Marta Matamoros

| Marta Matamoros | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Born |

Marta Matamoros Figueroa 17 February 1909 Santa Ana neighborhood of Panama City, Panama |

| Died |

28 December 2005 (aged 96) Santa Ana, Panama City, Panama |

| Nationality | Panamanian |

| Occupation | dress maker, labor activist |

| Years active | 1920s-1970s |

| Known for | Attaining maternity leave legislation and the first minimum wage laws in Panama |

Marta Matamoros (1909-2005) was one of the labor leaders of Panama. In Panamanian history, she is known as a shoemaker, seamstress, trade unionist, communist and nationalist leader and is "synonymous with organized labor" in the Panamanian psyche. She is known for leading strikes in the 1940s which resulted in workers gaining maternity leave with pay and job security while they were on leave. In 1951, she became the first woman general secretary of the Trade Union Federation of Workers of Panama. "The Hunger and Desperation March" Matamoros led in 1959, resulted in the first minimum wage law in Panama. After she joined the Communist movement of Panama, she became the subject of investigations, though it did not stop her from protesting U.S. involvement in Panamanian affairs. In 1994, she was awarded the Grand Cross of the Order of Omar Torrijos Herrera and in 2006, a meritorious order was named in her honor, the Order of Marta Matamoros to recognize those who have promoted gender equality in Panama.

Biography

Marta Matamoros Figueroa was born on 17 February 1909 in the Santa Ana neighborhood of Panama City, Panama[1] to Josefa Figueroa and Gonzálo Matamoros.[2] Her father was a professional musician and had come to play in Panama City with the Banda de Batallón Colombia.[3] Both of her parents were from the border area between Costa Rica and Panama, known as the Coto Region.[4] Because it was unclear at that time whether the area belonged to Costa Rica or Panama,[5] when the Coto War broke out, the family were forced to flee back to Panama City. Her father's nationalism and humanitarianism became guiding spirits for Matamoros' life.[4]

Career

Forced to stop high school for lack of funding, Matamoros began working as a shoemaker and then became a dressmaker.[3] In 1941, she started working in the El Corte Inglés factory and came into contact with the harsh conditions under which laborers worked.[2][3] Seventy percent of the textile manufacturer's work force were women, swing in small cramped cubicles. The women labored for 12 to 13 hours per day and were paid between $5 and $7 per week. Comparably, men were paid $15 to $20 per week. There was no type of maternity leave, so if a worker became pregnant, they had to work up to their delivery and return promptly, or face losing their job.[3]

In 1945, Matamoros joined the Union of Tailors and Allied Workers of Panama (Spanish: Sindicato de Sastres y Similares de Panamá) and quickly worked her way through the ranks to become secretary of finance for the organization. By 1946, aware of labor developments in the region, Matamoros led a strike for the dressmakers of the Bazar Francés. Though the strike lasted only 38 days, was declared illegal and the workers, including Matamoros were fired, the women had succeeded in bringing attention to their need for better pay and working conditions. Esther Neira de Calvo and Gumercinda Páez, the first two women to serve in the National Assembly, agreed to take up the issue.[3] Matamoro's strike resulted in workers gaining paid maternity leave with pay and job security while they were on leave. It also ensured that they have job security for one year after their child's birth,[6] when the Labor Code was changed in 1947.[4]

Later that same year Matamoros led groups in protest of the Filós-Hines Convenant,[6] which attempted to extend World War II concessions for United States Military Bases in Panama to permanent status.[7] In 1951, she became the first woman general secretary of the Trade Union Federation of Workers of Panama (Spanish: Federación Sindical de Trabajadores de Panamá)[6] and was involved in protests against the United Fruit Company, which called for better working conditions and pay.[8] She served as the Union's delegate to the World Federation of Trade Unions (WFTU) Congress held in Vienna in 1953.[4] In the 1950s, Matamoros began studying the works of Marx and Lenin, traveling to the Soviet Union to see first-hand the gains made by workers there. She joined the People's Party of Panama[1] and served on its Central Committee.[3] She was arrested in 1951 and spent 99 days in the Modelo Prison for supporting a strike of bus drivers from Río Abajo, who were demanding salary and social insurance reforms.[1][9]

The McCarthyism which existed in the 1950s, led to job insecurity for Matamoros and she had to quit her factory employment. Instead she turned her focus to working independently and union organization.[3] In 1959, Matamoros led the strike called "The Hunger and Desperation March" (Spanish: Marcha del Hambre y la Desesperación),[3][10] in which protesters walked from Colón to Panama City in protest of high unemployment and inflation. The march was successful in establishing the first minimum wage law in the country and a new renter’s law.[11] She led protests against the U.S. Army intervention of the riots of 9 January 1964 and protests in 1967 against the Robles-Johnson Treaty,[3] which would have returned sovereignty of the Panama Canal Zone to Panama but allowed U.S. troops to remain in perpetuity.[12]

Matamoros never married or had children because she realized that marriage would have required her to give up her autonomy and ability to take risks. She founded many organizations to help women, including the Alliance of Panamanian Women (Spanish: Alianza de Mujeres Panameñas), the Vanguard of Women (Spanish: Vanguardia de Mujeres), the Women's Commission for the Defense of the Rights of Women and Children (Spanish: Comisión Femenina por Defensa de los Derechos de la Mujer y el Niño) and the National Union of Panamanian Women (Spanish: Unión Nacional de Mujeres Panameñas).[3]

