Musculoskeletal disorder

| Musculoskeletal disorders | |

|---|---|

| |

| Carpal tunnel syndrome is a common musculoskeletal disorder, and is often treated with a splint. | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| MeSH | D009140 |

Musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) are injuries or pain in the body's joints, ligaments, muscles, nerves, tendons, and structures that support limbs, neck and back.[1] MSDs can arise from a sudden exertion (e.g., lifting a heavy object), or they can arise from making the same motions repeatedly repetitive strain, or from repeated exposure to force, vibration, or awkward posture.[2] Injuries and pain in the musculoskeletal system caused by acute traumatic events like a car accident or fall are not considered musculoskeletal disorders.[3] MSDs can affect many different parts of the body including upper and lower back, neck, shoulders and extremities (arms, legs, feet, and hands).[4] Examples of MSDs include carpal tunnel syndrome, epicondylitis, tendinitis, back pain, tension neck syndrome, and hand-arm vibration syndrome.[2]

Causes

MSDs can arise from the interaction of physical factors with ergonomic, psychological, social, and occupational factors.[5]

Biomechanical

MSDs are caused by biomechanical load which is the force that must be applied to do tasks, the duration of the force applied, and the frequency with which tasks are performed.[6] Activities involving heavy loads can result in acute injury, but most occupation-related MSDs are from motions that are repetitive, or from maintaining a static position.[7] Even activities that do not require a lot of force can result in muscle damage if the activity is repeated often enough at short intervals.[7] MSD risk factors involve doing tasks with heavy force, repetition, or maintaining a nonneutral posture.[7] Of particular concern is the combination of heavy load with repetition.[7] Although awkward posture is often blamed for lower back pain, a systematic review of the literature failed to find a consistent connection.[8]

Individual differences

People vary in their tendency to get MSDs. Gender is a factor with a higher rate in women than men.[7] Obesity is also a factor, with overweight individuals having a higher risk of some MSDs, specifically lower back.[9]

Psychosocial

There is a growing consensus that psychosocial factors are another cause of some MSDs.[10] Some theories for this causal relationship found by many researchers include increased muscle tension, increased blood and fluid pressure, reduction of growth functions, pain sensitivity reduction, pupil dilation, body remaining at heightened state of sensitivity. Although research findings are inconsistent at this stage,[11] some of the workplace stressors found to be associated with MSDs in the workplace include high job demands, low social support, and overall job strain.[10][12][13] Researchers have consistently identified causal relationships between job dissatisfaction and MSDs. For example, improving job satisfaction can reduce 17-69 per cent of work-related back disorders and improving job control can reduce 37-84 per cent of work-related wrist disorders.[14]

Occupational

Because workers maintain the same posture over long work days and often several years, even natural postures like standing can lead to MSDs like low back pain, but postures which are less natural like twisting or tension in the upper body are typically contributors to the development of MSDs because of the unnatural biomechanical load of these postures.[2][15] There is evidence that posture contributes to MSDs of the neck, shoulder, and back.[2] Repeated motion is another risk factor for MSDs of occupational origin because workers can perform the same movements repeatedly over long periods of time (e.g. typing leading to carpal tunnel syndrome), which can wear on the joints and muscles involved in the motion in question.[2] Workers doing repetitive motions at a high pace of work with little recovery time and workers with little to no control over the timing of motions (e.g. workers on assembly lines) are also prone to MSDs due to the motion of their work.[15] Force needed to perform actions on the job can also be associated with higher MSD risk in workers, because movements which require more force can fatigue muscles quicker which can lead to injury and/or pain.[2] Additionally, exposure to vibration (as in truck drivers or construction workers, for example) and extreme hot or cold temperatures can affect a worker's ability to judge force and strength, which can lead to development of MSDs.[15] Vibration exposure is also associated with hand-arm vibration syndrome, which has symptoms of lack of blood circulation to the fingers, nerve compression, tingling, and/or numbness.[16]

Diagnosis

Assessment of MSDs are based on self-reports of symptoms and pain as well as physical examination by a doctor.[2] Doctors rely on medical history, recreational and occupational hazards, intensity of pain, a physical exam to locate the source of the pain, and sometimes lab tests, x-rays, or an MRI[17] Doctors look for specific criteria to diagnose each different musculoskeletal disorder, based on location, type, and intensity of pain, as well as what kind of restricted or painful movement a patient is experiencing.[2] A popular measure of MSDs is the Nordic Questionnaire that has a picture of the body with various areas labeled and asks the individual to indicate in which areas they have experienced pain, and in which areas has the pain interfered with normal activity.[4]

