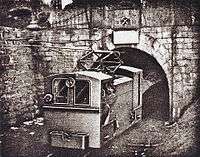

Mine railway

A mine railway (or mine railroad, U.S.), sometimes pit railway, is a railway constructed to carry materials and workers in and out of a mine.[1] Materials transported typically include ore, coal and overburden (also called variously spoils, waste, slack, culm,[2] and tilings; all meaning waste rock). It is little remembered, but the mix of heavy and bulky materials which had to be hauled into and out of mines gave rise to the first several generations of railways, at first made of wood rails, but eventually adding protective iron, steam locomotion by fixed engines and the earliest commercial steam locomotives, all in and around the works around mines.[3]

History

Coal, iron, rail symbiosis

A tendency to concentrate employees started when Benjamin Huntsman, looking for higher quality clock springs, found in 1740[4] that he could produce high quality steel in unprecedented quantities (crucible steel to replace blister steel) in using ceramic crucibles in the same fuel shortage/glass industry inspired reverbatory furnaces that were spurring the coal mining, coking, cast iron cannon foundries, and the much in demand gateway or stimulus products[4] of the glass making industries. These technologies, for several decades, had already begun gradually quickening industrial growth and causing early concentrations of workers so that there were occasional early small factories that came into being.[4]

This trend concentrating effort into bigger central located but larger enterprises[4] turned into a trend spurred by Henry Cort's iron processing patent of 1784[4] leading in short order to foundries collocating near coal mines[3] and accelerating the practice of supplanting the nations cottage industries.[4] With that concentration of employees and separation from dwellings,[3] horsedrawn trams became commonly available as a commuter resource for the daily commute to work.[3] Mine railways were used from 1804 around Coalbrookdale in such industrial concentrations of mines and iron works, all demanding traction-drawing of bulky or heavy loads. These gave rise to extensive early wooden rail ways and initial animal powered trains of vehicles,[4] then successively in just two decades[3] protective iron strips nailed to protect the rails, steam drawn trains (1804) cast iron rails. Later, George Stephenson, inventor of the world-famous Rocket and a board member of a mine, convinced his board to use steam for traction.[5] Next, he petitioned Parliament to license a public passenger railway,[3] founding the Liverpool and Manchester Railway. Soon after the intense public publicity, in part generated by the contest to find the best locomotive won by Stephenson's Rocket, railways underwent explosive growth worldwide, and the industrial revolution gradually went global.[3]

Company towns and child labour

Today, most mine railways are electrically powered; in former times pit ponies, such as Shetland ponies, donkeys, and/or mules were used to haul the early mine trains. In the very cramped conditions of hand-hewn mining tunnels, children were also often used, and the animals were led and tended by boys (called 'mule boys'[6] in the USA, aged 10–12). Until the movement against child labour pushed passage of laws requiring universal mandatory education of children to the sixth grade in the United States, in the Appalachian anthracite coal fields in Eastern Pennsylvania, these urchins were used and known as mule-boys into the 1920s, a position one step up the ladder towards the better pay as an apprentice miner (age 12+) from breaker boys, while the earnings of each stage allowed each group to return considerably more to their hard-scrabble families.

Since many US mines were founded in remote areas and the joint stock companies imported workers from Europe who had to work off their passage in a company town purpose-built to staff the mine – a typical miner's family was constantly in debt to the company for board, rent, groceries, and tools most of their lives, so there was considerable social pressure from family and community for children to earn wages as soon as someone would pay them. Practices in Europe were little different, the mining interests owned the town lands, the buildings, the commercial enterprises established to support the workers from beer gardens, company stores to barbers, dentists, theaters and even doctors offices. The mining companies even ran the real estate offices, and happily sold lands to all comers so individuals gradually invested in such busy communities, including rights of way to railway companies.

Mine haulage

The tram (or dram) cars used for mine haulage are generally called tubs.[7] The term mine car is commonly used in the United States[8]

Rails

There is usually no direct connection from a mine railway to the mine's industrial siding or the public railway network, because of the narrow gauge track that is normally employed. In the United States, the standard gauge for mine haulage is 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm), although gauges from 18 in (457 mm) to 5 ft 6 in (1,676 mm) are used.[9][10]

Original mine railways used wax-impregnated wooden rails attached to wooden sleepers, on which drams were dragged by men, children or animals. This was later replaced by L-shaped iron rails, which were attached to the mine floor, meaning that no sleepers were required and hence leaving easy access for the feet of children or animals to propel more drams.

Wood to cast iron

These early mine railways used wooden rails, which in the early industrial revolution about Coalbrookdale, were soon capped with iron strapping, those were replaced by wrought iron, then with the first steam traction engines, cast iron rails,[5] and eventually steel rails as each was in succession found to last much longer than the previous cheaper rail type.[3] By the time of the first steam locomotive drawn trains, most rails laid were of wrought iron[3] which was outlasting cast iron rails by 8:1. About three decades later, after Andrew Carnegie had made steel competitively cheap, steel rails were supplanting iron for the same longevity reasons.[3]

Motive power

Pit ponies

The Romans were the first to realise the benefits of using animals in their industrial workings, using specially bred pit ponies to power supplementary work such as mine pumps.

