Melaleuca viridiflora

| Broad-leaved paperbark | |

|---|---|

| |

| M. viridoflora near Canal Creek, Queensland | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| (unranked): | Angiosperms |

| (unranked): | Eudicots |

| (unranked): | Rosids |

| Order: | Myrtales |

| Family: | Myrtaceae |

| Genus: | Melaleuca |

| Species: | M. viridiflora |

| Binomial name | |

| Melaleuca viridiflora Sol. ex Gaertn. | |

Melaleuca viridiflora, commonly known as broad-leaved paperbark is a plant in the myrtle family, Myrtaceae and is native to woodlands, swamps and streams of monsoonal areas of northern Australia and New Guinea. It is usually a small tree with an open canopy, papery bark and spikes of cream, yellow, green or red flowers.

Description

Melaleuca viridiflora is a shrub or small tree usually growing to 10 m (30 ft) tall, sometimes twice that height, with white, brownish or grey bark and an open canopy. Its leaves are 70–195 mm (3–8 in) long, 19–76 mm (0.7–3 in) wide, thick, broadly elliptic and aromatic.[1][2][3][4]

The flowers are cream, yellow, yellow-green or occasionally red and arranged in spikes on the ends of branch which continue to grow after flowering and sometimes also in the upper leaf axils. Each spike contains 8 to 25 groups of flowers in threes and is up to 100 mm (4 in) long and 55 mm (2 in) in diameter. The petals are 4–5.3 mm (0.16–0.21 in) long and fall off as the flower matures. There are five bundles of stamens around the flower, each with 6 or 9 stamens although the stamens are only weakly joined in bundles. Flowering can occur at any time of the year but most commonly happens in winter. Flowering is followed by fruit which are woody capsules 5–6 mm (0.20–0.24 in) long, scattered along the stem, each containing numerous fine seeds.[1][2][3][4]

Taxonomy and naming

Melaleuca viridiflora was first formally described in 1788 by Daniel Solander, the description published by Joseph Gaertner in De fructibus et seminibus plantarum[5][6] including a carefully drawn figure of the stamen bundle and fruiting capsules.[7] The description was made during the forced stay of the Endeavour on the banks of the Endeavour River, at the site of the present-day Cooktown, during the first voyage of James Cook.[8] The specific epithet (viridiflora) is from the Latin viridis meaning "green",[9] and flos meaning "flower"[10] referring to the most common flower colour of this species.[1]

Distribution and habitat

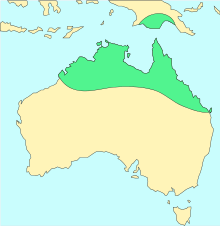

This melaleuca occurs in tropical areas of Australia, including as far south as Maryborough in Queensland, northern parts of Western Australia south to the Dampier Peninsula district, and the northern half of the Northern Territory. It is also found in the southern part of West Papua in Indonesia and southern Papua New Guinea[1][3] It grows on the margins of gallery forest, in forest, woodland and swampy plains in a variety of soils.[1]

Ecology

Melaleuca viridiflora forests provide habitat for orchid species including the rare, threatened or endangered Calochilus psednus, Pachystoma pubescens, Eulophia bicallosa and Cardwell midge orchid (Genoplesium tectum). Individual trees often host the epiphytic ant-house plant, (Myrmecodia beccarii).[11]

Plants distributed in south-eastern Florida in 1900 under the name Melaleuca viridiflora have been subsequently identified as Melaleuca quinquenervia.[12]

Uses

Traditional uses

Melaleuca viridiflora is used by Aboriginal Australians for multiple uses. The bark is peeled off in layers and is used for shelter, bedding, containers, storing and cooking food, fire tinder, water craft, fish traps and wrapping corpses. In traditional medicine, an infusion from leaves was drunk, inhaled or used for bathing to treat coughs, colds, congestion, headache, fever and influenza.[13]

Essential oils

Different populations of this species yield different oils but there are two distinct groups. One is rich in terpenic oil but otherwise highly variable with three distinct chemotypes. Another population is rich in methyl cinnamate with two chemotypes.[14]

Horticulture

Melaleuca viridiflora is a useful and adaptable small tree in cultivation, with the red-flowered form being preferred.[15] It is suitable for tropical and subtropical areas where there is high summer rainfall, especially in heavy clay soils.[3] Its open canopy makes it a useful host tree for epiphytes such as Dendrobium.[2]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Brophy, Joseph J.; Craven, Lyndley A.; Doran, John C. (2013). Melaleucas : their botany, essential oils and uses. Canberra: Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research. p. 327. ISBN 9781922137517.

- 1 2 3 Holliday, Ivan (2004). Melaleucas : a field and garden guide (2nd ed.). Frenchs Forest, N.S.W.: Reed New Holland Publishers. pp. 268–269. ISBN 1876334983.

- 1 2 3 4 "Melaleuca viridiflora". Australian Native Plants Society (Australia). Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- 1 2 "Melaleuca viridiflora". Australian Tropical Rainforest Plants. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- ↑ Gaertner, Joseph; Solander, Daniel (1788). De fructibus et seminibus plantarum. London. p. 173. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- ↑ "Melaleuca viridiflora". APNI. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- ↑ Gaertner, Joseph; Solander, Daniel (1788). De fructibus et seminibus plantarum (Figure 35). London. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- ↑ Williams, Cheryll (2010). Medicinal plants in Australia (Volume 2) (1st ed.). Dural, N.S.W.: Rosenberg. p. 285. ISBN 9781877058943. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- ↑ "viridis". Wiktionary. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- ↑ "flos". Wiktionary. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- ↑ "Melaleuca forests and woodlands" (PDF). Wet Tropics Management Authority. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- ↑ Dray Jr., F. Allen.; Bradley C. Bennett; Ted D. Center (2006). "Invasion History of Melaleuca quinquenervia (Cav.) S.T. Blake in Florida". Castanea. 71 (3): 210–225. doi:10.2179/05-27.1.

- ↑ Brock, J., Top End Native Plants, 1988. ISBN 0-7316-0859-3

- ↑ Southwell (ed.), Ian; Lowe (ed.), Robert (1999). Tea tree : the genus melaleuca. Amsterdam: Harwood Academic. pp. 266–270. ISBN 9057024179.

- ↑ Wrigley, John W.; Fagg, Murray (1983). Australian native plants : a manual for their propagation, cultivation and use in landscaping (2nd ed.). Sydney: Collins. p. 352. ISBN 0002165759.