Prevention

Prevention of MSDs relies upon identification of risk factors, either by self-report, observation on the job, or measurement of posture which could lead to MSDs.[18] Once risk factors have been determined, there are several intervention methods which could be used to prevent the development of MSDs. The target of MSD prevention efforts is often the workplace in order to identify incidence rates of both disorders and exposure to unsafe conditions.[19]

Workplace controls

Groups who are at particular risk can be identified, and modifications to the physical and psychosocial environment can be made.[19] Approaches to prevention in workplace settings include matching the person's physical abilities to the tasks, increasing the person's capabilities, changing how tasks are performed, or changing the tasks.[20] Employers can also utilize engineering and administrative controls to prevent injury happening on the job.[3] Implementation of engineering controls is the process of designing or redesigning the workplace to account for strengths, weaknesses, and needs of the working population- examples would be workstation layout changes to be more efficient or reducing bending over, or moving necessary tools within shorter reach of the worker's station.[3] Employers may also utilize administrative controls like reducing number of hours in a certain position, limiting overtime, or including more breaks during shifts in order to reduce amount of time at risk for each worker.[3]

Ergonomics

Encouraging the use of proper ergonomics not only includes matching the physical ability of the worker with the correct job, but it deals with designing equipment that is correct for the task.[21] Limiting heavy lifting, training, and reporting early signs of injury are examples that can prevent MSD.[22] Employers can provide support for employees in order to prevent MSD in the workplace by involving the employees in planning, assessing, and developing standards of procedures that will support proper ergonomics and prevent injury.[22]

One focus of ergonomic principles is maintaining neutral postures, which are postures in which muscles are at their normal length and able to generate the most force, while reducing stress and possible injury to muscles, tendons, nerves, and bones- therefore, in the workplace or in everyday life, it is ideal for muscles and joints to maintain neutral positions.[23] Additionally, to prevent hand, wrist, and finger injuries, understanding when to use pinch grips (best for fine motor control and precise movements with low force) and power grips (best for high-force movements done repeatedly) is important for employees and general tasks outside the workplace.[23] The choice of tools should match that of the proper grip and be conducive to neutral postures, which is important for employers to consider when purchasing equipment.[23] In order to reduce injuries to the low back and spine, it is recommended to reduce weight and frequency of lifting cycles as well as decreasing the distance between the body and the load to reduce the torque force on the back for workers and individuals doing repeated lifting to avoid fatigue failure of the spine.[23] The shape of objects being lifted should also be considered, especially by employers, because objects which are easier to grip, lift, and access present less stress on the spine and back muscles than objects which are awkwardly shaped and difficult to access.[23]

The National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) has published ergonomic recommendations for several industries, including construction, mining, agriculture, healthcare, and retail, among others.[24]

Epidemiology

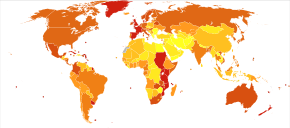

General population

MSDs are an increasing healthcare issue globally, being the second leading cause of disability.[7] For example, in the U.S. there were more than 16 million strains and sprains treated in 2004, and the total cost for treating MSDs is estimated to be more than $125 billion per year.[25] In 2006 approximately 14.3% of the Canadian population was living with a disability, with nearly half due to MSDs.[26] Neck pain is one of the most common complaints, with about one fifth of adults worldwide reporting pain annually.[27]

Workplace

Most workplace MSD episodes involve multiple parts of the body.[28] MSDs are the most frequent health complaint by European, United States and Asian Pacific workers.[29] and the third leading reason for disability and early retirement in the U.S.[12] The incidence rate for MSDs among the working population in 2014 was 31.9 newly diagnosed MSDs per 10,000 full-time workers.[30] In 2014, the median days away from work due to MSDs was 13, and there were 10.4 cases per 10,000 full-time workers in which an MSD caused a worker to be away from work for 31 or more days.[30] MSDs are widespread in many occupations, including those with heavy biomechanical load like construction and factory work, and those with lighter loads like office work.[12] The transportation and warehousing industries have the highest incidence rate of musculoskeletal disorders, with an incidence rate of 89.9 cases per 10,000 full-time workers.[30] Healthcare, manufacturing, agriculture, wholesale trade, retail, and recreation industries all have incidence rates above 35 per 10,000 full-time workers.[30] For example, a national survey of U.S. nurses found that 38% reported an MSD in the prior year, mainly lower back injury.[31] The neck and back are the most common sites of MSDs in workers, followed by the upper limbs and lower limbs.[30] The Bureau of Labor Statistics reports that 31.8 new cases of MSDs per 10,000 full-time workers per year are due to overexertion, bodily reaction, or repetitive motions.[30]