Ponies began to be used underground, often replacing child or female labour, as distances from pit head to coal face became greater. The first known recorded use in Britain was in the County Durham coalfield in 1750; however, the use of ponies never made it to the mines of the United States. At the peak in 1913, there were 70,000 ponies underground in Britain. In later years, mechanical haulage was quickly introduced on the main underground roads replacing the pony hauls and ponies tended to be confined to the shorter runs from coal face to main road (known in North East England as "putting") which were more difficult to mechanise. As of 1984, 55 ponies were still at use with the National Coal Board in Britain, chiefly at the modern pit in Ellington, Northumberland.

Dandy wagons were often attached to trains of full drams, to contain a horse or pony. Mining and later railway engineers designed their tramways so that full (heavy) trains would use gravity down the slope, while horses would be used to pull the empty drams back to the workigs. The Dandy wagon allowed for easy transportation of the required horse each time.

Probably the last colliery horse to work underground in a British coal mine, Robbie, was retired from Pant y Gasseg, near Pontypool, in May 1999.[11]

Combustion engines

19th and early 20th century mine railway locomotives were operated with petrol benzene and alcohol / benzene mixtures.[12] Although such engines were probably preferred in metal mines, firedamp safety has been achieved by special types of motors and special exhaust system with cooling water injection, and mesh, chipboard or disc protection over the exhaust openings. These filters contribute greatly to reducing noxious fumes.

For safety (noxious fumes as well as flammability of the fuel) modern mine railway internal combustion locomotives are only operated using diesel fuel. Catalytic scrubbers reduce carbon monoxide. Other locomotives are electric, either battery or trolley.

Battery

Battery powered locomotives and systems solved many of the potential problems that combustion engines present, especially regarding fumes, ventilation and heat generation. However, batteries are heavy items which used to require long periods of charge to produce relatively short periods of full-power operation, resulting in either restricted operations or the need for the doubling-up of equipment purchasing. Hence while popular, battery systems were often practically restricted to mines where systems were short, and moving relatively low-density ore which could explode easily. Today, heavy-duty batteries provide full-shift (8 hours) operations with one or more spare batteries charging. A roller and rack system allows simple and convenient exchange of a depleted battery for a charged one.

Electric

The electric motor technology used pre-1900 to DC with a few hundred volts and a direct supply of power to the motor from the overhead wire enabled the use of efficient, small and sturdy tractors of simple construction. Initially, there was no voltage standard, but by 1914, 250 volts was the standard voltage for underground work in the United States. This relatively low voltage was adopted for safety's sake.[13] This met the needs of mine railways very well, especially for underground working and so the use of electrically powered trains soon became widespread on mine railways.

The first electric mine railway in the world was developed by Siemens & Halske for bituminous coal mining in Saxon Zauckerode near Dresden (now Freital) and was being worked as early as 1882 on the 5th main cross-passage of the Oppel Shaft run by the Royal Saxon Coal Works.

In 1894, the mine railway of the Aachen smelting company, Rothe Erde, was electrically driven, as were subsequently numerous other mine railways in the Rhineland, Saarland Lorraine, Luxembourg and Belgian Wallonia. There were large scale deliveries of electric locomotives for these railways from AEG, Siemens & Halske, Siemens-Schuckert Works (SSW) and the Union Electricitäts-Gesellschaft (UEG) in these countries.

Explosion-proof mining locomotives from Schalker Eisenhütte are used in all the mines owned by Ruhrkohle (today Deutsche Steinkohle).

Compressed air

Compressed-air locomotives were powered by compressed air that were carried on the locomotive in compressed-air containers. This method of propulsion had the advantage of being safe but the disadvantage of high operating costs due to very limited range before it was necessary to recharge the air tanks. Ordinary mine compressed-air systems operating at 100 psi (7 bar) only allowed a few hundred feet of travel. High-pressure systems (up to 2000 psi - 14 bar) were used in large mines, such as Homestake in South Dakota, USA, to increase capacity and range, but required special compressors and distribution piping. Except for very small prospects and remote small mines, battery or diesel locomotives have replaced compressed air.

In operation

Until 1995 the largest single, narrow gauge, above-ground, mine and coal railway network in Europe was in the Leipzig-Altenburg lignite field in Germany. It had 726 kilometres of 900 mm track – the largest 900 mm network in existence. Of this, about 215 kilometres was removable track inside the actual pits and 511 kilometres was fixed track for the transportation of coal to the main rail network.

The last 900 mm gauge mine railway in the German state of Saxony, a major mining area in central Europe, was closed in 1999 at the Zwenkau Mine in Leipzig. Once a very extensive railway network, towards the end it only had 70 kilometres of movable 900 mm track and 90 kilometres of 900 mm fixed railway track within the Zwenkau open cast mine site itself, as well as a 20-kilometre, standard gauge, link railway for the coal trains to the power stations (1995–1999). The closure of this mine marked the end of the history of 900 mm mine railways in the lignite mines of Saxony. In December 1999, the last 900 mm railway in the Central German coal mining field in Lusatia was closed.

