Nasal glial heterotopia

"Nasal glial heterotopia" refers to congenital malformations of displaced normal, mature glial tissue, which are no longer in continuity with an intracranial component. This is distinctly different from an encephalocele, which is a herniation of brain tissue and/or leptomeninges, that develops through a defect in the skull, where there is a continuity with the cranial cavity.[1]

Classification

While nasal glial heterotopia (NGH) is the preferred term, synonyms have included nasal glioma. However, this term is to be discouraged, as it implies a neoplasm or tumor, which it is not. By definition, nasal glial heterotopia is a specific type of choristoma. It is not a teratoma, however, which is a neoplasm comprising all three germ cell layers (ectoderm, endoderm, mesoderm). As a congenital malformation or ectopia, it is distinctly different from the trauma or iatrogenic development of an encephalocele.[1]

Signs and symptoms

Patients come to clinical attention early in life (usually at birth or within the first few months), with a firm subcutaneous nodule at bridge of nose, or as a polypoid mass within the nasal cavity, or somewhere along the upper border of the nasal bow. If the patient presents with an intranasal mass, there may be obstruction, chronic rhinosinusitis, or nasal drainage. If there is a concurrent cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak, then an encephalocele is much more likely.[1]

This lesion is separated into two types based on the anatomic site of presentation:

- Extranasal (60%): Subcutaneous bridge of nose

- Intranasal (30%): Superior nasal cavity

- Mixed (10%): Subcutaneous tissues and nasal cavity (larger lesions)

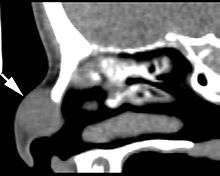

Imaging findings

Imaging studies are performed before surgery or biopsy to preclude an intracranial connection. Images usually show a sharply circumscribed but expansile mass. It may be difficult to exclude the intracranial connection if the defect is small whether employing computed tomography or magnetic resonnance.[1]

Pathology findings

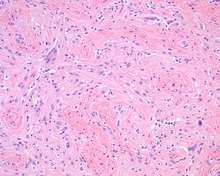

The cut surface shows a smooth, homogeneous glistening to slippery cut surface, showing an appearance similar to brain. Sometimes, it is quite firm, especially when there is a large amount of associated fibrosis. The lesions are usually <2 cm in greatest dimension.[1][2]

The overlying skin or squamous mucosa is intact and uninvolved by the process. There is normal glial tissue set within a fibrous connective tissue stroma. There is such blending, that the underlying process may be difficult to detect without special studies. In a few cases, large gemistocytes, neurons, choroid plexus, ependyma, and retinal pigmented cells may be seen.[1][2]

Histochemistry

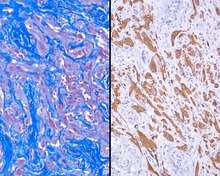

A trichrome stain will highlight the dual components well, with the glial tissue staining red, while the background fibrosis stains a bright blue.[1]

Immunohistochemistry

The glial tissue is highlighted with S100 protein and with glial fibrillary acidic protein, although the latter is much more sensitive for glial tissue.[1]

Differential diagnoses

The most common missed lesion is within the nasal cavity, where a fibrosed nasal polyp may be considered. However, it does not have glial tissue. Further, a polyp usually has mucoserous glands. The lesion is frequently misintrepreted as scar in the subcutaneous tissues, but scar in a <2 year old child would be uncommon. Special stains are frequently required to highlight the diagnosis.[1]

Management

Although surgery is the treatment of choice, it must be preceded by imaging studies to exclude an intracranial connection. Potential complications include meningitis and a cerebrospinal fluid leak. Recurrences or more correctly persistence may be seen in up to 30% of patients if not completely excised.[1]

Epidemiology

Nasal glial heterotopia is rare, while an encephalocele is uncommon. NGH usually presents in infancy, while encephalocele may present in older children and adults. It is seen in both genders equally.[1]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Penner, C. R.; Thompson, L. (2003). "Nasal glial heterotopia: A clinicopathologic and immunophenotypic analysis of 10 cases with a review of the literature". Annals of diagnostic pathology. 7 (6): 354–359. PMID 15018118.

- 1 2 Kardon, D. E. (2000). "Nasal glial heterotopia". Archives of pathology & laboratory medicine. 124 (12): 1849–1842. doi:10.1043/0003-9985(2000)124<1849:NGH>2.0.CO;2. PMID 11100076.

Further reading

Lester D. R. Thompson; Bruce M Wenig (2011). Diagnostic Pathology: Head and Neck: Published by Amirsys. Hagerstown, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 1:1–2. ISBN 1-931884-61-7.