See also

References

- ↑ "CDC - NIOSH Program Portfolio : Musculoskeletal Disorders : Program Description". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2016-03-24.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "CDC - NIOSH Publications and Products - Musculoskeletal Disorders and Workplace Factors (97-141)". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2016-03-24.

- 1 2 3 4 Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and. "CDC - Workplace Health - Implementation - Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders (WMSD) Prevention". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2016-03-24.

- 1 2 Kuorinka, I.; Jonsson, B.; Kilbom, A.; Vinterberg, H.; Biering-Sørensen, F.; Andersson, G.; Jørgensen, K. (1987). "Standardised Nordic questionnaires for the analysis of musculoskeletal symptoms". Applied Ergonomics. 18 (3): 233–7. doi:10.1016/0003-6870(87)90010-x. PMID 15676628.

- ↑ Gatchel, R. J., & Kishino, N. (2011). Pain, musculoskeletal injuries, and return to work. In J. C. Quick & L. E. Tetrick (Eds.), Handbook of occupational health psychology (2nd ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- ↑ Barriera-Viruet H.; Sobeih T. M.; Daraiseh N.; Salem S. (2006). "Questionnaires vs observational and direct measurements: A systematic review". Theoretical Issues in Ergonomics Science. 7 (3): 261–284. doi:10.1080/14639220500090661.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Barbe, Mary F; Gallagher, Sean; Massicotte, Vicky S; Tytell, Michael; Popoff, Steven N; Barr-Gillespie, Ann E (2013). "The interaction of force and repetition on musculoskeletal and neural tissue responses and sensorimotor behavior in a rat model of work-related musculoskeletal disorders". BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 14: 303. doi:10.1186/1471-2474-14-303. PMC 3924406

. PMID 24156755.

. PMID 24156755. - ↑ Roffey D. M., Wai E. K., Bishop P., Kwon B. K., Dagenais S. (2010). "Causal assessment of awkward occupational postures and low back pain: results of a systematic review". Spine Journal: Official Journal of the North American Spine Society. 10 (1): 89–99. doi:10.1016/j.spinee.2009.09.003.

- ↑ Kerr M. S.; Frank J. W.; Shannon H. S.; Norman R. W.; Wells R. P.; Neumann P.; Bombardier C. (2001). "Biomechanical and psychosocial risk factors for low back pain at work". American Journal of Public Health. 91 (7): 1069–1075. doi:10.2105/AJPH.91.7.1069.

- 1 2 Safety, Government of Canada, Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and. "Musculoskeletal Disorders - Psychosocial Factors : OSH Answers". www.ccohs.ca. Retrieved 2016-04-07.

- ↑ Courvoisier D. S.; Genevay S.; Cedraschi C.; Bessire N.; Griesser-Delacretaz A.-C.; Monnin D.; Perneger T. V. (2011). "Job strain, work characteristics and back pain: A study in a university hospital". European Journal of Pain. 15 (6): 634–640. doi:10.1016/j.ejpain.2010.11.012.

- 1 2 3 Sprigg C. A.; Stride C. B.; Wall T. D.; Holman D. J.; Smith P. R. (2007). "Work characteristics, musculoskeletal disorders, and the mediating role of psychological strain: A study of call center employees". Journal of Applied Psychology. 92 (5): 1456–1466. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.92.5.1456.

- ↑ Hauke A.; Flintrop J.; Brun E.; Rugulies R. (2011). "The impact of work-related psychosocial stressors on the onset of musculoskeletal disorders in specific body regions: A review and meta-analysis of 54 longitudinal studies". Work & Stress. 25 (3): 243–256. doi:10.1080/02678373.2011.614069.

- ↑ Punnett (2004). "Work-related Musculoskeletal Disorders: The Epidemiologic Evidence and the Debate". Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology. 14: 13–23. doi:10.1016/j.jelekin.2003.09.015.

- 1 2 3 Safety, Government of Canada, Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and. "Work-related Musculoskeletal Disorders (WMSDs) - Risk Factors : OSH Answers". www.ccohs.ca. Retrieved 2016-03-25.