Museum and heritage railways

A remnant of the coal railways in the Leipzig-Altenburg Lignite Field may be visited and operated as a museum railway. Regular museum trains also run on the line from Meuselwitz via Haselbach to Regis-Breitingen.

Mine railways in visitor mines

Austria

- Pradeisstollen, Radmer in the Styria

- Schwaz Silver Mine

Germany

- Hesse

- Grube Fortuna, Solms, visitor mine with working shaft, field and pit railway museum with circular track, 600 mm (1 ft 11 5⁄8 in), 2.3 km (1.4 mi) long

- Lower Saxony

- Barsinghausen, Klosterstollen, 600 mm (1 ft 11 5⁄8 in), 13 km (8.1 mi) long

- Clausthal-Zellerfeld-Clausthal, Ottiliae Shaft, open pit railway to the old station in Clausthal, 600 mm (1 ft 11 5⁄8 in), 2.2 km (1.4 mi)

- Goslar, Rammelsberg

- Langelsheim-Lautenthal, Lautenthals Glück Pit

- North Rhine-Westphalia

- Bestwig-Ramsbeck, Ramsbeck Ore Mine

- Kleinenbremen, Kleinenbremen Visitor Mine

- Rhineland-Palatinate

- Steinebach/Sieg, Bindweide Pit

- Saxony

- Annaberg-Buchholz, Markus Röhling Stolln, 600 mm (1 ft 11 5⁄8 in)

- Ehrenfriedersdorf, Sauberg (underground section only), 600 mm (1 ft 11 5⁄8 in)

- Saxony-Anhalt

- Elbingerode (Harz), Drei Kronen & Ehrt visitor mine, 600 mm (1 ft 11 5⁄8 in)

- Sangerhausen-Wettelrode, Röhrigschacht show mine

- Thuringia

- Ilfeld-Netzkater, Rabensteiner Stollen, 600 mm (1 ft 11 5⁄8 in)

- Luxembourg

- Minièresbunn, Fond-de-Gras, 700 mm (2 ft 3 9⁄16 in), 4 km (2.5 mi) long

- National Museum of Luxembourg Iron Ore Mines, circular track

See also

- Industrial railway

- Granite Railway

- Mantrip (shuttle for transporting miners)

- Mine car

- Minecart

- Plateway

- Quarry tub

- Rail profile

- Rail tracks

- Wagonway

References

- ↑ Ellis, Iain (2006). Ellis' British Railway Engineering Encyclopaedia. Lulu.com. ISBN 978-1-8472-8643-7.

- ↑ culture noted and terms listed: culm.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Clark, Ronald W. (1985). 'Works of Man: History of Invention and Engineering, From the Pyramids to the Space Shuttle' (1st American Edition. 8"x10" Hard cover ed.). Viking Penguin, Inc., New York, NY, U.S.A., (1985). pp. 352 (indexed). ISBN 9780670804832.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 James Burke (science historian), Connections (1985), pages: 136-137, pbk: 304 pages, Little Brown & Co., New York, NY, ISBN

- 1 2 George Stephenson#Early locomotives

- ↑ "Jim the Mule Boy (Film Short, title @IMDB)". Edison Film Company. 28 March 1911.

This film is run on a video loop with other historical programing in the Anthracite Coal Mining Museum, Coaldale, Pennsylvania

- ↑ "Mining" (I, Vol II). Wallgate, Wigan, England: Stowager and Sons. 2 December 1893.

|chapter=ignored (help) - ↑ Fay, Albert H. (1920). "Car". A Glossary of the Mining and Mineral Industry. U.S. Department of the Interior. p. 131.

- ↑ Lowrie, Raymond L., ed. (2002). "Excavation, Loading, and Material Transport". SME Mining Reference Handbook. Society for Mining, Metallurgy and Exploration. p. 232. Retrieved 9 October 2012.

- ↑ Stoek, H. H.; Fleming, J. R.; Hoskin, A. J. (July 1922). A Study of Coal Mine Haulage in Illinois. Engineering Experiment Station Bulletin. 132. University of Illinois. pp. 102–103. Retrieved 22 June 2011.

- ↑ Thompson, Ceri (2008). Harnessed: colliery horses in Wales. Cardiff: National Museum Wales. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-7200-0591-2.

- ↑ Heise-Herbst, Bergbaukunde, Springer-Verlag 1910, p. 345 ff.

- ↑ David R. Shearer, Chapger VI: Direct-Current Power Plant Design, Electricity in Coal Mining, McGraw-Hill, New York, 1914.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mining railways. |

- Grubenbahn.de - mine railway site

- Schmalspurige Grubenbahn.de - narrow gauge mine railway site

- Kohlebahn - coal railway site

- Fond-de-Gras industrial and railway park in the Luxembourg mining region

- Mine railway locomotives