Nicobar megapode

| Nicobar megapode | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Galliformes |

| Family: | Megapodiidae |

| Genus: | Megapodius |

| Species: | M. nicobariensis |

| Binomial name | |

| Megapodius nicobariensis Blyth, 1846 | |

| Subspecies | |

| |

| |

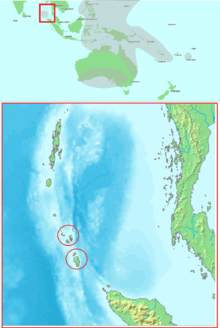

| Distribution of Nicobar megapode, grey area shows the distribution range of other megapodes | |

The Nicobar megapode or Nicobar scrubfowl (Megapodius nicobariensis) is a megapode found in some of the Nicobar Islands (India). Like other megapodes relatives, it builds a large mound nest with soil and vegetation, with the eggs hatched by the heat produced by decomposition. Newly hatched chicks climb out of the loose soil of the mound and being fully feathered are capable of flight. The Nicobar Islands are on the edge of the distribution of megapodes, well separated from the nearest ranges of other megapode species. Being restricted to small islands and threatened by hunting, the species is vulnerable to extinction. The 2004 tsunami is believed to have wiped out populations on some islands and reduced populations on several others.

Description

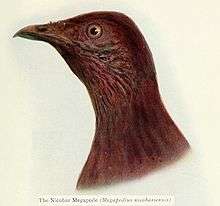

Megapodes are so named for their large feet and like others in the group, this species is fowl like with dark brown plumage, a short tail and large feet and claws. The tarsus is bare with the hind toe situated on the same level as the front toes unlike those of other Galliform birds, enabling them to grasp objects better than other game birds. The tarsus has broad flat strip like scales on the front. The tail is short with twelve feathers.[2] The head is more grey with a rufous crest and bare reddish facial skin. The males and females are very similar but the male is dark brown overall while the female has more grey on the underparts. Young birds have a fully feathered face and hatchlings are small quail-like with rufous barring on the wings and back. The nominate subspecies is paler than abbotti from the islands south of the Sombrero Channel.[3][4]

Taxonomy and systematics

This species was collected by Reverend Jean Pierre Barbe and described by Edward Blyth in 1846.[5] Some workers have considered the species to be subspecies of the dusky megapode (Megapodius freycinet).[4] The exact island from which the original type specimen came was not known and a later specimen from Trinkat Island, described as Megapodius trinkutensis is now considered to be indistinguishable from the nominate subspecies. In 1901, W L Abbott collected specimens from Little Nicobar which were described in 1919 by H C Oberholser as a new subspecies abbotti, distinguished by its darker brown plumage.[6]

Distribution and status

The species is found only in the Nicobar Islands. This range is so well separated from the main megapode distribution (especially of the genus Megapodius) that in 1911, it was suggested, on the basis that many megapodes were domesticated and transported by native islanders, that it may have been introduced into the Nicobar Islands.[7][8] There have been suggestions that the species may have formerly occurred in the Andaman Islands as there are some late 19th century reports of the species on Great Coco and Table Island.[9] The nominate subspecies is found on the islands north of the Sombrero Channel while abbotti is found south of it. It has been found on the islands of Tillanchong, Bompoka, Teressa, Camorta, Trinkat, Nancowry, Katchall, Meroe, Trax, Treis, Menchal, Little Nicobar, Kondul, Great Nicobar and Megapode Island.[10][11] The species may have occurred on Car Nicobar in the early 1900s.[12] A survey after the 2004 tsunami however indicated that the species had been extirpated on the islands of Trax and Megapode.[13] The eggs as well as adults are sought after by natives for food and birds may have been transported across islands.[14][15] The 19th century ornithologist A O Hume considered the taste of the meat as being between that of a "fat Norfolk turkey and a fat Norfolk pheasant".[16][17]

Behaviour and ecology

The Nicobar megapodes are secretive in their habits. During the day, they move around in thick jungle adjacent to the sea shore. In the dark, they venture out on the shore. They move in pairs or small groups. The group may consist of birds of various ages including just hatched ones. When disturbed, they prefer to escape by running but take to wings when pressed. The group keeps in touch with cackling calls.[18][19] Pairs indulge in duet calling and maintain territories. Many species in the genus are said to be monogamous, but the Nicobar megapode has been found to form temporary pair bonds.[20]

The Nicobar megapode has an omnivorous diet. They forage mainly by scratching and raking debris on the ground using their feet. A study in Great Nicobar found from an examination of their stomach that their food was mainly made up of the seeds of Macaranga peltata followed by insects, snails, crustaceans and reptiles. They also ingest grit to aid in digestion and have been observed to drink rainwater.[21]

