Neferirkare Kakai

| Neferirkare Kakai | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

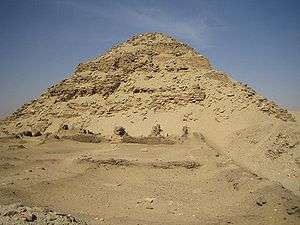

Pyramid of Neferirkare at Abusir | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pharaoh | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reign | 2475–2455 BC[1] (5th Dynasty) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Sahure | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Successor |

Neferefre/ Shepseskare? | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Consort | Khentkaus II | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Father | Sahure or Userkaf | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mother | Neferetnebty or Khentkaus I | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 2455 BC | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monuments | Pyramid at Abusir | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Neferirkare Kakai was an Ancient Egyptian pharaoh, the third king of the Fifth Dynasty. He succeeded his father Sahure on the throne and was in turn succeeded by his son Neferefre. His praenomen, Neferirkare, means "Beautiful is the Soul of Ra".[2] His Horus name was Userkhau,[3] his Golden Horus name Sekhemunebu and his Nebti name Khaiemnebty.

Family

It was not known who Neferirkare's parents were in the past. Some Egyptologists viewed him as a son of Userkaf and Khentkaus I.[4] This is now known to be incorrect: reliefs from Sahure's causeway show that his father was Sahure and his mother was probably Queen Meretnebty[5]

Scenes discovered in Sahure's funerary temple, the causeway region, indicate, however, that Neferirkare may have been the son of Sahure and Queen Meretnebty. K. Sethe thought from broken records that the queen's name was Neferhanebty. This information is now known (see El Awady references above) to be incorrect. [6] One theory holds that Neferirkare may have been known as Prince Ranefer when he was young, and had a (twin?) brother named Netjerirenre, who may have taken the throne under the name of Shepseskare.[6]

Neferirkare married Queen Khentkaus II and had 2 sons who both became pharaoh: Ranefer—under the name Neferefre—and Niuserre.[4]

Reign

Little is known about his reign. Manetho's Epitome assigns Neferirkare a reign of 20 years but verso 5 of the damaged Palermo Stone preserves the year of his 5th cattle count (Year 9 on a biennial count).[7] His following years were lost in the missing portion of the document. The Czech Egyptologist Miroslav Verner maintains, however, that it cannot have been as long as 20 years due to the unfinished state of Neferirkare's Abusir pyramid complex.

Since the annals in the Palermo stone terminate around Neferirkare’s rule, some scholars have suggested that they might have been compiled during his reign. However, evidence from the other side of the stela implies that the document covered the reigns of later Old Kingdom kings. Hence, it is possible that these Annals were composed during the time of Nyuserre Ini who had a long reign and was the third successor to Neferirkare, after the ephemeral Shepseskare and the short-lived Neferefre.

A decree, exempting personnel belonging to a temple from undertaking compulsory labour, shows that taxation was imposed on everybody as a general rule. An important cache of Old Kingdom administrative papyri, the Abusir Papyri, was discovered in Neferirkare's mortuary temple between 1893 and 1907. This cache dates primarily from the reigns of Djedkare Isesi and Unas. One of the documents is a letter from Djedkare to the temple priests provisioning Neferirkare's funerary temple.

Mortuary complex

From the large size of his mortuary complex at Abusir, he was an important king, but since the Palermo stone fragments after his rule, little is actually known about his reign. The Pyramid of Neferirkare Kakai (burial place of the king) was initially designed as a 6-step pyramid 52 m high, but later it was extended to the form of a typical pyramid and it reached a height of 72 m. The mortuary complex is unfinished, and only part of the lower mortuary temple was completed before, it is supposed, the abandonment of the project.

Personality

Neferirkare's reign was unusual for the significant number of surviving contemporary records which describe him as a kind and gentle ruler. When Rawer, an elderly nobleman and royal courtier, was accidentally touched by the king's mace during a religious ceremony—a dangerous situation which could have caused this official's death or banishment from court since the Pharaoh was viewed as a living God in Old Kingdom mythology—Neferirkare quickly pardoned Rawer and requested that no harm should occur to the latter for the incident.[8] As Rawer gratefully states in an inscription from his Giza tomb:

| “ | Now the priest Rawer in his priestly robes was following the steps of the king in order to conduct the royal costume, when the sceptre in the king's hand struck the priest Rawer's foot. The king said, "You are safe". So the king said, and then, "It is the king's wish that he be perfectly safe, since I have not struck at him. For he is more worthy before the king than any man."[9] | ” |

Similarly, Neferirkare gave the Priest of Ptah Ptahshepses the unprecedented honor of kissing his feet.[10] Finally, when the Vizier Washptah suffered a stroke while attending court, the king quickly summoned the palace's chief doctors to treat his dying Vizier. When Weshptah died, Neferirkare was reportedly inconsolable and retired to his personal quarters to mourn the loss of his friend. The king then ordered the purification of Weshptah's body in his presence and ordered an ebony coffin made for the deceased Vizier. Weshptah was buried with special endowments and rituals courtesy of Neferirkare.[11] The records of the king's actions are inscribed in Weshptah's tomb itself and emphasize Neferirkare's humanity towards his subjects.

References

- ↑ Shaw, Ian, ed. (2000). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press. p. 480. ISBN 0-19-815034-2.

- ↑ Peter Clayton, Chronicle of the Pharaohs, Thames & Hudson Ltd, 1994. p.61

- ↑ I. E. S. Edwards, ed., The Cambridge Ancient History, part Two, ISBN 0-521-07791-5, p.183

- 1 2 Aidan Dodson & Dyan Hilton, The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt, Thames & Hudson (2004)

- ↑ El-Awady, T., Abusir XVI. The Pyramid Causeway. History and Decoration Program In The Old Kingdom, Charles University in Prague, Prague (2009), 246f., 170f. idem. in Art and Archaeology: ‘King Sahura with the precious trees from Punt in a unique scene!’, in Bárta, M. (ed.), Art and Archaeology of the Old Kingdom, Czech Institute of Egyptology, Prague (2005), pp. 37–44; idem. in Abusir and Saqqara 2005: ‘The royal family of Sahura: New evidence’, in Bárta, M., Coppens, F. & Krejčí, J. (eds.), Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2005, Czech Institute of Egyptology, Prague (2006), pp. 205–232.

- 1 2 New Archaeological Discoveries in the Abusir Pyramid Field - by Miroslav Verner: Sahure's Causeway (2007)

- ↑ Miroslav Verner, Archaeological Remarks on the 4th and 5th Dynasty Chronology, Archiv Orientální, Volume 69: 2001, p.393

- ↑ Erik Hornung, "The Pharaoh" in Sergio Donadoni's The Egyptians, University of Chicago Press, 1997, p.288

- ↑ Bill Manley, The Penguin Historical Atlas of Ancient Egypt, Penguin Books, 1996., p.28

- ↑ Miroslav Verner, The Pyramids, Grove Press. New York, 2001, p.269

- ↑ J. H. Breasted, Ancient Records of Egypt: Historical Documents from the Earliest Times to the Persian Conquest, University of Chicago Press: Part One, (1906) pp.243-249