Narce

Narce was a Faliscan settlement in Italy located 5 kilometers south of Falerii (modern Civita Castellana). Its residents spoke an Italic language related to Latin.[1] It was inhabited from the 2nd millennium to the 3rd century B.C. The ancient name of the settlement is uncertain, but it may have been called Fescennium.[2]

The material culture, religion, and history of the Faliscans shares much in common with that of the Etruscans. Narce interacted with Etruscan settlements in all periods of its inhabitation, maintaining especially close relations with the nearby Etruscan city of Veii.[3] Ultimately both groups of people met the same fate under Roman conquest.

Narce was at the center of an impressive network of roads, which gave it access to Veii, Nepi, Falerii Veteres, Capena, and other neighboring settlements.[4] It likely owed its prosperity to its position as a trading post and waystation.[5]

Topography and Inhabitation

Narce comprises a nucleated settlement of three hills in the Treia River Vally between Mazzano Romano and Calcata.[6] It takes its name from the northernmost hill, which was the first to be occupied.[7] The others that formed the settlement are Monte li Santi and Pizzo Piede.[8]

The inhabitants of Bronze Age Narce lived along the Treia River in low areas below the city's cliffs.[9] Archaeological evidence suggests they burned the vegetation in the area before building huts and possibly a palisade to enclose the city.[10] From the 14th century through the Protovillanovan period (12th-11th century) the people living there planted grains and raised pigs and sheep for meat, milk, and wool. During this period Narce may have served as a focus for smaller sites in its surrounding hinterland.[11] Metalwork and glass beads among archaeological finds indicate that even at this period Narce was involved in long-range trade routes.[12]

During the Villanovan Iron Age (900-700 B.C.), settlements grew up in higher areas to the north and south.[13] The latest habitation on the lower-lying part of the site dates to the 7th century B.C.[14] This low area was used exclusively for burials from the second half of that century onward.[15] At this time the center of the settlement was at Monte li Santi.

The site was reoccupied during the 4th and 3rd centuries B.C., when its central point was on Pizzo Piede (although the other hills were also occupied).[16][17] When the Romans annexed the region in 241 B.C., the population of Narce dispersed.[18] The site was reoccupied yet again during the 1st-3rd centuries A.D.[19]

Excavations

The site was discovered in the late 19th century, with the first recorded excavations taking place in 1889 and being published in 1894.[20] These excavations uncovered 21 cemeteries, most on the ridges to the east, south, and west.[21] Further excavations were undertaken by Frothingham (1896), Paille and Mengarelli (1897), del Drago (published 1902), and Mancinelli-Scott (1897).

The tombs of Narce produced the site's most significant archaeological finds. The discoveries made therein were the basis of the collection of the National Etruscan Museum, now housed in the Villa Giulia in Rome.[22] Excavated Italic material was also dispersed to several American museums, with Arthur Frothingham acting as agent to select and send back the artifacts. Tomb finds also went to Florence, Paris, Copenhagen, and Berlin.[23] The University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology received the largest and most representative sampling of grave goods.[24]

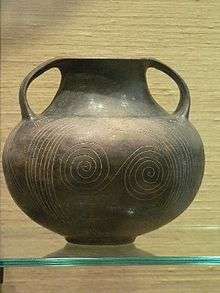

The cemeteries date from the 8th-6th centuries B.C. (the Villanovan and Orientalizing periods), representing perhaps four or five generations at the settlement.[25] The earliest tombs were well-tombs, dug pits with an urn at the bottom containing the cremated remains of the deceased.[26] Trench tombs later became more popular, following the growth of the trend toward inhumation.[27] It was typical for a small selection of goods to be buried with the cremated remains of the deceased.

The finds from Narce are significant because their original context was documented and their groupings in individual tombs was preserved. With this context, grave goods can be used to determine the sex and social status or occupation of the deceased,[28] and can in turn provide information about life in that society.

Ornamental cups, spits for roasting meat, bronze belts, armor, swords, spears, razors, and feasting equipment were found in a men's burials at Narce. Women's burials include cups, plates, and bowls as well as fibulae (brooches), jewelry, and spinning equipment.[29] War chariots or symbolic parts of a chariot were also found, sometimes with sacrificed horses.[30] Burials from Narce contain a token item from the opposite gender of the deceased. For example, Tomb 43, which held the remains of the so-called "Narce warrior," also contained two spindle whorls and four women's brooches.[31] This may indicate that a ritual took place at the funeral where a family member of the opposite sex offered a token gift to the deceased.[32]

There is also evidence for children's burials at Narce. A stone sarcophagus found in Tomb 102F could not hold a child larger than a toddler, and was determined to have held the body of a small girl.[33] The child was buried with jewelry and miniature versions of vases and bowls, child-sized variants on the standard adult grave goods.

As a whole the quantity and quality of the grave goods indicate that the inhabitants of Narce over these four or five generations were quite well-to-do.

Notes

- ↑ Turfa 2005, p.13

- ↑ Potter 1974, p. 33

- ↑ Turfa 2005, p. 4

- ↑ Potter 1974, p. 20

- ↑ Potter 1974, p. 21

- ↑ Potter 1974, p. 7

- ↑ Potter 1974, p. 21

- ↑ Potter 1974, p. 11-13

- ↑ Turfa 2005, p. 14

- ↑ Turfa 2005, p. 14

- ↑ Barker and Rasmussen 1998, p. 56

- ↑ Turfa 2005, p. 14

- ↑ Barker and Rasmussen 1998, p. 63

- ↑ Turfa 2005, p. 14

- ↑ Turfa 2005, p. 14

- ↑ Turfa 2005, p. 14

- ↑ Potter 1974, p. 22

- ↑ Potter 1974, 321

- ↑ Turfa 2005, p. 14

- ↑ Potter 1976, p. 9

- ↑ Potter 1976, p. 9

- ↑ Turfa 2005, p.6

- ↑ Turfa 2005, p. 14

- ↑ Davison 1972,p. 4

- ↑ Turfa 2005, p. 14

- ↑ Turfa 2005, 15

- ↑ Turfa 2005, 15

- ↑ Turfa 2005, p. 7

- ↑ Turfa 2005, p. 15

- ↑ Turfa 2005, 15

- ↑ Turfa 2005, 16

- ↑ Turfa 2005

- ↑ Turfa 2005, p. 20

References

- Barker, Graeme and Tom Rasmussen. The Etruscans. Blackwell Publishers, 1998.

- Davison, Jean M. Seven Italic Tomb-Groups from Narce.Leo S. Olschki, 1972.

- Potter, T.W. Faliscan Town in Southern Etruria. British School at Rome, 1976.

- Turfa, Jean Macintosh. Catalogue of the Etruscan Gallery of the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. University of Pennsylvania, 2005.

External links

Coordinates: 42°17′21″N 12°24′51″E / 42.2892°N 12.4142°E