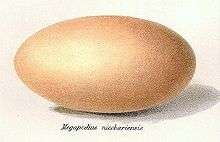

Like other megapodes in the genus, they build a large mound nest. The mounds are generally built close to the coast. These mounds are constructed with coral sand containing minute shells and plant materials, such as leaves, twigs, and other debris. Mounds are built on open grounds or against a fallen log or tree stump, or against a large living tree. Generally mounds are reused, by scraping the top layer of sand, piling up fresh vegetable matter and then raking up a new layer of sand. A mound may be shared by a pair and their progeny. New mounds are built either by digging a pit or piling up soil and plant materials against the stump or fallen log. The mound size varies considerably (less than 1 cu. m to more than 10 cu. m), though this does not have an effect on the hatching success. The eggs are elongate elliptical in shape and at a sixth of the weight of the bird, relatively large. Peak egg laying was observed from February to May. The eggs are pinkish without markings or gloss, and loses its colour with age.[18] The egg is laid on the mound and the parent digs a hole to bury it within and covers it up with plant material and soil. On an average, 4 to 5 eggs are laid in a mound but up to 10 have been noted, the eggs being in very different stages of development. A single mound may be used by more than one pair of birds.[20] Microbial activity is the primary source of heat within mounds for incubation. The incubation period is approximately 70–80 days varying based on the incubation temperature.[12][22]

The young birds hatch fully feathered, and as soon as the feathers dry up, can fly. They do not need any parental care and join the group immediately.[19] In the 1900s, eggs taken to Calcutta zoo hatched and the chicks, reared on a diet of termites, grew very tame.[16]

References

- ↑ BirdLife International (2012). "Megapodius nicobariensis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- ↑ Blanford, WT (1898). The fauna of British India. Birds. Volume 4. Taylor and Francis, London. pp. 147–148.

- ↑ Rasmussen PC & JC Anderton (2005). Birds of South Asia: The Ripley Guide. Volume 2. Smithsonian Institution & Lynx Edicions. p. 118.

- 1 2 Ali, S & S D Ripley (1980). Handbook of the birds of India and Pakistan. 2 (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 1–3. ISBN 0-19-562063-1.

- ↑ Blyth, E (1846). "Notices and descriptions of various new or little known species of birds". Jour. Asiatic Soc. Bengal. 15: 1–54.

- ↑ Oberholser, H (1919). "The races of the Nicobar Megapode, Megapodius nicobariensis Blyth". Proc. U.S. Nat. Mus. 55 (2278): 399–402. doi:10.5479/si.00963801.55-2278.399.

- ↑ Dekker, Rene W. R. J. (1989). "Predation and the Western Limits of Megapode Distribution (Megapodiidae; Aves)". Journal of Biogeography. 16 (4): 317–321. doi:10.2307/2845223. JSTOR 2845223.

- ↑ Lister, JJ (1911). "The distribution the avian genus Megapodius in the Pacific Islands". Proc. Zool. Soc. Lond.: 749–759.

- ↑ Ball V (1880). Jungle life in India. Thomas de la Rue & Co, London. p. 407.

- ↑ Collar, NJ; AV Andreev; S Chan; MJ Crosby; S Subramanya; JA Tobias, eds. (2001). Threatened Birds of Asia (PDF). BirdLife International. pp. 793–799.

- ↑ Sankaran, R (1995). "The distribution, status and conservation of the Nicobar Megapode Megapodius nicobariensis". Biol. Conserv. 72: 17–26. doi:10.1016/0006-3207(94)00056-V.

- 1 2 Kloss, C.B. (1903). In the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. John Murray, London.

- ↑ Sivakumar K (2010). "Impact of the 2004 tsunami on the Vulnerable Nicobar megapode Megapodius nicobariensis". Oryx. 44: 71–78. doi:10.1017/S0030605309990810.

- ↑ Woodford, CM (1888). "General remarks on the zoology of the Solomon Islands and notes on Brenchley's Megapode". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London: 248–250.

- ↑ Shufeldt, RW (1919). "Material for a study of the Megapodiidae". Emu. 19: 10–28. doi:10.1071/MU919010.

- 1 2 Finn, Frank (1911). The game birds of India and Asia. Thacker, Spink & Co, Calcutta. pp. 152–154.

- ↑ Ogilvie-Grant, WR (1897). A hand-book to the game-birds. Volume 2. Edward Lloyd, London. p. 165.

- 1 2 Oates, EW (1898). A manual of the Game birds of India. Part 1. A J Combridge, Bombay. pp. 384–388.

- 1 2 Baker, ECS (1924). Fauna of British India. Birds. 5 (2nd ed.). Taylor and Francis, London. pp. 436–439.

- 1 2 Sankaran, R. & Sivakumar, K. (1999). "Preliminary results of an ongoing study of the Nicobar megapode Megapodius nicobariensis Blyth". Zoologische Verhandelingen. 327: 75–90.

- ↑ Sivakumar, K. & Sankaran R. (2005). "The diet of the Nicobar Megapode (Megapodius nicobariensis) in Great Nicobar Island". J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 102 (1): 105–106.

- ↑ Sivakumar, K. & Sankaran R. (2003). "The incubation mound and hatching success of the Nicobar Megapode (Megapodius nicobariensis Blyth)". J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 100 (3): 375–386.

Other sources

- Sivakumar, K. (2000) A study on the breeding biology of the Nicobar megapode Megapodius nicobariensis. Ph. D. Thesis, Bharathiyar University, Coimbatore, India

- Sivakumar, K. (2007) The Nicobar megapode Status, ecology and conservation: Aftermath tsunami Wildlife Institute of India, Dehra Dun.