-veteran steering committee was formed without Lane. Ultimately, the WSI was an event produced by veterans only, without the need of civilians such as Lane and Fonda.[36]

Martin Luther King assassination

Lane wrote Murder In Memphis with Dick Gregory (previously titled Code Name Zorro, after the Central Intelligence Agency's name for King) about the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., in which he alleged a conspiracy and government coverup.[37] Lane represented James Earl Ray, King's alleged assassin, before the House Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA) inquiry in 1978. The HSCA said of Lane in its report, "Many of the allegations of conspiracy that the committee investigated were first raised by Mark Lane ...

Peoples Temple

Engagement and work for the Peoples Temple

In 1978, Lane began to represent the Peoples Temple. Temple leader Jim Jones hired Lane and Donald Freed to help make the case of what it alleged to be a "grand conspiracy" by intelligence agencies against the Peoples Temple. Jones told Lane he wanted to "pull an Eldridge Cleaver", referring to the fugitive Black Panther who was able to return to the United States after repairing his reputation.[38]:440

In September 1978, Lane visited Jonestown, spoke to Jonestown residents, provided support for the theory that intelligence agencies conspired against Jonestown and drew parallels between Martin Luther King and Jim Jones. Lane then held press conferences stating that "none of the charges" against the Temple "are accurate or true" and that there was a "massive conspiracy" against the Temple by "intelligence organizations," naming the CIA, FBI, FCC and the U.S. Post Office. Though Lane represented himself as disinterested, the Temple paid Lane $6,000 per month to help generate such theories.[38]:440–441 Regarding the effect of the work of Lane and Freed upon Temple members, Temple member Annie Moore wrote that "Mom and Dad have probably shown you the latest about the conspiracy information that Mark Lane, the famous attorney in the ML King case and Don Freed the other famous author in the Kennedy case have come up with regarding activities planned against us—Peoples Temple."[39]:282 Another Temple member, Carolyn Layton, wrote that Don Freed told them that "anything this drug out could be nothing less than conspiracy".[39]:272

Jonestown tragedy

Lane was present in Jonestown during the evening of November 18, 1978, and witnessed or heard part of the events claiming at least 408 lives (out of a total recount of 915 carried out five days later); these events involved, up to some extent, murder-suicide by cyanide poisoning and were compounded by the murder of Congressman Leo Ryan and four others at a nearby airstrip.[40] For months before that tragedy, Jones frequently created fear among members by stating that the CIA and other intelligence agencies were conspiring with "capitalist pigs" to destroy Jonestown and harm its members.[41] This included mentions of CIA involvement in the address Jones gave the day before the arrival of Congressman Ryan.[42]

During the visit of Congressman Ryan, Lane helped represent the Temple along with its other attorney, Charles R. Garry, who was furious with Lane for holding numerous press conferences and alleging the existence of conspiracies against the Peoples Temple.[43] Garry was also displeased with Lane for making a veiled threat that the Temple might move to the Soviet Union in a letter to Congressman Ryan.[44]

Late in the afternoon of November 18, two men wielding rifles approached Lane and Garry, who had earlier been sent to a small wooden house by Jones.[45] It is not clear whether the gunmen were sent to kill Lane and Garry, but one of the gunmen recognized Charles Garry as an attorney in a trial that the gunman had attended.[45] After a relatively friendly exchange, the men informed Garry and Lane that they were going to "commit revolutionary suicide" to "expose this racist and fascist society".[45] The gunmen then gave Garry and Lane directions to exit Jonestown.[45] Garry and Lane then sneaked into the jungle, where they hid and called a temporary truce while the tragedy unfolded.[46]

On a tape made while members committed suicide by ingesting cyanide-poisoned punch, the reason given by Jones to commit suicide was consistent with Jones's previously stated conspiracy theories of intelligence organizations allegedly conspiring against the Temple, that men would "parachute in here on us", "shoot some of our innocent babies" and "they'll torture our children, they'll torture some of our people here, they'll torture our seniors".[47] Parroting Jones's prior statements that hostile forces would convert captured children to fascism, one temple member states, "[T]he ones that they take captured, they're gonna just let them grow up and be dummies".[47] Annie Moore and Carolyn Layton were among the 900 who died.

After the tragedy

Lane later wrote a book about the tragedy, The Strongest Poison.[48] Lane reported hearing automatic weapon fire, and presumes that U.S. forces killed Jonestown survivors.[49] While Lane blames Jones and Peoples Temple leadership for the deaths at Jonestown, he also claims that U.S. officials exacerbated the possibility of violence by employing agents provocateurs.[49] For example, Lane claimed that Temple attorney (and later defector) Timothy Stoen, who, Lane alleged, had repeatedly prompted the Temple to take radical action before defecting, "had evidently led three lives", one of those being a government informant or agent.[50]

Later career and death

Lane is the author of the book Arcadia in which he details the effort to prove that James Richardson, a black migrant worker in Florida, had been falsely accused of killing his seven children by unlawful actions on the part of the authorities involved. Richardson had been on death row for the crime, but after the book was published he received a new trial in which he was found not guilty. Richardson was released from prison after 21 years, and Richardson's babysitter later confessed to the murders.[51]

