Nares-jux

The nares-jux (нарс-юх) or Siberian lyre[1] is a musical instrument, a type of box-lyre, played by Uralic peoples of the Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug of Russian Siberia.

Etymology

The Ostyak (Khanty people) term the instrument nares-jux, meaning "musical wood"[2] or "singing tree"[3] in the Khanty language. The same instrument is played by the Mansi people (formerly known as Vogul), and is known as sangkultap (or sangvyltap, санквылтап) in the Vogul language.[2]

Various names and spellings include: naresyuk, nars-yukh,[4] naras-yux, nars-juh, nares-yuk, possibly nanus[5] narsus,[6] panan-juh, or shongoort.[7]

Construction and playing

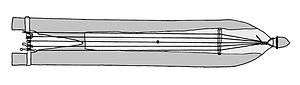

In the traditional form, the hollow body of the instrument is carved from a single piece of wood (fir or cedar) around 100 cm long. One end is pointed and the other is forked into two arms which carry a crossbar to hold the tuning mechanism. The soundboard is around 0.5 cm in thickness and covers the whole of the body except the forked end. A bridge is fitted, towards the pointed end of the body. A soundpost is fitted inside the instrument, between the back of the body and the soundboard, to provide support at the position of the bridge. There are typically five strings of tendon or gut. Wood or bone tuning levers are used to tension the strings by pulling them around the crossbar.[8][9][6] The strings are tuned diatonically, to a major or minor pentachord.[1][8] These lyres are also distinguished by the placing of pebbles within the resonating body, causing a rattle.[10] Modern examples may have metal strings, an increased number of strings, tuning pegs or pins, and a body which lacks the forked end.

The nares-jux is played with a blocking technique: the player strums the strings with the right hand and uses the fingers of the left hand to damp those strings which are not intended to sound.[8]

See also

- Khutang, an arched-angular lap-harp of the Khanty and Mansi

- Tonkori, a similarly-shaped long five-string zither of the Ainu people of northern Japan

References

- 1 2 Curt Sachs (22 September 2006). The History of Musical Instruments. Courier Dover Publications. pp. 267–. ISBN 978-0-486-45265-4. Retrieved 20 May 2012.

- 1 2 Sibyl Marcuse (April 1975). A survey of musical instruments. Harper & Row. p. 376. ISBN 978-0-06-012776-3. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- ↑ Sovetskiĭ komitet solidarnosti stran Azii i Afriki; Institut vostokovedenii︠a︡ (Akademii︠a︡ nauk SSSR); Institut Afriki (Akademii︠a︡ nauk SSSR) (1984). Asia and Africa today. Asia and Africa Today. p. 27. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- ↑ Frederick Crane (1972). Extant medieval musical instruments: a provisional catalogue by types. University of Iowa Press. p. 8. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- ↑ Lola Romanucci-Ross; Daniel E. Moerman (1991). The Anthropology of medicine: from culture to method. Bergin & Garvey. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-89789-262-9. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- 1 2 Marjorie Mandelstam Balzer (1 November 1999). The Tenacity of Ethnicity: A Siberian Saga in Global Perspective. Princeton University Press. pp. 192–. ISBN 978-0-691-00673-4. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- ↑ Americus Featherman (1891). Social history of the races of mankind. Ticknor. pp. 551–. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- 1 2 3 Heikki Silvet (1991). Hanti Melodies Played on the Lyre. Estonian Academy of Sciences. pp. 17–20.

- ↑ Otto Andersson (1930). The Bowed Harp. Reeves, London. pp. 136–8.

- ↑ Encyclopaedia Britanica, Inc; William Benton (1974). The New Encyclopaedia Britannica. Encyclopaedia Britannica. p. 419. ISBN 978-0-85229-290-7. Retrieved 18 May 2012.