Moulinette, Ontario

.jpg)

Moulinette, Ontario is an underwater ghost town in the Canadian province of Ontario. It is one of Ontario's Lost Villages, which were permanently flooded by the creation of the St. Lawrence Seaway in 1958. Families and businesses in Moulinette were moved to the new town of Long Sault before the seaway construction commenced. The village was located as a strip community along Highway 2, on the St. Lawrence River. At the time of the flooding, Moulinette had a population of around 311 residents.[1] The community would have been located in what is now South Stormont township.

Moulinette was settled in the late 1700s by United Empire Loyalists of the King's Royal Regiment from New York. In the nineteenth century many pioneer industries and businesses were established in the village. The origin of the name Moulinette is disputed; it is thought to have originated either from the French term for "little mill" as a reference to the many mills located in the village or from the French word "moulinet", meaning reel or winch as a reference to French ships who navigated the nearby rapids using winches.[2][3]

History

The land which Moulinette occupied was originally given as a land grant to a Sir John Johnson around 1784, however the land ended up in the possession of one of his relatives, Adam Dixson (sometimes recorded as Dixon) who settled the land here.[4] Upon his arrival, Dixson constructed a dam, which ran from the nearby Sheek’s Island to the mainland, in order to generate power; immediately following this, he established a grist mill. The village of Moulinette grew surrounding this mill and dam, and Dixson is credited as its founder.[5]

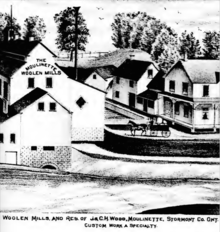

The community had its own post office by the 1830s,[6] and by 1840, the village boasted 100 residents.[7] Two churches had been constructed to serve the community, and many pioneer businesses had been established. During this period, the village had a sawmill, a foundry, a carding machine, a general store and a tavern. Additionally, a brewery operated around this time, however three years after its construction in 1840, it burned and was not rebuilt.[8] The town also had two woollen mills, located on the nearby island.

By the end of the nineteenth century, the construction of the Cornwall Canal allowed Moulinette to prosper as a village. The flooding of the canal had submerged part of the village and the nearby Sheek’s Island; the woollen mills were lost to the flood. During this time, a flour mill and another saw mill were built to replace the lost mills. The village was now home to two hotels, called the Lion and the Pea Green; as well as two general stores, two wharves, a cheese factory, barber shop and an elementary school.[9]

In the beginning of the 1900s, the population had raised to around 311 individuals and the village remained relatively unchanged; many businesses were still established and some businesses had changed to better suit the times such as the blacksmith shop which became a garage.[10] The community relied heavily on tourism with three tourist homes, a motel, and tourists cabins being in operation on top of the two existing hotels.[11]

By 1957, businesses had ceased operations and homes had been relocated to Long Sault in preparations for the floods. The barber shop, called Zina Hill’s Barber Shop, and the Grand Trunk railway station were relocated to the Lost Villages Museum and are now used as exhibit buildings.

St. Lawrence Seaway project and demise

After over half a century of planning, negotiations and development, the St. Lawrence Seaway project became a reality, which called for nine communities along the Canadian side of the St. Lawrence River, including Moulinette, to be permanently relocated then flooded. The intention of the Seaway project was to expand the waterway, allowing ocean-going vessels to travel the St. Lawrence River and replacing the system of locks and canals; this would translate into potentially millions of tonnes of goods being easily transported by ship down the river.[12]

The undertaking was plagued with many delays. From the planning phase, started in 1895, through to commencement of the project in 1954, Canada and the US both disagreed with different parts of the development plans and both World Wars caused further delays. During World War I, both countries' governments were simply too preoccupied to deal with the development plans, and during and immediately after World War II, plans were halted due to a lack of supplies and men. The project became a reality when the Canadian government began the initial phases of planning and construction, essentially forcing the United States to begin to participate. After 59 years, 1954 saw the plans finalized on both sides of the river and Seaway construction could finally commence. Nine communities would be lost.[13][14]

It has been noted that the Commission in Ontario made these plans without consulting those who lived within the village. The government made the decision to move and flood the villages with little thought given to the residents of Moulinette and the surrounding villages and towns. The Canadian government assumed there would be little repercussion, as there were plans in place to relocate all of the residents to newly upgraded towns with newer, improved infrastructure. This was not necessary the case, as many residents could not afford to move to or live in the new towns despite land sales and government aid.[15] Some homes and businesses were moved to the new towns of Ingleside and Long Sault, and some flooded. Additionally, the church and a few other buildings such as the barber shop were moved to become a part of Upper Canada Village and the Lost Villages Museum.