Lane represented the political advocacy group Liberty Lobby as an attorney when the group was sued over an article in The Spotlight newspaper implicating E. Howard Hunt in the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. Hunt sued for defamation and won a substantial settlement. Lane successfully got this judgment reversed on appeal. This case became the basis for Lane's book Plausible Denial. In the book, Lane claimed that he convinced the jury that Hunt was involved in the JFK assassination, but mainstream news accounts asserted that some jurors decided the case on the issue of whether The Spotlight had acted with "actual malice".[52] Lane represented Willis Carto after Carto lost control of the Institute for Historical Review in 1993.[53]

Lane resided in Charlottesville, Virginia.[54] He continued to practice law and lectured on many subjects, especially the importance of the United States Constitution (mainly the Bill Of Rights and the First Amendment) and civil rights.

At the annual Law Library of Congress and American Bar Association Law Day symposium 2001, on the question, "Who are the paradigms for the lawyer as reformer in American culture?", Mark Lane was one of the twelve legal figures featured by panel moderator, Bernard Hibbitts, professor at the University of Pittsburgh School of Law.[55]

On May 10, 2016, Lane died of a heart attack at his home in Charlottesville at the age of 89.[56]

Works

- Rush to Judgment. Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1966.

- 2nd Edition: Thunder's Mouth Press, 1992, ISBN 978-1-56025-043-2.

- A Citizen's Dissent: Mark Lane Replies to the Defenders of the Warren Report. Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1968.

- Chicago Eyewitness. Astor-Honor, 1968.

- Arcadia. Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1970, ISBN 978-0-03-081854-7.

- Conversations with Americans: Testimony from 32 Vietnam Veterans. Simon & Schuster, 1970, ISBN 978-0-671-20768-7.

- Code Name Zorro. Pocket, 1978, ISBN 978-0-671-81167-9 (with Dick Gregory).

- Reissued as: Murder in Memphis: The FBI and the Assassination of Martin Luther King. Thunder's Mouth Press, 1993, ISBN 978-1-56025-056-2.

- The Strongest Poison, Hawthorne Books, 1980, ISBN 0-8015-3206-X.

- Plausible Denial: Was the CIA Involved in the Assassination of JFK? Thunder's Mouth Press, 1991, ISBN 978-1-56025-000-5.

- Last Word: My Indictment of the CIA in the Murder of JFK. Skyhorse Publishing, 2011, ISBN 978-1-61608-428-8.

- Citizen Lane: Defending our Rights in the Courts, the Capitol, and the Streets, Laurence Hill Books, 2012, ISBN 978-1-61374-001-9.

Sources

- Bugliosi, Vincent. Reclaiming History: The Assassination of President John F. Kennedy. 2007, Norton, ISBN 978-0-393-04525-3.

- Kiel, R. Andrew. J. Edgar Hoover. The Father of the Cold War. How His Obsession with Communism Led to the Warren Commission Coverup and Escalation of the Vietnam War, 2000, University Press of America, Lanham MD, ISBN 978-0-7618-1762-8.

References

- ↑ "Citizen Lane", Chapter 1, Page 1

- 1 2 3 4 Rosenthal, Harry F. (January 26, 1995). "Judge Rebukes Conspiracy Theorist Mark Lane". Associated Press. AP. Retrieved February 28, 2013.

- ↑ name=Hawes Publications | url=http://www.hawes.com/1966/1966-12-25.pdf, p.2

- ↑ http://spectatorarchive.library.columbia.edu/cgi-bin/columbia?a=d&d=cs19620305-01.2.11

- ↑ "Mark Lane". Retrieved May 13, 2016.

- ↑ 'Mark Lane, gadfly lawyer, author, who promoted JFK conspiracy theory, dies at 89,' The Washington Post, Matt Schudel, May 14, 2016

- ↑ "Ocala Star-Banner - Google News Archive Search". Retrieved May 13, 2016.

- ↑ Citizen Lane: Defending Our Rights in the Courts, the Capitol, and the Streets; Mark Lane; Chicago Review Press; 2011. pp. 113–115

- ↑ Mark Lane. "CITIZEN LANE". Kirkus Reviews. Retrieved May 13, 2016.

- ↑ Bugliosi, p. 1011

- 1 2 Bugliosi, p. 1001

- ↑ Peter Knight, The Kennedy Assassination, Edinburgh University Press Ltd., 2007, p. 77. Also see "External Links": "Sixteen Questions on the Assassination (of President Kennedy).

- ↑ Kiel, p. 162.

- 1 2 Kiel, pp. 161–3.

- ↑ "Testimony of Mark Lane". Hearings Before the President's Commission on the Assassination of President John F. Kennedy, Volume II. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office. 1964. pp. 32–60.

- 1 2 Hearings Before the President's Commission on the Assassination of President John F. Kennedy, Volume II 1964, p. 51.

- ↑ "Chapter 4: The Assassin". Report of the President's Commission on the Assassination of President John F. Kennedy. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office. 1964. p. 167.

- ↑ "Appendix 12: Speculations and Rumors". Report of the President's Commission on the Assassination of President John F. Kennedy. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office. 1964. p. 652.