- ↑ "CDC - NIOSH Publications and Products - Criteria for a Recommended Standard: Occupational Exposure to Hand-Arm Vibration (89-106)". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2016-03-25.

- ↑ "Musculoskeletal Pain: Tendonitis, Myalgia & More | Cleveland Clinic". my.clevelandclinic.org. Retrieved 2016-03-24.

- ↑ NIOSH [2014]. Observation-based posture assessment: review of current practice and recommendations for improvement. By Lowe BD, Weir PL, Andrews DM. Cincinnati, OH: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 2014–131.

- 1 2 Côté, Julie N.; Ngomo, Suzy; Stock, Susan; Messing, Karen; Vézina, Nicole; Antle, David; Delisle, Alain; Bellemare, Marie; Laberge, Marie; St-Vincent, Marie (2013). "Quebec Research on Work-related Musculoskeletal Disorders". Relations industrielles. 68 (4): 643. doi:10.7202/1023009ar.

- ↑ Rostykus W.; Ip W.; Mallon J. (2013). "Musculoskeletal disorders". Professional Safety. 58 (12): 35–42.

- ↑ "Hospital eTool: Healthcare Wide Hazards - Ergonomics". www.osha.gov. Retrieved 2016-04-07.

- 1 2 "Safety and Health Topics | Ergonomics". www.osha.gov. Retrieved 2016-04-07.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Moore, S.M., Torma-Krajewski, J., & Steiner, L.J. (2011). Practical Demonstrations of Ergonomic Principles. Report of Investigations 9684. NIOSH. Retrieved 24 March 2016.

- ↑ "CDC - Ergonomics and Musculoskeletal Disorders - NIOSH Workplace Safety and Health Topic". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2016-03-25.

- ↑ Gallagher, Sean; Heberger, John R. (2013-02-01). "Examining the Interaction of Force and Repetition on Musculoskeletal Disorder Risk A Systematic Literature Review". Human Factors: the Journal of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society. 55 (1): 108–124. doi:10.1177/0018720812449648. ISSN 0018-7208. PMID 23516797. Retrieved 2015-04-14.

- ↑ Goodridge, Donna; Lawson, Josh; Marciniuk, Darcy; Rennie, Donna (2011-09-20). "A population-based profile of adult Canadians living with participation and activity limitations". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 183 (13): E1017–E1024. doi:10.1503/cmaj.110153. ISSN 0820-3946. PMID 21825051. Retrieved 2015-04-14.

- ↑ McLean, Sionnadh Mairi; May, Stephen; Klaber-Moffett, Jennifer; Sharp, Donald Macfie; Gardiner, Eric (07/01/2010). "Risk factors for the onset of non-specific neck pain: a systematic review". Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 64 (7): 565–572. doi:10.1136/jech.2009.090720. ISSN 1470-2738. PMID 20466711. Retrieved 2015-04-14. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Haukkal, Eija; Leino-Arjasl, Päivi; Ojajärvil, Anneli; Takalal, Esa-Pekka; Viikari-Juntural, Eira; Riihimäkil, Hilkka (2011). "Mental stress and psychosocial factors at work in relation to multiple-site musculoskeletal pain: A longitudinal study of kitchen workers". European Journal of Pain. 15 (4): 432–8. doi:10.1016/j.ejpain.2010.09.005. PMID 20932789.

- ↑ Hauke, Angelika; Flintrop, Julia; Brun, Emmanuelle; Rugulies, Reiner (July 1, 2011). "The impact of work-related psychosocial stressors on the onset of musculoskeletal disorders in specific body regions: A review and meta-analysis of 54 longitudinal studies". Work & Stress. 25 (3): 243–256. doi:10.1080/02678373.2011.614069. ISSN 0267-8373. Retrieved 2015-04-14.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Occupational Injuries/Illnesses and Fatal Injuries Profiles". Bureau of Labor Statistics. United States Department of Labor. 2014. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ↑ American Nurses Association. (2001). Nursingworld organizational health & safety survey. Silver Spring, MD.

External links

- Musculoskeletal disorders Single Entry Point European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (OSHA)

- Good Practices to prevent Musculoskeletal disorders European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (OSHA)

- Musculoskeletal disorders homepage Health and Safety Executive (HSE)

- Hazards and risks associated with manual handling of loads in the workplace European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (OSHA)