Churches and cemeteries

Moulinette was formerly home to two churches, the Christ Anglican Church and the Moulinette Methodist Church, which later became St. Andrew’s United church. The Moulinette Methodist Church was constructed around 1834 on land donated by the church’s Reverend, Stephen Brownell. In 1871, a wooden steeple was added to the brick church.[16] In 1925, the church joined with the United Church of Canada and was renamed St. Andrews United.[17]

As early as 1830, an Anglican congregation was formed in Moulinette with services being conducted out of private homes or other buildings.[18] In 1836, Adam Dixson donated land to be used as church grounds as well as burial ground, the church, Christ Anglican Church, was constructed shortly after. The church was in use while being built as Dixson's wife died during the construction and her funeral became the first service to be held in the new building.[19] The white, frame, church underwent renovations in 1902 when it was enlarged. In 1925 the church purchased St. George’s Hall from Milles Roches to be used for church activities and in 1931 more land was donated to extend the burial grounds. In preparation for the flooding of the Seaway, a new Christ Church was built in the new town of Ingleside in the 1950s to accommodate the congregation.[20] The church was secularized on June 24, 1957 by Bishop Ernest Reed, and then moved to Upper Canada Village for preservation. The church was restored and sits on site as part of the open air museum.[21][22]

Prior to the flooding of the Seaway, the cemetery accompanying Christ Church was fully transcribed and recorded. The Christ Church Anglican cemetery’s graves were moved in the 1950s and stones encased in the brick wall of the pioneer memorial near Upper Canada Village where they currently remain.[23]

References

- ↑ http://lostvillages.ca/history/the-lost-villages/moulinette/

- ↑ Rutley, R. (1998). Voices from the lost villages. Maxville, Ont.: Casa Maria Publications.

- ↑ http://lostvillages.ca/history/the-lost-villages/moulinette/

- ↑ http://lostvillages.ca/history/the-lost-villages/moulinette/

- ↑ http://lostvillages.ca/history/the-lost-villages/moulinette/

- ↑ http://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/discover/postal-heritage-philately/post-offices-postmasters/Pages/item.aspx?IdNumber=3242&

- ↑ http://www.ghosttownpix.com/lostvillages/moulinet.html

- ↑ http://lostvillages.ca/history/the-lost-villages/moulinette/

- ↑ http://www.ghosttownpix.com/lostvillages/moulinet.html

- ↑ http://www.ghosttownpix.com/lostvillages/moulinet.html

- ↑ http://www.ghosttownpix.com/lostvillages/moulinet.html

- ↑ Camu, P. "The St. Lawrence Seaway." The Town Planning Review. 28. no. 2 (1957): 89-110

- ↑ http://www.greatlakes-seaway.com/en/seaway/history/

- ↑ Macfarlane, D. (n.d.). Negotiating a river: Canada, the US, and the creation of the St. Lawrence Seaway.

- ↑ Macfarlane, D. (n.d.). Negotiating a river: Canada, the US, and the creation of the St. Lawrence Seaway.

- ↑ http://lostvillages.ca/history/the-lost-villages/moulinette/

- ↑ Rutley, R. (1998). Voices from the lost villages. Maxville, Ont.: Casa Maria Publications.

- ↑ http://www.archeion.ca/christ-church-moulinette-ont

- ↑ Rutley, R. (1998). Voices from the lost villages. Maxville, Ont.: Casa Maria Publications.

- ↑ http://lostvillages.ca/history/the-lost-villages/moulinette/

- ↑ http://lostvillages.ca/history/the-lost-villages/moulinette/

- ↑ http://www.archeion.ca/christ-church-moulinette-ont

- ↑ Rutley, R. (1998). Voices from the lost villages. Maxville, Ont.: Casa Maria Publications.

External links

Coordinates: 45°01′40″N 74°51′21″W / 45.0278°N 74.8559°W