- ↑ Report of the President's Commission on the Assassination of President John F. Kennedy, Chapter 4 1964, p. 167.

- ↑ name=Hawes Publications | url=http://www.hawes.com/1966/1966-09-11.pdf, p.2 | url=http://www.hawes.com/1967/1967-03-26.pdf

- ↑ Bugliosi, p. 1005

- ↑ Persico, Joseph E. (October 31, 1999). "Secrets From the Lubyanka: A historian examines an archive of Soviet files smuggled to the West by a former K.G.B. agent". The New York Times. New York. Retrieved March 31, 2013.

- ↑ Christopher Andrew and Vasili Mitrokhin, The Sword and the Shield: The Mitrokhin Archive and the Secret History of the KGB, Basic Books, 1999. Excerpted here. According to the book, Soviet journalists, including KGB agent Genrikh Borovik, met with Mark Lane to encourage him in his research.

- ↑ Letter to The Nation from Lane

- ↑ Farber, Stephen (June 13, 1979). "Kennedy assassination subject of film". The Miami News. Miami. p. 4B. Retrieved May 26, 2013.

- ↑ Plausible Denial, Thunder's Mouth Press copyright 1991 page 326

- ↑ Holt, Patricia (December 31, 1991). "Mark Lane's Hunt For JFK Assassins" (PDF). San Francisco Chronicle. San Francisco. Retrieved May 4, 2015.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on December 8, 2015. Retrieved 2015-12-03.

- ↑ "Random prevails in suit over 'Case Closed' ad". Publishers Weekly. 241 (38): 9. September 19, 1994.

- ↑ Tod Ensign; Viet Nam Generation: A Journal of Recent History and Contemporary Issues, March 1994

- ↑ Hunt, Andrew E. (1999). The Turning: A History of Vietnam Veterans Against the War. New York University Press. pp. 63, 67. ISBN 978-0-8147-3635-7. Retrieved June 29, 2011. Lay summary.

- ↑ James Reston Jr., Saturday Review, January 9, 1971, p. 26

- ↑ New York Times Book Review, December 27, 1970 by Neil Sheehan

- ↑ Mark Lane; Citizen Lane, Chicago Review Press, 2012,218–220.

- ↑ Andrew E. Hunt; The Turning: A History of Vietnam Veterans Against the War; New York University Press, 1999; p. 67

- ↑ Gerald Nicosia; Home to War: A History of the Vietnam Veterans' Movement, 2001, p. 84

- ↑ Bugliosi, p. 1002

- 1 2 Reiterman, Tim (1982). Raven: The Untold Story of The Rev. Jim Jones and His People. ISBN 0-525-24136-1.

- 1 2 Moore, Rebecca. A Sympathetic History of Jonestown. Lewiston: E. Mellen Press. ISBN 0-88946-860-5

- ↑ Reiterman 1982, p. 484.

- ↑ See, e.g., Jim Jones, Transcript of Recovered FBI tape Q 234, Q 322, Q 051

- ↑ Jim Jones, Transcript of Recovered FBI tape Q 050

- ↑ Reiterman 1982, p. 460.

- ↑ Reiterman 1982, p. 461.

- 1 2 3 4 Reiterman 1982, p. 541.

- ↑ Tim Reiterman (1982) "Raven: The Untold Story of The Rev. Jim Jones and His People" ISBN 0-525-24136-1, p. 563

- 1 2 "Jonestown Audiotape Primary Project" Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. San Diego State University.

- ↑ Lane, Mark, The Strongest Poison, Hawthorne Books, 1980, ISBN 0-8015-3206-X

- 1 2 Moore, Rebecca, "Reconstructing Reality: Conspiracy Theories About Jonestown", Journal of Popular Culture 36, no. 2 (Fall 2002): pp. 200–20

- ↑ Lane, Mark, The Strongest Poison, Hawthorne Books, 1980, ISBN 0-8015-3206-X, p. 290

- ↑ "A Man Who Loves Challenges". Retrieved November 30, 2013.

- ↑ "Plausible Denial, Mark Lane, E. Howard Hunt, and the Liberty Lobby Trial". Retrieved May 13, 2016.

- ↑ Berlet, Cip; Lyons, Matthew M. (2000). "9 The Pillars of U.S. Populist Conspiracism; The John Birch Society and the Liberty Lobby". Right-wing Populism in America: Too Close for Comfort. New York: Guilford Press. p. 191. ISBN 9781572305625. Retrieved September 10, 2014.

- ↑ "Rushing to judgment-- and everywhere". The Hook. November 23, 2006. Retrieved December 9, 2006.

- ↑ "Law Day 2001 (June 2001) - Library of Congress Information Bulletin". Retrieved May 13, 2016.

- ↑ Schneider, Keith (May 13, 2016). "Mark Lane, Early Kennedy Assassination Conspiracy Theorist, Dies at 89". The New York Times. p. B14. Retrieved May 22, 2016.

External links

| New York Assembly | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Martin J. Kelly, Jr. |

New York State Assembly New York County, 10th District 1961–1962 |

Succeeded by Carlos M. Rios |