Death and legacy

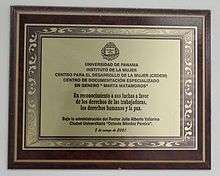

Matamoros died on 28 December 2005[1] in her apartment in Santa Ana[2] and has become, along with Domingo Barría and Angel Gómez, "synonymous with organized labor" in the Panamanian psyche.[13] In 1994, she was awarded the Grand Cross of the Order of Omar Torrijos Herrera.[1][14] She was honored by the University of Panama as one of the 100 outstanding women of Panama during the centennial celebration of Panama and the Institute for Women of the university is named in her honor. The Library of the National Confederation of Workers of Panama bears her name, as does a conference room in the Ministry of Labor and Workforce Development.[1] In 2006, an executive decree created the Order of Marta Matamoros to honor women who have been role models and strengthened the nation by working for socio-economic, political or cultural aims to improve gender equality of society.[1][15]

References

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Graell 2016.

- 1 2 3 Moreno Serrano 2005.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Guardia 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 EnCaribe 2013.

- ↑ De La Pedraja 2006, pp. 93-94.

- 1 2 3 Sotillo 2016.

- ↑ Ospina 2001, p. 252.

- ↑ The Panama American 1951, p. 1.

- ↑ Castillero Calvo & Miró 2003, p. 251.

- ↑ The Panama American 1959, p. 1.

- ↑ Collazos 1991, p. 55.

- ↑ Soler Torrijos 2008, p. 129.

- ↑ Alexander & Parker 2008, p. 14.

- ↑ Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores de Panamá 1995, p. 83.

- ↑ Official Panamanian Gazette 2006.

Bibliography

- Alexander, Robert Jackson; Parker, Eldon M. (2008). A History of Organized Labor in Panama and Central America. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger/Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-275-97740-5.

- Castillero Calvo, Alfredo; Miró, Rodrigo (2003). Panamá: itinerario de una nación, 1903-2003: en conmemoración del centenario de la república (in Spanish). Panamá: Hombre de la Mancha. ISBN 978-9962-8850-1-6.

- Collazos, Sharon Phillipps (1991). Labor and politics in Panama: the Torrijos years. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press. ISBN 978-0-8133-8115-2.

- De La Pedraja, René (2006). Wars of Latin America, 1899-1941. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-2579-2.

- Graell, Eric (16 February 2016). "Natalicio de Marta Matamoros" [The Birth of Marta Matamoros]. Farmacia Hoy el Periódico Digital (Pharmacy Today Digital Newspaper) (in Spanish). Ciudad de Panamá, Panamá: Sindicato de Trabajadores de Farmacias y Similares (Union of Pharmacy and Allied Workers). Archived from the original on 6 May 2016. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- Guardia, Mónica (17 April 2016). "Marta Matamoros, mujer de una sola pieza" [Marta Matamoros, woman of one piece] (in Spanish). Panama City, Panama: La Estrella de Panamá. Archived from the original on 7 September 2016. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores de Panamá (1995). Informe que presenta el Ministro de Relaciones Exteriores a la Asamblea Legislativa (in Spanish). Ciudad dePanamá, Panamá: National government publication.

- Moreno Serrano, Celia (2005). "Marta Matamoros (1909 - 2005)". Só Biografias (Only Biographies) (in Portuguese/Spanish). Campina Grande, Paraíba, Brasil: Universidade Federal de Campina Grande (Federal University of Campina Grande). Archived from the original on 24 April 2008. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- Ospina, Cristóbal (2001). Panamá, el país. translator: Marisa Arango (1 ed.). Panama: Ediciones Gamma. ISBN 978-958-9308-92-9.

- Soler Torrijos, Giancarlo (2008). In the Shadow of the United States: Democracy and Regional Order in the Latin Caribbean. Boca Raton, Florida: Brown Walker Press. ISBN 978-1-59942-439-2.

- Sotillo, Irlanda (20 March 2016). "Buscan sucesora de la medalla Marta Matamoros 2016" [Seeking successor for the 2016 Marta Matamoros Medal] (in Spanish). Panama City, Panama: La Prensa. Archived from the original on 30 May 2016. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- "Desperation March From Colon Branded As Communist Led". Panama City, Panama: The Panama American. 28 September 1959. Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- "Manifesto Assails US Money in RP". Panama City, Panama: The Panama American. 1 May 1951. Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- "Marta Matamoros". EnCaribe (in Spanish). Santo Domingo, República Dominicana: Enciclopedia de Historia y Cultura del Caribe EnCaribe (The Encyclopedia of History and Culture of the Caribbean). 2013. Archived from the original on 24 February 2014. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- "Ministerio de Desarrollo Social Decreto Ejecutivo No 81" [Ministry of Social Development Executive Decree No 81] (in Spanish) (25,554). Panama City, Panama: Gaceta Oficial de Panamá. 29 May 2006. Retrieved 8 September 2016.